As promised yesterday my blog today carries on looking at the life of Camille Pissarro and one of his later paintings.

In 1872 Pissarro returned to Pontoise, where he once again set up home. His friendship with Cézanne was re-established and Pissarro mentored his friend in the technique of painting “patiently from nature”. Cézanne was to later to comment about his relationship with Pissarro and how his mentoring made him change his artistic style saying:

“…As for old Pissarro, he was a father to me, a man to consult and something like the good Lord…”

Pissarro was determined to create an alternative to the Salon. He wanted a society of artists who would work together and become a type of cooperative. It took almost four years to achieve his aim . Artists petitioned for a new Salon des Refusés in 1867, and again in 1872. Both requests were denied and so during the latter part of 1873, Pissarro along with Monet, Sisley and Renoir organized the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”). Its purpose was to exhibit their works of art independently. They soon had fellow artists like Cezanne, Berthe Morisot and Degas interested in the scheme and all agreed to boycott participation in the Salon in 1874 and exhibit only at their exhibition. The exhibition took place in January 1874 at the studio of Gaspard-Félix Tournachon , known as Nadar, in the Boulevard des Capucines and this exhibition of their work was later to become known as the First Impressionist Exhibition. Works in this exhibition included five paintings from Pissarro. The names of the other artists who exhibited works in this exhibition reads like a Who’s Who” of famous artists. Included in the exhibition were works by Monet, Renoir, Guillaumin, Béliard, Sisley, Cézanne, Degas and Morisot. This First Impressionist Exhibition was not received favourably by the critics and Pissarro was disheartened by their criticism. He wrote to the art critic Théodore Duret, who was sympathetic to the Impressionist cause, expressing his disappointment with the adverse criticism:

“…Our exhibition goes well. It is a success. The critics destroy us and accuse us of not having studied; I am returning to my work, it is better than reading the reviews…”

So why did the majority of art critics hate the works on show? One should remember that the critics were brought up on the art of the Salon with its accepted works portraying religious, historical any mythological settings and so the paintings put forward by the Impressionists, including Pissarro, depicted commonplace street life and people busying themselves in their daily routine and was considered by the critics as both facile and some even went further by declaring them vulgar. The critics considered a lot of the Impressionist works as being “unfinished” in comparison to the works seen at the Salon. They commented that the way the brushstrokes of the Impressionists works were visible which, to their mind, meant it had been done in haste and often completed in a solitary sitting. In comparison they praised the Salon painters who to them were the “real” artists and who spent hour after hour carefully perfecting each part of their works.

The year of this First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874 proved a bad year for Pissarro. His artworks were not selling and he had to endure a personal tragedy with his nine year old daughter Jeanne dying the week the exhibition opened. However, Pissarro stuck to his belief in the Impressionist movement and exhibited no fewer than twelve works in their second exhibition in 1876. Three years on the Impressionist grouping was starting to fall apart with Renoir, Sisley and Cézanne having left. There was also now a split amongst the remainder of the group with Degas on one side who wanted to bring in new artists and Caillebotte and Pissarro on the other who wanted to maintain the status quo. Degas also laid down the rule for the Impressionist group that any artist putting forward work to the Salon could not enter work in that year’s Impressionist exhibition. This was a major dilemma for some of the group who believed that to become a respected artist and command a good price for their works they had to exhibit at the Salon.

The possible break-up of the Impressionists that had worried Pissarro showed itself in the sixth and seventh exhibitions with few of the initial contributors putting forward works for inclusion. Pissarro continued to support the Impressionist Exhibitions, refusing to enter works at the Salon and in fact contributed to all eight Impressionist Exhibitions. Times were still difficult for Pissarro and the collapse of the French economy at the start of the 1880’s made it even more difficult for him to sell his work. In 1884 he moved from Pontoise to the small village of Eragny sur Epte which lies north east of Paris. It was whilst living here that he met the artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac and he became a convert to their new approach to art which was known as Neo-Impressionism. I will go more into Neo-Impressionism movement and the related “–isms” of pointillism and divisionism, both of which are relevant to Neo-Impressionism, when I feature the works of George Seurat.

By the time of the eighth and last Impressionist Exhibition in 1886 there was an apparent lack of harmony among the remaining Impressionist artists, and the work of the Neo-Impressionists was shown separately from that of the others. It was noticeable that both Monet and Renoir were absent from this last exhibition. Seurat showed his now famous, and very large work entitled A Sunday on La Grande Jatte which he had just completed and which dominated the room. The room also contained Pissarro’s own Neo-Impressionist submissions which consisted of nine oil paintings, as well as gouaches, pastels, and etchings.

Pissarro’s love affair with Neo-Impressionism was short lived and in 1889 he began to move away from the style, believing that it made it “impossible to be true to my sensations and consequently to render life and movement”. Impressionism at this point in time had run its course. Pissarro carried on painting city scenes although his erstwhile colleagues Renoir, Sisley and Monet had abandoned such subjects. Pissarro completed a number of works featuring the streets of Paris and the Gare Saint Lazare.

In his latter years Pissarro suffered from a recurring eye infection that prevented him from his en plein air work and any outdoor scenes he wanted to paint he did so whilst sitting by windows of hotel rooms he stayed at, always making sure he had a top floor room with a good view. He carried on doing this when he toured around the northern French towns of Rouen, Dieppe and Le Havre and also when he made trips to London. Pissarro died in Paris in 1903, aged 73. He was buried along with the other greats of French art, music and literature in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Camille’s descendents followed his path in the art world. His granddaughter, the daughter of his son Lucien, Orovida Pissarro is a painter in her own right. His great-grandson, Joachim Pissarro, is former Head Curator of Drawing and Painting at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and is now a professor in Hunter College’s Art Department. His great-granddaughter, Lélia, is an artist who lives in London.

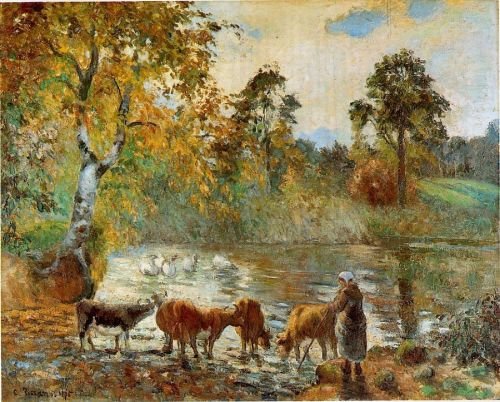

My daily Art Display featured work of art today by Camille Pissaro is a painting he completed in 1875 entitled The Pond at Montfoucault. In 1859, a few years after arriving in Paris, Pissarro, whilst attending the Académie Suisse, met some aspiring artists who would become very famous, such as Monet and Cézanne. He also became great friends with a lesser known painter, Ludovic Piette. Piette often exhibited at the Paris Salon in the 1860’s and also some of his paintings were shown at the Third Impressionist Exhibition of 1877. Piette’s home was in the small village of Montfoucault, which lies on the border between Normandy and Brittany. Pissarro went to stay with Piette on a number of occasions and when the Franco-Prussian war broke out Pissarro and his family left their home and took refuge with Piette before crossing the Channel to England.

It was later in 1874 when Pissarro had come to Montfoucault to try and relax and get over the stress and disappointment of the First Impressionist Exhibition that he started to paint some local country scenes. He especially liked to depict female workers engaged in their daily duties and this is what we see in today’s painting. Before us we see a female herding some cattle by the pond which lay on Piette’s property. Pissarro enjoyed his visits to Montfoucault and he wrote to Theodore Duret, the French journalist, author and art critic about his work but you can sense an uneasiness and doubt in his mind about his art. He wrote:

“…I haven’t worked badly here. I have been tackling figures and animals. I have several genre pictures. I am rather chary about going in for a branch of art in which first-rate artists have so distinguished themselves. It is a very bold thing to do and I am afraid of making a complete failure of it…”

There is a beautiful tranquillity about this painting and one can see how an artist like Pissarro would have liked basing himself in this area.