In my last blog I looked at The Raising of Lazarus by Sebastiano del Piombo and talked about how this and a painting by Raphael, entitled Transfiguration, had been commissioned in 1517 by Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici as a high end altarpiece for the French Cathedral of S. Giusto Narbonne. Raphael was, at the time, busy on other commissions. He had been summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II to paint frescoes on the rooms of his private Vatican apartment, the Stanza della Segnatura and the Stanza di Eliodor and at the same time he was busy working on portraits and altarpieces as well as working alongside Sebastiano del Piombo on frescoes for Agostino Chigi’s Villa Farnesina. It is thought that Giulio de Medici was so concerned with the time it was taking Raphael to complete The Transfiguration altarpiece that he commissioned Sebastiano di Piombo to paint the Raising of Lazarus for the cathedral in an effort to stimulate Raphael to work faster on his commission.

Today I am featuring Raphael’s work, The Transfiguration, which was considered the last painting by the Italian High Renaissance master. Giorgio Vasari, the sixteenth century Italian painter, writer, historian, and who is famous today for his biographies of Renaissance artists, called Raphael a mortal God and of today’s painting, he described it as:

“…the most famous, the most beautiful and most divine…”

Although Raphael Sanzio was only thirty-four years of age when he was given the commission, bad health prevented him from finishing it. It was left unfinished by Raphael, and is believed to have been completed by his pupils, Giulio Romano and Giovanni Francesco Penni, shortly after his death on Good Friday 1520.

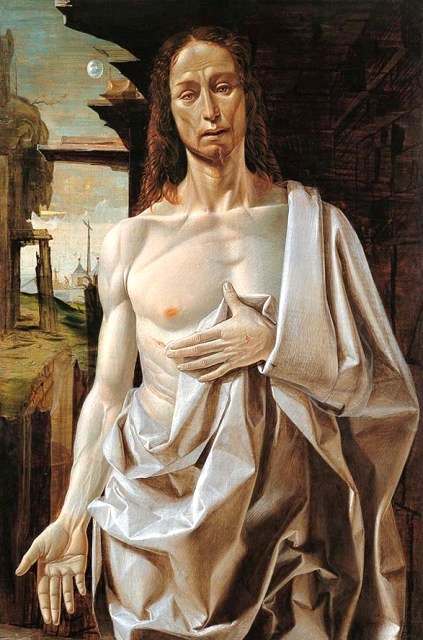

If we look closely at this work of art we can see two things going on simultaneously both of which are described in successive episodes of the Gospel of Matthew. In the upper part of the painting we have the Transfiguration, which is described in Matthew’s Gospel (Matthew 17: 1-7):

“…After six days Jesus took with him Peter, James and John the brother of James, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light. Just then there appeared before them Moses and Elijah, talking with Jesus. Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good for us to be here. If you wish, I will put up three shelters—one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, a bright cloud covered them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell facedown to the ground, terrified. But Jesus came and touched them. “Get up,” he said. “Don’t be afraid…”

We see the transfigured Christ floating aloft, bathed in a blue/white aura of light and clouds. To his left and right are the figures of the prophets, Moses and Elijah. Below Christ we see the three disciples on the mountain top shielding their eyes from the radiance and maybe because of their own fear of what is happening above them. The two figures kneeling to the left of the mountain top are said to be the martyrs Saint Felicissimus and Saint Agapitus of Palestrina.

In the lower part of the painting we have a depiction by Raphael of the Apostles trying, with little success, to liberate the possessed boy from his demonic possession. The Apostles fail in their attempts to save the ailing child until the recently-transfigured Christ arrives and performs a miracle. Matthew’s Gospel (Mathew 17:14-21) recounts the happening:

“…When they came to the crowd, a man approached Jesus and knelt before him. “Lord, have mercy on my son,” he said. “He has seizures and is suffering greatly. He often falls into the fire or into the water. I brought him to your disciples, but they could not heal him.” “You unbelieving and perverse generation,” Jesus replied, “how long shall I stay with you? How long shall I put up with you? Bring the boy here to me.” Jesus rebuked the demon, and it came out of the boy, and he was healed at that moment. Then the disciples came to Jesus in private and asked, “Why couldn’t we drive it out?” He replied, “Because you have so little faith. Truly I tell you, if you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move. Nothing will be impossible for you…”

Observe this lower scene. The young boy, with arms outstretched and distorted in a combination of fear and pain, is possessed by some sort of demonic spirit. He is being led forward by his elders towards Christ who is about to descend from the mountain. The boy is crying and rolling his eyes heavenwards. His body is contorted as he is unable to control his movement. The old man behind the boy struggles to control him. The old man, with his wrinkled brow has his eyes wide open in fear as to what is happening to his young charge. He looks directly at the Apostles, visually pleading with them to help the young boy. See how Raphael has depicted the boy’s naked upper body. We can see the pain the boy is enduring in the way the artist has portrayed the pale colour of his flesh, and his veins, as he makes those violent and fearsome gestures. The raised arms of the people below pointing to Christ, who is descending, links the two stories within the painting. A woman in the central foreground of the painting kneels before the Apostles. She points to the boy in desperation, pleading with them to help alleviate his suffering.

The contorted poses of some of the figures at the bottom of the painting along with the torsion of the woman in what Vasari calls a contrapposto pose were in some way precursors to the Mannerist style that would follow after Raphael’s death. Vasari believed that this woman was the focal point of the painting. She has her back to us. She kneels in a twisted contrapposto pose. Her right knee is thrust forward whilst she thrusts her right shoulder back. Her left knee is positioned slightly behind the right and her left shoulder forward. Thus her arms are directed to the right whilst her face and gaze are turned to the left. Raphael gives her skin and drapery much cooler tones than those he uses for the figures in heavy chiaroscuro in the lower scene and by doing so illuminates her pink garment. The way he paints her garment puts emphasis on her pose. She and her clothes are brilliantly illuminated so that they almost shine as bright as the robes of the transfigured Christ and the two Old Testament Prophets who accompany him. There is an element about her depiction which seems to isolate from the others in the crowd at the lower part of the painting and this makes her stand out more.

The unfinished painting was hung over the couch in Raphael’s studio in the Borgo district of Rome for a couple of days while he was lying in state, and when his body was taken for its burial, the picture was carried by its side. Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici kept the painting for himself, rather than send it to Narbonne and it was placed above Raphael’s tomb in the Pantheon. In 1523, three years after the death of Raphael, the cardinal donated the painting to the church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome. In 1797, following the end of the war in which Napoleon’s Revolutionary French defeated the Papal States; a Treaty of Tolentino was signed. By the terms of this treaty, a number of artistic treasures, including Raphael’s Transfiguration, were confiscated from the Vatican by the victorious French. Over a hundred paintings and other works of art were moved to the Louvre in Paris. The French commissioners reserved the right to enter any building, public, religious or private, to make their choice and assessment of what was to be taken back to France. This part of the treaty was extended to apply to all of Italy in 1798 by treaties with other Italian states. It was not until 1815, after the fall of Napoleon, that the painting was returned to Rome. It then became part of the Pinacoteca Vaticana of Pius VII where it remains today.