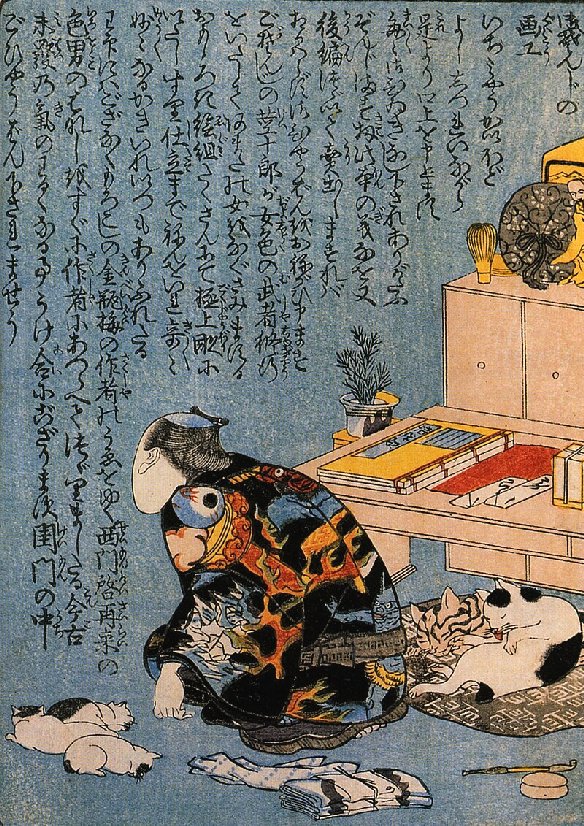

Memorial Portrait of Utagawa Hiroshige by Utagawa Kunisada (c.1858) This portrait of the artist Hiroshige shows him as he looked just before his death, with the robes and shaven head of a Buddhist priest. At the age of sixty, two years before his death of an undetermined long illness, he took monks vows.

Utagawa Hiroshige or Andō Hiroshige, born Andō Tokutarō in 1797 was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition.

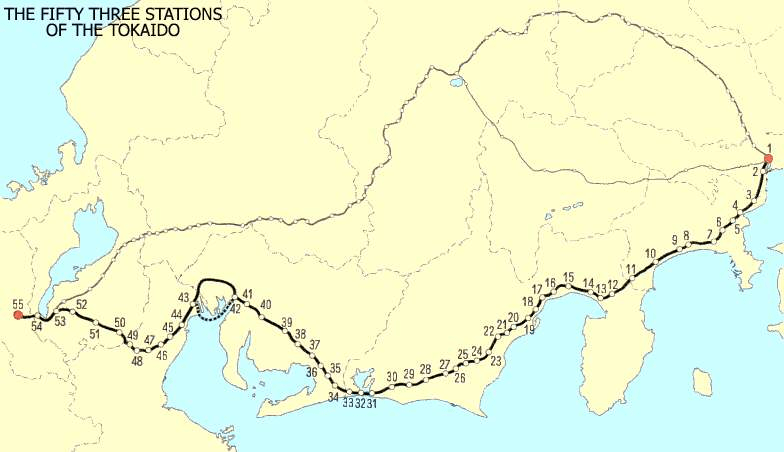

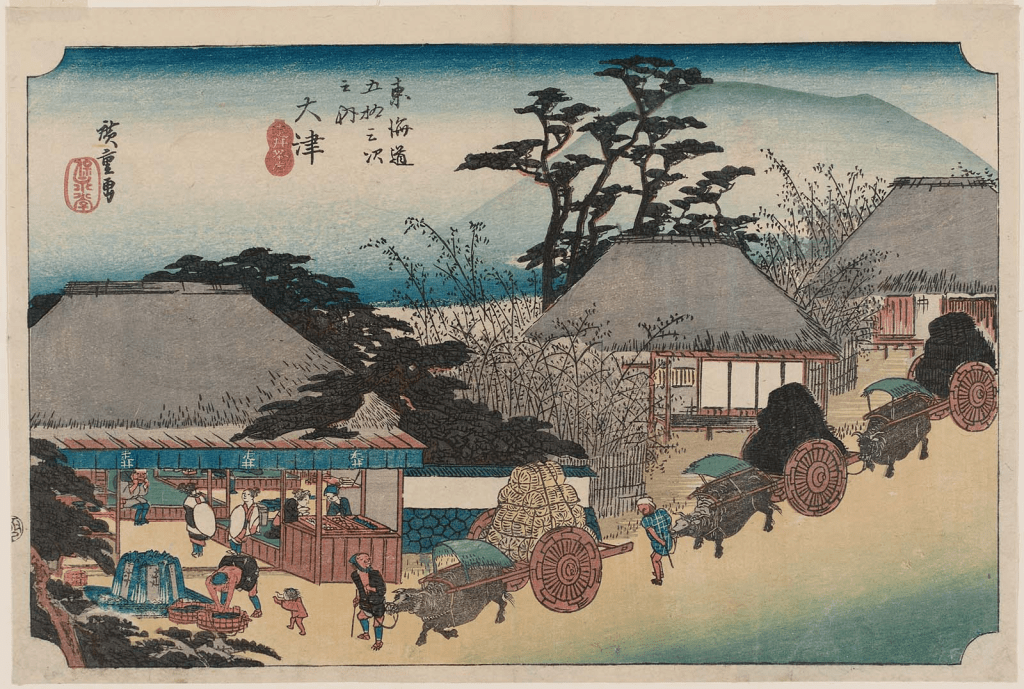

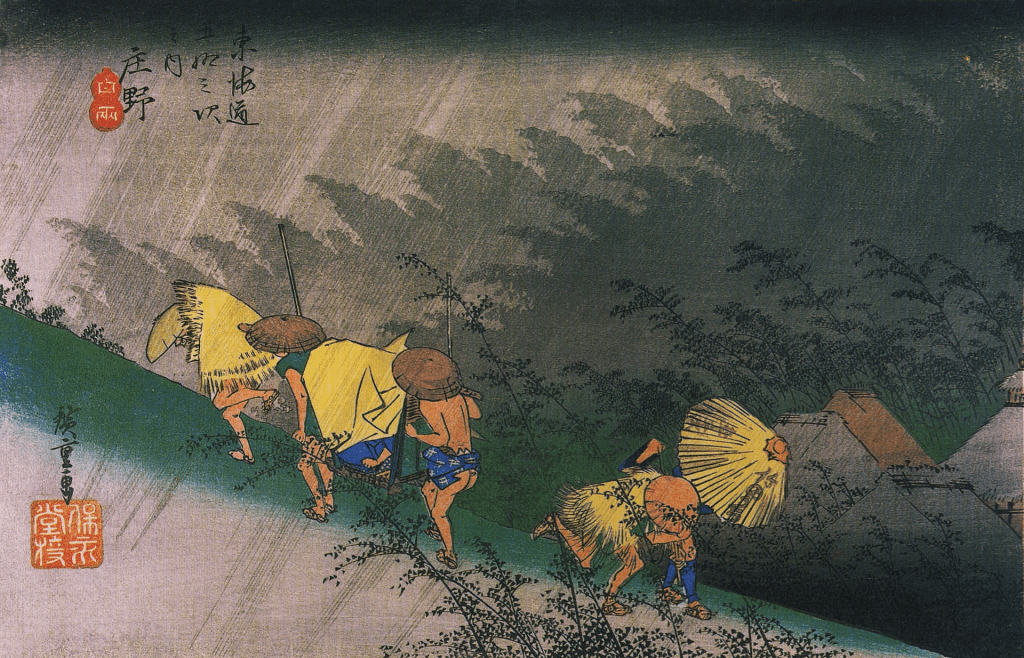

In March 2023 I began a three-blog series looking at his woodcut prints of Hiroshige entitled The Tokaido Road Trip. The Tōkaidō Road, which literally means the Eastern Sea Road, and was once the main road of feudal Japan. It ran for about five hundred kilometres between the old imperial capital of Kyoto, the home of the Japanese Emperor and the country’s de facto capital since 1603, Edo, now known as Tokyo, where the Shogun lived.

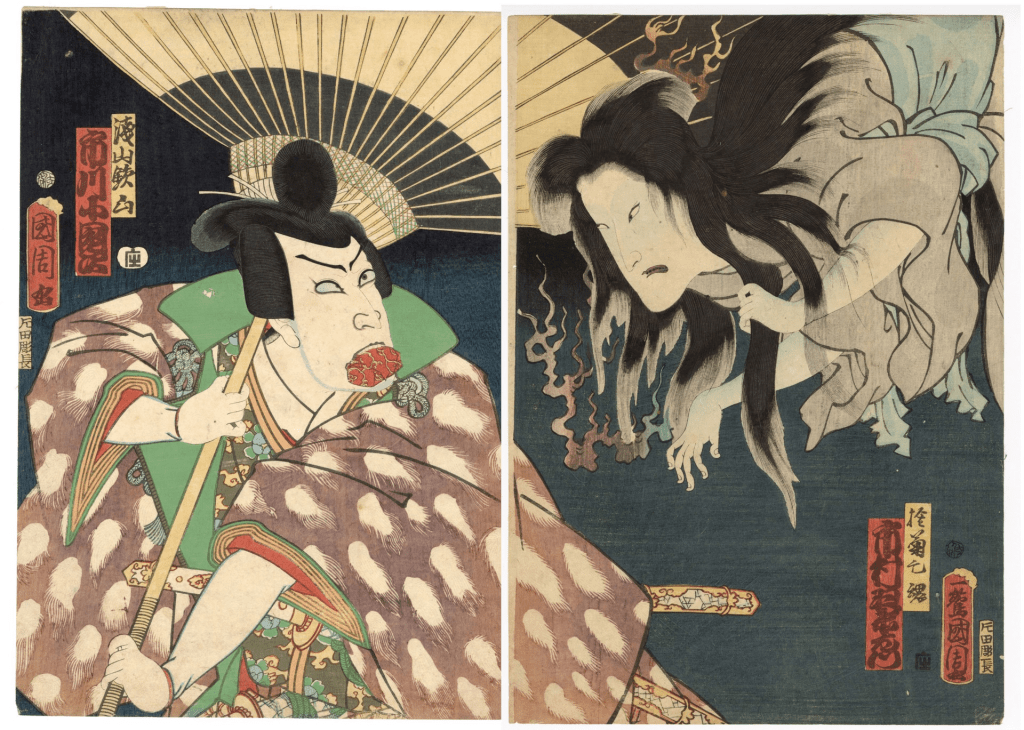

Today I want to start a two-blog series looking at one of Hiroshige’s great print collection series entitled Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces (Rokujuyoshu meisho zue) and whisk you away on a pictorial journey around Japan courtesy of the great Japanese master ukiyo-e print artist, Utagawa Hiroshige. Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica.

Yamashiro Province, The Togetsu Bridge in Arashiyama by Hiroshige. Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series.

Togetsu Bridge

The first print I am offering depicts the Togetsu Bridge which straddles the Katsura River. The 150-metre-long structure has been a landmark in Western Kyoto’s Arashiyama District for over four hundred years. It is known for its natural beauty. Changing colour throughout the year with blushing pink in the spring and ablaze in reds, oranges, and yellows each autumn. The bridge has often been used in historical films. It is also the site of an important initiation for local children. Young boys and girls (the latter clad in kimono) first receive a blessing from a local temple and then make their way across the bridge under orders to do so without looking back. If one ignores this instruction, it is said to bring bad luck as a result, so the stakes are high.

Kawachi Province: Mount Otoko in Hirakata by Hiroshige. Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series.

The series represents a further development of Hiroshige’s landscape print design, including some of his most modern compositions. The striking new use of a vertical format allowed Hiroshige to experiment with the foreground and background contrasts typical of his work, drawing the viewer in while at the same time implying a sense of great distance. In the depiction we see the Yodo River curving below, the rugged peak of Mount Otoko breaks through the clouds. Mount Otoko was home to the Iwashimizu Hachimangu Shrine, one of Japan’s most important Shinto sites and a popular pilgrimage destination. The use of bokashi (color gradation) infuses the scene with a rich atmosphere. Bokashi is the Japanese term which describes a technique used in Japanese woodblock printmaking. It achieves a variation in lightness and darkness (value) of a single colour or multiple colours by hand applying a gradation of ink to a moistened wooden printing block, rather than inking the block uniformly. This hand-application had to be repeated for each sheet of paper that was printed. The best-known examples of bokashi are often seen in 19th-century ukiyo-e works of Hokusai and Hiroshige, in which the fading of Prussian blue dyes in skies and water create an illusion of depth. In later works by Hiroshige, an example of which is the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, most prints originally featured bokashi such as red-to-yellow-to-blue colour sunrises.

Izumi Province, Takashi Beach by Hiroshige. Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series.

Takashi Shrine

The high vantage point of this design allows for a sweeping panorama and an expansive view of the beautiful coastline. In the foreground of this print, nestled amongst the pine trees on the side of a lush green hill, is the Tagashi Shrine, which is nestled among the pine trees and pilgrims follow the track to the holy place. Looking further down the pine-covered slope we can see Osaka Bay which reaches out to the horizon in the background whilst waves can be seen crashing onto Takashi Beach. Hiroshige used the technique known as kimetsubushi to enhance the colours. Kimetsubushi was a technique used to enhance the expressive application of colours in woodblock printing and involved the intentional use of woodgrain (visible in traditional printing blocks, which were cut parallel to the grain of the tree). Called kimetsubushi (“uniform grain printing”), the process involved working the surface of the wood with stiff brushes or rubbing with pads to roughen the surface and thereby impress the paper with the grain pattern in areas of relatively uniform or “flat” colour.

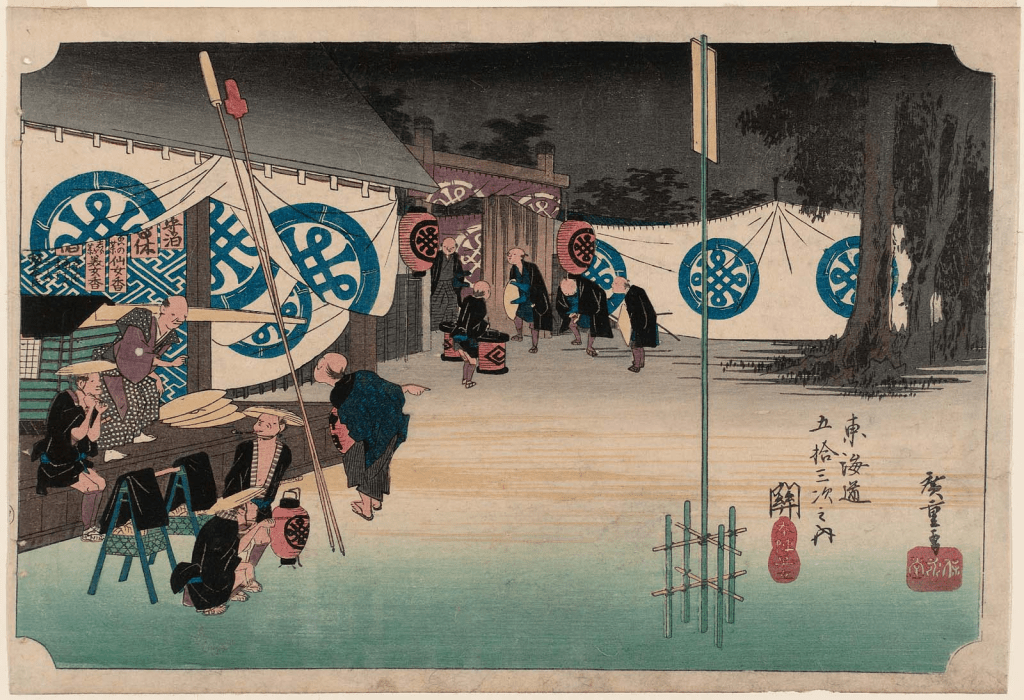

Owari Province, Tsushima, Tenno Festival by Hiroshige. Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series.

Festival Owari Tsushima Tenno

Festival Owari Tsushima Tenno

The setting of this print is the Tenno River and we see from above, as night begins to fall over the mountains and hills, the river is illuminated by the hundreds of lanterns decorating the boats which are part of the Tenno Festival. The festival, which has existed for more than five hundred years, is held on the fourteenth and fifteenth days of the sixth month on the lunar calendar and the highlight of the celebration is the sailing of the illuminated boats. It is one of the three major river festivals in Japan and nationally renowned. To cater for the crowds visiting the festival, temporary teahouses have sprung up on the riverbank.

Sagami Province, Enoshima, The Entrance to the Caves by Hiroshige Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series.

On the left edge of the print we can just see the side of Mount Fuji. In the foreground waves can be seen crashing against the rugged cliffs of Enoshima, a small offshore island, about 4 km in circumference, Below the lush green of the cliffs above, the cave entrance in the lower right temps the viewer into the darkness of the cave. Hewn by the waves over time, this cave system housed a shrine to Benzaiten, a goddess associated with fortune and artistic success. The caves attracted many pilgrims, and the entire island was considered a sacred site. In addition to the usual travellers, this small island attracted many celebrities and ambitious individuals.

Pilgrimage to the Cave Shrine of Benzaiten by Hiroshige (c. 1850)

Three year before Hiroshige embarked on his Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series he completed another woodcut print of Cave Shrine of Benzaiten at Enoshima.

Hida Province, Basket Ferry by Hiroshige Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series.

Detai; of Hida Province Basket Ferry

The Basket Ferry (detail) by Hiroshige

The Hida Province, Basket Ferry is illustrated in one of Hiroshige’s woodcut prints. Travellers are ferried above a swift flowing river using an ingenious rope and basket system which is fixed between two sheer cliffs. In the depiction we see the jagged cliffs rise up all around as the sun sets behind the mountain range beyond. It is a beautifully coloured print which once again is detailed with fine bokashi shading. It is not thought that Hiroshige ever tried this “ferry” but it is more likely that he found these details in the designs of others, perhaps an illustration by his teacher Utagawa Toyohiro in his 1809 novel The Legend of the Floating Peony.

Shinano Province, The Moon Reflected in the Sarashina Paddy-fields, Mount Kyodai by Hiroshige. Print from Hiroshige’s Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces series

As clouds encircle the base of Mount Kyodai reflections of the full moon seem to leap through the paddy-fields, each watery surface reflecting its likeness in this atmospheric composition. The Just above the fields, Choraku Temple sits in the shadow of “Granny Rock.” This place is also significant in that it was the location of the signing of the Treaty of Shimoda in 1855, which officially established diplomatic relations between Bakumatsu Japan, the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended, and the Russian Empire.

………to be continued.

Apart from various Wikipedia sites the information for this blog came from:

ISSUU – Hiroshige: Famous Places in the 60-odd Provinces -Ronin Gallery