In my last blog I looked at the early life of the German Expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. I left off the biography at the time he decided to leave Dresden and move to Berlin. He was still a member of Die Brücke art group, which he had helped to form, and life for Kirchner was good. Alas, as we all know only too well, life is not constantly good and to our liking and in this second and final instalment of Kirchner’s life I look at what went wrong.

In 1906, Die Brücke held its first exhibition, and two new artists, Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein, joined the group. The following year, one of their founder members, Fritz Bleyl married and left the group to concentrate on looking after his family. In 1908 Pechstein moved to Berlin and in October 1911, Kirchner followed, along with some of the other artists from the group. It was in Berlin that Kirchner along with Pechstein founded a private art school, known as the MIUM-Institut, (Moderner Unterricht in Malerei-Institute). Kirchner’s aim for this private school was to spread the word about modern ways of teaching art. Alas, the venture failed with only two candidates, friends of Kirchner, enrolling on the first course. The school closed the following year. It was in this same year, 1912, that Kirchner met and started a relationship with Erna Schilling, a relationship which would endure all his life.

With all groups of artists, there comes a time when they begin to drift apart, because of their differing views of the future. In cases of musicial groups one of them often wants to pursue a solo career and in the case of artist groups sometimes one of them wants to stage a solo exhibition of their work. With all groups of artists, whether it is painters or musicians, there is often a hierarchical dilemma. Is there to be a leader of the group? Is the group to be run on a consensual basis? This was the problem with Die Brücke as Kirchner believed he was the leader of the group and in 1913 he wrote the Chronik der Brücke, chronicling the history and aims of the group. In his summation of what had gone before he portrayed himself as the leader and thinker of the group and the others were his followers and this upset the other members. This publication along with the desire of some of the members, including Kirchner himself, to do their “own thing” led to the break-up of Die Brücke. Probably because of what Kirchner had written in the chronicle the break-up was not an amicable one and harsh words were exchanged. For Kirchner the split had been so acrimonious that he completely disassociated himself from Die Brücke artists for the rest of his life and would in later years denigrate the work of the group saying the paintings he did during Die Brücke days were simply “the nonsense of youth”. Kirchner was determined that history should remember him and his art as a personal triumph, that he was self-sufficient and in fact, never needed Die Brücke.

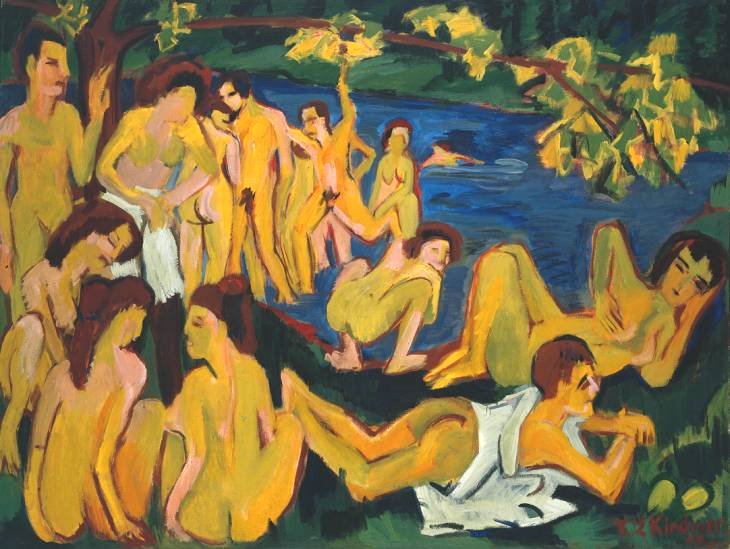

An Artists’ Group by Kirchner (1927)

An Artists’ Group by Kirchner (1927)

The one time, in later years, when he reflected on his Die Brücke days, was in 1926 when he completed a large panel painting entitled An Artists’ Group, which depicted Otto Mueller seated reading the infamous Chronik der Brücke whilst Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff stood to the right discussing this very chronicle, which ironically contributed to splitting the group asunder. Otto Mueller who had only joined Die Brücke in its latter days was included in the work because he was a particular friend of Kirchner but Kirchner pointedly omitted Max Pechstein from the depiction, as he was the least popular member and he had left the group in 1912.

The year 1914 signalled the start of the First World War and this was to have a terrible and deep impact on Kirchner. He received his call-up papers and joined the German army as an “unwilling volunteer” and was posted to Halle where he served as a driver in the artillery in order to avoid being drafted for less desirable duties. Life in the army proved too much for Kirchner and he suffered a series of physical ailments, due to general weakness and lung problems. He eventually suffered a mental breakdown which resulted in him being temporarily discharged from army and confined to a number of sanatoria. Was he ill or did he just want to be away from army life and the horrors of war? Maybe we will never know but during his time in hospital and sanatoria he was able to produce some of his best works including my featured painting today, Self-Portrait as a Soldier.

Kirchner’s mental state showed no sign of improvement and his friends decided that he should move to a more tranquil environment and so they helped him emigrate to Switzerland and the small mountain town of Frauenkirche which lay just below the Stafelalp, just south of Davos. Here he remained for most of his life. It was during these latter years that although his artistic style remained the same, the subjects of his art changed and he took a keen interest in the life of the farmers, who worked in this mountainous region, and he recorded it in some of his works. Although Kirchner was now living in a tranquil setting and his lifestyle was much more relaxed, he was suffering from his time in the various German hospitals and had developed an addiction to drugs and this was exacerbated further by his alcoholism. It was not until 1921 that he managed to wean himself off this narcotic addiction and get his life back together.

During the mid 1920’s Kirchner visited Germany in an attempt to regain recognition for his artistic works. He received a number of commissions and in 1927 he had hoped to be appointed a professor at the Kunstakademie in Dresden. In 1931 he was admitted to the Preussische Akademie der Künste in Berlin and by now most of the major museums in Germany housed some of his artworks. Things were once again looking up for Kirchner but all that was to end two years later in 1933 when the National Socialists came to power. Four years later, in 1937, the National Socialists campaign, known as entartete Kunst (degenerate art), stripped all the museums of his art and he was forced to resign from the Akademie in Berlin. This proved all too much for Kirchner who had returned to his home in Frauenkirch, where on June 15th 1938, aged 58, he stood before his small house and shot himself.

The work I have featured today is the oil on canvas painting, entitled Self-Portrait as a Soldier, which he completed in 1915 and now hangs in the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College in Ohio. In it Kirchner imagines that due to the savagery of war, his hand has been severed and he is unable to paint. Could it be that Kirchner was thinking about Van Gogh’s 1889 painting, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear when he first set about this work, albeit Kirchner’s severed hand was simply in his mind whereas Van Gogh’s self-mutilation was very real?

The work is all about Kirchner’s fears with regards how the war would affect him as an artist. His fear was such that it was almost a pathological fear as to what would happen to him and his life as an artist. It was not just about him but his belief that all young artists would be adversely damaged both mentally and physically by the conflict. Kirchner painted the Self-Portrait as a Soldier during his time recovering at a sanatorium in Halle. He has depicted himself in the uniform of the Königlich-Preußische Mansfelder Feldartilierie-Regiment Nr. 75 of Halle/Saale. It is a haunting portrayal. His face is drawn with a cigarette hanging loosely from between his lips. His eyes are unseeing and empty, without pupils and in the irises we can see the reflection of the blue of his uniform. What are the most striking aspects of Kirchner’s self-portrait are the lost right hand and its bloody stump. This grotesque aspect of the painting is the way Kirchner viewed his losses or possible future losses caused by the war. He is concerned that he will lose his ability to paint. He believes that all his creativity, artistic vision, and inspiration will be destroyed. Behind the self portrait stands a nude woman. There would seem little to connect the military man and her except that Kirchner may have wanted to think back on his early artistic days and his period where nudity dominated his works.

The style of Kirchner’s self-portrait is similar to his famous Berlin street scenes which he painted between 1913 and 1915. In those, like this work, the style he used was of a primitive manner. Kirchner had introduced primitivism to Die Brücke group. Primitivism is a reference to the use by Western artists of forms of imagery derived from the art of the so-called primitive peoples especially those who had been colonized by Western countries.

Although Expressionism is not my favourite artistic style I have enjoyed researching the work and life of Ernst Kirchner and will soon return to look at some of his contemporaries.