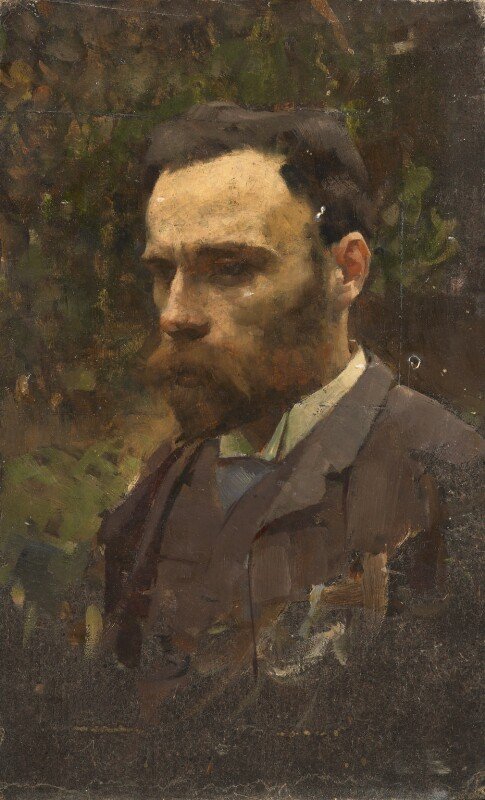

The portraiture of Ilya Repin

This is my first blog in a series which looks at Russian portraiture on display at the Tretyakov Gallery. As I wrote in my previous blog about the art gallery, the founder Pavel Tretyakov had wanted to have a large collection of portraits of famous Russians in his gallery. The first Russian artist I am featuring, who has paintings in Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, is Ilya Repin.

Ilya Yefimovich Repin was born in the southern Russian (now Chuhuiv, Eastern Ukraine) town of Chuguyev close to the Georgian border on July 24th, 1844. He was the fourth of six children of Efim Vasilievich Repin and his wife Tatyana Stepanovna Repina. His parents were a family of military settlers. Military Settlements in those days were places at which there was a combination of military service and agricultural employment. His father traded horses and his grandmother ran an inn. From the age of ten, Ilya studied at the Chuhuiv School of Military Topography and in 1857, Ilya studied art as an apprentice with the local icon painter, Ivan Bunakov. During his apprenticeship he would help paint icons and frescoes for the local churches. Throughout his life religious representations remained of great importance to him.

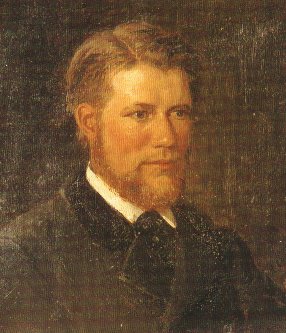

Even at the early age of fifteen, Repin demonstrated a rare talent for painting portraits which can be seen in his 1859 painting of his maternal aunt, Agrafena Stepanovna Bocharova, entitled Portrait of A.S. Bocharova, the Artist’s Aunt.

In 1863, at the age of nineteen, Repin moved to St Petersburg and enrolled for a one-year course at the School of Drawing of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists, a school which was created by a decree of Tsar Nicholas I in 1839 and was a preparatory school for the St. Petersburg Art Academy. Here he studied under the portrait painter Rudolf Zukowski and the Realist painter, Ivan Kramskoi, an intellectual leader of the Russian democratic art movement in 1860-1880.

It was whilst at that artistic establishment that the Rebellion of the Fourteen took place in September 1863. The rebellion consisted of fourteen young artists who left the Academy in protest against its rigid neoclassical dicta and who refused to use mythological subjects for their diploma works. The rebel artists insisted that art should be close to real life and they formed the Society of the Peredvizhniki to promote their own aesthetic ideals. In order to reach the widest audience possible, the society organized regular travelling exhibitions throughout the Russian Empire.

In 1864, Repin, having completed his preparatory year, was accepted at the Imperial Academy of Arts. Repin completed another portrait of a family member in 1867. It was a painting featuring his younger brother, Vasily Efimovich Repin.

Later, Repin would be become a close friend and associate with some of rebel artists of the Society of the Peredvizhniki and fifteen years on after returning from Europe he would join the group. But for the time Repin remained at the Academy and in 1871 won the prestigious Major Gold Medal award and received a scholarship to study abroad.

In 1872 Repin married Vera Alekseevna Shevtsova and in 1873 they travelled to Paris where Repin exhibited work at the Salon. The marriage lasted ten years but ended in divorce in 1884, on the grounds of Repin’s infidelity.

In 1874 whilst living in Paris Repin was contacted by Pavel Tretyakov who offered him a commission to paint a portrait of Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, a popular Russian novelist, short story writer, poet, and playwright who at the time was also living in the French capital. Turgenev was at the time the undisputed figurehead of the Russian artistic community in France. Repin was delighted and proud to be asked to paint the portrait of such a famous and influential man and Turgenev in turn held Repin in high regard as can be seen in a letter he wrote to the writer and art critic, Vladamir Stasov in November 1871, praising the talent of Repin:

“…I was delighted to learn that the young man [Repin] is moving ahead so vigorously and rapidly. He has great talent and unquestionably the temperament of a painter, which is most important of all…”

Pavel Tretyakov planned to fill his museum with portraits of the “great and the good” of Russia and a portrait of Turgenev was a prime example of what he wanted. Vasily Perov, another Russian portrait artist, had already completed a portrait of Turgenev in 1872 but Tretyakov was unimpressed by it and so had approached Repin, who by this time had established a reputation as one of the most promising artists of his generation. Tretyakov was pleased with the Repin’s final portrait but Turgenev was less pleased with the result. Turgenev was a steadfast supporter of modern French painting which he considered should serve as a model for Russian artists. Repin disagreed and poured scorn on the French paintings Turgenev was buying. The portrait of Turgenev prompted such heated debate, with one side who believed Russian artists should follow the Western style of painting whilst the opposing view was one which believed Russian artists and their art should follow their own path. The extent to which Russian artists should look inward or outward for inspiration was becoming a highly controversial debate.

Alexei Pisemsky was a novelist and dramatist, who, in the late 1850’s was looked upon as an equal to Turgenev and Dostoyevsky and in the late 1850’s wrote two hard-hitting books, One Thosand Serfs and A Bitter Fate both of which were critical of the peasant/master relationship. Later in the 1870’s he wrote about the evils of Russia’s emergent capitalism but his later books were often ignored by the reading public. Despite his fall from grace Pavel Tretyakov wanted Pisemsky’s portrait in his Moscow gallery and commissioned Repin to complete the task. Repin’s 1880 portrait of the fifty-nine-year-old Pisemsky depicts him as an ageing man with pouchy eyes clutching a walking stick. His coat is rumpled and his bow-tie droops giving the impression that Pisemsky’s best days are well passed and yet he seems alert and looks at us with a fixed stare. Alexei Pisemsky died shortly after the portrait had been completed.

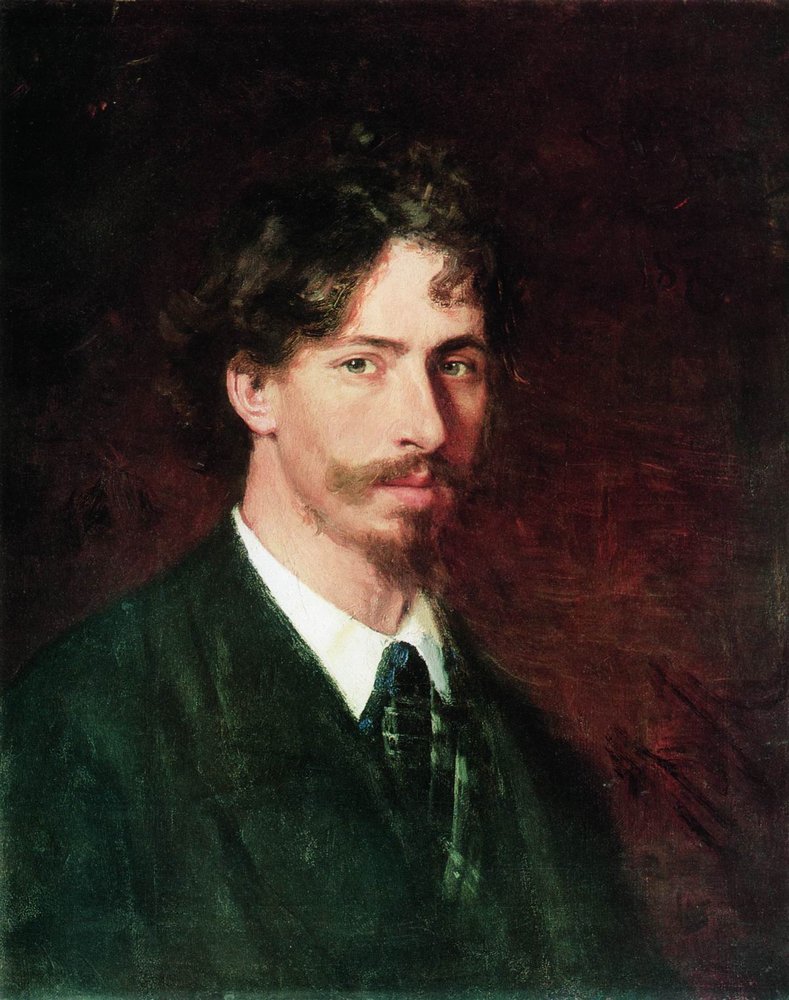

One of Repin’s most moving and beautiful portraits was of the Russian composer, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky. He was, as well as working as a civil servant, a giant of Russian music and was therefore an ideal subject for one of Pavel Tretyakov’s paintings. Although a genius, Mussorgsky had one great failing; he was an alcoholic. Mussorgsky’s decline in health became increasingly steep and he was increasingly unable to resist drinking. He was aware of the dangers of alcoholism and despite a succession of deaths among his closest associates which caused him great pain, he was unable to abstain. The decline could not be halted, and in 1880 he was finally dismissed from government service and through help from friends, managed to stave off destitution.

In early 1881 Mussorgsky suffered four seizures in rapid succession and was hospitalized. It was at this time that Tretyakov commissioned Repin to paint Mussorgsky’s portrait. Repin started the work on March 2nd 1881 in the ward of the Nikolaevsky Mlitary Hospital. It was the day after Emperor Alexander II was assassinated by, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, a young member of the Narodnaya Volya, a radical political organisation. Repin wrote about working on Mussorgsky’s portrait in the hospital ward:

“…When I painted M.P.’s [Mussorgsky’s] portrait in the Nikolaevsky Hospital, a terrible event had just occurred: the death of Alexander II; and during the breaks between sittings we read a mass of newspapers, all on one and the same terrible topic……[Mussorgsky] lived under a strict regime of sobriety and was in a particular fine sober mood….But as always, alcoholics are gnawed by the worm of Backus; and M.P. was already dreaming of rewarding himself for his long patience. Despite strict orders forbidding cognac…..an attendant obtained a full bottle of cognac for M.P.’s birthday…. My last session was planned for the next day. But when I arrived at the appointed hour, I did not find M.P. among the living…”

Mussorgsky died a week after his 42nd birthday. This beautiful portrait depicts the composer wearing a dressing gown. The striking burgundy decorative flap frames the florid features of this once-great man. We catch a glimpse of his highly decorative shirt between the folds of the dressing gown. His expression is one of rebelliousness but with a hint of feared inevitability. His eyes are turned away from us maybe in embarrassment at his parlous state. His hair and beard are unkempt. It is an uncompromising portrait but ever so poignant. Repin refused to keep the commission fee that Tretyakov gave him for the portrait and donated it to a memorial for the composer. Pavel Tretyakov was delighted with the finished work as he recognised it as one of the most passionate and emotional deathbed portraits of all time.

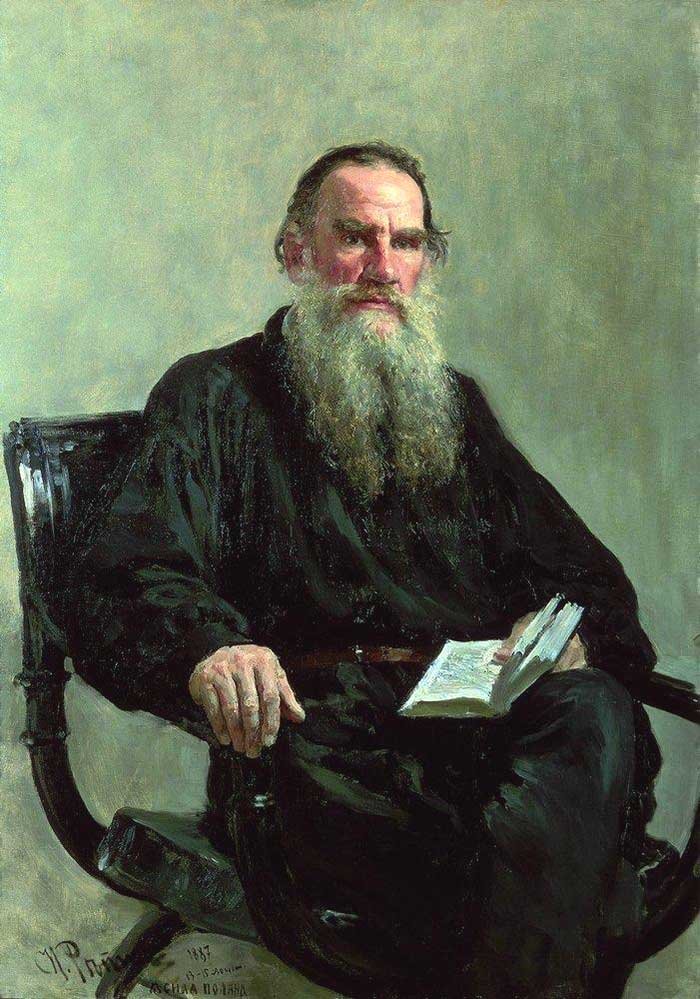

With Pavel Tretyakov’s desire to build a collection of portraits of famous Russians for his gallery, it was inevitable that he would want a painting depicting the great writer Leo Tolstoy who had cemented his position as one of the greatest writers of the century with his 1869 historical novel, War and Peace and his 1877 novel Anna Karenina. Through an introduction by Vladamir Stasov, the art critic, Repin and Tolstoy met in Moscow in 1880. Vladamir Stasov pointed out to Tolstoy that Repin’s exalted reputation in painting was the same as Tolstoy reputation in literature. By 1880, despite Tolstoy being a prominent writer he began to renounce his earlier works and decided to devote himself to religious and philosophical enquiry. He was in a state of “spiritual quest”, re-evaluating the values and his achievements of his earlier years. He took to wearing peasant clothes and renounced earthly pleasures. That first meeting of the two great men took place at Repin’s studio and Repin often visited Leo Tolstoy at his house in Khamovniki in Moscow. A number of portraits of Tolstoy were completed by various artists in the 1870’s but Ilya Repin’s worked on the great man’s portraits in August 1887 when he stayed with Tolstoy for eight days at his estate, Yasnaya Polyana at Tula, some 120 miles south of Moscow. In all, Repin produced twelve portraits, twenty-five drawings, eight sketches of Tolstoy and his family members, as well as seventeen illustrations to enhance Tolstoy’s works.

One of the portraits entitled The Ploughman. Leo Tolstoy ploughing, depicts the fifty-nine-year-old artist guiding a plough in bright sunlight. Repin remembered his time at Yasnaya Polyana and watching Tolstoy move around his estate, talking to the peasants. Repin recalled one hot day in August when Tolstoy was in the field ploughing for six hours without a break. Repin said that he had his sketchbook with him and kept sketching each time Tolstoy with his horse-driven plough passed by. Lithographic prints depicting Tolstoy the Ploughman followed and they were popular throughout the whole world.

In that same year, 1887, Repin completed a large portrait of Tolstoy sitting in a chair dressed in a black robe. On his knee is a book which Tolstoy has marked in two places as if to emphasise his passion for reading.

Another stunning portrait by Ilya Repin which hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery is entitled Portrait of Baroness Varvara Ikskul von Hildenbandt which he completed in 1889. It is a narrow oil on canvas work with unusual dimensions. It is 197cms tall and yet only 72cms wide and yet it skilfully depicts this beautiful slender woman. Baroness Varvara Ikskul von Hildenbandt was the wife of the Russian ambassador to Rome who hosted soirées at her home in Moscow during the 1880’s with eminent writers and artists as her guests, one of whom was Ilya Repin. She was the hostess of a noisy and motley literary salon, who herself used to write a lot in her youth. Pavel Tretyakov commissioned Repin to paint a portrait of the salonnière in 1889. On receiving this commission, Repin wrote to Tretyakov:

“…The Baroness is in rapture at the thought that her portrait will be in such a famous gallery……..She is an interesting model and poses like a statue…”

The almost life-size portrait is brought to life by Repin’s use of red and black. The artist has captured the detail of the lady’s attire with great skill, from the ruched skirt and tightly cinched blouse with its high-necked bow to the curious points and folds of the headdress. There is a concealment of flesh with just the hands and face bared and even the latter is partially veiled, partly concealing her eyes. Yes, the pose is quite static but one cannot deny it is a dynamic one. In 1917 following the Revolution, the baroness was forced to leave her mansion and flee to Finland and later Paris.

Ilya Yefimovich Repinwas was, without doubt, the most renowned Russian artist of the 19th century. In this blog I have just concentrated on some of his portraiture which can be found at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow but he is probably best remembered for his realist paintings such as his 1873 work Barge Haulers on the Volga

https://mydailyartdisplay.wordpress.com/2012/07/05/barge-haulers-on-the-volga-by-ilya-repin/

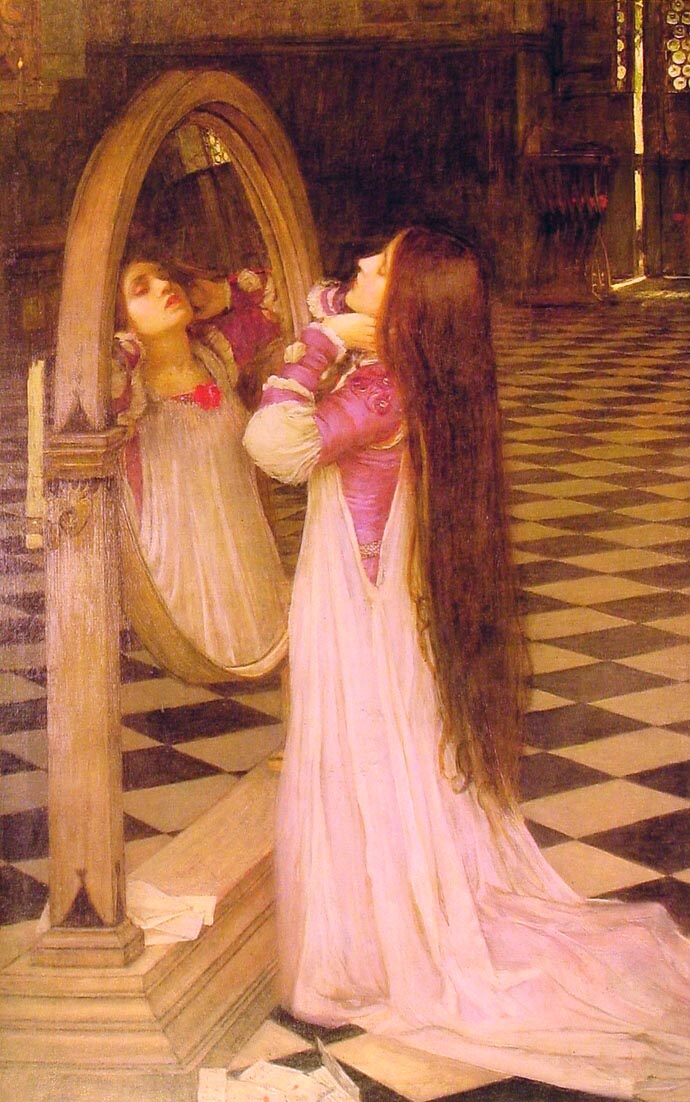

It is important to look carefully at the mirror to see how Waterhouse has carefully chosen what is reflected in it. It reflects the arches of the tower’s windows creating a “heart” shape which symbolises what the lady dreams of – love and to be loved. But, like the mirror itself, this will soon be shattered. The river is reflected in the mirror reminding us that this is the ladies escape route. Camelot is also reflected in the mirror. This is where Sir Lancelot rides to and from. The reflection at the bottom of the mirror is of the two young lovers. There is a look of frustration on the lady’s face, no longer satisfied by her weaving. Frustrated by her lack of freedom. The sight of the two lovers in the mirror is frustrating her. She realises she must escape captivity and does not fear the consequences.

It is important to look carefully at the mirror to see how Waterhouse has carefully chosen what is reflected in it. It reflects the arches of the tower’s windows creating a “heart” shape which symbolises what the lady dreams of – love and to be loved. But, like the mirror itself, this will soon be shattered. The river is reflected in the mirror reminding us that this is the ladies escape route. Camelot is also reflected in the mirror. This is where Sir Lancelot rides to and from. The reflection at the bottom of the mirror is of the two young lovers. There is a look of frustration on the lady’s face, no longer satisfied by her weaving. Frustrated by her lack of freedom. The sight of the two lovers in the mirror is frustrating her. She realises she must escape captivity and does not fear the consequences.