Cyril Mann – the early years and Canada.

No man succeeds without a good woman behind him. Wife or mother, if it is both, he is twice blessed indeed.

Harold MacMillan

In many of my blogs I have related the story of a husband and wife who had both been artists but after the marriage and after the birth of the children one has had to give up their career as an artist to look after their spouse and children and that caring role always seems to land at the feet of the wife, who then dedicates her life to her artist husband or partner. The next few blogs are going to look at the lives of a great British artist and the support and love he received from his young wife which allowed him to become a well-known painter. This is not simply a tale about an artist, it is about the resilience of his young wife and how she battled his moods and supported him through times of his severe depression. Please settle back and join me as I explore the lives of the English artist Cyril Mann and his beautiful young wife, Renske.

My earliest self-portrait by Cyril Mann (1937)

To start this journey, one must look at Cyril’s upbringing and, as one knows, a person is often affected or moulded by their early life experiences. Cyril’s father was William Aloysius Mann who was brought up in a reputable middle-class Nottingham family environment. He was the third child of four, having an elder sister and brother, Annie and Will and a younger brother Austen. Like most parents Cyril’s grandparents were hopeful that their four children would make good in life. Their aspirations for Cyril’s father turned to despair when the only job he could secure was one of a bricklayer, which they considered to be a menial profession and somewhat below the family’s social status. If that was not bad enough, Cyril’s father became romantically entangled with a local working-class woman, Gertrude Nellie Burrows, whom his parents believed was not good enough for their son. In a pointed slight to her, they would refer to her as Gertie, when she was better known as Nellie.

William and Gertrude Mann’s circumstances became worse when he became unemployed and so, to seek work, the family left Nottingham and moved to London. Their son Cyril was born in Paddington, London on May 28th 1911. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 William Mann was conscripted into the army and was shipped off to fight on the Western Front. In 1918, after many years of witnessing the horrors of war, he was honourably discharged as “shell shocked”.

Saxondale Psychiatric Hospital

The war had taken the toll on William’s mental health and he would never be the same again. On returning to civilian life, the family returned to Nottingham and William was committed to the Saxondale Hospital in Sneiton, the city’s psychiatric hospital. Cyril’s father would remain there until his death in 1938 but during his twenty years of incarceration he would make a number of escapes !

Times were hard for Gertrude who had to try and survive on her husband’s small war pension and bring up four children. Unlike her husband who had been lazy, untrustworthy and very often easily distracted, his wife was the total opposite. She was resilient, down-to-earth and strongminded when it came to bringing up her young family. One does not know for sure how the children were affected by the family circumstances but going on public transport to collect their father from the asylum for his home leave on public holidays must have affected them psychologically.

The children did survive their early childhood. Cyril’s brothers Austen and Will proved to be musical with Austen winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Music but never got to go there as he was diagnosed as being partially deaf. Cyril’s father, before going off to war, was also musical and had been an accomplished violinist. Cyril’s paternal grandfather had been a talented amateur artist who had had his work exhibited at the Nottingham Castle Art Museum. Cyril developed his own artistic flair when young and was always top in his art class at school. He was so talented that at the age of twelve, he won an art scholarship to Nottingham School of Art and his mother had to get special dispensation to take him out of regular school as he was under fourteen years of age.

One of Constant Troyon’s paintings featuring cattle (Pastoral Scene c.1860)

In later years Cyril talked about his early interest in art and how he had been impressed at seeing one of Constant Troyon’s paintings of cattle.

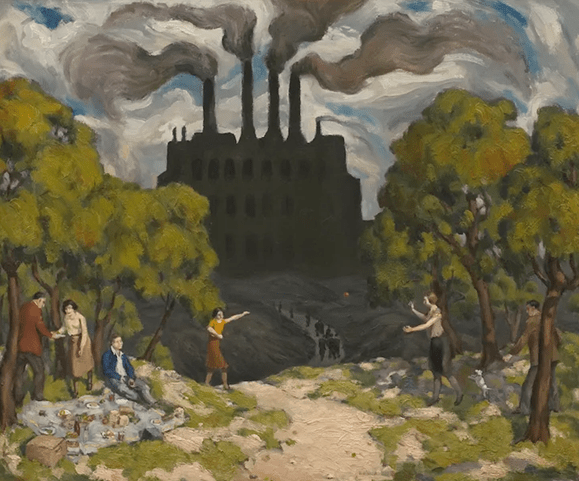

Dark Satanic Mills by Cyril Mann (1925)

One of Cyril’s early paintings that still exists is entitled Dark Satanic Mills which he completed in 1925, when he was just fourteen years of age. The painting depicts a park in the foreground and a dark threatening-looking factory in the background with thick black smoke issuing from its chimneys. In the midground we see figures enjoying park life. It is an extraordinary landscape work for someone so young. Cyril’s mother needed financial support from her children to supplement her husband’s pension and so she had to withdraw Cyril from the Art College and install him in a paying-job that would bolster the household finances. Cyril must have been upset at being taken away from the art school but took an exam to join Boots the Chemist as a clerk. He failed and this must have come as a surprise to his mother as her son had always excelled at regular school and one has to wonder whether Cyril had deliberately failed as he hated the thought of a job as a clerk when he wanted to continue with his art. However, and probably much to his annoyance, he did eventually work as a clerk until he was sixteen.

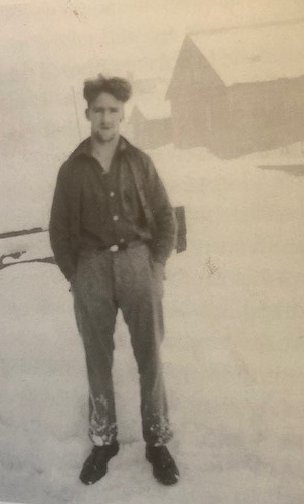

Sixteen-year-old Cyril Mann prior to moving to Canada (c.1927)

In 1927, aged sixteen, Cyril’s life changed. His mother Nellie had always been a religious person and had insisted that her children attended the High Anglican Church and Cyril, for a time, was an altar boy. In a way, and in the mind of his mother, this churchgoing brought to the family an air of respectability and sophistication and, in her mind, it was a way to gain social progression and an elevated status. Cyril at this time became very friendly with a local priest who offered to accompany him to Canada, all expenses paid, so that he may “enter” the church and become a young missionary.

Fishermen, Canada by Cyril Mann (1929)

It took little time for young Cyril to acquiesce to the priest’s request. It was probably a combination of the thought of adventure similar to what he had seen in the Boy’s Own Paper, youthful religious zeal and the thought of freeing himself from his controlling mother. Having reached Canada, it was not long before Cyril began to question his decision about serving God as a missionary and he and the priest parted company.

Eighteen-year-old Cyril Mann in Canada (Winter 1929)

Cyril then tried out many jobs – a miner, a logger, a travelling salesman and ended up as a printer in British Columbia on the Canadian side of the Alaskan border.

Cyril Mann, artist at work in Canada (c.1930)

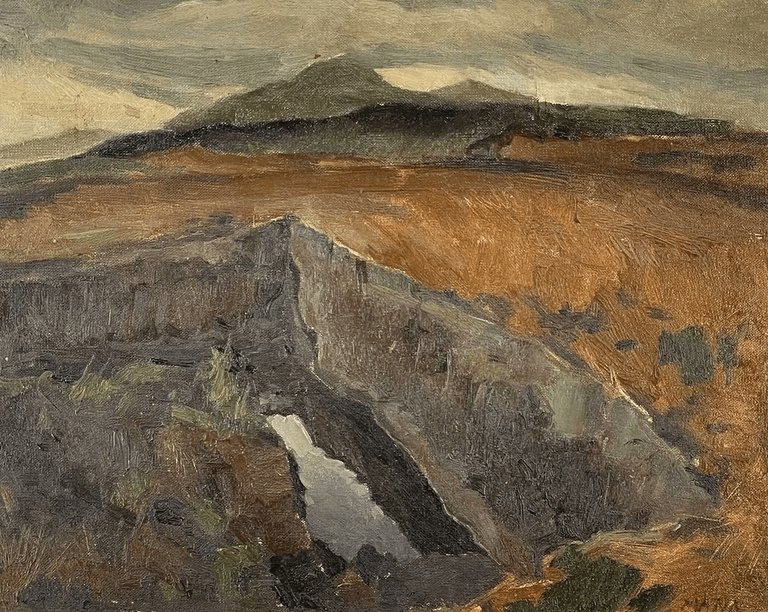

He was now living in the midst of beautifully spectacular landscapes – a landscape artist’s paradise, and soon he began to sketch and paint the breathtaking views.

Canada- Mountainscape by Cyril Mann (c.1931)

Panning for Gold by Cyril Mann (c.1929)

In Canada at that time, the prevailing influence in Canadian art was the artwork of the Group of Seven. The Group of Seven also known as the Algonquin School was a group of Canadian landscape painters from 1920 to 1933. The original members were Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J. E. H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley. They believed that a distinct Canadian art could be developed through direct contact with nature, the Group is best known for its paintings inspired by the Canadian landscape and they initiated the first major Canadian national art movement. Their artwork was highly colourful and often depicted Autumn and Winter scenes, and they believed that the power of the light from the sun was to be recorded in their work.

Six of the Group of Seven, plus their friend Barker Fairley, in 1920. From left to right: Frederick Varley, A. Y. Jackson, Lawren Harris, Barker Fairley, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, and J. E. H. MacDonald. It was taken at The Arts and Letters Club of Toronto.

Cyril Mann was impressed and influenced by the work of the Group of Seven along wth one of their associates, Tom Thomson and in 1932 he visited a Group of Seven exhibition in Vancouver and met one of the group, Arthur Lismer who was then working as a lecturer.

Old Pine, McGregor Bay by Arthur Lismer (c.1929)

Arthur Lismer had been born in Sheffield, England in 1885 and had emigrated to Canada in 1911. Lismer advised Cyril that if he wanted to become a professional artist he should return to England and access the best artistic tuition available, Cyril saw the sense in the advice and in early 1933 he returned to his homeland.

A Mann family outing in Skegness. Cyril on the far right whilst his mother Gertrude is in the middle, Cyril’s older sister Annie is second from the left next to her husband. The other two men are thought to be Gertrude’s brother Austen on her left and Cyril’s younger brother Austen wearing the white clothes. on her right.

Nottingham Houses by Cyril Mann (c.1933) Cyril has depicted his mother tending the garden

After landing in England, he travelled to the family home in Nottingham. To his surprise he wasn’t greeted with a hearty welcome from his mother, instead she was very critical about his physical appearance. Cyril was both upset and very annoyed by his mother’s authoritarian manner which he had had to endure through childhood and, there and then, decided his future home would not be with his family in Nottingham but instead he would head south to the English capital.

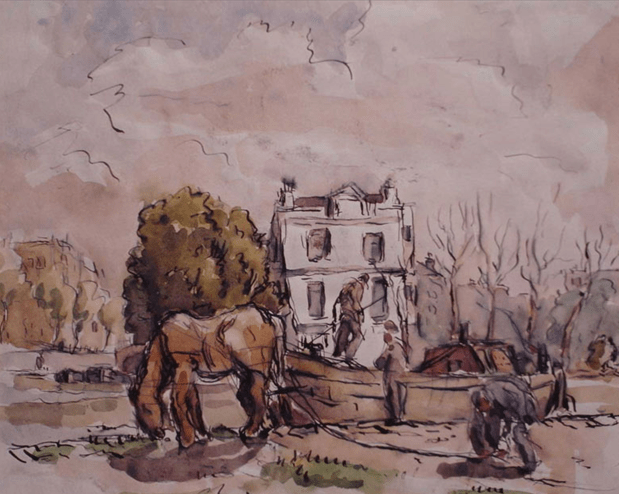

Maida Vale Canal by Cyril Mann (c.1934)

Arriving in London in 1933, during the Great Depression, Cyril the young aspiring artist, despite finding it impossible to find a job carried on with his watercolour painting depicting various loacations around Paddington and around the Little Venice canal in Maida Vale, while he he took time off from his paintingnto to join the ever-lengthening dole queues. He found and rented a cheap apartment in Paddington, close to where he was born, and endured the degradation of poor living standards and little money for sustenance. With not having employment he had plenty of free time which he partly filled with painting local scenes using watercolours. Having left school at the age of twelve he realised he had missed a lot and he now developed an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. He was a regular visitor at the local libraries and was always willing to engage in conversation with those he encountered so that his knowledge of the world would be broadened and because of his current circumstances, he soon gained an interest in left-wing politics.

Mountain Landscape by Cyril Mann

Having said this, Cyril never joined any official political group but a group he did join was the Toc H Group. The Toc H Group was an international Christian movement whose name was derived from Talbot House, a soldiers’ rest and recreation centre at Poperinghe, Belgium. Its aim was to promote Christianity and look after young soldiers who were returning to civilian life. Each branch of the Toc H had a chaplain to look after the spiritual needs of its members. During the Depression Toc H looked after the many civilians hit by unemployment and, as one of the many people without a job, Cyril came to be one of those who regularly met at the Paddington Toc H in a canal boatmen’s’ club room. Here he could talk to people, which must have been a Godsend for the young man who was out of work and lived alone. The new young chaplain who arrived at the Paddington Toc H in 1935 was Oliver Fielding Clarke, known to everybody as “Bernie”. The chairman of the association asked Clarke to keep a close eye on Cyril, whom he described as “out of work, practically a communist and sometimes pretty blunt with others”. Shortly after receiving that “task” Clarke met Cyril and was completely captivated by the young aspiring painter. In Clarke’s 1970 autobiography Unfinished Conflict, he remembers his conversations with Cyril Mann:

“…I have had many friends and a good deal of the first part of my ministry was given to young men, but few if any of them did more for me than Cyril. We would spend hours and hours together in the evenings and he never spared himself for me. In the early days he had been a [alter] server so that he was not in the least awed by parsons and he also knew how to challenge, or perhaps blister is a more accurate word, a parson’s conscience. I used to get back to Liddon House in the small hours of the morning feeling almost as if we had been engaged in physical combat. Cyril pulverised capitalism and the Church for being its running- dog. He tore to shreds any suggestions that milk-and-water Christian Socialism was the answer and we argued hotly about the existence of God and the nature of morality… All this was interspersed by talk about his art, when he would show me what he had been drawing or painting and what he was looking for as an artist….Both of us thoroughly enjoyed those long evenings; but they did not work in the way that had been expected. Cyril did not move further away from Communism nor nearer to the Church. Instead, I became more and more critical of the Church and increasingly convinced of the truth contained in the teachings of Karl Marx…”

St Pauls by Cyril Mann

It is quite clear from this description that Cyril Mann was an outspoken person with strongly held views which he stuck to notwithstanding the views of others. It is also obvious he had a great self-belief but it could be levied against him that he was aggressively antagonistic to those who did not share his views and it was this latter characteristic which would become a problem for him in later life.

Despite their fiery discussions and the intransigence of Cyril, Bernie Clarke did not give up on him and decided to call in favours from friends in order to get Cyril into employment. The chairman of the Paddington branch of the Toc H arranged for a place at the Royal Academy Schools be made available to Cyril and a friend of Clarke, the twenty-five-year-old daughter of a rich German businessman, Erica Marx, who was a poet, philanthropist and loved art saw the artistic potential of Cyril and set up a trust fund for him to finance his time at the art school. She would remain a lifelong friend and supporter of his and would often buy his paintings.

Dahlias by Cyril Mann

The first half of the 1930s had been a rollercoaster ride for Cyril Mann. Out of work unable to feed himself and yet came through it all and entered the Royal Academy Schools in the Autumn of 1935. The lives of his family back in Nottingham had also been a rollercoaster ride caused by tragedy. Cyril’s elder brother Will died in a lift accident in the Midland hotel in Nottingham where he worked and his younger brother Austen drowned in a river whilst out swimming. His death was witnessed by his wife and two young children who thought his violent thrashing in the water was him playing.

In 1935, now at the Royal Academy Schools, Cyril Mann had taken the first step in becoming a professional artist.

……….to be continued

It would not have been possible for me to put together this and following blogs about the artist, Cyril Mann, without information gleaned from a number of sources:

The comprehensive biography of Cyril Mann, The Sun is God by John Russell Taylor

Renske Mann with her book The Girl in the Green Jumper, My life with the artist Cyril Mann.

This intimate autobiography of her life with Cyril Mann by his second wife Renske, entitled The Girl in the Green Jumpe was a beautifully written story of her life and love for her husnband.

This autobiography has now been turned into a play which receives its World Premiere on Wednesday March 13th at the Playground Theatre, London, 8 Latimer Rd, London W10 6RQU.

The Piano Nobile, a London art gallery which was established by Dr Robert Travers in 1985. The gallery plays an active role in the market for twentieth-century British and international art and has held exhibitions of Cyril Mann’s art.

Finally, and most importantly, I owe many thanks to Renske Mann herself who provided me with information and photographs appertaining to herself and her late husband Cyril.