The 16th century the art scene of Venice was dominated by three artists, Titian, Paolo Veronese, and Jacopo Tintoretto and it was these three painters who managed to tender for and win most of the public and religious commissions, which were on offer during that period. My featured painting today was one of Veronese’s most controversial paintings. It was intended to be a monumental work depicting the Last Supper but as you will now read that Veronese, three months after its completion, had to hastily change the title of the painting. The work, which is now entitled Feast at the House of Levi, is a massive work of art measuring 555cms x 1280cms (18’6″ x 42’6″) and was far too big to be included in the recent Veronese Exhibition at the National Gallery, London but I have been fortunate enough to stand in front of this amazing work a few years ago when I visited the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. It is a truly magnificent painting.

In 1573, Paolo Veronese, who was at the time forty-five years old, was awarded the commission to paint a depiction of the Last Supper for the rear wall of the refectory of the fourteenth century Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo, sometimes known as the pantheon of doges, as twenty-five of them have been buried there. It is one of the largest churches in the city of Venice. The building of this great church started around 1333 but was not completed until November 1430 as the construction was halted on many occasions due to the never-ending plagues that the city suffered during the 14th century. This painting by Veronese would replace Titian’s painting, The Last Supper, which had been lost in a fire in 1571. According to the writing on the base of the pillars, to the left and right in the foreground of the painting, the work was completed by Veronese on April 20th 1573. When I looked at some of the Veronese paintings at the National Gallery exhibition in my previous two blogs, I talked about the artist’s penchant for combining secular depictions in some of his religious works, such as his painting, Supper at Emmaus, and in today’s painting we can see that this theme was once again adopted, much to the horror of the Catholic Church. So let us look in more detail at this immensely impressive work.

In the painting we see a monumental triple-arch background through which one can see more magnificent buildings of Venice cityscape. This was more than likely inspired by buildings designed by the great Italian architects of the time, Andrea Palladio and Jacopo Sansovino, who designed many of the Venetian buildings in the sixteenth century. In the foreground of the painting and on either side of the depiction of Christ at the Last Supper, we witness a scene of great merriment, with jesters and blackamoors, along with the nobility of Venice enjoying their own sumptuous feast. Veronese has simply combined the Last Supper with Christ and his Apostles with a typical Venetian dinner party. The first thing that strikes you about this work is the large number of figures that have been included in the work, one could say, almost crammed into the work and because the work is somewhat cluttered by human beings, the depiction of Christ at the Last Supper seems almost lost in the melee and this is part of the reason why it did not find favour with the Church. One realises that the artist must have derived great joy from including all these various figures, all doing different things and for him this maybe what the painting was about and that the Last Supper was just a bi-product of the work. Maybe we can glean an understanding of Veronese’s modus operandi by his description of his work as an artist when he described what he did, saying:

“I paint and compose figures”

The Church’s displeasure of the completed work was not just that the depiction of the Last Supper, in the central background of the painting, seems almost to play a secondary and minor role in the work; it was that they were horrified by some of the numerous other characters who populated the work. Veronese’s inclusion of this assortment of characters into such a famous religious scene was looked upon by the Church as being irreverent, bordering on blasphemous. One has to remember that this period marked the beginning of the Counter Reformation which was the Catholic Church’s attempt to strongly and vociferously oppose the Protestant Reformation and to move towards a re-definition of good Catholic values. The Church was very wary about anything which could be perceived as mocking the Church and its values. This counter-reformation movement attempted to elevate the moral and educational standards of the clergy and by so doing enable it to win back areas endangered by Protestantism. So when Veronese added a plethora of people, some of whom seemed to be drunk, as well as dogs, a cat, midgets, and Huns to the depiction of Christ at the Last Supper at the house of Simon, the elders of the Church were horrified. Veronese was summoned to appear before the Inquisition on July 18th 1573 which was sitting in the Chapel of S. Teodoro.

One of the first questions posed by his inquisitors was whether he knew why he had been summoned before them. Veronese replied:

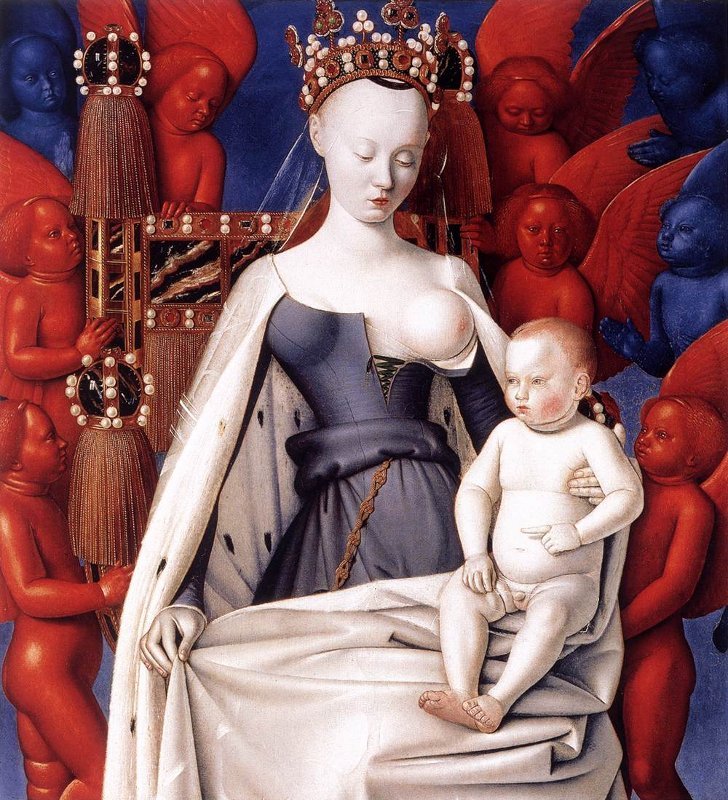

“…I fancy that it concerns what was said to me by the reverend fathers, or rather by the prior of the monastery of San Giovanni e Paolo, whose name I did not know, but who informed me that he had been here, and that your Most Illustrious Lordships had ordered him to cause to be placed in the picture a Magdalene instead of the dog; and I answered him that very readily I would do all that was needful for my reputation and for the honour of the picture; but that I did not understand what this figure of the Magdalene could be doing here…”

The inquisitors were not pacified by his answer and began to question him in more detail. They asked him why he had included two German soldiers seen on the stairway, standing guard bearing halberds, in the right foreground. One has to remember it was the German Martin Luther, who initiated the Protestan Reformation fifty-five years earlier and it was he who had been a thorn in the side of the Catholic Church, constantly criticising the ways of the Catholic clergy and the Catholic doctrine. The Inquisition wanted to know why such frivolous things as a dwarf with a parrot on his arm, a dog which sits before Christ’s table staring at the cat which has appeared under the tablecloth had been included in a deeply religious scene. Veronese had all the answers ready. As far as the German soldiers he answered:

“…We painters use the same license as poets and madmen, and I represented those halberdiers, the one drinking, the other eating at the foot of the stairs, but both ready to do their duty, because it seemed to me suitable and possible that the master of the house, who as I have been told was rich and magnificent, would have such servants…”

The inclusion of the two Germans in the painting was considered by the inquisitors an even greater sin than the other inclusions the inquisitors questioned Veronese again as to their inclusion.

“…Do you not know that in Germany and other countries infested by heresy, it is habitual, by means of pictures full of absurdities, to vilify and turn to ridicule the things of the Holy Catholic Church, in order to teach false doctrine to ignorant people who have no common sense?…”

Veronese realised he was now on dangerous ground but skilfully replied:

“… I agree that it is wrong, but I repeat what I have said, that it is my duty to follow the examples given me by my masters…”

Veronese was probably now becoming a little fearful at the way the questioning was going and so decided to go down the line of – if you think I have blasphemed with my painting, what about the much beloved Michelangelo’s work in the Vatican. Veronese expanded:

“…In Rome, in the Pope’s Chapel, Michelangelo has represented Our Lord, His Mother, St. John, St. Peter, and the celestial court; and he has represented all these personages nude, including the Virgin Mary, and in various attitudes not inspired by the most profound religious feeling…”

The Inquisitors however would not criticise Michelangelo’s work, merely saying that in the depiction of the Last Judgement, which Veronese was referring to, it was only natural that the people were without clothes and that the work had been inspired by the Holy Spirit. They then turned on Veronese stating that there was no indication that his work had been so inspired by the Holy Spirit and that he needed to make some changes to it. They then compared Michelangelo’s work with his and commented:

“…There are neither buffoons, dogs, weapons, nor other absurdities. Do you think, therefore, according to this or that view, that you did well in so painting your picture, and will you try to prove that it is a good and decent thing?..”

A little trickier was the question as to why he would include a jester with a parrot on his wrist in such a “sacred” work. However, he was not to be browbeaten and simply answered:

“…He is there as an ornament, as it is usual to insert such figures…”

Veronese did however agree with his inquisitors that there was only Christ and his twelve apostle present at the table during the Last Supper but forwarded the reason for the inclusion of so many characters. He said that the painting was to be so large that he had to fill the space with something, saying:

“…when I have some space left over in a picture I adorn it with figures of my own invention…”

The inquisitors countered Veronese’s argument by asking him whether he thought he had the right to mock the Last Supper by including irreligious figures, such as buffoons, dwarves, a dog, a cat and worst of all Germans. Veronese replied:

“…No, but I was commissioned to adorn it as I thought proper; now it is very large and can contain many figures…”

The way in which Veronese had depicted the Last Supper seen in the central background was also criticised by the Inquisition. This was not similar to the portrayal of Last Supper à la Leonardo. Veronese’s table scene was more of an everyday festive scene and this was not lost on the inquisitors who wanted to know what was going on at the supper table. They started by questioning Veronese as to who was sitting down with Christ. He answered:

“…The twelve apostles…”

They then questioned what the person, Saint Peter, on the right hand of Christ was doing. The artist responded:

“… He is carving the lamb in order to pass it to the other part of the table and Christ holds a plate to see what Saint Peter will give him…”

On questioning what a third person at the table was doing he merely commented:

“…. He is picking his teeth with a fork…”

In a desperate final attempt to justify the inclusion of all the extra people, both normal and strange, he pointed out that such elements that displeased the Inquisition, such as the dog, the dwarf, the blackamoors, the man with the nosebleed, who is seen holding a handkerchief at the left of the picture, were all in the foreground or the sides of the painting, and did not, in any way, form an incursion into the religious depiction of Christ at supper at the centre of the work.

With a terrible sense of foreboding the questions came to an end and Veronese awaited his fate. So, it was much to his surprise that at the end of the interrogation Veronese was told that he was a free man. However as the Inquisition could not accept his argument for adding what they termed “anti-conformist elements” he was given three months to correct the painting at his own expense. They required him to paint out the dog, and replace it with the Magdalene. He was also to expunge the German soldiers and it was all to be done within three months. Paolo Veronese, who had feared torture and even death because of his heretical depiction of the Last Supper, couldn’t believe his luck. So how had he managed to escape the full force of the Inquisition? Maybe the answer lay in the fact that the Inquisition had much reduced powers in Venice and the inquisitors knew that they could only threaten and not use the brutal methods of torture that was taking place in other countries such as Spain and Italy. They simply wanted to frighten Veronese in the hope that he would think twice before he again combined secularity with religious scenes. The Inquisition in Venice was also fully aware that every judgement they made was scrutinised by the Venetian Senate, who were ready to drastically curtail their powers, if they dared to take away the liberty of a Venetian subject and, of course, Paolo Veronese was one such subject.

Veronese never made any of the major changes to his painting that the Inquisition had demanded, but in deference to Ecclesiastical sensibilities and not wishing to push his luck, he added the inscription across the top of the pillars at the head of the staircases, the ones which also showed the date of completion. The inscription read:

Fecit D.Covi Magnum Levi Luca Cap. V

This was in reference to a passage in Luke’s gospel of the New Testament (Luke 5: 27-29):

“…After this, Jesus went out and saw a tax collector by the name of Levi sitting at his tax booth. “Follow me,” Jesus said to him, and Levi got up, left everything and followed him. Then Levi held a great banquet for Jesus at his house, and a large crowd of tax collectors and others were eating with them…”

He then merely changed the title of the work from The Last Supper to Feast at the House of Levi and by doing so was able to retain the dog and removed the need for it to be replaced by a repentant Magdalene prostrating herself on the floor before Christ. Veronese’s decision not to make the changes pleased both the friars who loved the painting, and for the majority of Venetians who resented Rome’s inquisition. The painting remained in the refectory of the Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo until Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops marched into Venice in 1797 and he ordered it be taken back to Paris. It was returned to Venice a decade later and remained in the church until 1815, at which time it was acquired by the Accademia Galleries in Venice, its current home.

One final thought as to why Veronese would add so many people into a religious scene. A decade earlier, in 1563, he had completed a similar monumental religious commission for the monks, entitled the Wedding at Cana, which now hangs in the Louvre. It is interesting to note that it was the monks who had asked him to squeeze as many figures into their painting, as possible. This was however at a time when the Inquisition and the upholding of Counter-Reformation ideals had yet to reach Venice.