Today I am returning to the nineteenth century French academicism painter and sculptor Jean-Léon Gérôme, looking at his early life and featuring one of his works. I had previously featured this artist in My Daily Art Display of February 10th 2011 when I talked about his painting entitled A Roman Slave Market.

Jean-Léon Gérôme was born in 1824, in Vesoul; a small town close to the city of Besançon and near to the French-Swiss border. He was the eldest son of Pierre Gérôme, who was a goldsmith by trade, and his wife Claude Françoise Mélanie Vuillemot, a daughter of a merchant. He initially attended school locally in Vesoul where he was looked upon as a star pupil and attained a good deal of academic success culminating in being awarded first prize in chemistry, and an honourable mention in physics. From the age of nine he took drawing lessons under the tutelage of Claude-Basile Cariage and when he was fourteen years of age he received formal art tuition and was viewed as a great up-and-coming talent and he received a prize from the school for one of his oil paintings. At the age of sixteen, with his school days behind him, he set out for Paris with a letter of introduction to the French painter Paul Delaroche who at this time was at the height of his fame. Delaroche’s artistic style was a blend of the academic Neo-classical school and the dramatic subject matter favoured by the Romantics. This combination was to become known as the historical genre painting style. Gérôme was to be greatly influenced by the paintings and the tuition he received from Delaroche.

In 1845, after three years of studying under Delaroche and having just returned to Paris after a visit to his home in Vesoul, Gérôme discovered that Delaroche had closed his studio. Delaroche had just suffered the loss of his wife, Louise, whom he deeply loved and whom he had depicted in many of his paintings. Gérôme discovered him to be in the depths of depression following the death of his wife and was about to close his atelier and journey to Italy. Gérôme asked if he could accompany him. Delaroche agreed and the two of them along with a couple of other of Delaroche’s students, one of which was the English painter Eyre Crowe, set off on their painting trip.

Gérôme stayed in Italy and visited Naples where he viewed the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum which were to become the foundation for his gladiatorial depictions. His sojourn in Italy was cut short in 1844 when he contracted typhoid fever and he had to return home to Versoul where his mother nursed him back to health. Later that year, fully recovered, he returned to Paris and entered the atelier of the Swiss painter and teacher Charles Gleyre. Gleyre was to guide many young aspiring artists who would become famous household names, such as Monet, Renoir, Bazille and Whistler. From the studio of Gleyre, Gérôme went on to attend the École des Beaux-Arts.

Meanwhile, Delaroche, who had remained in Rome, returned to Paris to work on an important commission. Delaroche offered Gérôme a position as his assistant on the commission and so Gérôme left Gleyre’s studio to work with his former master. He remained as Delaroche’s assistant for just on a year. Whilst working alongside Delaroche, he was encouraged to prepare paintings for the Salon exhibitions and within a short time, his talent as an artist was recognised and he was commissioned to paint a reproduction for the Queen. This was to be the start of many official and lucrative commissions. In 1846 Jean-Léon Gérôme began to work on one of his most famous paintings – Young Greeks Attending a Cock Fight. Gérôme had just suffered the setback at the École des Beaux Arts of not achieving his main aim that of winning Prix de Rome prize, which would have given him a scholarship to travel to and study in Rome. He was probably questioning his own ability and was somewhat hesitant to submit his painting to the Salon jurists, but on Delaroche’s insistence, he did and it was accepted into the 1847 Salon and hailed a great success. One of those to take a liking to his work was the art critic and poet, Théophile Gautier, who would later support Gérôme throughout most of his career. Gautier’s commendation of The Cock Fight made Gérôme famous and his artistic career was well and truly launched.

Gérôme travelled extensively visiting Turkey in 1855 to make studies for a large official commission, and two years later journeyed to Egypt in preparation for the Salon of 1857 in which his first Egyptian genre paintings were shown. In the 1860’s he returned to Egypt and also visited Judea, Syria and the Holy Places. Gérôme was fascinated with the Near East and many of his subsequent works highlighted the Near East culture and traditions and it was to mark the start of his career as an Orientalist or a peintre ethnographique.

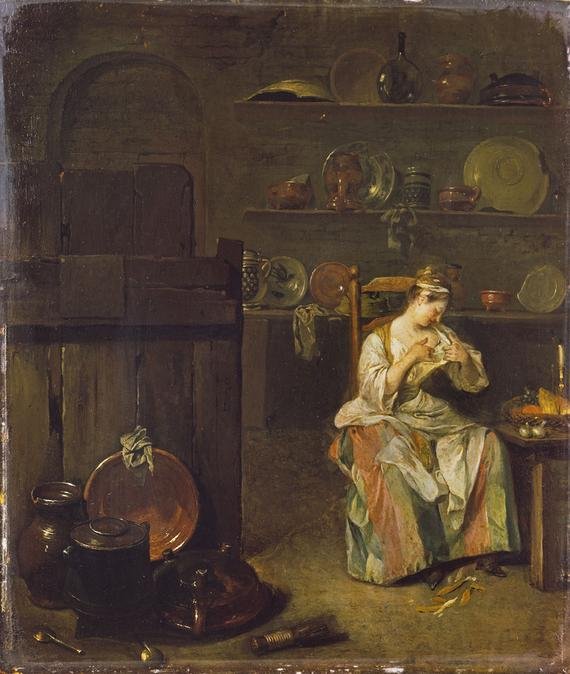

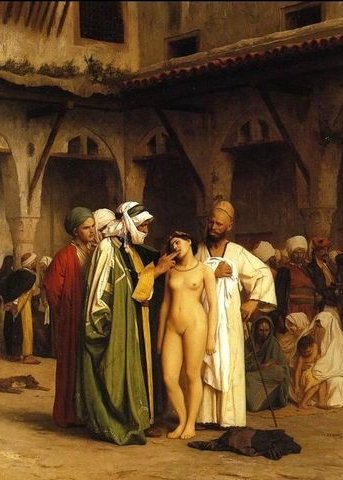

The painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme which I am featuring today was completed by him in 1866 and is entitled The Slave Market. It is without doubt one of Gérôme’s most provocative works. The scene is set in a market place in a Near East country, more than likely, Egypt. The idea for this painting and others featuring the slave market probably came to Gérôme during his Near East travels, when slavery was still practiced. However the open air slave market as shown in this painting did not exist in the mid-nineteenth century and so this should be viewed as an idealised depiction. The artist has put a great deal of effort into details of the costumes worn by the traders as well as the way in which he has carefully depicted, in detail, the architecture of the surrounding buildings. In the centre of the painting we see a nude woman who is being offered up as a slave and is surrounded by a group of prospective buyers. One of these men, dressed in a gold and green covered cloak, examines the “goods” on offer. His left hand holds the back of the woman’s head whilst the fingers of his right hand are forced into her mouth so he could better examine her teeth. Behind the woman stands the seller and from the smile on his face he seems assured that he is about to be paid handsomely for the woman. There can be no doubt that prospective buyers of this painting were not totally absorbed by the way the artist depicted the clothes worn by the prospective buyers or with the architecture of the building in the background. They were sold on the erotic nature of the painting. Viewers were able to be vociferous in their condemnation of the slave trade whilst enjoying the sight of the female body.

The painting was acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark in 1930 and is part of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts collection but is currently (until September 23rd) on view at the Royal Academy, London.