My featured artist today is the 17th century Italian Baroque painter Salvator Rosa. He was born in 1615 in the small hill town of Arenella above the outskirts of Naples. His father Vito Antonio was a land surveyor and had great ambitions for his son wanting him to become either a lawyer or take holy orders in the church and become a priest. With this in mind he decided that his son should be afforded the best education and had him enter the convent of the Somaschi Fathers, a holy order of priests and brothers. As we have seen in many biographies of artists, what the parents want for their children often differs from what the children themselves want and so it was the case for Salvator Rosa. During his studies he had developed a love of art and with the support of his maternal uncle, Paolo Greco, he secretly began to learn to paint. Rosa began his artistic training in Naples, under the tutelage of his future brother-in-law, Francesco Francanzano, who had trained under the influential Spanish painter, Jusepe de Ribera. It is also believed that after this initial training, Rosa trained with the Naples painter, Aniello Falcone, who was also at one time apprenticed to Ribera. Rosa greatly admired the works of Ribera and was influenced by them.

His father died when he was seventeen years old and, as he had been the breadwinner to Rosa’s large family, his mother struggled to feed her children let alone financially support her son Salvator with his artistic ambitions. After his father’s death, Salvator Rosa continued to work as an apprentice with Falcone until 1634 when he relocated to Rome where he stayed for two years before returning home.

In 1638, aged 23 he went back to Rome where he was given accommodation by the Bishop of Viterbo, Francesco Brancaccio who treated him as his protégé and received commissions from the Catholic Church. It was whilst in Rome that Rosa further developed his multi-talented skills, not just as an artist but as a musician, a writer and a comic actor. He founded a company of actors in which he regularly participated. He wrote and often acted in his own satirical plays, often political in nature and often lampooned the wealthy and powerful, and it was his devilish satire which gained him the reputation of a rebel, pitting himself against these influential people. However his viperish-tongued satires made him some powerful enemies including Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the famous and powerful architect and who was at that time, the most powerful artist in Rome. He, like Rosa, was also an amateur playwright and it was during the Carnival in 1639 that Rosa ridiculed Bernini’s plays and his stature as a playwright. Eventually Rosa had made too many enemies in the Italian capital and decided it was just too dangerous to remain there.

From Rome he travelled to Florence where he was to remain for the next eight years. One of his most influential Florentine patrons was Cardinal Giancarlo de’ Medici, himself a great lover and supporter of the Arts. Rosa worked for the Cardinal at his palace but was still allowed the freedom to paint his own landscapes and would go off and spend the summers in the Tuscan countryside around Monterufoli and Barbiano. It was whilst living in Florence that Rosa did some work for Giovanni Carlo who was at the centre of the literary and theatrical life of Florence and Rosa soon became part of Carlo’s circle of friends. Rosa used his own house as a meeting place for local writers, musicians and artists and it became known as the Accademia dei Percossi, or Academy of the Stricken.

He left Florence in 1646 being unhappy with the ever increasing restrictions put on him and his artistic and literary work by the Medici court He went first back to Naples where he remained for three years before returning to Rome in 1649 where he believed his writings and paintings would win him even greater fame. One of the problems Salvator Rosa had was his ever tempestuous relationship with his patrons and their demands. He often refused to paint on commission or to agree a price beforehand. He rejected interference from his patrons in his choice of subject. In Francis Haskell’s book entitled, Patrons and Painters: Study in the Relations Between Italian Art and Society in the Age of the Baroque, he quotes from a letter Rosa wrote to one of his patrons, Antonio Ruffo, explaining his thoughts on his art and commissions:

“…I do not paint to enrich myself but purely for my own satisfaction. I must allow myself to be carried away by the transports of enthusiasm and use my brushes only when I feel myself rapt…”

The 17th century Florentine art historian Filippo Baldinucci could not believe Rosa’s attitude to his patrons and wrote:

“…I can find few, in fact, I cannot find any, artists either before or after him or among his contemporaries, who can be said to have maintained the status of art as high as he did… No one could ever make him agree a fixed price before a picture was finished and he used to give a very interesting reason for this: he could not instruct his brush to produce paintings worth a particular sum but, when they were completed, he would appraise them on their merits and would then leave it to his friend’s judgement to take them or leave them….”

In his later years he spent much time on satirical portraiture, history paintings and works of art featuring tales from mythology. In 1672 he contracted dropsy and died six months later. Whilst on his deathbed he married Lucrezia, his mistress of thirty years, who had borne him two sons. He died in March 1673 just a few months short of his fifty-eighth birthday. After his father’s death forty years earlier Rosa had struggled financially but at the time of his death he had accumulated a moderate fortune.

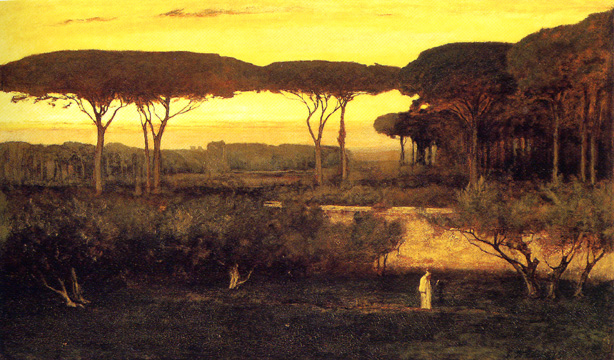

Landscape painting had been regarded as a relatively lesser genre of painting in Italy at the time. But two French artists based in Rome, Claude Lorraine, who Rosa had befriended, and Nicholas Poussin, had done much to raise its status by setting scenes drawn from classical myth or biblical legend in grand Arcadian landscapes inspired by the nearby countryside. Rosa continued their tradition but with one subtle difference. His landscape scenes depicted scenes of stormy desolation rather than calm pastoral beauty scenes of Claude and Poussin. For My Daily Art Display today I am going to look at a painting by Salvator Rosa, which is a landscape but based on Roman mythology and Ovid’s book Metamorphoses. It is the story of Apollo (often known as Phoebus) and the Cumaean Sibyl. Cumae, which was the location of Italy’s earliest Greek colony, is on the Gulf of Gaeta near Naples and this location was probably known to Rosa. The basis of the painting harks back to a conversation Aeneas had with the Cumaean Sibyl, who was a guide to the underworld of Hades, the entrance to which was the volcanic crater of Avernus. Aeneas wanted to enter the underworld in order to visit his dead father Anchises. Aeneas, with the help of his guide, the Cumaean Sibyl, found the aged ghost of his father. It was at this time that the Sibyl recounted the story of her barter with the god Apollo, how she reneged on her promise and why she had become old and haggard:

“…“I am no goddess,” she replied, “nor is it well to honour any mortal head with tribute of the holy frankincense. And, that you may not err through ignorance, I tell you life eternal without end was offered to me, if I would but yield virginity to Phoebus for his love. And, while he hoped for this and in desire offered to bribe me for my virtue, first with gifts, he said, ‘Maiden of Cumae choose whatever you may wish, and you shall gain all that you wish.’ I pointed to a heap of dust collected there, and foolishly replied, `As many birthdays must be given to me as there are particles of sand.’ For I forgot to wish them days of changeless youth. He gave long life and offered youth besides, if I would grant his wish. This I refused, I live unwedded still. My happier time has fled away, now comes with tottering step infirm old age, which I shall long endure…”

Her mistake had been not only to ask Apollo for eternal life but also to ask for everlasting youth and beauty. She aged over time. Her body grew smaller with age and eventually was kept in an ampulla, a small nearly globular flask or bottle, with two handles. Eventually only her voice was left.

The painting, entitled River Landscape with Apollo and the Cumaean Sibyl, depicting the meeting of the Cumaean Sibyl and Apollo, was painted by Salvator Rosa around 1655. This is one of his finest works and highlights his ability as a landscape painter. It is a desolate landscape scene. Before us we have an isolated inlet of the sea, surrounded by towering cliffs of rough and rugged stone. On the right hand side of the painting we have a dark crag which towers against a stormy summer sunset. From this jagged rock there are spindly trees sprouting from it at strange angles. In the foreground of the painting we see the god Apollo, seated on a tree stump with his lyre at his side, propositioning the beautiful Cumaean Sibyl, the turbaned woman who stands before him. His hand is raised almost as if he is blessing the woman but it is his demonstrative act of granting her wish that she might live for as many years as there are grains of dust in the earth she holds out to him in her hand. In return for the granting of her wish she would become his lover. The Sibyl having been granted her wish, changes her mind, and refuses to surrender to Apollo’s advances. Apollo cannot take back what he had given the young woman, but he was still able to punish the fickle girl, for, in devising her wish, she forgot to ask for eternal youth, and by refusing to grant her this he condemned her to grow older and older until at last she wasted away and only her voice was left.

The scene before us, depicted by Rosa, is purely imaginary, Rosa has included the cavern from which the Sibyl uttered her famous prophecies and which still exists in the dark, rocky area at the top right of the picture. In the background we can see the inaccessible citadel perched high on a cliff. The other characters we see in the scene are the nine muses, the goddesses of creative inspiration who were the handmaidens of Apollo. The painting is illuminated by the last rays of the setting sun light which light up the stormy sky in the distance. Look at how Rosa has managed to portray an aura of an ominous premonition. The dramatic use of dark tones and chiaroscuro adds a feeling of foreboding about the scene. The way he has depicted the wild landscape of bare rocks, splintered trees and a threatening stormy sky goes hand in hand with the story of retribution about to be dealt to the Cumaen Sibyl by Apollo for reneging on her promise to him.

Notwithstanding the darkness of the scene, it is still a beautiful landscape painting. It is currently housed at the Wallace Collection, London.