Today My Daily Art Display looks again at an artist who many believe was the greatest French painter and the leader and dominant inspiration of the classical tradition in French painting. His name is Nicolas Poussin.

Poussin was born of a noble but impoverished peasant family in Les Andelys, small town in Normandy in 1594. In his youth he studied Latin, and this was to have great influence in his future works of art. In his late teenage years he met an artist, Quentin Vartin, who had come to Les Andelys to carry out a church commission. It was then that Poussin showed the visiting artist some of his artistic work who then agreed to give the youngster some artistic tuition. In 1612 Poussin left Les Andelys and went to Paris and studied art at the studios of the Flemish portrait painter Ferdinand Elle and the French painter George Lallemand. French art and the way it was taught and learnt by young aspiring artists had yet to change and apprenticeships with established artists was still the only way young men would learn to become painters. It would soon change in France when academic training for up and coming artists would supplant this old system. It was not until 1648 that the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was founded by Cardinal Mazarin. The purpose of this academy was to professionalize the artists working for the French court and give them a stamp of approval.

Around 1623 Poussin met Giovanni Battista Marino in Paris. Marino was court poet to Marie de Medici at Lyon. The poet was very impressed with Poussin’s work and urged him to travel to Rome to widen his artistic experience. Poussin had already made two unsuccessful attempts to go to the Eternal City but in 1624, aged thirty, he made it to Rome and initially lodged with the French painter, Simon Vouet. Life in the city proved difficult as Poussin was always short of money. However he was befriended by Cassino dal Pozzo, a wealthy antiquarian and secretary to Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who were both to become Poussin’s earliest patrons. It was in 1628 that Poussin received two major commissions; the first was from Barberini, for a pair of large history paintings, The Death of Germanicus and The Destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem. The paintings were well received. The following year a commission from the Vatican for an altarpiece resulted in The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus which is My Daily Art Display featured painting today. The work was not greeted with universal acclaim in fact it was a comparative failure with the art critics of Rome. It could well have been the fact that Poussin was French and that the Italians did not take to his attempt to compete with the Italian masters of the Baroque style on their own ground. After this Poussin ceased competing for large public commissions and would paint only for private patrons and even then would confine his work to formats which were seldom larger than five feet in length.

In 1630 he became ill. It is believed that he contracted venereal disease. He was taken to the house of his friend Jacques Dughet, whose daughter Anna Maria cared for him. Poussin and Anna Maria married in 1630 but the couple never had any children. Anna’s brother, Gaspard Dughet studied art as a pupil of Poussin and was later to take Poussin’s surname as his own.

By now news of his achievements filtered back to his home country and the court of Louis XIII and the powerful Cardinal Richelieu. He was summoned by the court to return and reluctantly he had to acquiesce to the royal command and in 1640 he returned to Paris. He was offered commissions for types of work he was not used to nor really competent to carry out, including the decoration of the Grande Galérie of the Louvre palace. Worse still, the works he did complete did not bring forth the admiration he had anticipated, so annoyed at the lack of acclaim, he left Paris in 1642 and returned to Rome. Ironically after his death, Poussin’s style of painting was accepted and acknowledged and in the late seventeenth century it was glorified by the French Academy.

Poussin was never a well man and his health started to decline more rapidly when he was in his mid fifties and with it came problems with his hands which suffered from ever worsening tremors. In his later paintings one could detect the unsteadiness of his hand. He died in Rome in 1665 aged seventy-one and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, his wife having predeceased him.

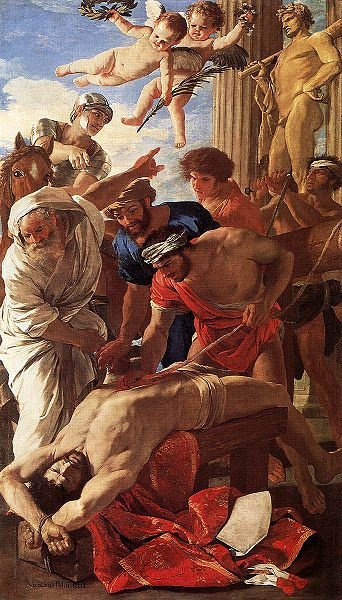

And so to today’s painting, The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, which Poussin completed in 1629. Nicolas Poussin’s altarpiece depicting the Martyrdom of St. Erasmus was commissioned in 1628 for the for the altar of the right transept of Saint Peter’s Basilica, the Chapel of St. Erasmus, in which relics of the Saint are preserved. It was part of the ongoing decoration of the great basilica. The commission had been initially given to Pietro da Cortona but was then assigned to Poussin in 1628 who used the preparatory sketches of Cortona’s as a basis for the work. Poussin was probably obliged to produce not only a preliminary compositional drawing but also a painted modello, a model, to give his patrons a clear idea of his intentions

In the painting of Saint Erasmus, also known by his Italian name, Saint Elmo, we see the subject in the foreground. He was the bishop of Formiae, Campagna, Italy, and suffered martyrdom in 303 AD, during Diocletian’s persecution of the Christians. The setting is a public square. The painting shows the almost naked Erasmus being disembowelled. To the left of him we see a priest dressed in white robes talking to Erasmus and pointing upwards to the statue of Hercules, a pagan idol that Erasmus had refused to worship and which resulted in his martyrdom. In the left mid ground we see a Roman soldier on horseback who is overseeing the execution. It is a horrific and gruesome scene. We see Erasmus’ executioner, dressed in a red loin cloth, extracting the intestines of the martyr who is still alive, and they are being fed on to what looks like the rollers of a ship’s windlass, which is being slowly turned. Above we see two angels descending, one of who is carrying a palm and crown which are the symbols of martyrdom.

The painting remained in the basilica until the eighteenth century at which time it was replaced by a copy in mosaic and the original transferred to the pontifical palace of the Quirinal. It was then taken to Paris in 1797 following the Treaty of Tolentino between France and the Papal States during the French Revolutionary Wars. It returned to Italy in 1820 and it became part of the Vatican Art Collection of Pius VI.

Let me end this blog with two pieces of trivia. When a blue light appears at mastheads of ships before and after a storm, the seamen took it as a sign of Erasmus’s protection. This phenomenon is known as “St. Elmo’s fire”. Erasmus is also appealed to when suffering from stomach cramps and colic. This probably comes about due to the way the saint met his death!

For another of Poussin’s paintings, Rinaldo and Armida, look at my blog of March 8th.