Marriage and women destined to suffer.

In 1883 John William Waterhouse married Esther Maria Kenworthy, a noted flower painter. She was the daughter of James Lee Kenworthy, an artist and schoolmaster from Ealing and Elizabeth Kenworthy who was also a schoolteacher. Waterhouse was thirty-four-years-old and Esther was eight years younger. The marriage took place at the Church of England parish church in Ealing, and thereafter Waterhouse’s wife used the name Esther Kenworthy Waterhouse. At the beginning of their married life the couple lived close by a purpose-built artistic colony in Primrose Hill, where the houses also had studios. Primrose Hill Studios, built in 1877, was a development of twelve artist houses around a quadrangle in a mews off Regent’s Park. Waterhouse already rented a studio at No. 3 Primrose Hill Studios, which he had leased since 1878, and later moved to a much bigger studio at No.6.

One of the Waterhouses’ neighbours at the Primrose Hill Studios was the prolific Antwerp-trained English landscape, portrait, and genre painter, William Logsdail. The Primrose Hill Studios complex was, as Logsdail later recalled, a place that the artists around the courtyard ‘formed a happy family, in and out of each other’s studios during the day, and in the evening swapping stories over the cards and whisky or dining at “the Bull and Bush” on Hampstead Heath’.

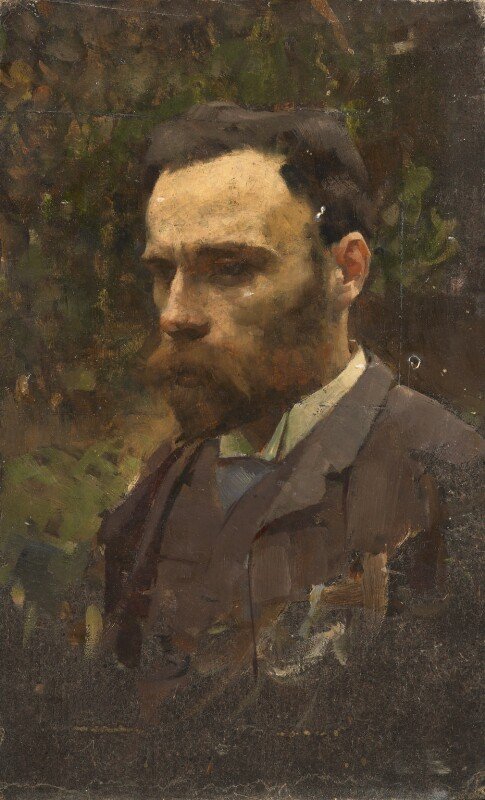

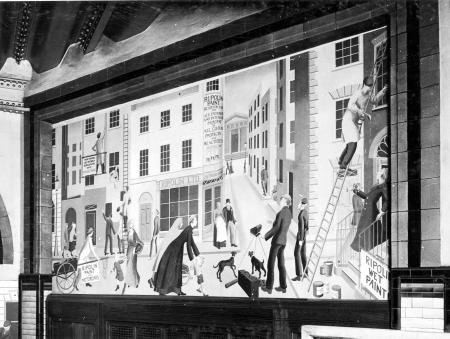

Logsdail recorded in 1917 that he used friends and colleagues from the Primrose Hill Studios – including four members of the Waterhouse family – to act as models for parts of his London cityscape paintings. It is the connection and friendship between Waterhouse and Logsdail, which brought about questions as to who painted the small oil on board portrait of Waterhouse in 1887. At first, it was looked upon as a self-portrait but in 2002 Peter Trippi, the leading authority on Waterhouse, questioned the attribution, suggesting that the sketch was not a self-portrait but in fact it had been painted by William Logsdail, In the painting we see that Waterhouse’s features half-hidden under a thick reddish-brown moustache and beard. The portrait went to auction, run by John Physick, Waterhouse’s great-nephew, at the Canterbury Auction Galleries, in May 2011. Even then, it was deemed as a self-portrait by Waterhouse. However, in Trippi’s words this head is ‘absolutely a modern-life image made by a trusted colleague or friend’. It is the first example of Logsdail’s work to enter London’s National Portrait Gallery Collection. The attribution to Logsdail has now been established beyond doubt.

In 1885 John William Waterhouse was elected as an Associate of the Royal Academy. This election to full membership status came shortly after he exhibited a painting, the depiction of which was one that engendered great discussion with regards its depiction. The work was entitled Saint Eulalia, who was a twelve-year-old martyr. When the work was exhibited it came with a note from Waterhouse:

“…’Prudentius says that the body of St. Eulalia was shrouded “by the miraculous fall of snow when lying in the forum after her martyrdom…”

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens was a Roman Christian poet who was born in Northern Spain and who practiced law, as well as holding two provincial governorships. He was awarded a high position by the Roman emperor Theodosius but tiring of court life, he devoted the rest of his time, from about 392, to writing poems on Christian themes.

Eulalia of Mérida was a devout Christian girl, aged between twelve and fourteen years old who lived in Mérida, Spain, and who was killed during the Persecution of Diocletian around 304AD. The Diocletianic persecutions, sometimes referred to as the Great Persecution, was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303 AD, the four Roman Emperors, Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius set out a series of pronouncements withdrawing the legal rights of Christians and ordered them to observe the traditional religious practices. The story goes that Eulalia ran away to the law court of the governor Dacian at Emerita, and stubbornly professed herself a Christian. She then went on to insult the pagan gods and emperor Maximian, and defied the authorities challenging them to martyr her.

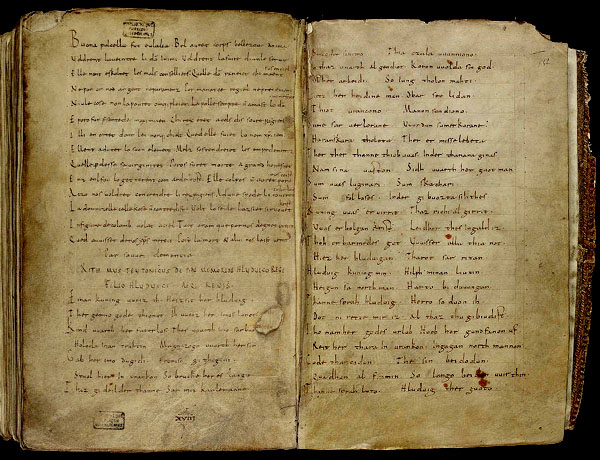

The story is told in a book of twenty-nine verses, The Sequence of Saint Eulalia, also known as the Canticle of Saint Eulalia, which is a ninth century biography of Saint Eulalia and tells how she resisted pagan threats despite being tortured. Finally, she was executed and became a Christian martyr. Below is a translation of a passage of The Sequence of Saint Eulalia.

Eulalia was a good girl,

She had a beautiful body, a soul more beautiful still.

The enemies of God wanted to overcome her,

they wanted to make her serve the devil.

She does not listen to the evil counsellors,

(who want her) to deny God, who lives up in heaven.

Not for gold, nor silver, nor jewels,

not for the king’s threats or entreaties,

nothing could ever persuade the girl

not to love continually the service of God.

And for this reason she was brought before Maximian,

who was king in those days over the pagans.

He exhorts her — but she does not care —

to abandon the name of Christian;

She gathers up her strength. And subsequently worship his god.

She would rather undergo persecution

Than lose her spiritual purity.

For these reasons she died in great honor.

They threw her into the fire so that she would burn quickly.

She had no sins, for this reason she did not burn.

The pagan king did not want to give in to this;

He ordered her head to be cut off with a sword.

The girl did not oppose that idea:

She wants to abandon earthly life, and she calls upon Christ.

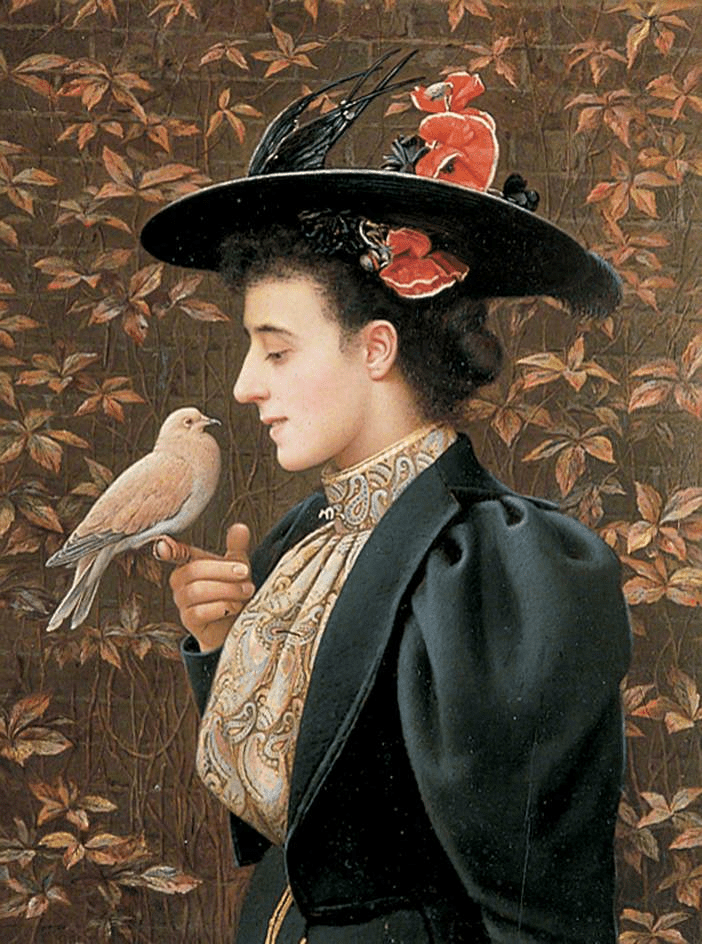

In the form of a dove she flew to heaven.

Let us all pray that she will deign to pray for us

That Christ may have mercy on us

And may allow us to come to Him after death

Through His grace.

For some, this painting by Waterhouse the pictorial story was a too gory and disturbing subject and for some it was too much to behold. Many of the public who had never heard of Eulalia were shocked by the story and depiction. For Waterhouse it was all about women being subjected to a horrible and undeserved fate, some of whom we will see in later paintings. Before us we see the foreshortened body of Eulalia which in itself often received criticism from critics of the time. As we look along the body from her head to her feet, our eyes are led to a void of snow which in a way underlines the young girls isolation. Her arms are outstretched forming a cross as if she has been taken down from a crucifixion and laid upon the floor which, of course, mirrors the fate of Christ. Hovering above her are white doves, one of which in the story of her martyrdom is said to have come from the dead girl’s mouth on its journey to heaven. This frightened away the soldiers from her body and allowed a miraculous snow to cover her nakedness, its whiteness indicating her sainthood. Look how Waterhouse has depicted Eulalia’s hair spread out like a fan. For Waterhouse, a woman’s hair was an object of male attraction. Although the painting shocked many who saw it at the 1885 Royal Academy Exhibition it secured Waterhouses election as a full member of the Academy. For all the painting recounts the martyrdom of a young virgin, Waterhouse was careful not to depict on her body the result of the savagery and butchery of her torture that preceded her death, instead he managed to secure the purity and innocence of her body.

Waterhouse’s fascination with doomed women can be seen in his 1887 painting entitled Mariamne. The story comes from an account in Josephus’ book Jewish Antiquities. Josephus was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian who was born in Jerusalem. In his book, Josephus recounts the story of Mariamne the Hasmonean, who he describes as a magnificently beautiful and dignified Hasmonean princess and the second wife of Herod the Great and sister-in-law of Salome. Herod feared the power of the Hasmoneans which led him to execute all the leading Hasmonean family members, including his wife, Mariamne, whom Herod had executed at the behest of sister Salome on a trumped-up charge of infidelity. The painting by Waterhouse was the largest he ever made, measuring 259 x 180cms. It is a wonderful painting full of fascinating narratives. Art critics of the time likened it to a scene from a play. The main figure of the work is the white-robed figure of Marianme who we see descending a marble staircase. Her hands are chained having been condemned to death by a group of elders seen lurking in the shadows in the background. Their decision being based on their loyalty to their king and not because they believed the charge of infidelity. To the right we see a man in crimson robes seated, listening intently to the whisperings of the women by his side. There is one line of thought that the interior painted by Waterhouse is reminiscent of the interior of his contemporary, Alma-Tadema’s Grove End Road, St John’s Wood studio/house. The painting was exhibited in Paris, Chicago and Brussels over the next ten years and by the beginning of the twentieth century Waterhouse had become world renowned.

Another of Waterhouse’s works featuring a doomed and maligned female is probably his best known. It is The Lady of Shalott which he completed in 1888. The Lady of Shalott is a character from Tennyson’s 1832 poem and recounts the story of a woman who is suffering under a curse of isolation. The woman’s home is a tower on a lonely island called Shalott. Running down past the island is a river which emanates from the castle of King Arthur’s and wends its way down to the town of Camelot. She had been incarcerated in her room, under a curse that barred her to go outside or even look directly out of the window in the tower. The curse forbids her to see the world other than that reflected images in her mirror.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

She would spend her time sitting below the mirror weaving a tapestry of scenes that she could only observe in the reflection of the mirror. One day she looks into the mirror and catches a glimpse of the reflected image of the handsome knight Lancelot.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell’d shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn’d like one burning flame together,

As he rode down to Camelot.

She is overwhelmed by his beauty and cannot resist looking at him directly. She is stricken by love and lust and turns to look out of her window. For her disobedient act the mirror cracks and she is cursed.

Out flew the web and floated wide—

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

“The curse is come upon me,” cried

The Lady of Shalott.

The lady leaves the tower and goes to the riverbank where she finds a boat. It is this point in the tale that is captured by Waterhouse’s painting. The lady is just about to slip the chain holding the boat to the shore. We see the lady in the boat, sitting on the tapestry she has just been weaving. There is a pensive air about her facial expression. She seems slightly fearful as she starts her journey. Her lips are parted as she sings, maybe to ward off her anxiety as she leaves the island and floats down the river towards Camelot.

And down the rivers dim expanse

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance —

With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

At the front of the boat is a lantern and a crucifix. Besides the crucifix we see three candles. Candles symbolise life, and in this painting, we see two have blown out and one is flickering in the strong breeze, signifying that the lady has little time left. This is not just the starting point of the journey. It is almost her last moments before she dies never having reached Camelot. Look at the sumptuous colours Waterhouse has used in the painting contrasting the stark white of her clothing. The painting was further enhanced by Waterhouse’s inclusion of naturalistic details such as the pied flycatcher which rests on the reed bed and the many water plants which were native to English rivers at the time.

Waterhouse completed two further paintings with the motif of The Lady of Shalott. The one he painted in 1894 is part of the Leeds Art Gallery collection. In this work Waterhouse captures the moment as the lady turns and rises from her chair, clutching her weaving shuttle, hesitating before the sight of Lancelot as the curse begins to take place and the mirror starts to crack. The tip of Lancelot’s lance points to the crack. Behind her we see the cracked mirror and the reflection of the knight. Look at her facial expression. It is a piercing gaze. It is a combination of anxiety and yearning, a yearning to free herself from captivity. It is an act of defiance on her part. It is her assertion that she should be free. For Tennyson the poem was an allegorical tale about the transition from innocence, repression to sexual revelation. Look how the golden thread used in her weaving has wrapped around her torso and how she is breaking free of its restraints as if she is a white moth emerging from its silk cocoon, which metaphorically is her sexual awakening following her catching sight of the famous knight. Behind her, in the right background of the work Waterhouse has once again depicted candles being extinguished by the wind signifying the coming of her death.

Waterhouse’s final version of the Lady of Shalott was painted in 1915 entitled I am Half Sick of Shadows, said the Lady of Shalott. This is the point in the poem before Lancelot appears as a reflection in her mirror. It is from this stanza that the painting gets its sub-title:

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror’s magic sights,

For often thro’ the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, came from Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead

Came two young lovers lately wed;

‘I am half sick of shadows,’ said

The Lady of Shalott.

Again, we see the lady in solitary confinement in her tower. She is stretching upwards with her hands behind her head in a rather sensual pose. She is thinking about love and contemplating her dash for freedom. In preliminary sketches for this painting, Waterhouse had portrayed the lady sitting exasperatingly slumped in the chair with her hand covering her face. In front of her is her loom and to her left we see her large mirror.

It is important to look carefully at the mirror to see how Waterhouse has carefully chosen what is reflected in it. It reflects the arches of the tower’s windows creating a “heart” shape which symbolises what the lady dreams of – love and to be loved. But, like the mirror itself, this will soon be shattered. The river is reflected in the mirror reminding us that this is the ladies escape route. Camelot is also reflected in the mirror. This is where Sir Lancelot rides to and from. The reflection at the bottom of the mirror is of the two young lovers. There is a look of frustration on the lady’s face, no longer satisfied by her weaving. Frustrated by her lack of freedom. The sight of the two lovers in the mirror is frustrating her. She realises she must escape captivity and does not fear the consequences.

It is important to look carefully at the mirror to see how Waterhouse has carefully chosen what is reflected in it. It reflects the arches of the tower’s windows creating a “heart” shape which symbolises what the lady dreams of – love and to be loved. But, like the mirror itself, this will soon be shattered. The river is reflected in the mirror reminding us that this is the ladies escape route. Camelot is also reflected in the mirror. This is where Sir Lancelot rides to and from. The reflection at the bottom of the mirror is of the two young lovers. There is a look of frustration on the lady’s face, no longer satisfied by her weaving. Frustrated by her lack of freedom. The sight of the two lovers in the mirror is frustrating her. She realises she must escape captivity and does not fear the consequences.

Waterhouse had been fascinated by Tennyson’s poem for almost thirty years and these three paintings are testament to him wanting to delve into the meaning of the work and express it pictorially.

..………………..to be continued.

One of her favourites was one she did of her three children.

One of her favourites was one she did of her three children.

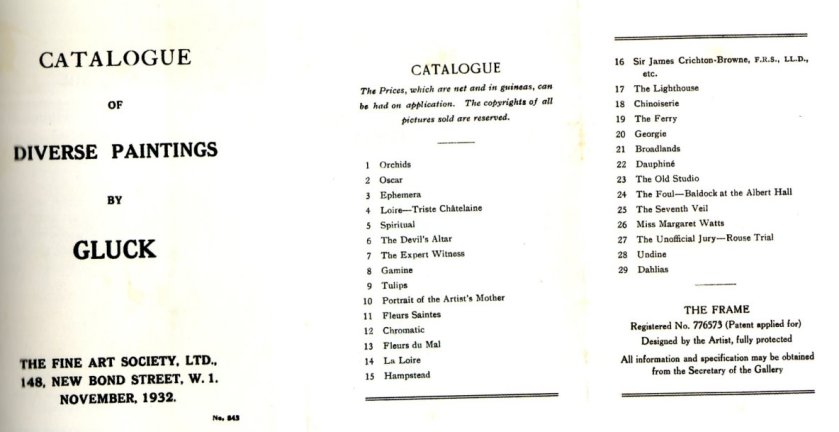

Most of the information for this blog came from two excellent books – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from two excellent books – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami. Gluck Art and Identity by Amy De La Haye (Author), Martin Pel (Author), Gill Clarke (Author), Jeffrey Horsley (Author), Andrew Macintos Patrick (Author)

Gluck Art and Identity by Amy De La Haye (Author), Martin Pel (Author), Gill Clarke (Author), Jeffrey Horsley (Author), Andrew Macintos Patrick (Author)

This close relationship with Nesta was to lead to Gluck’s most famous painting, completed in 1936, known as Medallion or the YouWe painting. The work is a portrait of Gluck and Nesta Obermer and according to Gluck it came about after the two women went to see the Mozart opera, Don Giovanni at Glynbourne on June 23rd 1936. Nesta and Gluck sat in the third row of the stalls and Gluck recalled how she felt the intensity of the music which fused them into one person and matched their love. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami describes the painting:

This close relationship with Nesta was to lead to Gluck’s most famous painting, completed in 1936, known as Medallion or the YouWe painting. The work is a portrait of Gluck and Nesta Obermer and according to Gluck it came about after the two women went to see the Mozart opera, Don Giovanni at Glynbourne on June 23rd 1936. Nesta and Gluck sat in the third row of the stalls and Gluck recalled how she felt the intensity of the music which fused them into one person and matched their love. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami describes the painting: