Balke returned to Christiania in 1830 and stayed with Professor Rathke and in that May travelled to Copenhagen and was fortunate to be able to view royal collections of art. Of all the works he saw, Balke was most impressed by a winter landscape painted by Johan Christian Dahl, entitled Winter Landscape. Near Vordingborg, which he completed in 1827. The large (173 x 205cms) work of art depicts a somewhat oppressive atmosphere with its undertones of death, symbolised by the dolmen behind the lifeless branches of the two oak trees. A dolmen is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright stones supporting a large flat horizontal capstone. Nature is depicted in the form of its icy winter garb. He wrote of the painting to Rathke saying that it was the most life-like painting he had ever seen. The fact that he had managed to see the works of the great Masters at the royal collection, although influencing him, also depressed him somewhat as to his own ability. He wrote:

“…I sometimes felt a certain heaviness of heart and lack of courage when I compared my own insignificance with these true masterpieces; quietly and I admit somewhat superficially I calculated how much I would have to learn and how many ordeals I would have to go through before I would be able to achieve a mere fraction of the perfection in aptitude and skill in execution exuded by these paintings…”

Balke was determined to succeed and in the summer of 1830 having returned to Norway from Copenhagen he set off on foot on an artistic journey through the Telemark region and over the mountains to western Norway and then north to Bergen returning to Christiania via the Naeroydalen valley and the town of Gudvangen. He later recalled his short time spent in the area around Gudvangen, writing:

“.. I first arrived late at night, because I became so engrossed in admiring the sublime beauty of Naeroydalen that I hardly knew whether what surrounded me was real or supernatural. So fascinating and uplifting did my youthful imagination, with its passion for the beauties of nature….”

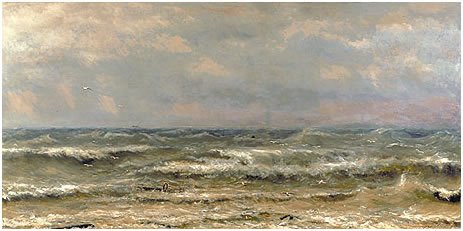

Two years later, in April 1832, Balke set off another artistic journey. This time, setting off in his own carriage he went to Trondheim where he was to catch a boat to the north of the country. His planned journey hit a snag when he arrived late in Trondheim and missed the boat. He had to wait a further seven weeks for the next boat but spent the time sketching the town and the surrounding areas. Peder Balke finally embarked on his northbound boat trip, passing the Lofoten Islands and arrived at Tromso. From there the boat went further north to Hammerfest and then proceeded around the North Cape to Vardø and Vadsø. He was the first Norwegian painter to record the harsh beauty of the northern landscape. Eventually Balke and the boat returned to Trondheim. During the long journey Balke had completed a large collection of sketches of the places he had seen and many were used in his many seascape and moonscape works of art which he worked on when he returned to Stockholm. He sold many of his paintings to wealthy Norwegians and Swedes as well as members of the royal family. In 1834, now, financially secure, Peder married Karen Eriksdatter, the woman he had been secretly engaged to for several years, but had been too poor to marry.

The couple settled in Christiania and Balke, now accepted, not simply as a decorator but as a landscape artist, tried to establish himself and sell his artworks. However competition at the time was too great and the sales he had hoped for never materialised. However, in 1835, he managed to sell another of his works to the king and with that money he decided on fulfilling his dream of travelling to Dresden and work with the Norwegian artist, J C Dahl. Many Norwegian artists had trodden this path, including Thomas Fearnley (see My Daily Art Display November 24th & 28th 2012). With help from a friend, Balke set off for Germany and reached Berlin in the winter of that year. He remained in Berlin for several weeks and was able to visit the Royal Museum and whilst in the German city he saw paintings by the German romantic landscape painter, Casper David Friedrich. It was this artist who was going to have a great and lasting influence on Balke.

Balke left Berlin and travelled to Dresden via Leipzig. He received a great welcome from Johan Dahl who helped him find accommodation. J C Dahl introduced Balke to Casper David Friedrich and Balke was able to watch the two great artists at work. In a letter to Rathke, dated March 29th 1836, he wrote about watching J C Dahl at work:

“..to see Dahl paint, I know with which colours and have seen how he uses them, and though I at present cannot proceed successfully in the same manner I hope that with time I will also reap the benefit. What I regret most is my lack of studies from nature. Dahl certainly has several thousands of them, of all kinds. He has told me there is no other way to become a real painter than by painting from nature, which admittedly has been my intention, and I shall now try to see whether I can make up for what I have hitherto neglected, in Norway, though not in Germany – there is no nature here…”

Balke left Dresden but returned in the 1840’s to work once again with J C Dahl. Landscape art was popular in Norway and Balke managed to sell many of his works but things were to change when a number of young Norwegian landscape artists having returned from studying at the Dusseldorf Academy, which at the time was looked upon as the most modern art-educational institute. The teaching of landscape art was more to do with what was termed “cautious Realism” rather than Balke’s Romantic landscapes which suddenly became less fashionable. He had to endure much criticism with regards his work which had once been loved by his people. In an article in a 1944 edition of Morgenbladet, the eminent art critic Emil Tidemand scathingly wrote about Balke’s paintings:

“… There is no question here of a grandiose, poetic perception: no not even the simplest technical demands of drawing, perspective, clarity, strength and depth of colour have been met……………….This is not a representation of nature – his whole production is merely the mark of a dirty palette handled without discrimination…”

Maybe it was the vitriolic criticism which made Balke realise that there would be no hope of becoming financially secure through his art sales in Norway and so in 1844 he, along with his pregnant wife and three young children, left their homeland and travelled to Paris via Copenhagen and Germany There was also another reason to visit Paris and this was that Balke was well aware that the country’s ruler Louis-Philippe had, as a young prince in exile in 1795, travelled along the Norwegian coast from Trondheim to the North Cape just as he had done. As Balke did not speak French he asked a friend to write a letter on his behalf to the king in which he reminded the king of his exile and his Norwegian journey and that his nine sketches of the area would remind the king of that journey. Louis-Philippe was intrigued and summoned Balke to the palace. Balke and the king immediately became close and the two would meet regularly and reminisce about their travels to the North Cape

Louis-Philippe commissioned a set of paintings derived from the sketches. Balke’s financial future seemed to have been rescued and he set to work on the commission. Alas fate was to take a hand in the form of the February Revolution of 1848 which saw the downfall of Louis-Philippe. Balke realising the dangers of being close to the unpopular ruler decided in late 1847 that he and his family would have to hurriedly leave Paris which meant he had to abandon, what was to have been a very lucrative commission. Balke moved back to Dresden. Shortly after his arrival in the German city in 1848 his young son Johann died. His death came around the same time that his wife gave birth to their daughter Frederikke. Sales of his art in Dresden were hard to come by and so he decided to leave his family with a friend and head back to Christiania. He managed to sell some of his work, one of which was The North Cape by Moonlight but still the Norwegian people favoured the Dusseldorf School of landscape painting and so Balke returned to his family in Dresden. In the Spring of 1849 he and his family moved to London where Balke believed his art would be more appreciated. London had fallen under the spell of Joseph Mallord William Turner and his marine paintings and so Balke believed his works of art would do well. He was proved right and managed to sell more of his works of art.

1860-70

In the autumn of 1850 Balke and his family moved back to Christiania. In 1855 his good friend and benefactor Professor Rathke died and left Balke a sizeable amount of money which Balke used to buy eight acres of land just outside the city limits at a place known as Vestre Aker. He virtually abandoned his career as an artist of large scale landscape works, concentrating on small scale paintings which he believed would be bought by the middle class. He now concentrated on his property portfolio and in particular the development of housing for workers in his newly attained property in the suburb of Balkeby, He dabbled in local politics championing the cause of pensions for men and women, and also of grants for artists. His painting was now just a hobby and for his own pleasure.

Balke, as you may realise, was an unlucky man and more bad luck came in June 1879 when his beloved Balkeby went up in flames. Nearly every house, including his own, was burnt to the ground. Four years later Balke suffered a stroke, and he died in Christiania on February 15th 1887 aged 82. The obituaries that followed after his death were all about his political work and little was said about Balke the artist. Maybe his penchant for ignoring criticism and sticking to what he believed in was apparent in the obituary which appeared in the magazine Verdens Gang in March 1887. It emphasised Balke’s pugnacity:

“…Fearless and straightforward as he was, it would never occur to him to defer to people in an argument. He considered only the matter in hand and did not bother in the least about who was for or against him. This does not always result in popularity…”

I can recommend an excellent book about the artist and his work entitled Paintings by Peder Balke, from which I derived most of my information about this Norwegian painter.