What is the reason behind you placing a paintings or prints on your walls at home? Is it because it reminds you of somewhere you have visited or maybe it is a depiction of somewhere nearby? Maybe it is a portrait of a loved one or somebody famous whom you admire. In this period of our lives when there is so much suffering going on around us then sometimes the painting is a depiction which simply lifts our spirits and makes us smile. Today I am looking at an artist and his work which fulfils that category. Let me introduce you to the English author, illustrator and humourist Graham Clarke. He has created over five hundred images of his beloved English rural life. He has focused on how the ordinary Englishman viewed Europe. Through his quirky depictions, he brings his own unique brand of humour to his interpretation of past and present history through the eyes of the common man.

Graham Clarke

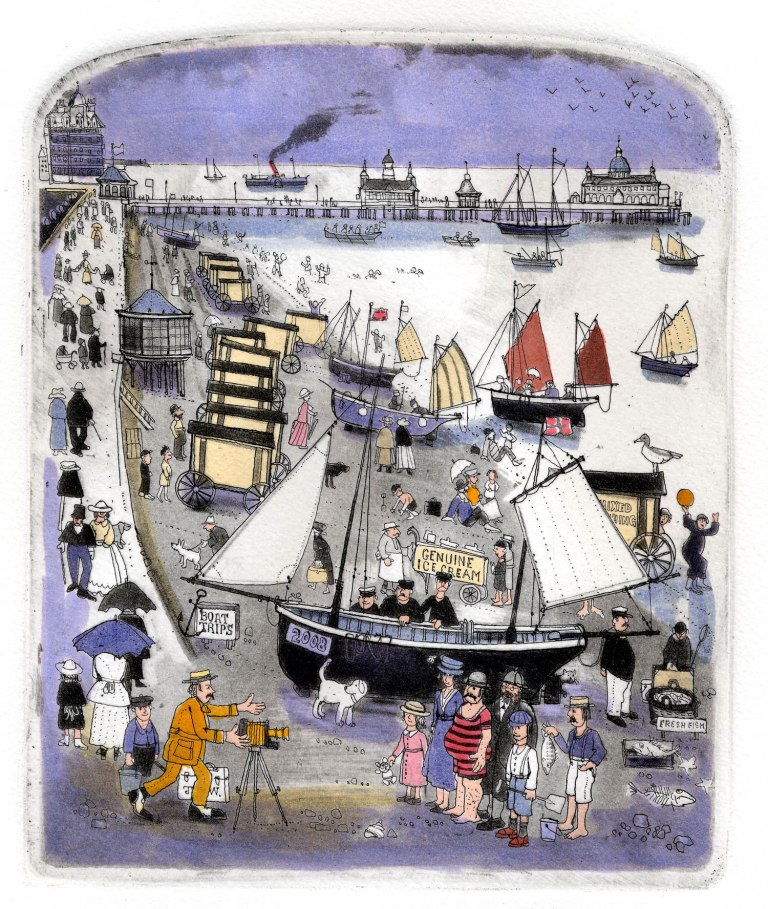

Graham Clarke was born on February 27th 1941 in a village in Oxfordshire during the Second World War. His father Maurice was a Midland Bank employee. He, his mother and his elder brother, Anthony, were evacuated there from their three-bedroomed semi-detached home in Hayes, Kent. When Graham was two years old the family spent a couple of months at the Cornish village of Denabole, which lies close to Trebarwith with its large expanse of sandy beaches which was always remembered fondly by Graham. In his teenage years Graham and the family would spend time at the coastal towns of Broadstairs and Looe and it was those holiday times on the coast that made a great impression on him.

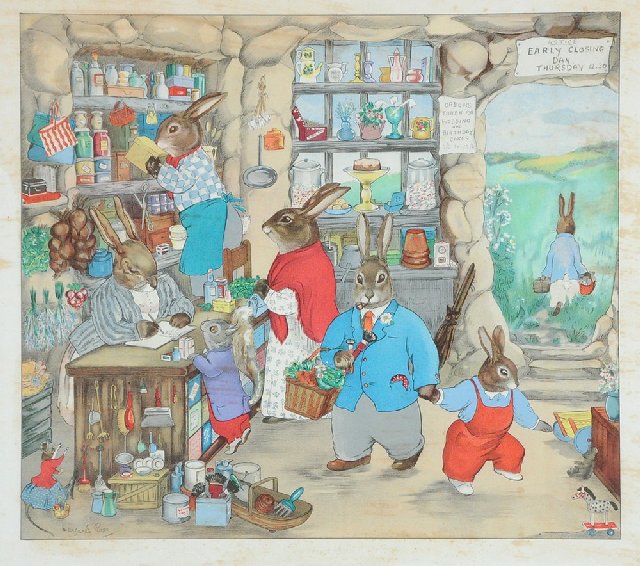

The Flippits. A Story of the Rabbit, Fox and Badger by Margaret Ross.

On his fourth birthday in 1945, with the war at an end, back living in Kent, Graham received a birthday present which was to remain in his memory in the years that followed. It was the children’s book, The Flippits. A Story of the Rabbit, Fox and Badger by Margaret Ross. It was a make-believe world, a world of peace unlike the threatening years that he and his family had experienced during the war. It was an underground world of a warren with its cottagey interiors. It was a book with illustrations which fuelled the imagination of four-year-old Graham. Looking at many of Graham’s multi-figured depictions one can look back at the multi-figured illustrations from this book and realise the connection.

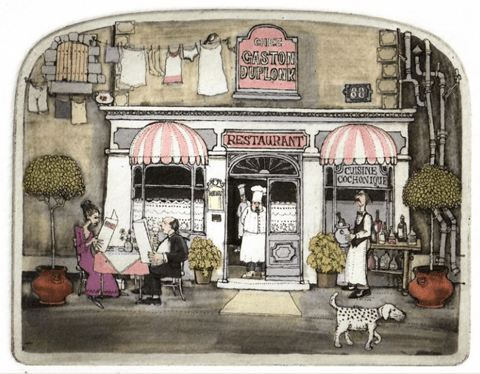

A la Carte by Graham Clarke

In 1949, when Graham was eight years old, the family left their home in Hayes and moved to a larger three-bedroomed semi-detached house. large enough to also accommodate Graham’s paternal grandfather who had been widowed. As a teenager, Graham was described as being an observant and sensitive child by his mother who would spend his free time cycling and exploring Hayes Common. He and his brother would also help their parents with their love of amateur dramatics and their AmDram group, The Hayes Players. Graham’s brother Anthony would help his parents by aiding with set building jobs and Graham would assist with painting stage portraits and stained glass windows.

Miss Jay’s Wood by Graham Clarke (1952)

One day Graham’s father came home and presented his son with a box of felt-tipped brushes and spirit-based inks and after the usual child-like sketches his artwork improved and he began to use watercolours for his countryside depictions. The box of watercolour paints with sable brushes and a set of oils had been a Christmas gift from his aunt and uncle in 1952 and on that Boxing Day he completed his first oil painting entitled Misses Jay’s Wood, which was owned by a close-by neighbour. The painting was bought by one of the neighbours for ten shillings. Graham could immediately envision himself as becoming a professional artist !

Meanwhile, Graham attended a small private school who fast-tracked their pupils’ education to be of a standard which would allow them to pass their 11+ exams. Whilst attending this school Graham let it be known of his future aspirations as a professional artist. However, he received no encouragement from his teachers, in fact, they told him it would be a pauper’s life for him if he were to realise his artistic dream. Notwithstanding this, he clung to his ideas and passed the 11+ exams and entered the Beckenham and Penge Grammar School in 1952. During his time there he enjoyed the geography and history lesson through his love of map-making and his fascination with castles and life for the working-class people of those times.

A book at the time which fascinated Graham was 1066 and All That, a tongue-in-cheek reworking of the history of England, written by W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman and illustrated by John Reynolds.

Another book which Graham loved was Down with Skool, by Ronald Searle which was one of his 1953 Christmas presents. He became interested in caricature. He excelled at art under Ronald Jewry, his art teacher who encouraged his students to use their imaginations when they painted. Graham Clarke enjoyed his time in the art class.

Graham received an excellent grade for his GCSE ‘O’ level Art and managed to scrape through Maths and Science sufficient enough to enter the sixth form ‘A’ level on a Science course but he hated it. His former art teacher, Jewry, approached his father and suggested that his son should abandon his A-level Science course and take up art instead. No doubt Graham had already spoken with his father over his future.

Graham’s favourite artist at this time was Samuel Palmer, born in 1805, a British landscape painter, etcher and printmaker who was also a prolific writer. Palmer was a key figure in Romanticism in Britain and produced visionary pastoral paintings. Graham believed that although he knew about the works of Palmer he realised that to get to really know him he had to visit the countryside around Shoreham, in west Kent, where Palmer had been so inspired. During his studies at the Art College Graham had enrolled in the History of Art Course and went on a short train journey to Shoreham. Graham was mesmerised by what he observed. He later wrote:

“…Palmer loved this place and love it is that makes me walk here too. Every lane is climbing up its hill [and] down again to the river, over the bridge and up and on again climbing and twisting. These are not mountains here there is no raging torrent, the trees are not giants and all is on a small scale, quiet and complete, Palmer decided God (and Nature) was at its best in this little valley of vision. Twenty miles from here is peace…”

Round and Round by Graham Clarke

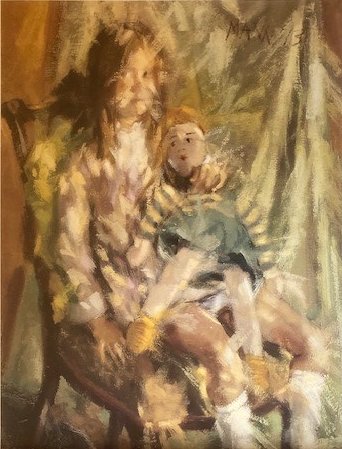

One of his tutors as the Beckenham Art School was Wolf Cohen who Graham described as “small, fiercely energetic and a model of dedication” and it was he who instilled in Graham that art should be life-absorbing. Although Graham’s figure drawing was not the best he managed to improve that during the time he spent in Susan Einzig’s life classes. She introduced Graham to the Laurie Lees’ book Cider with Rosie, illustrated by John Ward. It was these delicate and sensitive drawings that appealed to Graham.

Tea Party by Graham Clarke

At the start of his final year at the art college, Graham Clarke had to make a decision about his future. His tutor Wolf Cohen persuaded him to apply for a post-graduate position at The Royal College of Art and along with half a dozen of his fellow students he would spend weekends at Cohen’s studio building up his portfolio which would be needed when he applied to the college. Graham succeeded in his entry interviews and portfolio submission and in 1961 he became a student at the prestigious Royal College of Art.

Wendy by Graham Clarke. Pen and ink drawing from his sketchbook.

In his late teens Graham had been a member of various Youth Clubs, one of which was the Bromley High Street Methodist Youth Club and it was here that eighteen year old Graham first met fifteen year old Wendy Hudd and the two of them became involved with the organising of plays, pageants and parties.

The Four Seasons by Graham Clarke

Graham’s first year at the Royal College of Art was a disaster. He felt totally isolated from his fellow students and their interests in art. Whereas they looked for their inspiration by studying modern American magazine depictions of pop stars and flashy cars and motorcycles, Graham clung to his love of all things rural or historical and soon realised that he was going to be isolated by such loves. As he said, he was destined to “plough a lone furrow”. He decided to stay with what he loved and he was proud of this sincere decision and when challenged about it, would just say that he did not need to “ride another horse”. Graham described his first year as being a dark tunnel and yet he added he could just make out a light at the end of it. Graham was fortunate to have the support of Wendy and her family during those difficult twelve months.

Serenata by Graham Clarke

At the Royal College of Art Graham specialised in illustration and printmaking and had the chance to follow his interest in calligraphy.

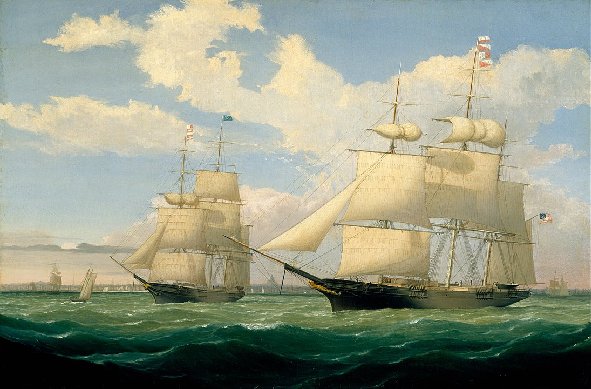

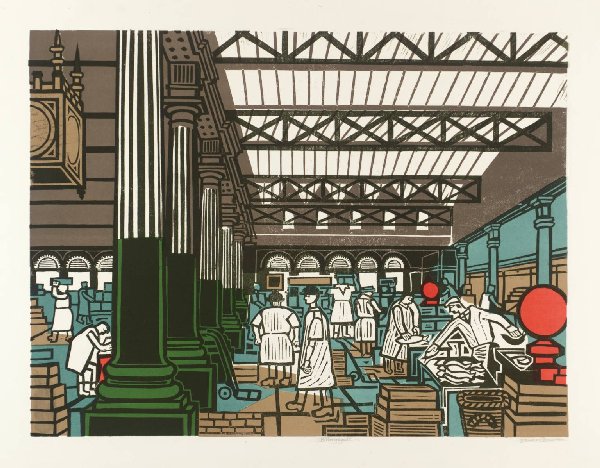

Billingsgate Market by Edward Bawden (1967)

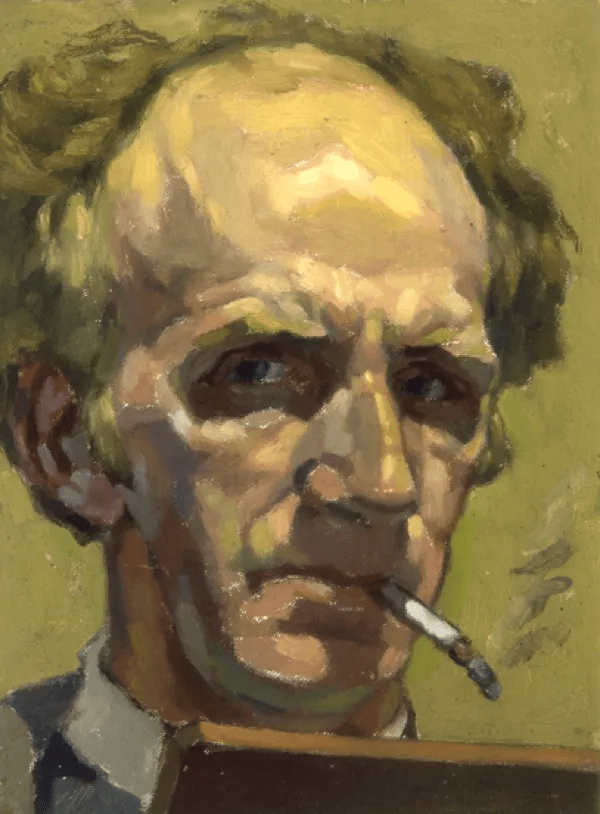

During his time at the Royal College of Art he was greatly influenced by one of his tutors, Edward Bawden, an English painter, illustrator and graphic artist, who was known for his prints, book covers, posters, and garden metalwork furniture.

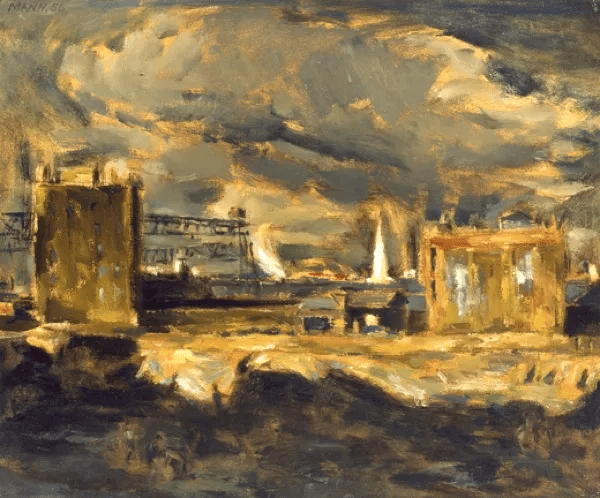

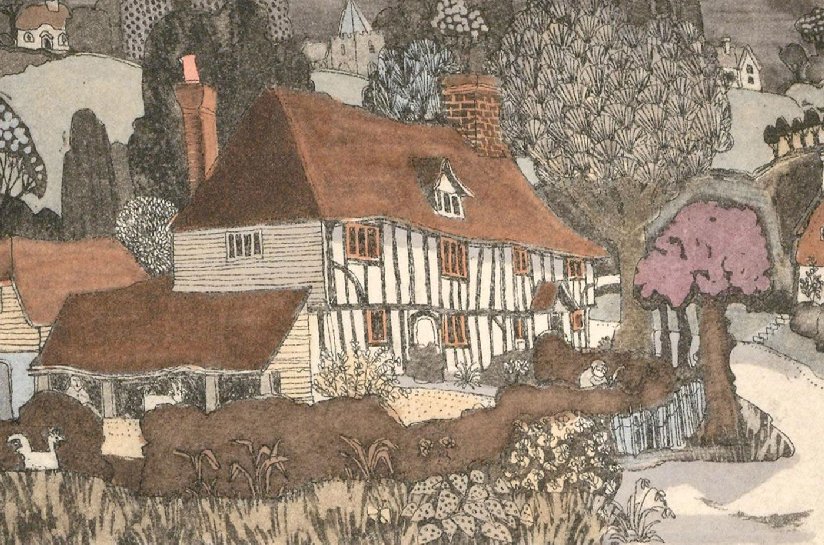

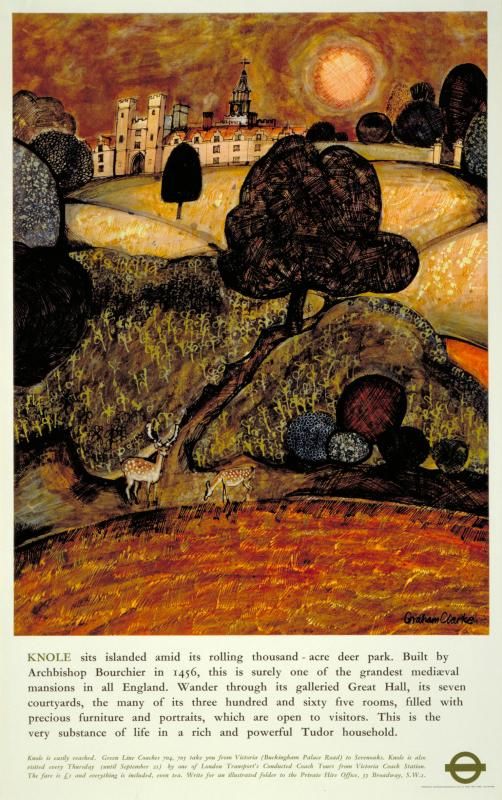

Yeomans by Graham Clarke

It was through Bawden’s influence that Graham took an interest in producing prints of traditional landscapes, the depictions of which highlighted local areas. One such print featuring a rural scene was Yeomans which depicted a quaint English street scene featuring cottages and trees.

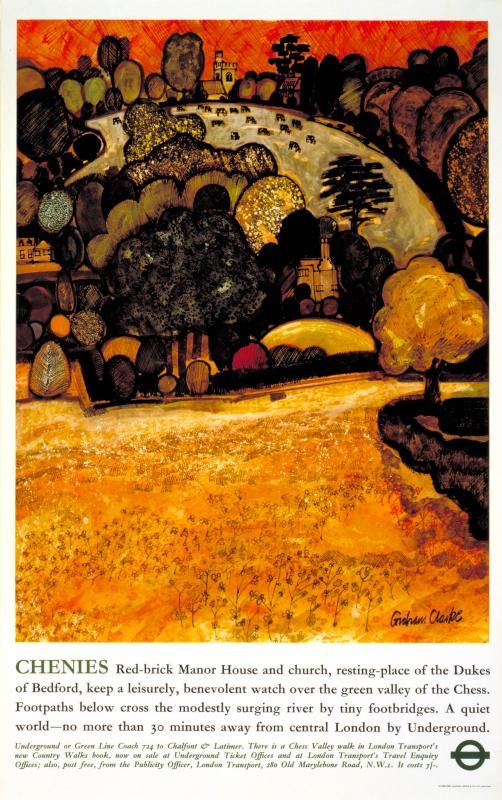

Graham finally graduated in 1964, which, fortunately for him, coincided with peoples’ interest in buying prints which resulted in a flourishing sale of them. His artwork was admired and he soon received commissions for his depictions from the likes of Editions Alecto and London Transport Publicity Department and so a bright career for him began.

Vision of Wat Tyler by Graham Clarke

In 1969 Graham’s first hand-printed “livre d’artiste”, Balyn and Balan was published. Another of his books was Vision of Wat Tyler which won recognition from the most influential patron and connoisseur of the day, Kenneth Clark. Lord Clark wrote enthusiastically in praise of Vision of Wat Tyler:

“…the whole book is a splendid assertion that craftsmen still exist and cannot be killed by materialism. A few idealists are the only hope for decent values…”

Dance by the Light of the Moon by Graham Clarke

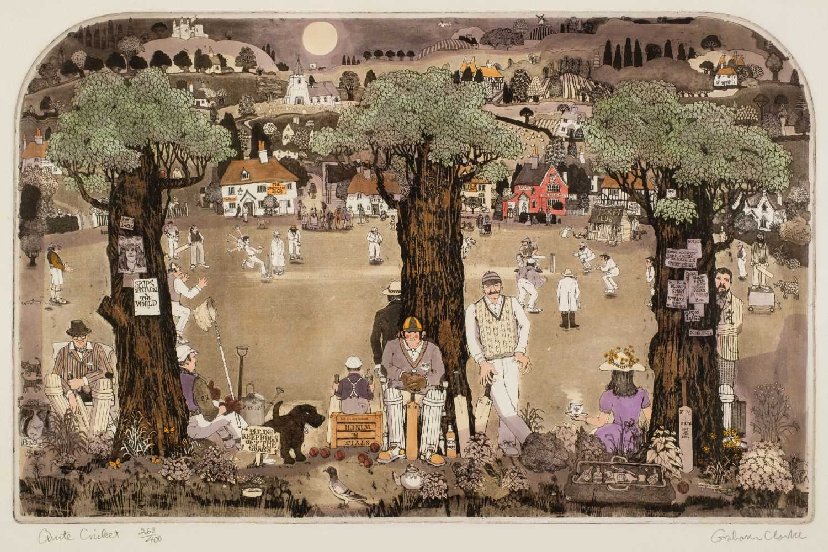

Graham’s famous ‘arched top’ etchings has established his widely successful reputation in Britain and overseas, and came to public attention in 1973 when the first of these, Dance by the Light of the Moon, was exhibited and sold in London at the Royal Academy of Arts Summer Show.

For you Madam by Graham Clarke

Examples of his work are held by Royal and public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the Tate Gallery and the National Library of Scotland in the United Kingdom, as well as by Trinity College, Dublin, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the New York Public Library and the Hiroshima Peace Museum. Many more are to be found on the walls of private homes all over the world, collected systematically by devotees, as well as singly by ordinary art lovers who “know what they like”

Quite Cricket by Graham Clarke

Graham Clarke, who prides himself as being a “Man of Kent” lives with his wife Wendy, four children, his animals and friends, in the village of Boughton Monchelsea in the county of Kent where he also has his studio.

He offers open-days at his studio which gives visitors an opportunity to view his work including hand coloured limited edition etchings, watercolours, posters and greetings cards depicting English rural life and history, the Bible and the Englishman’s view of Europe, all of which are available for sale.

My blog has only scratched the surface of the life of this talented artist. The information for this blog came from two main sources:

Clare Sydneys’ 1985 book entitled Graham Clarke

and