If you were to decide to hang another picture on one of your walls of your abode, I wonder what you would decide to display. I wonder how you would come to your decision. Would you hang a picture of somewhere you have just visited as an aide-mémoire of the place you enjoyed so much for its beauty, whether it is a seascape, landscape or even a cityscape? Maybe you would consider hanging a print of a painting by one of the great Masters of the Renaissance so that you can be reminded of their artistic mastery but, if you do that, maybe such an inclusion would be construed by your friends as a sign of your pretentiousness. On the other hand, you may choose to hang a painting which, through its complexity and symbolism, becomes a talking point for all those who cast their eyes upon it. Let me offer you an alternative. Today I am featuring a very popular English artist, whose work you either love or hate. She became well-known for her much-adored colourful and ostentatious depictions of large, often scantily-dressed women with a lust for life, often in a setting of a pub or club. She was often referred to as the woman who painted fat ladies. However many were critical of her work. The English art critic, Brian Sewell, was openly disparaging of her artistic style and said of it:

“…very successful formula which fools are prepared to buy but doesn’t have the intellectual honesty of an inn sign for the Pig and Whistle. It has a kind of vulgar streak which has nothing to do with art…”

However, the one thing that her work guarantees is that it will bring a smile to your face and her paintings and prints have sold across the world. The artistic establishment has shunned her work and strangely enough it seems that she understood their condemnation of her efforts as an artist, once saying:

“…I know there are some artists who look down on my work and when you compare mine with some of the others, I can see what they’re getting at…”

At the start even she had been disappointed with what she produced, confessing:

“…I expected to paint like Stanley Spencer. It was a great disappointment to me when I realised that I didn’t…”

The featured painter today was a wonderful proponent of Naive Art, which is a classification of art that is often characterized by a childlike simplicity in its subject matter and technique. So who was this enigmatic and talented person?

Beryl Frances Lansley was born in September 1926 in Egham, Surrey. She was one of four sisters. Her father was an engineer and her mother was an office worker. Her parents’ marriage broke down and her father left the family home when Beryl was just four years old. In 1930, her mother took her and her three sisters to live in Reading where the family was supported by their paternal grandfather. When Beryl was ten years old the Cook family moved next door and they had a son, John, and soon Beryl and John became good friends. Beryl attended the Kendrick Girls’ School in Reading, but in 1940, aged 14, she left school to train as a typist. It should be noted that during her early life and her school days Beryl showed no interest in art!

In 1944 the family moved to Marylebone, London and Beryl took up a number of jobs; as a secretary in an insurance office but she didn’t enjoy office work, as a show girl in a touring production of The Gypsy Princess, but felt too self-conscious to enjoy the experience and in the fashion industry for Goldberg’s of Bond Street, which aroused her life-long fascination with the way people look and dress. In 1947 the family moved once again and this time went to live in an idyllic house in Hampton, a small town on the north bank of the River Thames and it was from their house that Beryl helped her mother to run a small tea-garden. It was around this time that she became re-acquainted with her erstwhile next-door neighbour, John Cook, who during the war had been an officer in the Merchant Navy. Friendship turned to love and Beryl and John were married in October 1948. In 1950 the couple had a son, also called John and in 1952 they all move into John’s mother’s house in Southend-on-Sea, where they remained until they bought their own house in nearby Leigh-on-Sea, Essex the following year.

Her husband left the merchant Navy in 1955 and he and Beryl tried their hand at running a pub and bought the public-house tenancy of the White Horse Inn, in the small village of Stoke by Nayland, on the Essex-Suffolk border. However they had always enjoyed the bustle of city life and were not use to the tranquillity of the countryside that now surrounded them. It what not what they wanted and so they terminated their pub venture after just twelve months. In 1956, John managed to find himself a job with a motor company as a car salesman but the position meant re-locating his family to Salisbury, the capital of Southern Rhodesia. Beryl worked as a book-keeper in an insurance office but she was far from happy with life in Africa and once talked of her unhappy experience in Southern Rhodesia and the ex-pat lifestyle, saying:

“…I didn’t like being so far from the sea and I couldn’t bear the social life which revolved around parties because there wasn’t anything else to do…”

However there was one incident during their stay in Rhodesia that was to change Beryl’s life. It happened in 1960, when her son John was ten years old. She was trying to interest him in drawing and painting and had caught the artistic bug herself, so much so that her husband bought her a set of oil paints. Beryl’s first painting was a half-length copy of a dark-skinned lady which she saw in a photograph, who had large pendulous breasts. Her husband was amused by what he saw and cheekily christened it The Hangover. She never sold this work and remained in the family home.

In 1963 the family moved to the Ndola Copper Belt in Northern Rhodesia. John continued his work as a car salesman and Beryl worked in a finance office. Life for the Cook family was no better, in fact it was worse and they only remained there until 1965. Beryl and her husband had had enough of land-locked Rhodesia and decided to head back home. In 1965 Beryl along with her husband and son returned to the UK settling first in a cottage in East Looe, Cornwall and the change of country and her happiness to be back “home” inspired Beryl to once again take up her art. In 1968 the Cooks moved to Plymouth where they bought a guesthouse on Plymouth Hoe. John Cook continued working in the motor trade whilst Beryl opened up the guesthouse to visitors in the summer. Many of her guests were actors with travelling repertory companies who were appearing at the local theatres. Once the summer was over, the guesthouse was closed and Beryl was able to concentrate on her paintings. She would often use wood instead of canvas and would search for ideal pieces she could find, such as lavatory seats, driftwood and wardrobe doors! She painted continuously during the cold winter months and admitted that she was pleased when summer arrived and she had to put her paint brushes away so as to concentrate on her paying guests. She commented:

“…I had to stop painting for about four months each summer when the visitors were here, and in a way this was quite a relief for by this time there were so many paintings it had become increasingly difficult to stack them!…”

Beryl loved living in Plymouth for it was a flourishing seaside town full of lively and often risqué bars. It was a place frequented by all kinds of people. There were the local fishermen and sailors from the naval warships tied up in the harbour. The place was awash with countless fascinating individuals, and Beryl and her husband would spend time in the local bars where the entertainment was often glitzy and gaudy drag acts. Beryl would often surreptitiously sketch the characters frequenting the bars and they would become the leading figures in many of her paintings.

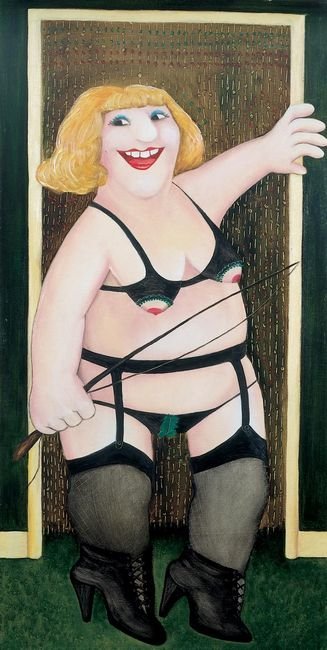

Beryl sold her first paintings in the early 1970’s. The sale of some of her work was arranged by Tony Martin, an antiques dealer friend of the couple, who had bought Beryl and John’s cottage in East Looe. The more her work sold the more she grew in confidence and soon the walls of her guesthouse were filled with her work. In 1972 Beryl asked her husband what he would like for Christmas and his request was simple – he wanted Beryl to paint him a risqué depiction of a scantily-dressed plump young lady. Beryl acquiesced to his Christmas request and gave him a painting which became known as Anybody for a Whipping?

Her paintings were about people and she was surrounded with all types, both locals and holiday makers. A classic work of hers around this time was her hexagonal painting entitled Sabotage, completed in 1975. Three women taking part in bowling are depicted in the work. One very large woman is seen bending over about to bowl whilst one of her fellow bowlers, looks out at us with a cheeky smile, as she pokes the bottom of her compatriot. Beryl painted it on a wooden bread board.

Beryl achieved another artistic breakthrough in 1975 when an actress who was a regular guest at Beryl’s guesthouse and who loved her paintings, which adorned the walls, mentioned them to Bernard Samuels who ran the Plymouth Art Centre. Eventually, after much persuasion, he went to see her artwork for himself. At this time she had about sixty paintings spread throughout the rooms of her establishment and Samuels convinced her that she should exhibit them all together in one room at his Art Centre. The exhibition was held in the November and December of that year and it proved a great success. The number of visitors surpassed all expectations, so much so that the duration of the exhibition was extended.

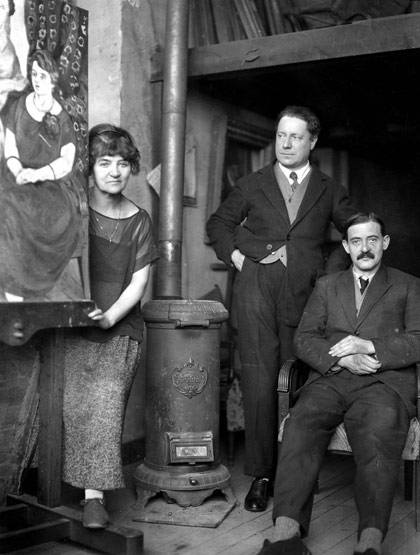

courtesy PWDRO, copyright Plymouth Library Services,

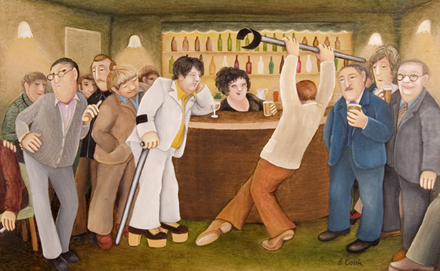

The following year The Sunday Times colour magazine featured one of her works, the Lockyer Street Tavern, with the headline The Paintings of a Seaside Landlady. The Lockyer Tavern on Lockyer Street, Plymouth was built in 1862 but now no longer exists, having been demolished in the late 1970’s. It was a favourite haunt of Beryl and her husband and in the painting we see some of her distinctive characters – the regular pub goers lounging at the bar with their pints of beer and glasses of wine.

There is an effeminate air about some of the characters depicted which probably alluded to a thriving gay community in the seaport at the time. During the 1950s, 60s and 70s The Lockyer Tavern became famous for being a safe place for gay men to drink and socialise, particularly in its ‘Back Bar’. Homosexuality in those days was a taboo subject and The Lockyer became so famous for the sexuality of some of its clientele that it became a coded term for discovering a person’s sexuality – by asking ‘do you know the Lockyer’s? What Beryl was good at was her power of observation and her attention to detail. In this painting we see how she has portrayed the clothing, accessories and hairstyles of her characters. For many the essence of her work is the “fun factor” and how her sense of humour oozes from most of her work. In this painting our eyes are drawn to the falling man who crutch is thrown upwards as he falls as well as the somewhat effeminate pose of the bespectacled man as he disdainfully looks on.

Another Plymouth drinking establishment that featured in many of her works was The Dolphin Hotel. In her 1995 painting entitled Hen Night we see a line of “larger than life” happy ladies entering the establishment with just one thought in their mind – to have a good time. This, for one of them, is her last night of freedom before she gets married. The dress code of the ladies is probably inappropriate for their figures but today it is still the same. They are probably oblivious of how they look in their short skirts and shorts and are just out to enjoy themselves, which I am sure they do. Beryl described the painting:

“…The friends make the bride a hat (in this case a large cardboard box covered in silver paper and saucy decorations) and there is much singing and hooting as they go through the streets…”

Her paintings are all about having a good time and maybe that is why they are so popular as they are amusing and they lift our spirits. In her work entitled Striptease we see men standing around a bar with pints of beer grasped tightly in their hands ogling a larger than life woman as she disrobes in front of them. One can almost imagine the conversation passing between them as the ladies clothes fall, one by one, to the floor.

In 1976 Beryl Cook had her first London exhibition, it was a sell-out. Following this an article appeared in The Sunday Times, and this led to Beryl being contacted by Lionel Levy of the Portal Gallery in London who wanted to put on an exhibition of her work. She agreed, and in 1977 had her first solo exhibition. Following the success of the exhibition she went on to hold annual exhibitions at the portal Gallery for the next eighteen years. Her last one there was in 2006 with the aptly named title Beryl Cook at 80.

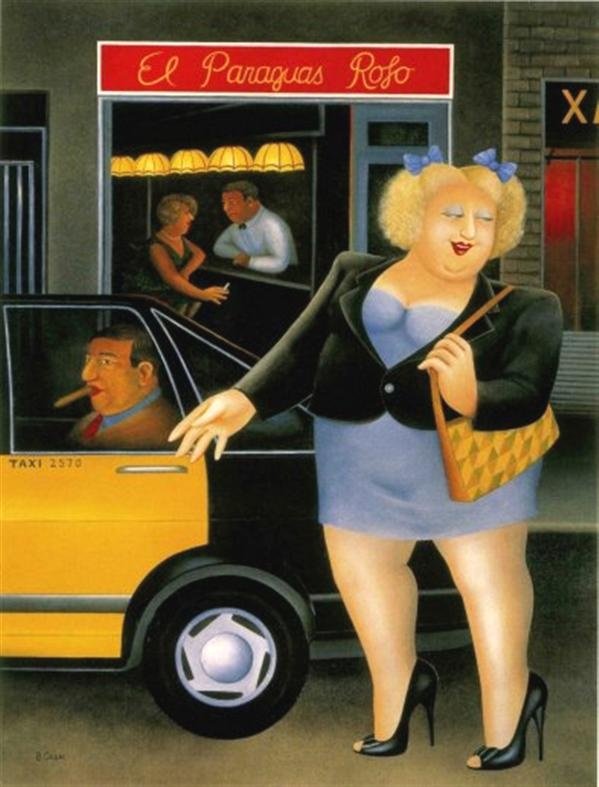

Her paintings were not solely based on what she witnessed during her life in England. She had been an admirer of the works of English painter Edward Burra, who was best known for his often salacious depictions of the urban underworld and black culture. He had painted scenes around the dockside bars of Marseille and the seedier side of the night clubs around Barcelona’s Ramblas district. The works had seduced Beryl and John to visit those places for themselves and for Beryl it was an ideal opportunity to sample the life of these somewhat seedy parts of the towns. From her visit to Barcelona came her painting entitled Red Umbrella which depicted a well-known lady of the night doing her nightly round of the Ramblas bars in search of business.

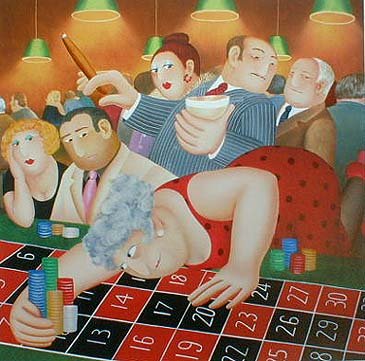

Beryl often derided the ostentatious and one of my favourites is her work entitled Roulette which depicts a room in a gambling establishment. How many times have we, after a few too many drinks, decided that we should end the night at a casino. The outcome is a foregone conclusion with the casino quickly relieving us of our money. In this work we see a plump lady lying across the beige of the roulette table lovingly grasping a mound of chips. Has she just won them or is she trying to place them on her favourite number? The pin-stripe suited man with glass a champagne in one hand and a large cigar in the other passes behind her but leans back as he seems unable to take his eyes off her large derriere. A couple of fellow roulette players sit at the table mesmerised by the lady’s actions.

Beryl Cook was awarded the OBE for services to art in 1966. Many of her works have been bought by British galleries and the Portal Gallery in London has represented Beryl’s work for more than thirty years. In January 2004 her larger than life, over-exuberant characters starred in a two-part animated television series made for the BBC. The animated films, which won several animation awards, was entitled Bosom Pals and Beryl’s voluptuous ladies were transferred from canvas to screen. Besides the recognisable females which were seen in the film the setting used was often The Dolphin pub on Plymouth’s Barbican, which had featured in many of her paintings. People who watched the TV series, and who had never previously seen her artwork, suddenly became aware of talent.

Beryl Cook died in May 2008, aged 81. Her husband of almost sixty years and their son survived her. Beryl Cook never trained professionally, but her paintings have appealed to many for their candour, loudness, and some would say their vulgarity. Her paintings, which often focused on women with large bottoms and bosoms, were as saucy as the well-loved British seaside postcard and they are now looked upon in some quarters as true folk art in the same tradition as Brueghel, Stanley Spencer and the Colombian artist, whom I featured in my last blog, Fernando Botero.