Somebody just asked me how I came to write about a certain artist. In the case of today’s blog it was just a strange coincidence………

In November 2012 I wrote a blog about the Barber Institute, an English art museum on the Birmingham University campus. The reason for visiting this gallery was to take in the exhibition of the Norwegian painter, with the English-sounding name, Thomas Fearnley.

Church at Ramsau by Thomas Fearnley (1832)

As I walked into the exhibition that day, the first painting I saw was a plein air oil on paper, laid on canvas work which Fearnley completed in 1832 while on his trek from Germany to Italy. Fearnley painted this finished composition from nature in September 1832. The artist was travelling to Italy when he stopped at the village of Ramsau. The title of the work was simply Ramsau. This was a town I knew well from the days I travelled around southern Bavaria. It was a beautiful painting, and I vividly remember the beautiful depiction as if I had just seen it today. It is a truly magnificent landscape work.

Wilhelm Bendz by Christen Kobke (c.1830)

The reason I mention this work is because the artist I am looking at today, Wilhelm Ferdinand Bendz, also produced an artwork featuring that same church with its mountainous background. Bendz was principally a painter of figure subjects and his landscapes are rare. This view was painted in September 1832 when he too was making his way from Munich to Rome. He stopped briefly at Ramsau in Austria and made several lively sketches of the church and mountains. His painting was dated the same month and same year as Fernley’s painting ! More about that coincidence later.

Winter Landscape from Funnen by Wilhelm Bendz (1831)

Wilhelm Ferdinand Bendz was born in the Danish town of Odense on the island of Funen on March 20th 1804 His father was Lauritz Martin Bendz, at one time, chief of police in Odense and High Court Judge in Funen and Langeland. His mother, his father’s second wife, was Regine Christence Bang. Wilhelm had four brothers and four sisters as well as three stepsisters and one stepbrother from his father’s first marriage.

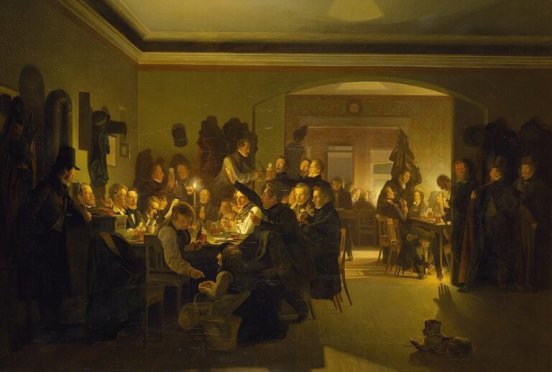

A Smoking Party by Wilhelm Bendz

Wilhelm Bendz, at the age of sixteen, having completed his schooling in Odense, travelled to Copenhagen where he enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and studied there from 1820 to 1825. Here he studied under Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, whowent on to lay the foundation for the period of art known as the Golden Age of Danish Painting, and is referred to as the “Father of Danish painting”. In his final year at the academy, he submitted work in an attempt to win the Academy’s prestigious gold medal prize which came with a travel scholarship. However, at the time, the Academy only awarded the Gold Medal to history paintings, which at the time was considered to be the most respected painting genre. Bendz, however, decided to concentrate on portraiture and genre works and his early paintings would often portray his artist colleagues and their daily lives.

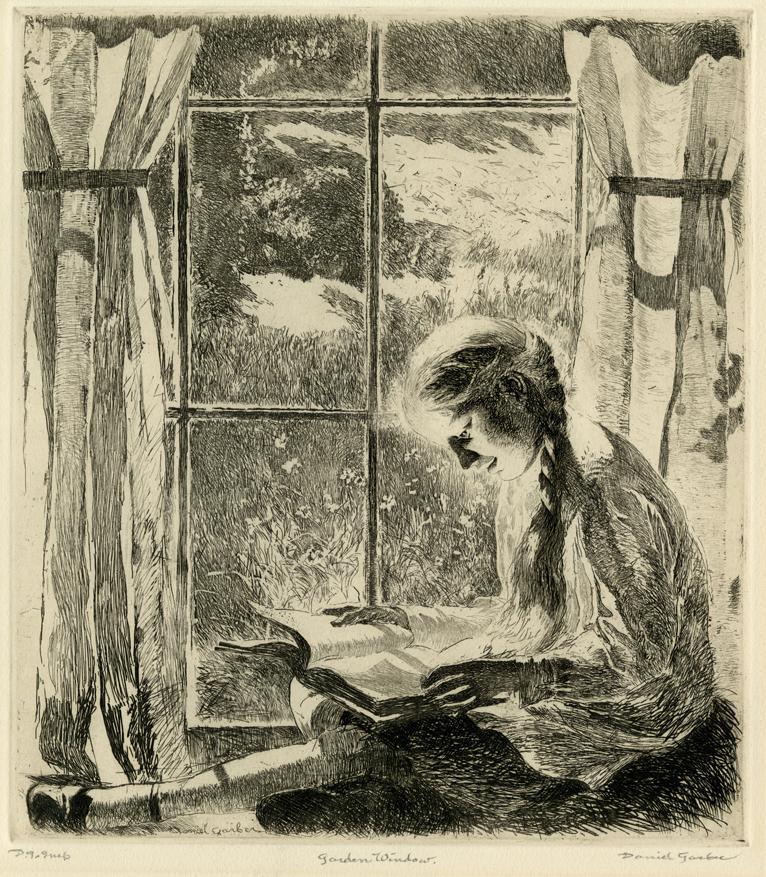

A Young Artist (Ditlev Blunck) Examining a Sketch in a Mirror by Wilhelm Bendz

One such work was his 1826 painting entitled A Young Artist (Ditlev Blunck) Examining a Sketch in a Mirror. Wilhelm Bendz was a great believer in artists’ new role in life. He believed they were no longer simply specialist craftsmen but, for him, artists should be viewed as intellectual workers. The artist in this picture is Bendz’s fellow Academy student, Ditlev Blunck, who is engaged in painting a portrait of fellow student, Jørgen Sonne, a painter who would become known for his battle scenes. The painting which Bendz completed in 1826 depicts young Ditlev Blunck, a fellow Academy student of Bendz, taking a break from painting to examine a sketch he has made for the portrait. The artist is standing in a crowded room surrounded by his tools and paraphernalia: a paintbox, palette, and easel as well as a skull and a sketchbook suggesting that careful studies had preceded the final painting. Only the back of the painting can be seen with the front seen only in the mirror. It is believed that the depiction is indicative of the era’s view of art as a mirror held up to life and signals that his work is serious, and requires thorough study before execution.

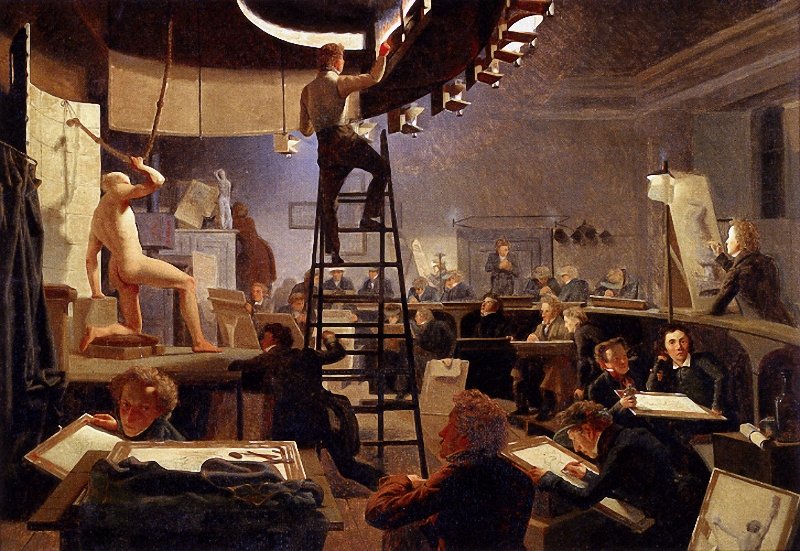

Model Class at the Copenhagen Academy by Wilhelm Bendz (1826)

Bendz completed Model Class at the Copenhagen Academy in 1826 and it is considered to be one of his greatest works.

Christian Holm by William Bendz (1826)

Another of Bendz’s works which focused on artists at work was one he completed in 1826 – a portrait of his fellow Academy student, Christian Holm, at work on his painting. Christian Holm became a well-known Danish painter known primarily for his animal and hunting scenes.

A Sculptor in his Studio Working from Life by Wilhelm Bendz (1827)

A Sculptor in His Studio which he completed in 1827 is one of Bendz’s masterpieces. It depicts the working environment of a sculptor with meticulous attention to tools, materials, and the creative process. The painting demonstrates his skill with complex interior lighting. The depiction is of sculptor, Christen Christensen, at work. Christensen was a Danish sculptor and medallist, who studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and was at the same time articled to the sculptor Nicolai Dajon. He won the Academy’s small and large silver medals in 1824, the small gold medal in 1825 and finally the large gold medal in 1827.

Interior from Amaliegade, Captain Carl Ludvig Bendz Standing and Dr. Jacob Christian Bendz Seated by Wilhelm Bendz (ca. 1829)

Bendz’s two brothers featured in an internal scene, in Bendz’s genre work entitled Interior from Amaliegade.

The Raffenberg Family by Wilhelm Bendz (1830)

The Waagepetersen Family by Wilhelm Bendz

Bendz often received lucrative commissions for family portraits.

Artist in the Evening at Finck’s Coffee House in Munich by Wilhelm Bendz (1832)

After leaving the Academy, Bendz was employed as an assistant at Christoffer Eckersberg’s studio. In late 1830 Bendz won an award which granted him a travel scholarship allowing him to leave Denmark and travel to southern Europe. After short stop-overs at Dresden and Berlin, he settled for a year in Munich, a city which had developed into a vibrant centre for the arts. This opportunity exposed Wilhelm to new artistic influences and techniques as well as knowledge of contemporary German painting, known as the Munich School, which seems to have influenced his style. It was here that he completed one of his most valued paintings, a composed group portrait entitled Artist in the Evening at Finck’s Coffee House in Munich.

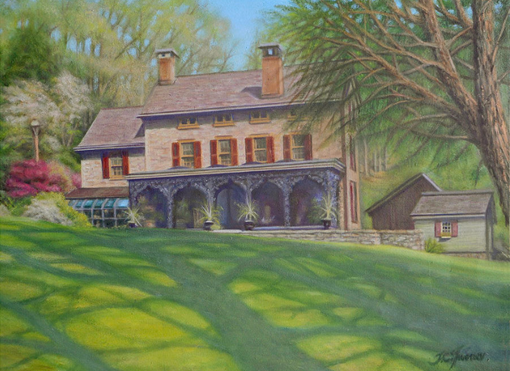

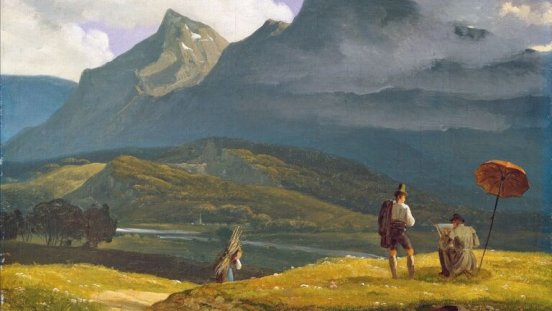

The Church at Ramsau by Wilhelm Bendz (1832)

In the autumn of 1832, twenty-eight-year-old Bendz left Munich and continued his exhausting journey over the Alps towards Rome. On this journey he was accompanied by Joseph Petzl, a German genre painter and Thomas Fearnley, a Norwegian romantic painter. It is here that I return to the start of the blog and the two similar depictions by Fearnley and Bendz of the church at Ramsau. The answer as to how Bendz and Fearnley completed paintings depicting similar views of the church in the mountains at the same time is now clear. They were fellow travellers and both had decided to record the beautiful scene.

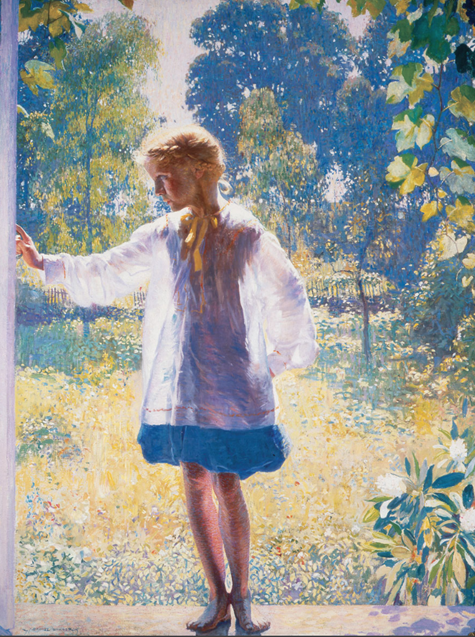

Mountain Landscape by Wilhelm Bendz (1831)

The three men finally crossed the Alps and made their way to Venice. The extremely difficult journey took its toll on Bendz and after moving from Venice to Vicenza to stay with a friend before heading to Rome, he collapsed and died of a lung infection on November 14th 1832 aged 28. Wilhelm Bendz’s artistic contribution was not appreciated during his short lifetime but his legacy grew significantly in the decades following, as art historians recognized his technical skill and unique perspective on the Danish Golden Age. Bendz’s technical skill was in the way he handled light, especially in interior scenes and how he enhanced the artistic achievements of the Danish Golden Age. His works displayed both academic precision and personal expression. He was a master at depicting the social life of artists and intellectuals, and this artwork provided valuable visual documentation of cultural circles in Copenhagen during the 1820s and early 1830s.