Part 2. Isabel Bishop

“…I hope my work is recognizable as being by a woman, though I certainly would never deliberately make it feminine in any way, in subject or treatment. But if I speak in a voice which is my own, it’s bound to be the voice of a woman…”

-Isabel Bishop

Isabel Bishop, 1959. Photo by Budd ( New York N.Y.). Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

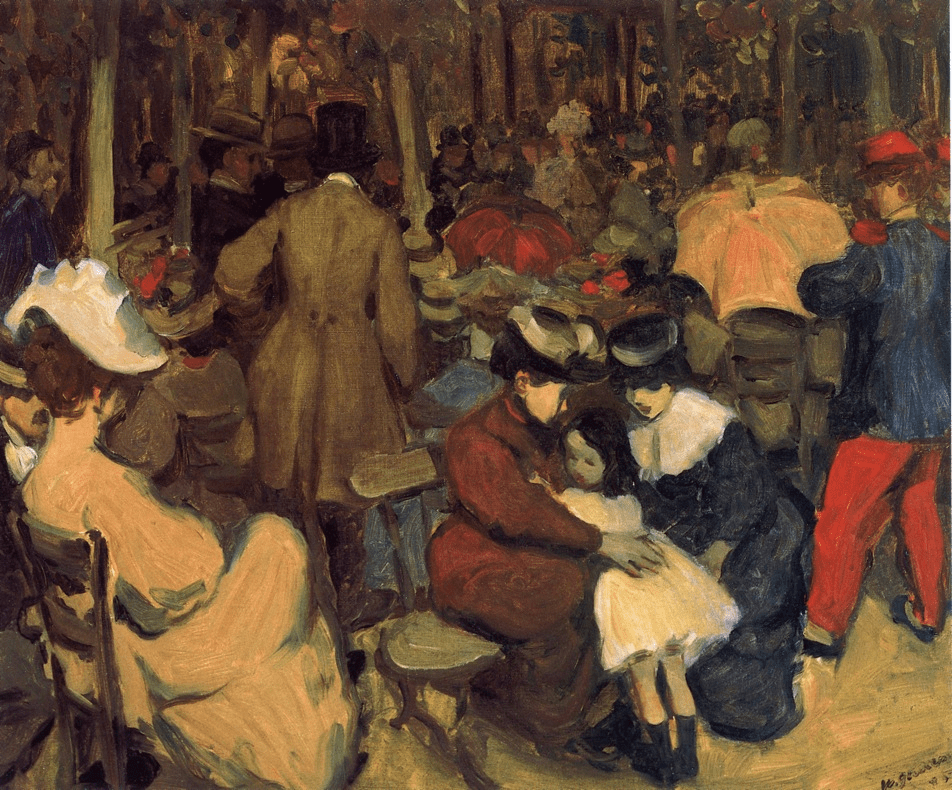

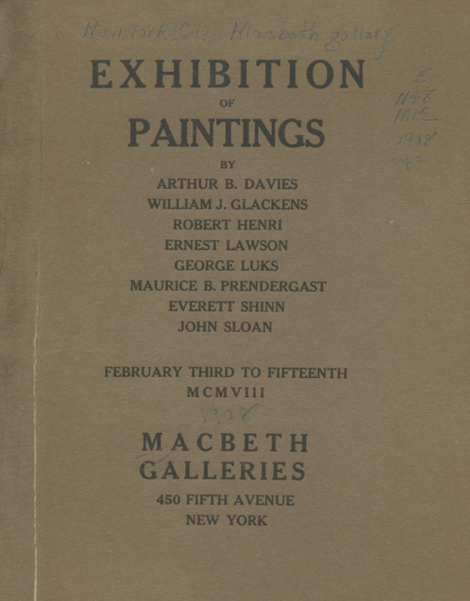

The Ashcan School of painters was the artistic movement that depicted Urban Realism in America during the late 19th and early 20th century. A few decades later another group of American realist painters, who were also based in New York city, began to focus on everyday life in the city. For these artists, it was all about the bustling area which centred around 14th Street and Union Square in Lower Manhattan during the Depression era. They became known as the Fourteenth Street School of Artists. One of these artists was Isabel Bishop.

Female Head by Isabel Bishop

Isabel Bishop was the youngest of five children born on March 3rd 1902 in Cincinnati, Ohio, to John Renson Bishop and Anna Newbold Bishop. Her parents were descendants from East coast mercantile families but although they came from “old money” they were considered middle-class and often struggled financially. Isabel’s parents were both highly educated individuals. Her father was a Greek and Latin scholar and had a Ph.D in history. Her mother was a writer and an activist for women’s suffrage. The family frequently moved from town to town for financial reasons and to gain employment. Wherever they set up home, Isabel’s father, John, would find work at the local school where he often rose to become its principal and in some cases took ownership of the school.

Ice Cream Cones by Isabel Bishop

In 1887 the couple had their first children, twins, a boy and a girl, Mildred and Newbold and in 1890 another set of twins, once again a boy and a girl, was born, Remson and Anstice. This enlargement of the family caused financial hardship and her father had to continually look for better paying jobs. Isobel did not remember much about the two sets of twins as by the time she was born they were away at boarding school or college. According to Isabel her parents were very different in temperament. Her mother was a free spirit but very strong-willed and in her 1987 interview she recalls an incident that had repercussions on her father’s life:

“…It was hard on my father that she was strong. For one thing, in Detroit, Michigan, women were not supposed to be strong. She simply liked what she liked and that was it. One time she was asked to go down to the court and testify in some case. She went down, but she wouldn’t swear to be telling the truth. She was asked by the court why she wouldn’t and she said, “I don’t believe in God.” It was in the Detroit papers with the headline:

“SCHOOL PRINCIPAL’S WIFE DOESN’T BELIEVE IN GOD”

I really felt for my father. I mean, a school principal! His life was pretty impossible after that…”

Two Girls with a Book by Isabel Bishop

Although born in Cincinatti Isobel and her parents moved to Detroit a year after she was born. In 1914, when she was twelve years of age, Isabel was enrolled in Saturday morning life drawing classes at the John Wicker Art School in Detroit. From there, at the age of sixteen, and once she had graduated from High School, she left Detroit and went to New York. It was here that she enrolled at the School of Applied Design for Women, where she studied illustration. In 1920, aged eighteen, Isabel, wanting to enhance her artistic knowledge and skills, attended the Art Students League where her first tutor was Max Weber, whom she disliked and who gave her a hard time. Later she was tutored by Kenneth Hayes Miller, another artist associated with the Fourteenth Street School who couldn’t be more different than Weber. Other tutors were Guy Pène du Bois, Robert Henri and Frank Vincent DuMond.

Portrait of Isabel Bishop by Guy Pene du Bois (1924)

According to Helen Yglesias’ 1989 biography Isabel Bishop, although Weber treated Isabel harshly and she felt intimidated by Robert Henri, in Kenneth Hayes Miller she found a mentor who, in her words, was “intellectually stimulating, not stultifying, a fascinating person who presented all sorts of new possibilities, new points of view.”

Isabel Bishop’s 9 West 14th Street Studio (no longer extant) highlighted in red, 14th Street, north side, west from Fifth Avenue. June 11, 1933.

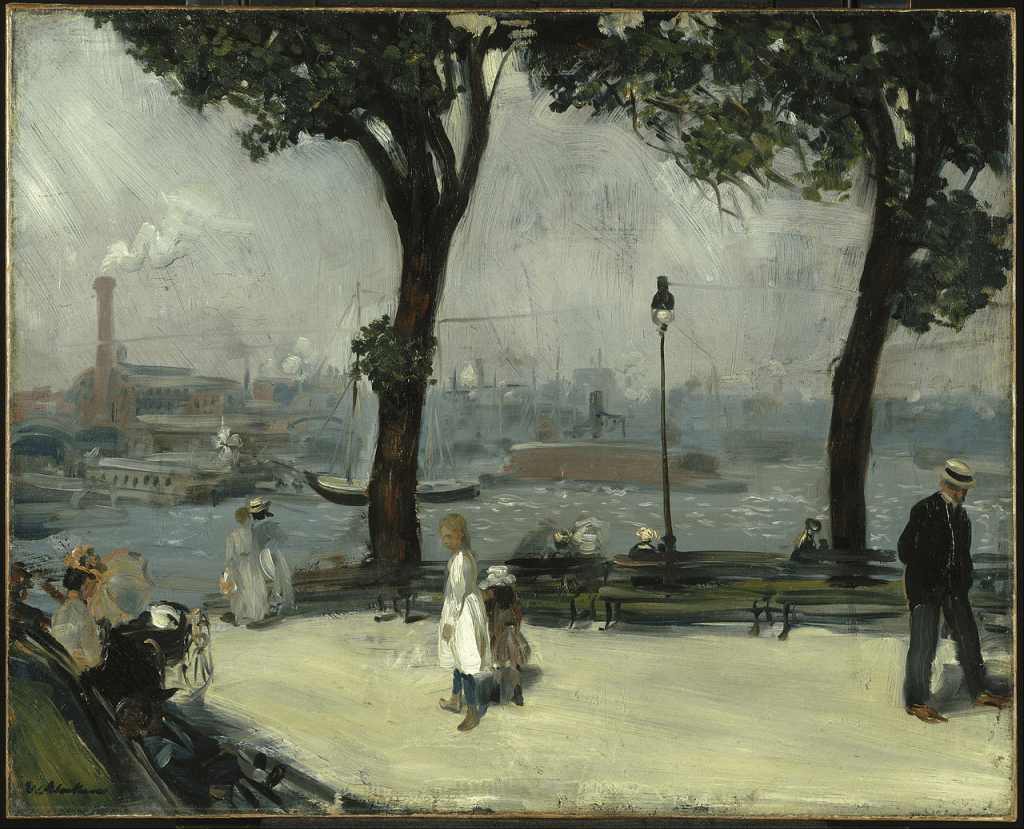

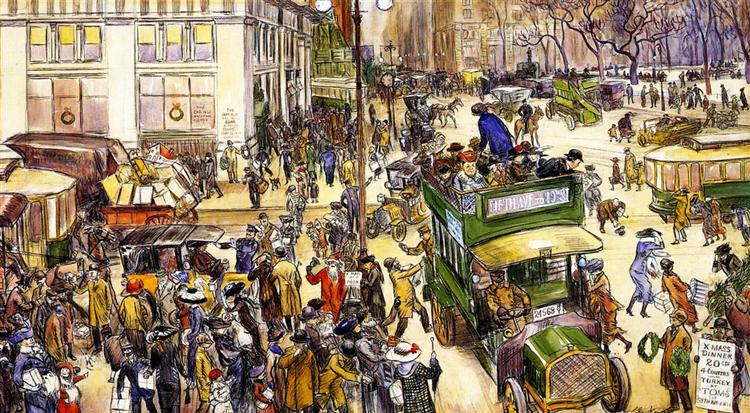

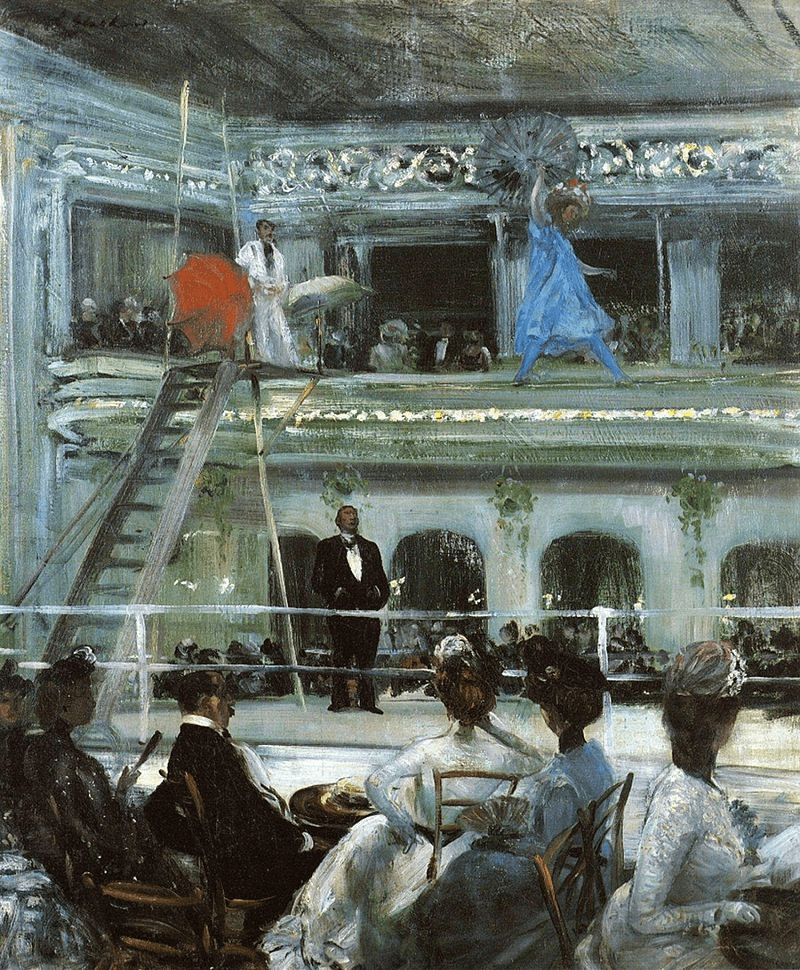

Another friend she made at the Art Students League was Reginald Marsh, who made fleeting visits to the classes at the Art Students League whilst she was student there and this friendship led to her being witness to the working-class life of the city. In 1926, she went to live at 9 West Fourteenth Street, which was a short distance from where Marsh lived and it was in this vicinity that she kept her studio that overlooked Union Square at Broadway and East Fourteenth Street and remained there until 1982. From the windows of her studio she was able to witness the daily activities in Union Square. Fourteenth Street in the 20s and 30s was referred to as “The Poor Man’s Fifth Avenue.” It was a bustling center for bargain shopping and bawdy entertainment in the form of burlesque shows and movie theatres for everyday working-class New Yorkers.

Still Life with Orange #1 by Isabel Bishop

Her friendship with fellow student, Reginald Marsh, encompassed many lunch or dinner dates when they discussed their day’s work. She affectionately recalled that they each paid for their own fifty cent meal and occasionally Marsh would take her to a Coney Island dance marathon or backstage at Minsky’s Burlesque. She recalled that it was great going with Reggie, and whilst there he would sketch the goings-on at the Burlesque show. She said that there were a number of occasions, the owner, Minsky bought Reggie’s work.

The Artist’s Table by Isabel Bishop

Isabel loved the area around Union Square and would regularly visit the Square itself, sketching for hours on end. She remembered those days saying:

“…I adored it. Drawing nourished my spirit; it was like eating. I got ideas there, for drawing is a way of finding out something, even though it might only be the discovery of a simple gesture…”

If she liked one of her sketches, she would turn it into an etching or make a painting from it. She soon became known for depicting urban life and was a leading member of the Fourteenth Street School of artists.

14th Street by Isabel Bishop

The Great Depression began in 1929 and nobody seemed to want to spend money buying the work of an unknown female artist, especially one who had not even had a solo show. Money was tight, people were losing their jobs and America had fallen into the grip of the worst depression in history and most Americans were worried about how they could survive the disaster that had befallen the nation. Isabel went from art gallery to art gallery hoping that they would accept her paintings but with little luck. It was a very depressing and frustrating time in Isabel’s life. A turning point came when Isabel met Alan Gruskin. Gruskin had hoped to become an artist, but while still a student realized that his talents were better suited to art administration than painting. On graduating from Harvard he worked at a New York gallery that specialized in the works of the Old Masters. He left there and returned home hoping to start a career as an author but that never came to fruition so he returned to Manhattan and, in 1932, opened the Midtown Galleries at 559 Fifth Avenue. He specialised in artwork by living American artists and in that year he staged a solo exhibition of Isabel’s paintings.

Dante and Virgil in Union Square by Isabel Bishop (1932)

Isabel Bishop’s paintings focused on the ordinary people of New York City, and in particular, those in her neighbourhood around Union Square and 14th Street. However, her 1932 painting entitled Dante and Virgil in Union Square was extraordinary with her inclusion of Dante, in the red cloak, and Virgil, with a laurel wreath on his head, which makes this work memorable. Isabel said she was motivated when she read the translation of Dante’s Inferno, the first part of Italian writer Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century narrative poem The Divine Comedy with its tales of life in the underworld. In her depiction, Isabel likened the hordes of poor souls that confronted Dante and Virgil in the various levels of hell with the hordes of human beings that daily passed through Union Square at rush hour. In the painting we see a crowd of people at Union Square, the equestrian statue of George Washington in the centre framed by the Union Square Savings Bank and other buildings in the background. It is a very busy scene a woman leading her child by the hand, pairs of women walking away from the crowd, and a number of working class men, portrayed in darker colours, facing into the Square seem completely unaware of the classical figures, who stand in the shadowed foreground of the sidewalk, as if embodying the evaluating gaze of another era.

At the Noon Hour by Isabel Bishop (1936)

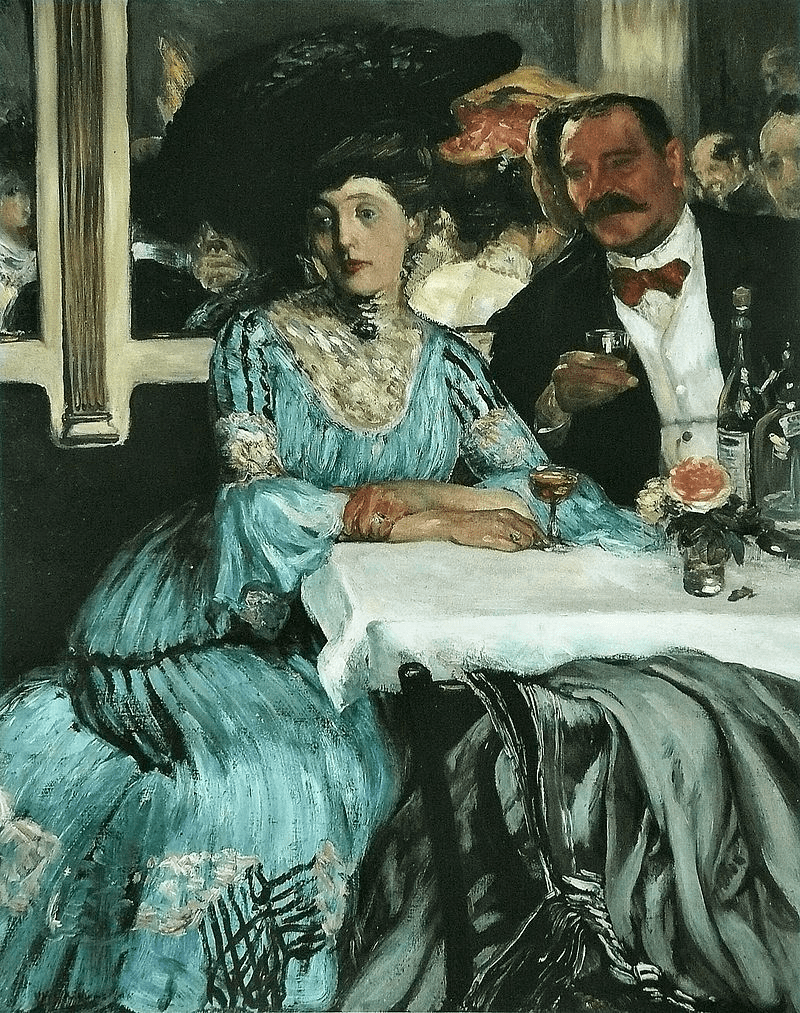

In Ellen Wiley Todd 1993 book, The “New Woman” Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street, she describes the New Woman of the 1920s and 1930s as:

“…being a moderate sort, who hoped to capitalize on new job possibilities and to make herself attractive with the mass-produced products of the clothing and cosmetics industry…”

Hearn’s Department Store-Fourteenth Street Shoppers by Isabel Bishop (1927)

The entrance to Hearn’s Department Store was right across the street from Isabel Bishop’s studio and she realised that it was the perfect place to find and observe this “New Woman.” Isabel Bishop’s Hearn’s Department Store—Fourteenth Street Shoppers was completed in 1927, the same year that she enrolled in Kenneth Hayes Miller’s mural painting class at the Art Students League. It depicts the city’s middle-class shoppers who are wearing the latest fashions and who visit the shops around Union Square in order to pick up the latest bargains.

Two Girls by Isabel Bishop (1935)

In 1935 Isabel completed her painting entitled Two Girls. It was yet another of her works which depicted young working women. In this painting we see a close-up of two smartly dressed figures seemingly engaged discussing the contents of a letter. Isabel used two models for this depiction and for this work she used Rose Riggens, a server at a restaurant where Isabel often had breakfast, and Riggens’ friend Anna Abbott. The work exudes both warmth and tranquillity which counters the dire economic circumstances of the Great Depression in the 1930s. This painting which took her twelve months to complete was one of Isobel Bishop’s most well-known works and was originally shown at the Midtown Galleries in New York. It is now part of the city’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Encounter by Isabel Bishop (1940)

In her 1940 painting entitled Encounter we witness an exchange occurring between a man and a woman though the circumstance of this meeting remains unclear. From many of her paintings we can deduce that Isabel was an insightful observer of everyday activities of young women who visited offices and stores in her neighbourhood. Her works present working women as vivacious subjects for the American Art Scene, which centred on the daily lives of the city’s population. At a time of great unemployment Isabel found it easy to employ young unemployed clerical workers to pose for her. In this work, she depicts a young woman and her boyfriend, with whom she is having a rather stormy romance. The painting can be seen in the St Louis Art Museum.

Tidying Up by Isabel Bishop (1941)

In her 1941 painting Tidying Up, we see a woman, perhaps a secretary or salesperson, using a pocket mirror to check her teeth for lipstick smudges. Isabel liked to depict working-class women during their idle moments away from their jobs. She spent more than a decade depicting secretaries, salesclerks, and blue-collar workers who lived and often worked in and around Union Square. She favoured subjects of women who were simply going about their everyday lives, eating, talking, putting on makeup, and taking off their coats. It was these mundane actions along with facial expressions that Isabel Bishop believed divulged the character and temperament of the people she portrayed. This painting is part of the Indianapolis Museum of Art collection.

Girl Reading by Isabel Bishop (1935)

Bishop remained on Union Square, where she kept a studio until the end of her life. The area around Fourteenth Street and Union Square remained foremost as the subject matter for her paintings. She received many awards during her life and she was elected an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1940 later in 1941 she was elevated to full Academician. She received a Benjamin Franklin Fellow at the Royal Society of Arts in London and was also elected a Member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1944 and was the first woman to hold an executive position in the National Institute of Arts and Letters as vice-president. In 1979, she was awarded the Outstanding Achievement in the Arts Award presented to her by President Jimmy Carter.

Self portrait by Isabel Bishop (1927)

Isabel Bishop died on February 19th 1988 two weeks before her eighty-sixth birthday.

Most of the information for this blog came from the following excellent websites:

Oral history interview with Isabel Bishop,

1987 November 12-December 11