In my second part of my look at the life and works of Balthus I am going concentrate on his depiction of pubescent girls which were to shock both the public and critics alike when they first exhibited in 1934 at the Galerie Pierre in Paris. I have in some earlier blogs discussed what is, to some, termed as beautiful erotic art whilst others look upon the depictions as unacceptable and pornographic. Those paintings by the likes of Egon Schiele and Lucien Freud were depictions of adult female models but in the case of Balthus’ paintings the models he was using were pre-pubescent girls. I leave it to each person to decide whether the depiction of these young girls was simply the work of an artist and therefore as art, was acceptable or whether there was something very offensive and disturbing about the paintings. Everybody is entitled to their own opinion.

I need to remind you that the depiction of young girls naked or semi-naked in paintings is not just something that interested Balthus. Many other well known artists used young girls as models and portrayed them in their works of art.

There was Otto Dix, the German painter, and often talked about as the most important painter of the Neue Sachlichkeit, which was an artistic style in Germany in the 1920 which set out to confront Expressionism. It was looked on as being a return to unsentimental reality and one which concentrated on the objective world, unlike Expressionism which was more abstract, romantic, and idealistic. His 1922 painting Little Girl in front of Curtain, which can now be seen at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, was judged to have flown in the face of morality. This painting of a young naked girl is portrayed in a realistic style, maybe too realistic as it details the blue veins of her body. She looks emaciated and she stares past us with a haunted expression. Her childhood is probably a thing of the past as, sadly, is her innocence. A pink flower clings to the curtain behind her, and in her hair we see a bright red bow. The artist himself once said:

“…I will either become notorious or famous…”

This painting probably allowed Otto Dix to achieve his first goal.

The great Norwegian painter, Edvard Munch, who is best known for his paintings entitled Scream, also produced a painting in 1894 featuring a pre-teen naked girl. The painting which was entitled Puberty depicts a young pubescent girl, nude, sitting with her legs together. There is an air of shyness about her and this could be that at her age she is starting to become aware of the changes to her body.

The celebrated Austrian Expressionist artist Egon Schiele who, at the time, was living with his lover, Valerie Neuzil, in the small country town of Neulengbach, close to Vienna. This was a quiet suburban setting full of retired officers and snooping neighbours. Schiele was arrested in April 1912 on suspicion of showing erotic drawings to young children who posed for him, of touching the children while he drew them and of kidnapping one of the young girls who frequented his studio. Some of the charges were dropped and he spent three days in jail. A year earlier he produced the work entitled Standing Nude Young Girl 2.

The reason that I featured these three paintings was not that I considered them any sort of justification for Bathus’ portrayal of young girls but simply to point out that many artists have painted scantily-clad or naked young girls.

Balthus had been earning money with his portraiture, mainly of older society women, and he was very discontented with this. He actually hated this type of work calling his finished portraits, “his monsters”. In October 1935 Balthus moves to a new and larger studio at 3 cour de Rohan. Just three blocks away was the rue de Seine and it was at No. 34 that the Blanchard family lived, mother, father who worked as a waiter in a nearby bistro, daughter Thérèse and son Hubert who was two years older than his sister. When Balthus first caught sight of Thérèse she was just eleven years of age and having approached the family Thérèse agreed to model for him. She was not a beautiful girl but she appealed to Balthus.

The first painting Balthus completed of Thérèse Blanchard was in 1936 and was simply entitled Thérèse. Balthus would go on to use her as a model more than any other person. In this work, Balthus has captured her moody and serious look and it was that aspect of her that attracted Balthus to his young model. Her dark dress seems to go hand in hand with her mood and it is just the bright red piping on the collar of the dress which manages to liven up the portrait

In that same year Balthus completed a painting of Thérèse and Hubert entitled Brother and Sister. Once again Balthus has portrayed Thérèse’s expression as moody and sullen in contrast to the smiling happy face of her brother. Thérèse’s arms are wrapped round the waist of her brother, not as a sign of sibling affection, but as she was trying to make him stand still for Balthus. Their clothes are very plain. Hubert seems to be wearing the attire of a schoolboy whilst his sister is wearing a simple plaid skirt and a red sweater with a green collar.

In 1937 the two Blanchard siblings appear in a painting by Balthus entitled The Blanchard Children. Thérèse is now twelve years old and her brother is fourteen years of age. The setting is Balthus’ studio and one notices there are no childlike accoutrements such as toys, pens or books. It is a very stark depiction. This was not an oversight by Balthus but his belief that the starkness would intensify the dramatic effect of the picture. If we look under the table, we can see a bag of coal sat in the corner. Why would Balthus add this? The answer maybe that Balthus, whilst living in Germany, remembered what happened on the eve of the Feast of St Nicholas on December 5th when children put their shoes out in the hopes of some sweets in the morning. The story goes that, St. Nicholas does not travel on his own but with his companion, Black Peter, who places coal in the shoes of the children who had been naughty !

The strange posture of the two children is probably based on an illustration Balthus produced for Emily Bronte’s 1847 novel Wuthering Heights. The illustration relates to Heathcliffe, partly kneeling on the chair, turning towards Cathy who is on her hands and knees partly under the table, writing her diary. The painting was given to Balthus’ friend Picasso.

The first controversial painting Balthus did with Thérèse as his model was completed in 1937 and entitled Thérèse with Cat. It was a small work measuring 88 x 77cms (34 x 31 in). Here once again we see the un-smiling Thérèse seeming to look at something behind us. She looks slightly dishevelled with one sock down to her ankle and one sleeve pushed up her arm. The red and the turquoise colour of her clothes stand out against the dark background. Her left leg is raised and her foot rests on a stool and this pose means that her white underpants are visible to the viewer. She has been asked to pose in a certain way and by the look of her expression she is well aware of how the artist looks at her. A large cat lies on the floor next to Thérèse. It appears to be the same cat that appeared with Balthus in the painting King of the Cats (see previous blog). The painting is now housed in The Art Institute of Chicago.

One of his best known works is one he started just before the onset of World War II but was not completed until March 1946. It was entitled The Victim. It was one of his largest paintings measuring 132 x 218 cms (52 x 86in) and it was because of that size of it that he had to leave it in his Paris studio when he and his wife, Antoinette, at the onset of war, moved to Champrovent in Savoie which had not been occupied by the Germans. They later moved to Switzerland to live with Antoinette’s parents and did not return to his Paris studio until March 1946. We see a life-sized ashen body of a naked woman lying on a white sheet which covers a low bedstead. Is she merely asleep or is she dead? Does the title answer the question? The title comes from a novella written by Balthus’ friend, the writer Pierre Jean Jouve. His 1935 book La Scène capitale contained two novellas, La Victime and Dans les années profondes.

Below the bedstead and in the right foreground of the painting we can just make out a knife lying on the dark floor, the blade of which points directly to her heart. Although, through the painting’s title we gather that the girl is dead, there is no sign of a wound on her body and neither blood on her body nor on the knife. Was she strangled? So it is up to us to decide whether the girl is dead or simply in a trance but we must remember that Balthus started to paint this before war broke out and only concluded it a year after the end of the war and the atrocities of war would be fresh in the artist’s mind. Another question is, who sat for this painting and the answer is in some doubt. The shape of the girls face and the cut of her hair leads many to believe it is Thérèse Blanchard, the only doubt being that she had never before posed nude for Balthus

A year later (1938) Balthus completed Thérèse Dreaming, another but similar painting to to Thérèse and the Cat, again featuring the now thirteen year old Thérèse. The setting is once again his studio and we see her sitting before us in a similar pose. This is a much bigger painting, measuring 150 x 130cms (59 x 51 in). This time he added a striped wallpaper (which did not exist in his studio) as a background and this time we can see the additional still life of a vase and a canister on a table. The cat is once again part of the picture and we see it at the side of Thérèse lapping up some of its milk. In the previous painting Thérèse was looking almost towards us but in this painting but in this work she has looked away, with her eyes closed, as if enjoying a daydream. Thérèse’s clothes are unadorned and unfussy. As Sabine Rewald wrote in her book Balthus Cats and Girls :

“…she appears the epitome of dormant sexuality. Her white lace-trimmed slip surrounds her legs like a paper cornucopia wrapped around a bunch of flowers. The cat lapping milk from a saucer serves as another tongue in cheek erotic metaphor…”

Since 1998 the painting has been housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York as part of the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection.

By far the most controversial and notorious painting by Balthus was one he completed in 1934 entitled The Guitar Lesson. It is a merging of sex and violence which shocked those who saw it. It is an encounter between a dominating and tyrannical women, who is the music teacher, in her early twenties, and a young girl, her student, thought to be about twelve years old. The music lesson has been halted. A guitar lies on the floor and the woman has thrown the girl across her lap and pulled her black dress up over her waist. The fingers of the teacher’s left hand dig into the upper part of the girl’s inner thigh. It is as if the teacher is strumming a human guitar. The girl lies there, naked from her navel to her knees. The lower parts of her legs are covered by white socks. The music teacher has grabbed a chunk of the young girl’s long hair and is yanking her head downwards. To save herself from falling and in an attempt to alleviate the pain caused by her hair being pulled, the girl has grabbed the collar of the music teacher’s grey dress which uncovers the woman’s full right breast. Her nipple juts out which indicates to us that the teacher is sexually aroused by what she is doing.

The positioning of the girl lying across the thighs of the teacher has often been likened to the 1455 painting Balthus must have seen in the Louvre, Pietà of Villeneuve-les-Avignon by Enguerrand Quarton.

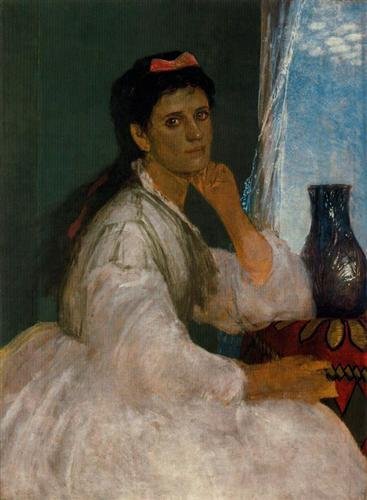

The girl who posed for The Guitar Lesson was Laurence Bataille, the daughter of a concierge. She would come to Balthus’ studio with her mother who acted as her chaperone. The striped wallpaper background and the grey dress of the music teacher were the same as we see in Baladine Klossowski 1902 portrait by her older brother Eugen Spiro. It was first shown at Balthus’ one man exhibition in April 1934 at the Galerie Pierre in Paris. The gallery owner, Pierre Loeb, and Balthus decided that the painting should be placed in the back room of the gallery, but covered up, so that it, in fact, became a “peep show” for a select “priveleged” number of visitors. The provenance of the painting is quite interesting. It was bought by James Thrall Soby, an American author, critic and patron of the arts, in 1938. He had intended to exhibit along with his other paintings at the Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut but because of the controversial nature of the painting it remained unseen in the museum vaults. Soby realised that there was no point in owning a painting that could never be exhibited and so, in 1945, he exchanged it with the Chilean surrealist artist, Roberto Matta Echaurren, for one of his paintings. Roberto Matta Echaurren’ wife Patricia left him and married Pierre Matisse but one of the things she took with her was this painting. Pierre Matisse, the youngest child of Henri Matisse owned a gallery in New York and the painting remained hidden away in the vaults. In 1977, it appeared for a month at Pierre Matisse’s 57th Street gallery in New York. It was a sensation and the press reviews referred to the painting and the art critics of the various newspapers and magazines wrote about it but said that they could not show the painting as it would shock the readers. After the one month long show it was never exhibited again.

When the 1977 exhibition closed the gallery offered it to New York’s Museum of Modern Art. It was accepted by the museum but it was not put on show instead it was kept hidden away for five years in the basement. In 1982 the Chairman of the Board of the MOMA, Blanchette Rockefeller, the wife of John D Rockefeller III, saw it at a small presentation of the works of art given to the MOMA by Pierre Matisse. She was horrified by Balthus’ depiction terming it sacrilegious and obscene and demanded that it was returned to the Pierre Matisse Gallery immediately. The Pierre Matisse gallery took it back and then sold it in 1984 to the film director, Mike Nichols. In the late 1980’s he sold it to the Thomas Ammann Gallery in Zurich. They sold it on to an unknown wealthy private collector who I saw in one newspaper report, was the late Stavros Niarchos. On his death in 1996 the painting became the property of his heirs.

In my next blog I will take a last look at the life of Balthus and share with you some more of his artworkwork.

—————————————————————————

Besides information about the life of Balthus and his art gleaned from the internet I have relied heavily on two books which I can highly recommend.

Firstly, there is an excellent book entitled Balthus Cats and Girls by the foremost expert on Balthus, Sabine Rewald.

Secondly, a very thick tome by Nicholas Fox Weber entitled Balthus, A Biography.