The early childhood and teenage years of Cecilia (Leilie) Beaux were challenging. She and her elder sister Etta lived with their maternal grandmother Cecilia Kent Leavitt and their maiden aunt Eliza. Leilie and Etta were completely different in character. Etta was the more placid and was happy to accept traditional domestic life and probably modelled herself on her grandmother who had nurtured her own eight children. Leilie, on the other hand, was both stormy and impassioned and hankered for her independence and believed that financial security would achieve that status. She would, like her late mother and aunt, Eliza, go out to work and earn money. Leilie was a perfectionist and suffered like all perfectionists tend to do. In her personal diary which she started at the age of fourteen, she wrote:

“…It seems to me that I haven’t progressed at all. I do believe that it is harder for some people to be good than others, a great deal harder. Some people seem to be good naturally like Etta…but as for poor me why I’m nothing absolutely nothing, able only to do wrong. Sometimes it seems to me as if I were tied in a spiritual way to a string of a certain length. I get on very well at first and feel so free and happy, feel as if I really was getting better, when suddenly I come to the end of my string, and am thrown back to the old place again…”

Leilie was often rebellious as a teenager, frustrated with her life and often aspiring to do something different. In her autobiography she remembered that in her teenage years she wrote a poem expressing her exasperation:

“…Lost hope, lost courage, lost ambition,

What’s left but shams of these to hide my true condition?

Feigned peace and joy, feigned happy effort,

False tongue, proclaiming, “Art’s my comfort.”

Nought’s left but bones, and stones and duty that’s not pleasure,

But grinding, ceaseless toil, whose end’s the measure

Of the short web of life the Fates have spun me.

What’s this… I’ve uttered words of treason.

What’s lost? My time, my daylight, and my reason…”

Leilie also suffered mentally from the departure of her father from the family home. Sadly, she blamed herself for his departure, as her mother had died giving birth to her. She began to make excuses for him abandoning his daughters. Despite his untimely and devastating departure she still managed to put him on a pedestal, someone to be almost adored.

Leilie was brought up in a family environment where music was an essential part of life. Her aunt Eliza was a highly talented musician and earned money for the family by giving music lessons. The family owned a Chickering grand piano and there would be frequent family recitals in the evenings with performances given by Eliza and William Beadle, Emily’s husband, who also acted as organist at the local Presbyterian church the family attended. When Leilie was eleven years old, she learnt to play the piano but never reached a level of accomplishment which satisfied her and so, as a perfectionist, she gave it up.

Henry Sturgis Drinker, was Cecilia Beaux’s brother-in-law (Etta’s Leavitt’s husband). He was a railroad executive and president of Lehigh University in Pennsylvania.

Up to the age of fourteen Etta and Leilie were home-tutored, mainly because of the high cost of formal schooling. Leilie’s early interest focused on literature and poetry and at one time she believed she would like to become a writer. William Biddle’s arrival on the scene as Emily Leavitt’s husband meant that the Leavitt’s finances improved, so much so, that it was decided that Etta and Leilie could afford to receive formal education at Misses Lymans’ School. It was an all-female school run by Catherine and Charlotte Lyman. This was the first time the two girls were able to absorb life outside the family. Leilie began to sketch and was pleased with her efforts. In her autobiography, Background with Figures, she wrote:

“…Long before it was discovered that I had more proficiency with a pencil than I had on the piano, I accompanied my aunts on visits to what picture galleries and special exhibitions there were…”

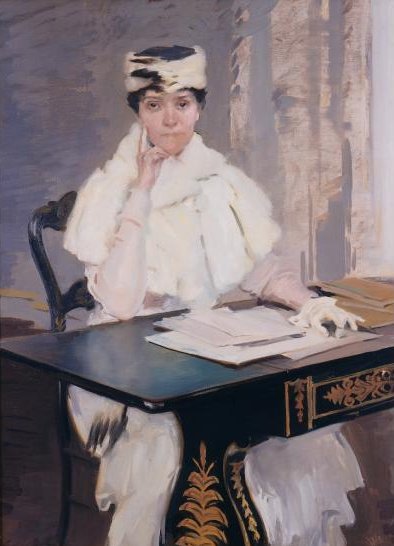

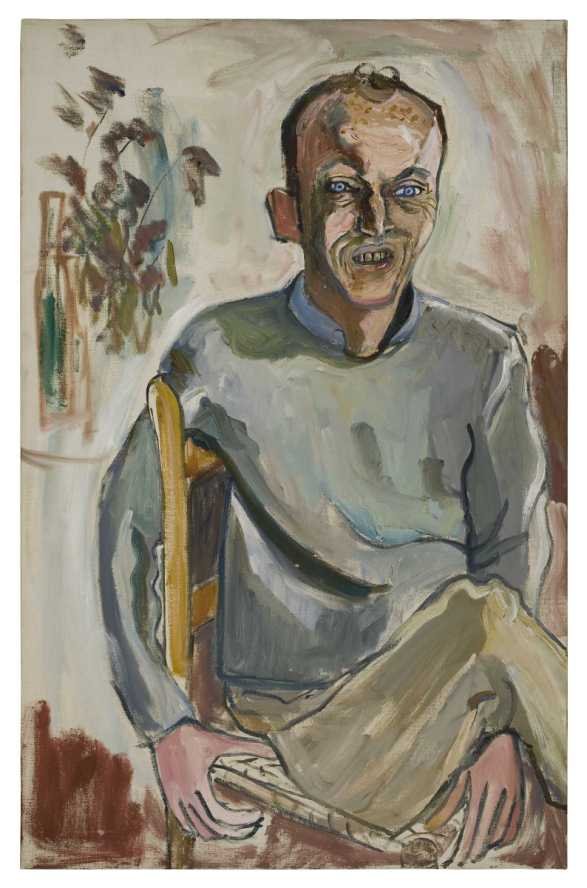

The portrait depicts the America author Henry James during his final trip to the United States, when he was recovering from a nervous breakdown and the death of his brother, William.

Leilie began to develop and interest in the Arts and her aunts and uncles would take her to various art galleries to encourage her. It was during the 1870’s that there was a sudden desire of wealthy Americans to buy works of art especially by French painters. It was a status symbol for these wealthy households to have works by the emerging French masters hanging on the walls so that they would impress visiting dinner guests. One such person, a wealthy and successful businessman, was Henry C. Gibson, an art collector, banker, real estate developer, and distiller. His Philadelphia house on Walnut Street housed many works of art and Leilie’s uncle was fortunate to receive an invite to view the works of art and he took Leilie with him. They must have re-visited the house on several occasions for she wrote in her autobiography:

“…Very few of the pictures were large, and all could be easily seen. Of course, I knew nothing of these virtues of presentation; I knew nothing but my own happiness. I must have been taken several times to the gallery, for I had my favorites and was unembarrassed by the difference of schools…”

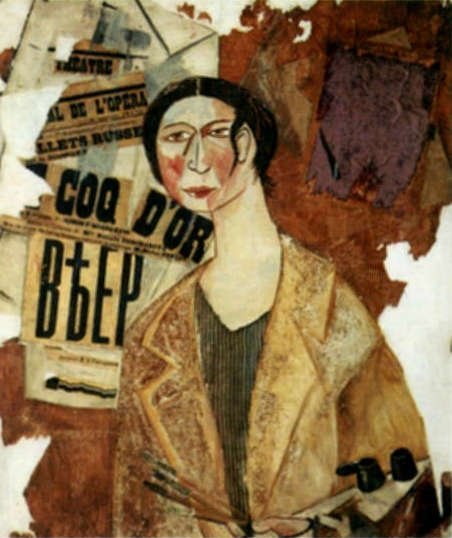

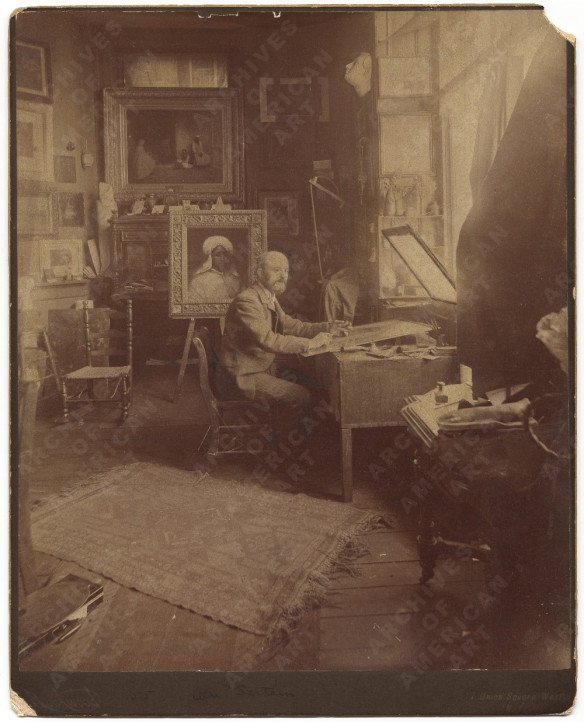

Her family decided that Leilie should pursue her interest in drawing and painting and needed to find someone who could nurture Leilie’s talent. The person chosen to guide Leilie was the talented artist, and painter of historical and biblical scenes, thirty-one-year-old Catherine Ann Drinker, who had a local studio. Coincidently, she would later become Etta’s sister-in-law in 1879 when Etta married her brother, Henry Sturgess Drinker. In 1871, sixteen-years-old Leilie remembered her first visit to Catherine Drinker’s Philadelphia studio which was at the top of an old house at Fifth and Walnut Streets on Independence Square. In her autobiography she wrote:

“…I am glad that the studio was typical, traditional, and not to be confused with any ordinary or domestic scene, for it was the first studio I ever entered. On its threshold, everyday existence dropped completely out of sight and memory. What windows there were, were covered with hangings, nondescript, as they were under the shadow of the skylight, which was upright, like a broad high window, and without glare. There was a vast sweeping curtain which partly shut off one side of the room, and this, with other dark corners, contributed to its mystery and suggestiveness. The place had long been a studio, and bore the signs of this in big, partly obliterated figures, outlines, drawn in chalk, upon its dusky wall, opposite the light. Miss Drinker had spent her early life in China, whence her family had brought many examples of Chinese art and furniture. The faded gold of a large seated Buddha gleamed from a dark corner. There was a lay figure, which was draped for a while in the rich robes that Miss Drinker had used for her ‘Daniel…”

In 1880, Catherine Drinker won the prestigious Mary Smith Prize for her painting Old Fashioned Music. This prize was awarded to women artists by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The award recognized the best work by a Philadelphia woman artist at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts annual exhibition — a work that showed “the most originality of subject, beauty of design and drawing, and finesse of colour and skill of execution”.

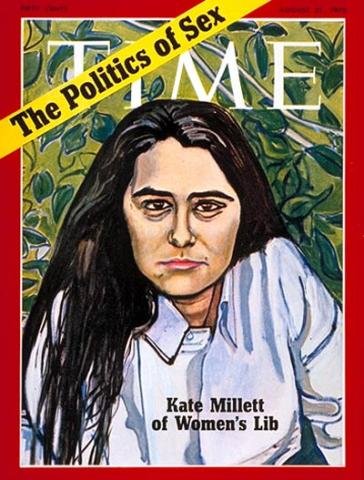

Many of Cecilia Beaux’s portraits were of New Englanders, including this elegant image of Charles Sumner Bird and his sister Edith.

The Bird family had made their fortune in the manufacture of paper, and they owned a 194-acre estate, called “Endean,” in East Walpole, Massachusetts, overlooking the Neponset River.

For Leilie, Catherine was not just an art teacher, she was a friend despite their fourteen-year age difference, a friendship which would last over fifty years. Leilie spent a year learning about art under the watchful eye of Catherine until Catherine decided that Leilie should move to a formal art school. She spoke to William Biddle, who, as the husband of Leilie’s aunt Emily, had been acting as Leilie’s unofficial guardian. Catherine suggested that the finest art school for his charge was the Van der Wielen School. It was run by a young Dutch-Flemish artist, Francis Adolf Van der Wielen, who had immigrated to Philadelphia in 1868 after he had trained at the Antwerp Academy of Fine Art. He opened his art school as a way of countering the fact that he had begun to find it difficult to paint due to his failing eyesight. In 1872, seventeen-year-old Leilie Beaux enrolled at the school.

Most of Van der Wielen’s female students had come to him to learn about art and looked upon it as a delightful hobby but some of his students, like Leilie, looked upon art as a skill that would eventually earn them money. Although Leilie had doubts about her tutor, due to his poor grasp of the English language and the fact that his eyesight was starting to fail him, thus making his visual criticism of his students’ work questionable. However, she remained at his school for almost two years gaining knowledge of linear and aerial perspective and the principles of light and shade. In 1873, Van der Wielen married one of his more mature students and the couple left America for a new life in Europe. His art school would have closed but for Catherine Drinker stepping in and taking over the teaching.

In 1873 Cecilia(Leilie) Beaux reached the age of eighteen and decided that it was time to put her artistic skills to work to earn money for herself and thus gain a modicum of independence and also to bolster the family’s finances. In her autobiography she wrote:

“…My grandmother’s house was my home, and in it I was the youngest born, but I wished to earn my living and to be perhaps some day a contributor to the family expenses…”

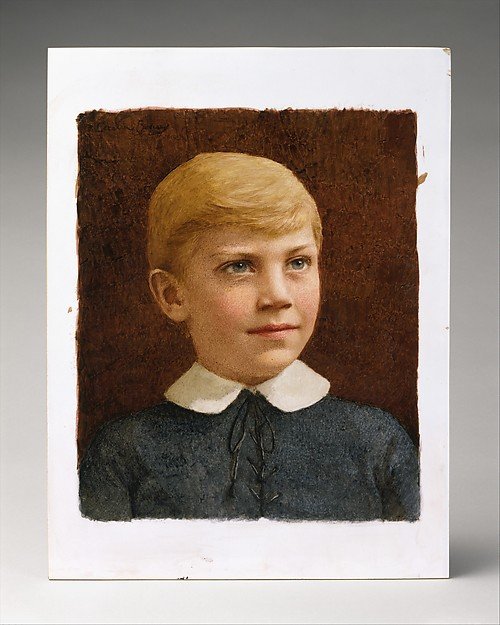

For a month she took lessons in china painting and found that in a short time she had mastered the delicate technique. She would produce portraits on large china plates. One of her early successes was a china plaque featuring a young gold-haired girl, the parents of the child were delighted.

From this came many commissions featuring paintings of young children. However, she never really took to this type of work saying:

“…Without knowing why, I am glad to say that I greatly despised these productions, and would have been glad to hear that, though they would never ‘wash off,’ some of them had worn out their suspending wires and been dashed to pieces. This was the lowest depth I ever reached in commercial art, and, although it was a period when youth and romance were in their first attendance on me, I remember it with gloom and record it with shame…”

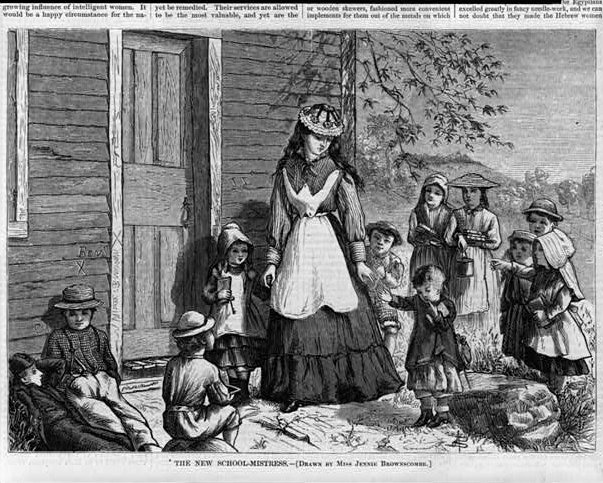

Catherine Drinker had taught art at Miss Sanford’s School for young ladies for many years but now, with taking over at Van der Wielen’s school she had to give up her post at the Sanford School and she recommended her protégé, Leilie to take her place. Leilie was taken on as a part-time drawing instructor at the school, teaching two classes, one morning a week. She would teach her young pupils how to draw, how to enlarge and how to shade. She taught there for three years and this led to her also giving private art lessons which earned her more money. In 1874, William Biddle introduced Leilie to a printer, Thomas Sinclair, of Thomas Sinclair and Sons. He and the Leavitts knew each other as they were fellow members of the Woodland Presbyterian Church and she was offered her first professional illustration job. Leilie had now finally launched herself into the art world and she decided that she needed to have a definite artistic identity and chose to revert to using her mother’s name. From thenceforth she was to be known as Cecilia Beaux.

As an aspiring artists Cecilia wanted the best artistic tuition that she could receive, given by the most talented tutors, and for her, this meant attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (P.A.F.A.) which was a museum and art school in Philadelphia, and was founded in 1805. In 1871 it had been closed for major reconstruction and was not re-opened until 1876. Another reason for Cecilia wanting to attend classes at this prestigious art academy was that in 1878 Catherine Drinker became the first woman to teach there. However, Cecilia’s uncle William was dead set against the idea of his “charge” attending the academy. Cecilia remembered her uncle’s argument for his decision:

“…I was a seemly girl and would probably marry. Why should I be thrown into a rabble of untidy and indiscriminate art students and no one knew what influence? So reasoned his chivalrous and also Quaker soul, which revolted against the life-class and everything pertaining to it. He put a strong and quiet arm between me and what he judged to be a more than doubtful adventure…”

Cecilia’s next step on the artistic ladder came by way of a former school friend from Miss Lyman’s School. Her friend, who had come from a wealthy background had spent her years after finishing her schooling “immersed in social gaiety” as a debutante but had now decided to take painting more seriously and had taken a studio and organised a class to be held three times a week to sketch and paint using a model. She invited Cecilia to join the class and her uncle, William Biddle thought this was a good idea and funded his wife’s niece participation. The work of all at the class was overseen on a fortnightly basis by the New York-based American painter William Sartain. Cecilia remembered the time well writing:

“…There were a few, only, in the class, all young, but all respectful toward what we were undertaking. It was my first conscious contact with the high and ancient demands of Art…”

…………………………to be continued

A lot of the information for the blogs featuring Cecilia Beaux came from two books:

Backgorund with Figures, the autobiography of Cecilia Beaux

Family Portrait by Catherine Drinker Bowen

and the e-book:

Out of the Background: Cecilia Beaux and the Art of Portraiture by Tara Leigh Tappert