My last three blogs looked at Italian Renaissance paintings but today, and in my next blog, I want to move in a completely different artistic direction and look at the life and work of a man who is widely acknowledged as the greatest artist of German Expressionism. His name is Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Before I look at the early life of Kirchner I suppose I should explain a little about the term Expressionism. Expressionism came about around 1905 and lasted until about 1920. It is a term given to a style of painting, music, or drama in which the artist or writer seeks to express the inner world of emotion rather than external reality. This term Expressionism is applied to art which seeks to cause an emotional response, not to actual pictorial content but to the exaggerated style adopted by the artist who is seeking to reflect his inner self. The term is generally applied to modern European art, where exaggerated forms and vivid colours were employed. In Germany, at the beginning of the twentieth century, there was disillusionment with the old fashioned academic styles of painting and this prompted a flood of experimentation and innovation. The artists were desperately searching for a new way to express themselves through the medium of painting and by doing so convey their personal experiences of their new modern world with all its advancing technology. Expressionism is an artistic style in which the artist attempts to depict not objective reality but rather the subjective emotions and responses that objects and events arouse in him or her. They accomplish their aim through distortion, exaggeration, primitivism, and fantasy and through the vivid, jarring, violent, or dynamic application of formal elements. The actual term Expressionism was first used in the preface of the catalogue for the 22nd Berlin Secession Exhibition of April 1911 to describe the work of Braque, Derain, Picasso, Vlaminck and Marquet.

Kirchner was born in Aschaffenburg in northwest Bavaria in 1880 and is now looked upon as one of the most important representatives of Expressionism. Kirchner was brought up in a middle–class family environment. His father was an industrial chemist. Kirchner showed an early interest in drawing and as an extra-curricular activity, during his school years his parents arranged for him to have drawing and watercolour lessons at home. His parents support for his love of art was not wholehearted as they saw no future in their son becoming an artist and so after taking his final school leaving exams they insisted he attended the Königliche Technische Hochschule to study architecture. Kirchner went along with his parents’ plans as he believed the course would also allow him to have further training in art, such as freehand and perspective drawing. He took his preliminary diploma in 1903 after which he spent the winter term studying in Munich.

Whilst at the Hochschule he became close friends with another student Fritz Bleyl and later they, along with two other architecture students, Karl-Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel, after successfully completing their architecture degree course in 1905, formed an artist group which they called Die Brücke (The Bridge). The name, given to their group by Rottluff, was to symbolise a connection between Germany’s artistic past and future and they intended that their art would be that very link and the way forward. Theirs was a radical group which was opposed to middle-class conventions, which they considered lacked fervour, and it was their aim to shun the traditional academic style of art and initiate a new style of painting which would be more in keeping with modern life. They still saw their artistic work as belonging firmly within the tradition of German art, especially the art of Albrecht Dürer, Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach the Elder. This young group of artists was anti-establishment, liberal in their attitude and full of revolutionary ideas. Like all new groupings the four founders decided that the group should have its own manifesto setting out its ambitions. Kirchner was in the forefront of thinking up the wording for the manifesto and he clearly summed up what the group wanted to achieve:

“….. freedom in our work and in our lives, independence from older, established forces…”

The group met regularly at the Dresden studio of Kirchner. The lifestyle of this group was Bohemian in character. In the Royal Academy 2003 exhibition catalogue Kirchner – Expressionism and the city, a quote from Fritz Bleyl described his friend’s first studio, which had formerly been a butcher’s shop:

“…[it was] that of a real bohemian, full of paintings lying all over the place, drawings, books and artist’s materials — much more like an artist’s romantic lodgings than the home of a well-organised architecture student…”

In Kirchner’s studio social standards were largely ignored. Art historians quote reports of the goings-on which took place at the studio and recount tales of “much impulsive love-making and naked cavorting”. During these meetings at Kirchner’s studio, the artists met to study the nude in group life-drawing sessions. However, Kirchner wanted to distance himself from the rigid and painstaking academic style of life drawing and he and his fellow artists would instead sketch the naked women, quickly in quarter-hour sessions (Viertelstundenakte) and by so doing, they believed that they were able to capture the fundamental nature of their subject as instinctively as they could. The models who posed nude for Kirchner’s group were not professional models; they were just part of Kirchner’s circle of friends, who were only too willing to become part of this newly-founded art movement.

The lifestyle of the group in some ways was mirrored in the flower-power days of the 1960’s or the punk rock days of the late 70’s. They hoped and succeeded in shocking the bourgeoisie. Normal social conventions were abandoned and the group’s studio became a place almost of decadence with group life-drawing sessions, frequent nudity and casual love-making. Like Matisse and Picasso, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was fixated with the female nude, as a symbol of his own intense sexuality as well as it being a seductive return to primitive nature. The intention of Die Brücke artists was to wage battle against the constricting forces of bourgeois culture. To them this culture was linked indelibly with mediocrity, corruption, and weakness. Kirchner believed fervently on self-empowerment and complete freedom from convention and this could be seen in his early art which often concentrated on erotic subject matter. In the paintings done by Kirchner and the other artists of this group they often depicted the female nude crudely as both “primitive” and submissive. For them this depiction of the female signified both male domination and male virility.

In the September and October of 1906, a year after the formation of Die Brücke, the first group exhibition was held at the K.F.M. Seifert and Co. in Dresden. The works exhibited focused on the female nude and Fritz Bleyl designed the lithographic poster for the event. In 1906, Kirchner met Doris Große, who became his favoured model and remained at his side until 1911 when he decided to leave Dresden and move to Berlin. Doris would not make that journey. From 1907 to 1911, Kirchner liked to spend part of his summers at the Moritzburg lakes which lie to the north of Dresden. He and the other members of Die Brücke art group, along with their friends relaxed amidst the countryside tranquillity and led a relaxed communal lifestyle and embraced the popular German culture of going back to nature and dispensing with such frivolous things as clothes !

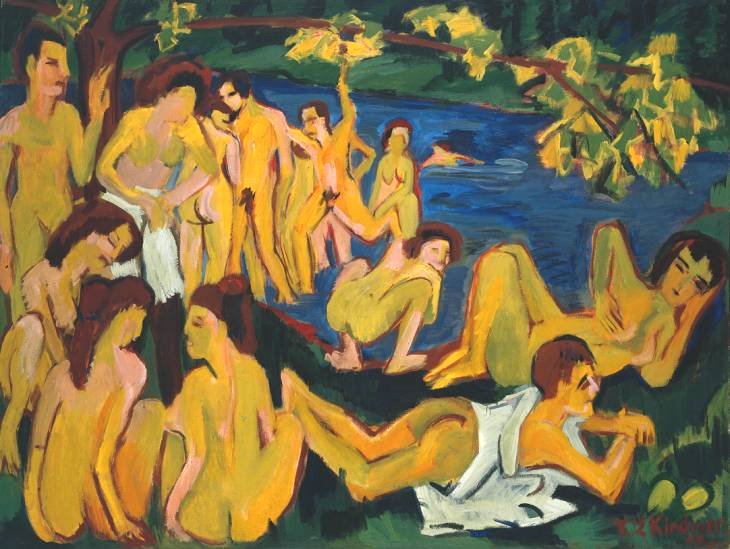

My featured painting today is by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and is entitled Bathers at Moritzburg which he completed around 1910. It is a painting depicting people who have for a short time shunned the claustrophobic and overpowering life in the city and have gone back to the freedom of nature. This is their reunion with nature. It is a painting full of energy. There is vigorous activity all around. The first thing that strikes one about this work of art is the overstated colours he has used in this painting. We have the contrast of the yellow-orange flesh of the bathers with the blue of the water. This contrasts serves to emphasise the nudity of the figures. Although I have dated the painting as being completed around 1909, the original effect may have been too extreme for Kirchner as in 1926 he repainted parts of the picture making the colours lighter and the surface of the painting more even. It is presently housed in the Tate Modern in London.

As a leading proponent of Expressionism how did Kirchner view his style? In a letter written in 1937 to art dealer Curt Valentin, he explained the development behind his own Expressionist style:

“…First of all I needed to invent a technique of grasping everything while it was in motion…I practised seizing things quickly in bold strokes, wherever I was and in this way I learned how to depict movement itself, and I found new forms in the ecstasy and haste of this work, which, without being naturalistic, yet represented everything I saw and wanted to represent in a larger and clearer way. And to this form was added pure colour, as pure as the sun generates it…”

In my next blog, I continue looking at the life of Ernst Kirchner as he moves to Berlin, suffers mentally from the rigours of World War I, splits from Die Brücke and spends the last years