Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

Observing things of beauty is one of the pleasures of life and in my blog today I am looking at the life of an artist who constantly depicted feminine beauty in his paintings. My featured artist is the Victorian Neo-classicism painter John William Godward. Victorian Neoclassicism was a British style of historical painting inspired by the art and architecture of Classical Greece and Rome. During the 19th century, ever more Europeans made the “Grand Tour” to the Mediterranean lands. For them, the highlight of the journey was visiting the ancient ruins of Italy and Greece and learning about the exotic cultures of the past, and it was this fascination which led to the rise of Classicism in Britain. Godward’s portrayals of female beauty was not merely “things of beauty” but of classical beauty which during his early days was very popular with the public.

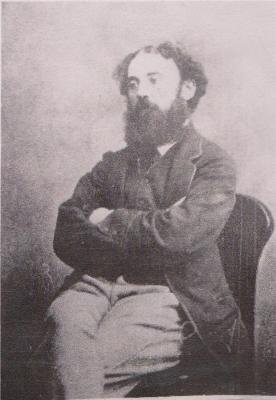

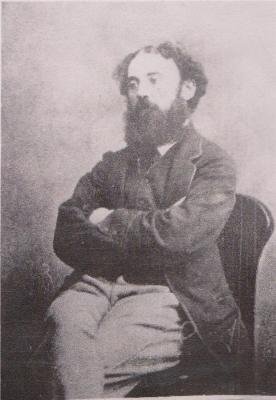

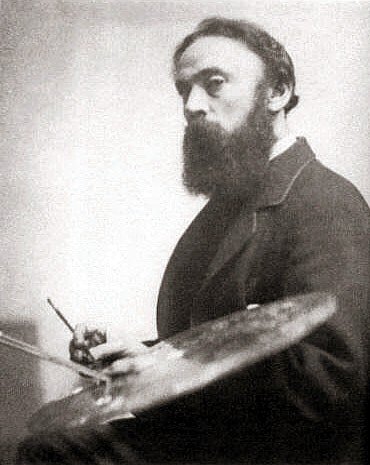

John William Godward’s paternal grandfather

John William Godward was born on August 9th, 1861. He was the eldest of five children of John Godward and Sarah Eborall. John’s father and the artist’s grandfather, William Godward, had been involved in the life assurance business and his grandfather had become quite wealthy through some wise investments in the Great Northern Railways which had been formed in 1846. John Godward Snr., the artist’s father, followed in his father’s footsteps and worked as an investment clerk for The Law Life Assurance Society at Fleet Street in London’s financial district. On the death of his father, John Godward Snr. inherited a sizeable amount of money and he and his wife Sarah, whom he married in June 1859, lived a comfortable life in their home in Bridge Road West which was then in the ashionable London district of Battersea. They lived an “upright” and were devout followers of the High Church of England.

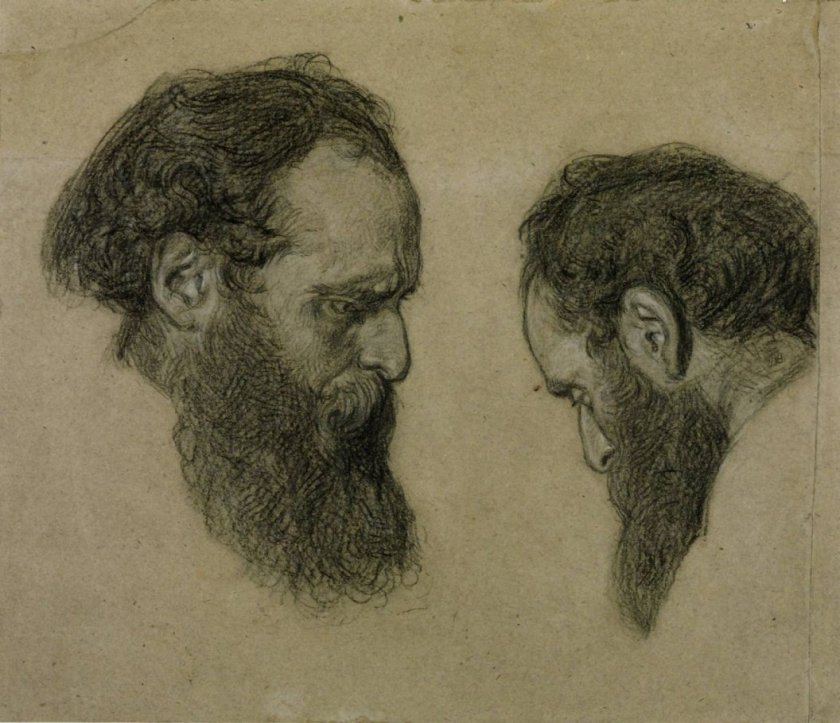

John William Godward’s father

Sarah Eborall, John Godward Snr’s twenty-six-year-old wife, gave birth to their first child on August 9th 1861 at their Battersea home. The baby was christened that October and given the names John and William after his father and paternal grandfather. Two years later in December 1863 their second child, Alfred was born. In 1864 the family moved from Battersea to Peterborough Terrace, Fulham, later renamed Harwood Terrace. Fulham at the time, and unlike today, was a rural area with its farms and market gardens. In February 1866 Sarah gave birth to her third child, a daughter, Mary Frederica, who was known affectionately as “Nin”. With a growing family John Snr, Sarah and their three children moved to larger rented premises in Peterborough Villas, close to their previous home.

Two further children were born, Edmund Theodore, known as Ted, in November 1869 and their youngest, Charles Arthur, in June 1872. The Godward family was now complete with five children and the size of the family probably dictated that they needed larger accommodation and somewhere around 1872 they all moved to Dorset Road Wimbledon

Little is known about John William Godward’s schooling but as his family were well-off middle-class parents he may have been enrolled at one of the many private schools in the Wimbledon area. It is thought that he developed a love of drawing during his schooldays. He was brought up in a very strict household in which maternal and paternal love was in short supply. Both his parents were very controlling and John William had few friends. His father, a devout Christian and church-goer, was both strict and puritanical and expected his word to be law and as far as he was concerned all his sons would, on leaving school, follow in his footsteps into the business world and, in particular, into the world of insurance and banking. Whereas John William’s three brothers, Alfred, Edmund, and Charles happily entered the world of insurance much to their father’s delight, John William Godward, his eldest son proved, in his mother and father’s eyes, to be a disappointing failure who although forced, at the age of eighteen, into working as an insurance clerk with his father, hated every minute of this alien world of finance.

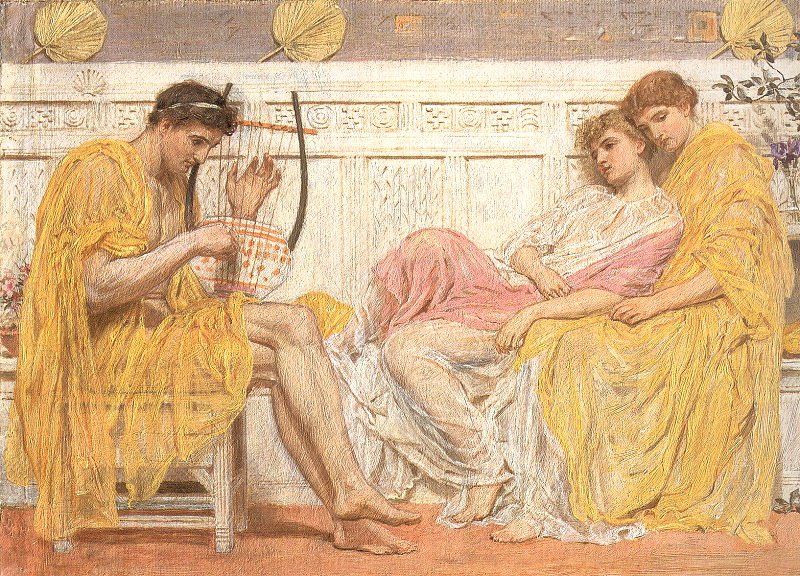

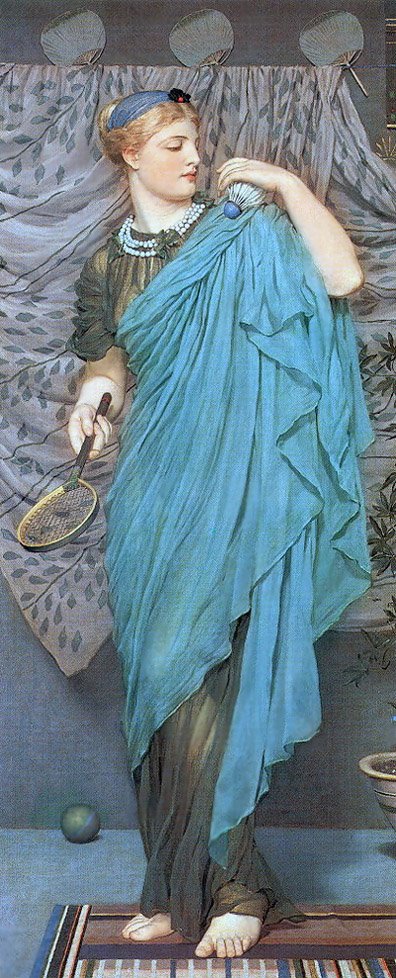

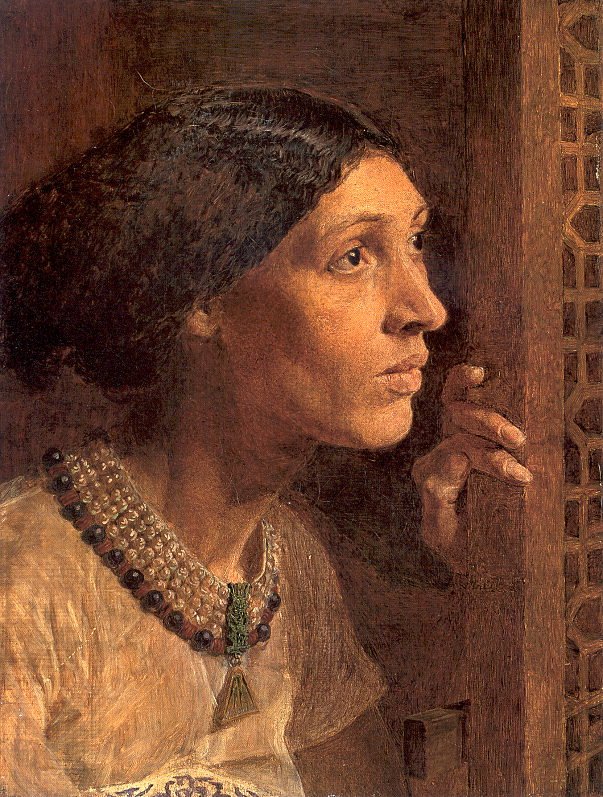

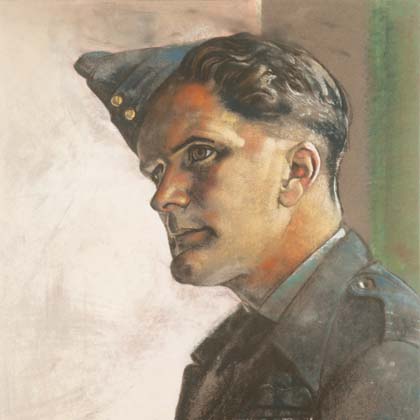

Study of a model, possibly Hetty Pettigrew

John Godward probably realised that his son was not going to remain in the insurance profession and because of his son’s propensity for art, decided that rather than let him idle his time as a fine artist he would arrange for him to study architecture and design. In the eyes of his parents, an architect had a more acceptable and honourable ring to it than that of an artist. Between 1879 and 1881, his father arranged for his son to study under William Hoff Wontner, a distinguished architect and designer and friend of the family, in the evenings whilst retaining his day job as an insurance clerk. John William Godward worked alongside Wontner’s son William Clarke Wontner, who was also interested in fine art and exhibited some of his portraiture at the Royal Academy exhibitions. William Clarke Wontner soon became a popular portrait painter who received many commissions from patrons for landscapes and murals to decorate interiors of their homes. One can imagine that the youthful John William Godward was inspired by his friend’s blossoming career in fine art and was more than ever determined to follow a similar path. The two men would remain good friends for the years that followed. The other bonus in working in Wontner’s architecture office was that Godward was able to develop his skills in prospective and drawing of architectural marble elements which would feature in his later paintings. In 1881 William Hoff Wontner died but his son carried on training the twenty-year-old, Godward and it is almost certain that Wontner’s success as an artist further intensified Godward’s desire to paint for a living, a decision which would cause havoc with his relationship with his mother and father.

One of the earliest works completed by John William Godward was a small watercolour portrait (4.5 x 3.25 inches) of his paternal grandmother, Mary Perkinton Godward. She had died in 1866 when the artist was just five years old and so it is thought that he used a family photograph to complete the work.

There is some doubt as to if, when and where John William Godward received formal artistic training. Knowing his family’s vehement opposition to their son becoming a professional fine artist he is unlikely to have had his family’s backing to enrol at the likes of the Royal Academy of Art School and in fact there is no record of him attending any of their full-time courses. However, we do know that in 1885, his friend and erstwhile mentor William Clarke Wontner taught at the prestigious St John’s Wood Art School, a feeder school to the RA School, and it may be that Godward also attended this establishment. We also know that some of the visiting artists to this art school were Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Frederick Leighton, and Sir Edward John Poynter whose art certainly influenced Godward.

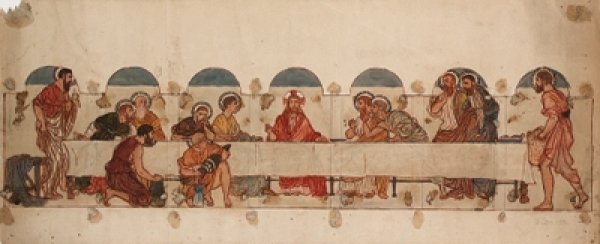

Another reason to believe that Godward was receiving some formal training was a painting he completed around this time entitled Giotto Drawing on a Tablet which depicts the Italian artist, Giotto di Bondone, as a young shepherd drawing sheep. The depiction is based on a passage from Giorgo Vasari’s1550 book, Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori (Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), which recounts that Giotto was a shepherd boy, a merry and intelligent child who was loved by all who knew him. The great Florentine painter Cimabue, one of the two most highly renowned painters of Tuscany, discovered Giotto drawing pictures of his sheep on a rock. The depiction was so lifelike that Cimabue approached Giotto and asked if he could take him on as an apprentice.

Godward’s painting bore all the hallmarks of a “diploma piece” – a work of art which had to be submitted for critical assessment by tutors and it had to have the major genre elements taught in the art schools of the day. It had a figure, a group of animals and a landscape, all of which were mandatory elements in order to demonstrate an artist’s technical expertise. Having said all that, there are no definitive records of John William Godward attending any local art colleges.

Another early work by Godward was an 1883 portrait of his sister, entitled, Portrait of Mary Frederica “Nin” Godward. The artist has depicted his sister shoulder-length in profile to the left. This was Godward’s first known oil painting.

Godward’s 1883 painting Country House in the 18th Century shows his early style, so dissimilar to the Neo-classical paintings we now associate with him. It is so different in style that it may just have been a copy Godward made of another artist’s work

What every artist needs at one time or another is a good model. Artists’ models often worked for more than one artist and the best were in high demand. Enter the Sisters Pettigrew. On the death of her husband William Pettigrew, a cork cutter, and because of the dire need to feed her thirteen children, his widow Harriet Davies took the advice of her artist son that three of his sisters, Lilly, Harriet and Rose, all with their masses of hair and exotic looks would make ideal Pre-Raphaelite artist’s models, and so in 1884, she took them to London where they became an instant hit with many artists such as John Everett Millais, Fredrick Lord Leighton, William Holman Hunt, Edward Burne-Jones, James McNeill Whistler and John William Godward. Rose Pettigrew wrote about the experience six decades later:

“…every great artist of the land” was clamouring for one of the “Beautiful Miss Pettigrew’s” to pose…”

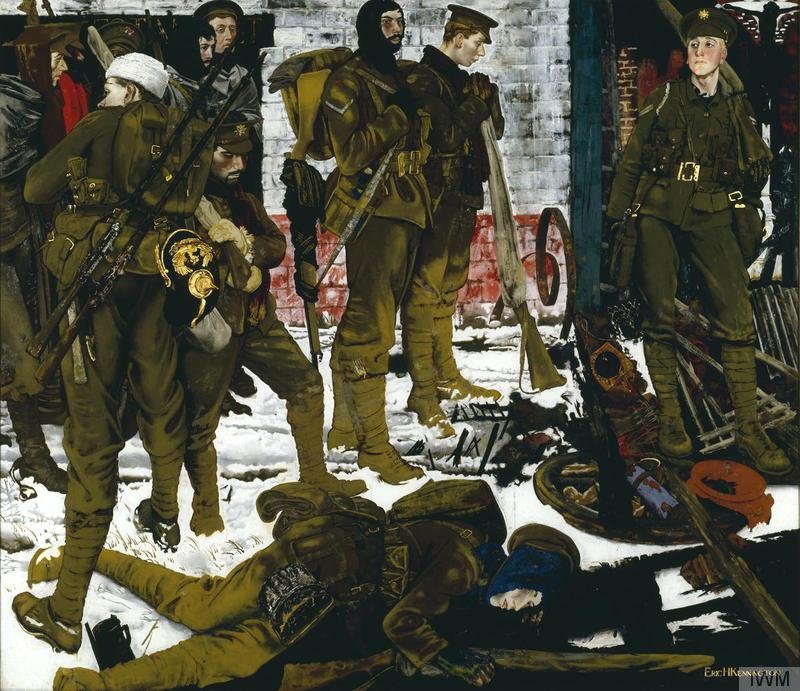

Their first time the girls appeared as artist’s models was when John Everett Millais used all three sisters in his 1884 painting, An Idyll of 1745, which depicts three young girls listening to the music played by a young British fifer. Behind the fifer is a Loyal volunteer, seemingly enjoying the moment. In the background is a British Army camp, likely where the fifer and volunteer came from. From what the artist’s son said the three young girls were almost more trouble than they were worth, saying:

“…more trouble than any [models] he ever had to deal with. They were three little gypsies … and with the characteristic carelessness of their race, they just came when they liked, and only smiled benignly when lectured on their lack of punctuality…”

John William Godward completed a portrait of the beautiful seventeen-year old Lily Pettigrew in 1887. She was the most beautiful of the three as her sister later wrote:

“…My sister Lily was lovely. She had [the] most beautiful curly red gold hair, violet eyes, a beautiful mouth, classic nose and beautifully shaped face, long neck, well set, and a most exquisite figure; in fact, she was perfection…”

Nineteen year old Harriet (Hetty) Pettigrew featured in Théodore Roussel’s famous 1887 painting The Reading Girl. Look what a fine model she is in the natural way she relaxes and seems so comfortable, naked in front of the artist. Hetty had met Roussel in 1884 and from becoming his model, then, despite Roussel being married, became his mistress and gave birth to their daughter, Iris around 1900. When Roussel’s wife died, instead of legalising his relationship with Hetty and their child, he married Ethel Melville, the widow of the Scottish watercolour painter, Arthur Melville. Once Roussel re-married in 1914, Hetty never sat for him again. Their close bond was over.

The Pettigrew sisters are also thought to have introduced Godward to other artists who were members of the Royal Society of British Artists. The Society had been founded in 1823 but had grown very little in its first fifty years of existence due to financial problems but then it came into its own around 1886 when its president was James McNeil Whistler. Whistler wanted to inject some life into the Society by encouraging it to accept new young artists such as Godward, who for the next three years showed works at their exhibition. Whistler’s tenure at the Royal Society of British Artists lasted only two years when he was asked to stand down. Godward, however, was eventually elected as a member of the Society in 1890.

In 1887 Godward had his painting entitled The Yellow Turban accepted at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. This of course was a great moment for the twenty-six-year-old artist and it was probably, begrudgingly, the first thing about their son’s desire to be a painter that pleased his parents’ middle-class values. Whether their son was happy, mattered little to them. His achievement or lack of it was everything in their eyes. Initially they hoped he would follow the family tradition and work in the insurance business. They even “allowed” him to study art with Wontner in the evenings providing he stayed with the insurance company and there was even a hope he would, through his association with Wontner, enter the prestigious world of architecture. Their dreams for their son were later lowered to believe he may become, as a last resort, a teacher of art – anything than have to suffer the ignominy of having their son become a penniless artist.

For Godward he was reaching a crossroad in his life. He was twenty six years of age, still living at home with his parents who could not and would not share and support his ambition to become an artist. He must have felt the overpowering parental pressure and for this reason suffered mentally. He needed to break free but what price would he have to pay for this freedom?

……………..to be continued

Most of the information for this and my next blog about John William Godward came from a 1998 book by Vern Grosvenor Swanson entitled J.W.Godward: the Eclipse of Classicism.