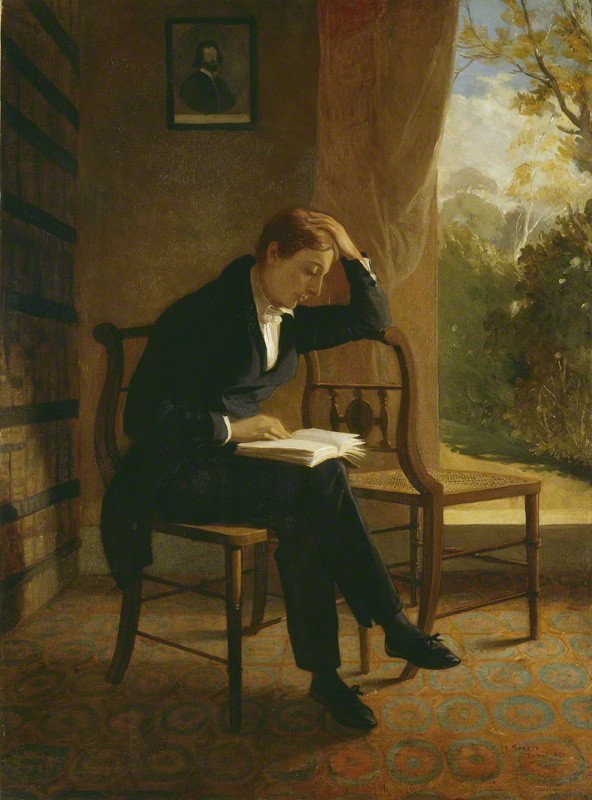

by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale (1898)

Today I want to look at the life of Pre-Raphaelite painter, Mary Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, who was born thirty-four years after the original seven English Pre-Raphaelites painters formed an artistic group, known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, whose aim it was to reject classicism and return to the vibrant colours and complex details of earlier Italian and Flemish art. But while the Brothers were starting to go their own way artistically and the Brotherhood was heading for extinction, their ideas were not.

When I visited the Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde at the Tate Britain a week ago I was struck by just the few paintings on display which had been painted by women. There were a couple of watercolours by Dante Rossetti’s model and mistress, Elizabeth Siddall. There were some early photographs taken by Julia Margaret Cameron and some embroidery by Jane Burden who later became Mrs Jane Morris, but little else from any other female Pre-Raphaelite painters. So it was very pleasing to find that a local art gallery, not too far from me, The Lady Lever Gallery in Port Sunlight, Wirral had just put on a small exhibition of work by a feminine Pre-Raphaelite painter entitled A Pre- Raphaelite Journey which showcased the art of Mary Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale. In my next couple of blogs I want to look at the life of this gifted female artist and feature some of her paintings.

Mary Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale was born in the prosperous London suburb of Upper Norwood, Surrey in 1872. She was brought up in an affluent household which, besides the family, also housed four live-in servants and a governess. Eleanor was the youngest of five children. Her father Matthew was a Lincoln Inn’s barrister who had married Sarah Anna Lloyd, the daughter of a judge from Bristol. At this juncture in Victorian England, parents expected their sons to prosper at school and go onto university, after which they would secure well paid, high status professions. Daughters were not expected to achieve any great academic status but would harness all their efforts into securing a “good” marriage. Mary Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale’s two brothers achieved all that was expected of them. Both Charles and John Fortescue-Brickdale graduated from Oxford University, following which Charles, like his father became a lawyer and John followed a career in medicine. Of the three daughters, Anne had died at the age of six leaving Eleanor and Kate to fulfill their parents’ plans of finding themselves “good” husbands. However, unlike their brothers, they were not to realize their parent’s wishes as neither married.

The Fortescue-Brickdale family had tentative ties to the world of art with Eleanor’s father being a fellow Oxford university student of John Ruskin and later Eleanor’s brother Charles, who was an amateur artist, would attend Ruskin’s lectures at Oxford. Eleanor had originally shown an interest in painting and drawing but merely as a pastime. As she grew older, she began to take art more seriously and consider it as a possible future profession. In 1889, aged seventeen, Eleanor enrolled at the Crystal Palace School of Art, Science and Literature. It was not considered a prestigious art school and did not have any famous painters on the staff but it was close to where Eleanor lived and so was deemed fit for purpose. The school was open to both boys and girls but the science classes were only for young men whilst the art classes were solely for young women. The only mingling of the sexes occurred in the music classes.

In 1894, tragedy was to strike the Fortescue-Brickdale family with Eleanor’s father being killed whilst climbing in the Swiss Alps. Eleanor having gained a basic knowledge of art and artistic techniques whilst at the Crystal Palace School of Art, realised that to become a professional artist she needed to attend a much more professionally run art establishment and in the mid 1890’s she enrolled at the St John’s Wood Art School. The aim of this school was to train students for the Royal Academy Schools and it was very successful at this, as between 1880 and 1895, 250 out of 394 students admitted to the Royal Academy had come from St John’s Wood Art School and furthermore, of the 86 prizes awarded to students by the Royal Academy, 62 had been ex-pupils of St John’s Wood Art School. To achieve entry to the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer one had to submit certain prescribed pieces of work. If the submitted works were considered acceptable, the candidate then had to endure a three month probationary period before being allowed on to a full-time course. In January 1895, on her third attempt to become a probationer, Eleanor was admitted. Despite the initial problems of being accepted as a probationer, her work during her probationary period was looked upon as being so good that she was allowed to embark on a full-time course after just three weeks.

Eleanor managed to cover the costs of her first year at the Academy by selling some of her work which she used to work on before and after attending the Academy School. Although this was a financially good option for her, it made her days very long. Two years later in 1897 she was awarded a prize for her design work and the recognition she received for this led to a number of commissions, including one from her brother Charles’ legal practice, and one for illustrating a book entitled A Cotswold Village, which was written by her brother-in-law, J Arthur Gibbs. Soon she became one of the most visible female artists of her time. One must remember that Eleanor was a single woman, had not gone to a public school instead had been home educated, did not go to university and so lacked the opportunity in later life to cultivate connections with ex students. The one thing that was going for her was the sector of society in which she grew up. Their neighbourhood family friends included well-to-do bankers and lawyers, landed families who had houses in town, all of which needed decorating and acquiring paintings to hang on their walls. These were people with disposal incomes. They were also readers of upper-class publications such as Country Life and The Ladies Field and Eleanor managed to find work at these magazines using her well-loved artistic design skills. She contributed illustrations to these magazines for over ten years and from people seeing and admiring her work she began to build up a sizeable patronage

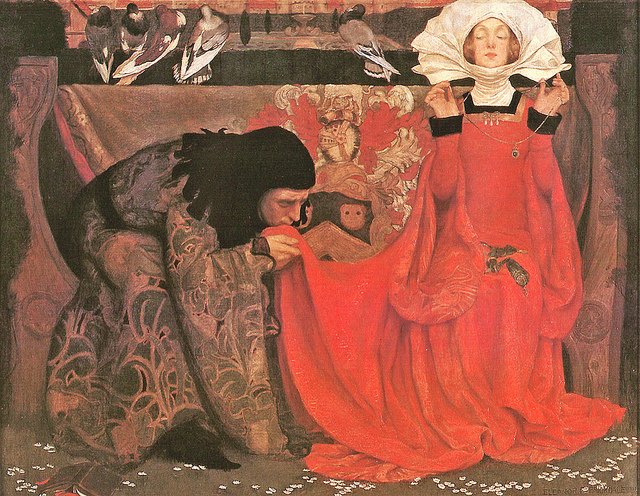

In 1898 she had her first major work of art entitled The Pale Complexion of True Love accepted for the Royal Academy Exhibition of that year. This is my featured painting of the day. The title of the work is taken from Act 3 Scene IV of Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy, As You Like It, when the elderly shepherd, Corin speaks of the shepherd, Silvius’ unrequited love for the shepherdess, Phebe:

“…If you will see a pageant truly play’d,

Between the pale complexion of true love

And the red glow of scorn and proud disdain,

Go hence a little and I shall conduct you,

If you will mark it…”

The first thing that strikes you with this painting is the sumptuous red of the lady’s gown. It is interesting how the artist has used such a bright spectrum of colours. To many people, the Pre-Raphaelite painters use of bright colours is too garish and lacks subtlety. To others it is this vibrancy of colour which enhances the work. I will let you decide which camp you find yourself in.

In my next blog I will continue the life story of Eleanor Fotrtescue-Brickdale and look at another of her paintings.