When an artist paints a landscape, seascape or cityscape he has to decide whether what he produces is a topographically accurate depiction of what he is looking at or an idealized version. He may consider adding or removing something or placing some feature in a different place to enhance the finished product. He may decide that such action would create a more agreeable balance. He is the artist and it is his choice. The one caveat of course is that if it is a commissioned piece he may have to discuss what he proposes to change with the person who is paying for the painting.

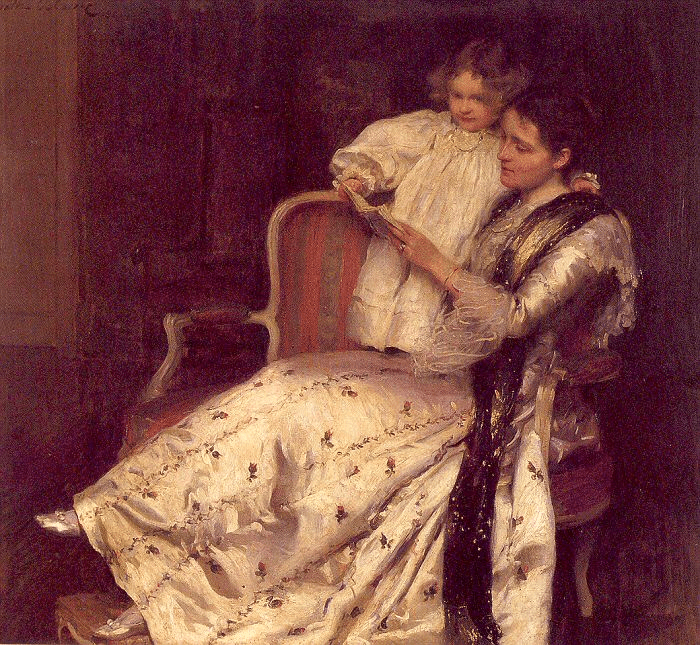

Portraiture is defined as the art of representing the physical or psychological likeness of a real or imaginary individual. Portraiture is also subject to the vagaries of idealism and verism. Idealistic portraiture often comes in the form of the backdrop and the accessories which surround the sitter and which, in some way, enrich the status of the sitter. Expensive furnishings, expensive tableware, expensive and fashionable clothes and jewellery worn by the sitter gives the viewer the feeling that the subject is prosperous and wealthy. Globes and books on a table near to the sitter can give the impression that they are learned and well-travelled. The figure of the sitter can be adjusted to make them look younger, more handsome or more beautiful.

One of the most famous idealised portraits was Botticelli’s depiction of Simonetta Vespucci, nicknamed la bella Simonetta. She was an Italian noblewoman from Genoa, the wife of Marco Vespucci of Florence and the cousin-in-law of Amerigo Vespucci. She was famous as the greatest beauty of her age in Northern Italy, and the model for many paintings by Botticelli and other Florentine painters. Speculation has it that the portrait of Simonetta is actually just an idealized version which emerged as the perfect beauty through Botticelli’s mind eye. The Italian Master achieved the flawless complexion of Simonetta by using a special mixture, terre verte – a green, earthy tone – to under paint, and afterward layered the flesh- like tones over it to create diverse shades of pink, yellow, and orange. Botticelli made use of fine lines and shapes to unobtrusively build up contrasts and fashion the depth and texture of the portrait. Apart from Botticelli, she also served other painters as an inspiration. She died young and childless at twenty-three. She presumably did not appear in public quite this perfectly styled. Her coiffure with beads, ribbons, feathers and artificial hairpieces would have been too elaborate and high-flown even by Florentine standards. Her outfit is much more likely to have been a nymph costume in the antique or classical-mythological style. This portrait is looked upon as the ideal of contemporary female beauty. Look at the way the artist has depicted her eyelashes and how she turns her body slightly towards us. It is the perfection of idealised beauty

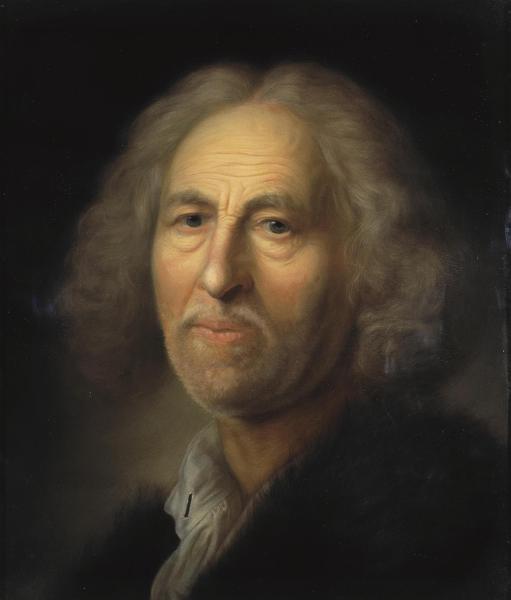

The opposite to idealism is verism. Verism is a term which dates back to the Roman Empire and is from the Roman Latin word verus meaning true and from Italian term verismo, meaning realism in its sense of gritty subject matter. In modern times the Italian term verismo, gives the sense of stark uncompromising subject matter. In portraiture verism is a form of realism in which a veristic portrait depicts a sitter with warts, wrinkles and all instead of a highly idealised depiction of smooth flawless skin. Veristic portraits do not attempt to idealize or beautify the subject; instead they represent all features of the individual, including wrinkles, imperfect proportions, balding, and blemishes of the skin

In this blog I am looking at the life of a great seventeenth century German portrait artist, who completed a number of veristic portraits. Today’s blog is all about Balthasar Denner, who will be remembered for his half-length and head-and-shoulders portraits of elderly men and women. Denner tended to focus attention on the face and if clothing was to be included in the depiction, he would leave that to other artists, including, in later years, his daughter, Catharina.

A good example of this collaboration can be seen in a painting he completed in 1724 entitled Three Children of Alderman Barthold Hinrich Brockes, on the back of which is an inscription stating that he painted the heads of the children, Jacob van Schuppen later in Vienna painted the bodies and costumes, and the background is from Franz de Paula Ferg. The flowers in the hands of the children were painted by Franz Werner Tamm.

Balthasar Denner was born on November 15th 1685 in Altona, now a suburb of Hamburg but, at the time Altona was part of the Danish kingdom and second only to Copenhagen in size. He was one of eight children but was the only son. His mother was Catharina Wiebe. His father was Jacob Denner, a Mennonite minister who was involved with the business of dyeing cloth. At the age of eight Balthasar was involved in an accident which resulted in him walking with a limp for the rest of his life. Following the accident, he was laid up in bed for a long period and to the pass the time he began to draw and started to copy the works of the Dutch painters, Abraham Bloemaert and Nicolaes Berchem whose works were very popular at that time.

Denner received his first artistic training from Frans van Amama, a Dutch painter. In 1696, at the age of eleven, Balthasar and his family left Altona and went to live in Danzig, where his father worked for a while as a Mennonite pastor. When he was thirteen years old Balthazar took up oil painting. The family returned to Altona in 1701 and Balthasar was put to work as a clerk for his uncle who was a prosperous merchant. Denner remained in the Hamburg suburb until 1707 at which time, aged twenty-two, he went to live in Berlin and that year became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. This state arts academy was established in 1696 in Berlin by prince-elector Frederick III and was the third oldest art academy in Europe. At the start of his artistic career Denner concentrated on painting miniatures which became very sought-after items.

In 1709, Balthasar Denner obtained his first significant commission – to paint the portraits of Christian August, the uncle and guardian of Karl Friedrich, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, and his sister Marie Elisabeth, the later Abbess of Quedlinburg. On completion of the portrait, Denner’s client was so captivated by the finished result that he invited him to Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig to paint other portraits, and in 1712 Denner completed a memorable group portrait which included twenty-one individuals from the Duke’s court. The group portrait is now housed in Schloss Rastede, near Oldenburg in Germany and it was this painting which greatly enhanced the reputation of Balthasar Denner as an exceptionally talented portrait painter.

During his stay in Berlin, he would frequently return to his home town of Altona. In 1712, in Hamburg, he married Esther de Winter and the couple went on to have six children, five daughters and a son. After the destruction of Altona in 1713, burnt to the ground by Swedish troops, during the Great Nordic War which had begun in 1700 between the forces of Sweden and the might of Russia and its allies, Norway and Denmark, Balthasar moved from Altona to Hamburg.

Denner travelled a great deal in the next ten years following up commissions from wealthy clients. In 1714 he made a trip to Amsterdam and later, in 1720 he visited the court in Wolfenbüttel and Hanover. Whilst in Hanover he became acquainted with many Englishmen who were living in the German city and it was through these friendships that he and his family were invited to come to London. His painting of an Old Woman circa 1720 received great acclaim. On his way to England he met the Dutch painter, Adriaen van der Werff, who the great art historian, Arnold Houbraken, considered was the greatest of the Dutch painters and such acclaim was the prevailing critical opinion throughout the 18th century. Van der Werff, on seeing Denner’s portrait, compared it to the Mona Lisa.

The work also caused great excitement in London and it was sent to Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor. Denner received 5875 guilders and in 1725 and was commissioned to paint an old man as a pendant piece for the same amount of money. Denner stayed in the English capital for seven years but eventually returned to Hamburg complaining that he could no longer endure the smog which beset London

In 1729 he was invited to visit the court in Blankenburg am Harz en Dresden and later travelled to Berlin. The wealthy and the European nobility all wanted to be painted by him and have their portrait hanging in their stately homes. Around 1740 he painted ten copies of the twelve-year-old Peter III (Russia) which were sent to all the European courts and one was sent to the court of Petersburg. In 1742 he the court of St Petersburg offered Denner a position as court painter with an immense salary but he declined the offer

In 1743 he painted Adolf Frederick, King of Sweden. Two years later, around 1745 he returned with his family to lived in his birthplace, Altona and it was here that three of his children died. It was a time of great sadness, and such was his grief that Denner, for a whole year, would never put brush to canvas.

Balthasar Denner died on April 14th 1749 aged 63, in Rostock. At the time of his death there were forty-six unfinished paintings in his Altona studio. Klara Garas the Hungarian art historian, and one-time Director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest described Denner’s portraiture:

“… ‘Denner’s genre figures and character heads depicting wrinkled old women and men were particularly popular and were admired for their detailed execution and meticulous accuracy. They ensured the artist international success and attracted especially high fees: Emperor Charles VI of Austria is believed to have sent 600 ducats from Vienna in payment for a typical head of a woman, an extraordinary sum at that time…”