When I visited the Claude Lorrain exhibition at the Ashmoleon Museum in Oxford last month, I had time to look around their permanent collection of painting. To my mind they have one of the best collections on offer with works from artists of different nationalities and from different eras. I strongly recommend you visit this gallery for I know you will not be disappointed.

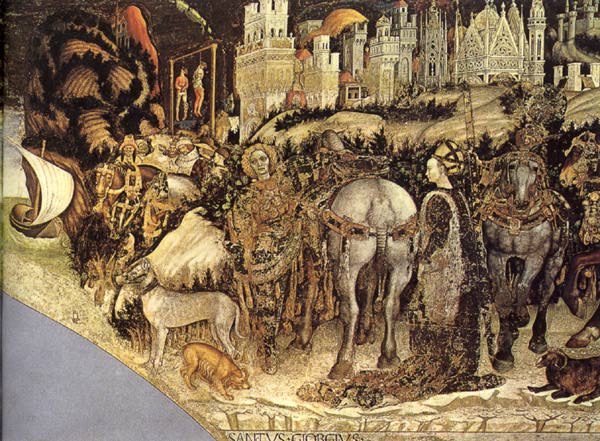

The painting I am featuring in today’s My Daily Art Display is one by Paolo Uccello entitled The Hunt in the Forest which he completed around 1470. Hunting was a very popular pastime for the aristocracy in those days. The depiction of hunting in art goes back to the Ancient Greeks when it can be seen on their tableware. During the time of the Romans, many hunting scenes can be found on their sarcophagi and in Medieval times hunting scenes could be found in their manuscripts, wall paintings and tapestries. There were many forms of hunting in the Medieval times, such as hunting with hawks, which took place mainly in the spring and summer and the boar and bear hunting which took place during winter.

It is believed that this work of art you see before you was a one-off painting and not part of a series. It is of an unusual size, measuring 63cms tall x 165cms wide. With those dimensions it could well have been intended for the front panel of a cassone, a Renaissance marriage chest or a spalliera, the back of a Tuscan bench or settle, or the headboard or footboard of a bed. The spalliera paintings were very popular at the time this painting was completed. Therefore we are probably safe to assume that this work was painted for a wealthy family to be seen by guests as they entered the house and went into the camera, the reception room which was also often the bedroom, where the spalliera or cassone would be in pride of place.

So what do we see before us? Is it a painting of a real hunt or is it an imaginary scene? Art historians tend to believe the latter is correct as hunts such as these would have had a number of different species of dogs each trained to carry out a specific task in the hunt. There would be dogs which were good at following scents. There would be another species of dog which were fast running and capable of catching and bringing their quarry to ground. In this painting we only have the one type of dog. In the painting we also only see one type of deer, the roebuck, and that would be unlikely to be the case in a real hunt. The setting for the hunt is also very questionable. The scene is dark and it appears that the hunt is taking place at twilight or during the night and this is not the normal time of day set aside for hunting. Hunting, especially in forests, would normally take place during the day when the maximum amount of sunlight can filter through the trees.

The view we have before us is also one of organised chaos ! The hunters seem to be converging upon each other from two sides while the dogs and the hunted animals seem to be disappearing into the central distance. There seems to be no attempt by the hunters to enact a carefully co-ordinated plan to capture their prey.

I love the vibrant colours in this painting. Look how Uccello has given the leaves on the trees golden highlights. I love the bright livery of the horses and the colourful clothing of the aristocratic hunters atop their horses, ably being assisted by the beaters. On the livery of the horses we see many examples of a golden crescent moon emblem which could be a sort of homage to Diana the Roman goddess of hunting (Artemis the Greek goddess of hunting) who was often seen wearing a crown shaped as a crescent moon.

The aristocracy liked to have hunting scenes adorning the walls of their mansions. Hunting, in some way, like chivalric jousting tournaments, was akin to battle and those taking part in such events were looked upon as being fearless and athletic. Men who organised such hunts (maybe not in this case!) were looked upon as being tactically astute and great leaders and just the qualities which were needed for those who were to lead armies into battle. In those days hunting was a very prestigious pastime and strangely, sometimes looked upon as an allegory of love.

The one question, which has yet to be answered and one can only guess at it, is who commissioned Uccello to carry out this work. We know that this was Uccello’s last major painting before he died in Florence in 1475 and historians think the painting was completed around about 1470. Art historians have come up with a couple of ideas but none our conclusive. I have already mentioned the crescent moon emblems on the horses livery and as well as being associated with Diana they were also the emblem of the Strozzi family. The Strozzi clan were an ancient and noble Florentine family who played an important part in the public life of Florence and this painting may have been commissioned by one of them. The other possibility was that Uccello painted this picture whilst he was still living in Urbino and before he returned to Florence. We know that he was in Urbino from 1465 to 1469 and if that was the case he could well have been commissioned by his patron, the Duke of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro whose palace was full of works of art.

This is undoubtedly a masterpiece and as we look at the painting we can almost hear the noise made by the hunters crashing through the undergrowth and the baying of their animals as they chase after their unfortunate quarry. It is an exciting painting full of vitality and colour. The artist encourages us to stare into the depth of the forest and our eyes alight on Uccello’s distant vanishing point in the central background but no sooner do we stare into the distance than our eyes dart back to the foreground, seduced by the colours and the rhythm of the hunt.

I just love this work and it is even better to stand in front of the original.