Van Rysselberghe went to Haarlem in September 1883 to study the light in the works of Frans Hals. He was fascinated by the way the artist had rendered the light and this facet of painting would remain with him for the rest of his life. It was also in the Netherlands that he first met the American painter William Merritt Chase.

Fantasia Araba, by Théo Van Rysselberghe (1884)

Having returned from the Netherlands he remained at home for a short while before setting off on his second painting trip to the Moroccan town of Tangier in November 1883 along with Franz Charlet who had accompanied him on his previous trip. He remained in Morocco for twelve months and managed to put together a large number of paintings and sketches. The highlight of which was his large painting (300 x 170cms) entitled Fantasia Araba, which he completed in 1884. It can be seen at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels.

Even though he was in North Africa Théo remained in close contact with Octave Maus discussing the running of Les XX. Les XX was a group of twenty Belgian painters, designers and sculptors, formed in 1883 by the Brussels lawyer, publisher, and entrepreneur Octave Maus.

Les XX poster for their sixth exhibition in 1889

For ten years, Les XX held an annual exhibition of their art; each year twenty other international artists were also invited to participate in their exhibition. Théo would suggest names of artists to Maus who he believed should be invited to their first exhibition in 1884. In the first year’s show the foreign invitees included Auguste Rodin, John Singer Sargent, Max Liebermann, Whistler and William Merritt Chase

Abraham Sicsu (Consul de Belgique a Tanger) by Théo Van Rysselberghe (1884)

His long stay in North Africa ended in October 1884 when he ran out of money and had to return home to Belgium. Once again he had many completed paintings to exhibit, including Fantasia Araba, at the second Les XX exhibition in 1885. Another of van Rysselberghe’s paintings exhibited was his portrait of Abraham Sicsu who had entered the service of the Belgian legation in Tangier in 1864 as an interpreter. Many famous painters and members of the Belgian royal family had visited him. He was appointed Belgian consul and officer of the Order of Leopold on 8 April 1889 and finally obtained Belgian naturalisation.

Madame Edmond Picard in Her Box at Theatre de la Monnaie by Theo Rysselberghe (1886)

In the 1886 Les XX exhibition van Rysselberghe saw the works of the Impressionist, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. He was so enthralled by what he saw that he decided to experiment with this artistic technique. An example of this is his 1886 painting entitled Madame Edmond Picard in Her Box at Theatre de la Monnaie.

Madame Oscar Ghysbrecht by Théo van Ryssdalberghe (1886)

… and his Portrait of Madame Oscar Ghysbrecht in which he used a palette of bright colours.

Les Dunes du Zwin, Knokke, by Théo van Rysselberghe (1887)

…and the impressionist style of van Rysselberghe carried on through many of his landscape and seascape painting including his 1887 work entitled Les Dunes du Zwin, Knokke, a municipality of of West Flanders in Belgium.

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat (1886)

Van Rysselberghe had cultivated close ties with the Parisian art scene, so much so that Octave Maus asked Rysselberghe to go to Paris and search out up-and-coming new talent who would be able to take part in future exhibitions of Les XX. Whilst in Paris van Rysselberghe became aware of Pointilism, a technique of painting in which small, distinct dots of colour are applied in patterns to form an image. It was a hallmark of Neo-Impressionist painters. Théo first saw it when he visited the eighth impressionism exhibition in 1886 and Georges Seurat’s painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Théo and some other Belgian artists brought the pointillism art form back to Belgium but not every art critic was impressed by this new technique. Seurat was invited to exhibit at the 1887 salon of Les XX in Brussels but it received a very unfavourable reception with many art critics labelling it as “incomprehensible gibberish applied to the noble art of painting”.

Anna Boch by Théo van Rysselberghe (c. 1889)

Not to be deterred by the art critics’ vitriolic comments Théo decided to change his painting style abandoning realism and became proficient at pointillism. In the summer of 1887, he spent a few weeks in Batignolles, near Paris with Eugène Boch, a brother of Anna Boch, a Belgian painter, art collector, and the only female member of the artistic group, Les XX. His 1889 painting of Anna Boch is a good example of Théo’s pointillism style. It was while with Eugène Bloc that he met several painters from the Parisian art scene such as Sisley, Signac, Degas and especially Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. He took the opportunity to invite several of them, including Signac, Forain, and Toulouse-Lautrec to the next exhibition of Les XX.

View of Meknès by Théo van Rysselberghe (1888)

In December 1887 Théo was invited, together with Edmond Picard, to accompany a Belgian economic delegation to Meknès, one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco, located in northern central Morocco and the sixth largest city by population in the kingdom.

Encampment near a Moroccan Village by Théo van Rysselberghe (1888)

Encampment near a Moroccan Village by Théo van Rysselberghe (1888)

His third stay in Morocco lasted three months during which time he completed many coloured pencil sketches, made copious notes and took many photos all of which he used to complete paintings. When he had finished these paintings, he stopped completely with this “Moroccan period” in his life. He now turned to portraiture, resulting in a series of remarkable neo-impressionist portraits.

Portrait of Alice Sèthe by Théo van Rysselberghe (1888)

The portrait of Alice Sèthe was an early one of van Rysselberghe’s divisionist (or pointillist) works which juxtaposes small touches of pure tones on the canvas. Alice stands before us in a beautiful blue and white dress. Behind her are the accoutrements of a luxurious setting. Van Rysselberghe’s mixing of colours no longer takes place on his palette but in the eye of the observer. Théo Van Rysselberghe remains one of the few artists who have put this technique in his portraits. This blue and gold portrait, completed in 1888, would become a turning point in his artistic life.

Portrait of Irma Sèthe by Théo van Rysselberghe (1894)

Gérard Sèthe was a wealthy textile merchant from Brussels who belonged to Van Rysselberghe’s circle of friends. Van Rysselberghe portrayed the Sèthe daughters, Irma, Maria and Alice on several occasions. The portrait of Irma Sèthe depicts her playing the violin. The Sèthe family were very musical with Maria playing the harmonium and Irma was apprenticed to the “King of Violin” Eugène Ysaÿe, a violinist and teacher at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels. The Portrait of Irma Sèthe epitomises Van Rysselberghe’s pointillism. The satin of Irma’s dress lights up in full pink, comprised of thousands of dots of unmixed colours. The changing light and colour effects create a strong plastic effect over the folds on Irma’s sleeves and skirt. In Irma’s portrait we see her completely engrossed in playing her violin. Our eyes are fixed on her and yet, maybe unnoticed at first, we see that she is not alone as sitting in the room next to her is another woman sitting in a chair with one hand laid on her blue dress. Why was this other woman included in the portrait? Is Irma aware of her presence? Only van Rysselberghe knows the answers. The portrait was exhibited in 1895 at the Paris Salon des Indépendants, in 1898 at the salon of La Libre Esthétique, and in 1899 at the thirteenth exhibition of the Vienna Secession.

Marie Monnom by Fernand Khnopff (1887)

Fernand Khnopff completed this Portrait of Marie Monnom in 1887. Her father, a publisher of L’Art moderne in Brussels, had commissioned the work. We see her in Khnopff’s studio sitting in an armchair and seen from the side. It shares a number of elements with several portraits of women painted by Khnopff such as the golden circle on the wall on the upper left, the gloves that Marie is wearing, the framing which slices off the subject’s feet. She does not hold our gaze and her face, although bathed in light, is expressionless. Nothing of her personality shows through.

Sunset at Ambleteuse by Théo van Rysselberghe (1899)

Cap Griz Nez by Théo van Rysselberghe (1900)

On September 16th 1889, Théo van Rysselberghe, a close friend of Khnopff’s, married Marie Monnom and they went on their honeymoon to the south of England and then to Brittany where he made many sketches that he would later turn into finished paintings. In October 1890 their daughter Élisabeth was born.

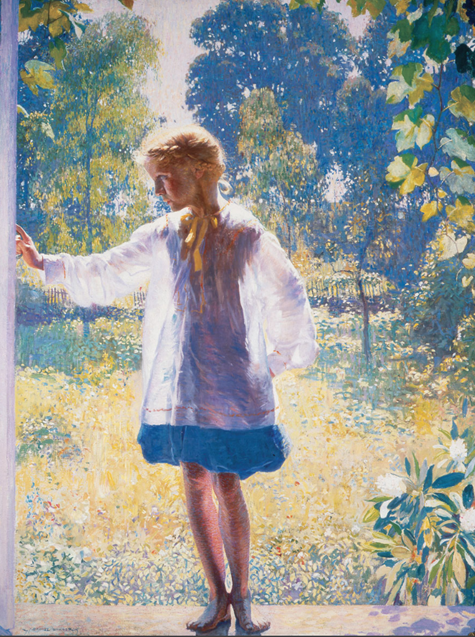

Élisabeth by Théo van Rysselberghe, (1916)

Madame Theo van Rysselberghe and Her Daughter by Théo van Rysselberghe (1899)

Élisabeth in Straw Hat by Théo van Rysselberghe (1901)

Van Rysselberghe’s wife and daughter featured in many of his portraits.

Olive Trees near Nice by Théo van Rysselberghe (1905)

As the years passed van Rysselberghe used his pointillist technique less frequently and by 1910, he had completely put aside pointillism. His brushstrokes became longer and he used more often vivid colours and more intense contrasts, or softened hues. He had mastered the application of light and heat in his paintings.

Female Bathers Under the Pines at Cavaliere by Théo van Rysselberghe (1905)

He completed his painting entitled Olive Trees near Nice in 1905 and the technique he used for this work is similar to one used by Vincent van Gogh with its longer brushstrokes in red and mauve becoming prominent in his 1905 painting, Bathing ladies under the Pine Trees at Cavalière.

The Vines in Saint Clair by Théo van Rysselberghe (1912)

Van Rysselberghe was travelling along the Mediterranean coast with his friend, the French Neo-Impressionist painter, Henri-Edmond Cross, looking for a suitable place to live. Cross lived in Saint-Clair and van Rysselberghe immediately fell in love with this coastal location. Théo’s brother Octave, who lived nearby, was an architect and, in 1911, he built a house for his brother. Théo now living on the Côte d’Azur slowly extricated himself from the Brussels art scene.

Bathers by Théo van Rysselberghe (1920)

The Model’s Siesta by Théo van Rysselberghe (1920)

Nude from behind Fixing her Hair by Théo van Rysselberghe (1920)

Now living on the Mediterranean coast many of Théo’s painting featured nearby landscape and coastal scenes. He continu

ed with his portraiture mainly focusing on his family. However in the first two decades of the twentieth century he produced many works featuring female nudity.

Théophile van Rysselberghe died on December 14th 1926 aged 64 and was buried in the cemetery of Lavandou, next to his friend and painter Henri-Edmond Cross.

Once again most of the information for this blog came from various Wikipedia and associated sites.