My eight-week holiday in the sun on the picturesque Algarve coast has come to an end and I have now returned to the gales and rain back home. Whilst away I had no real quiet time to concentrate on writing another blog on art but was full of ideas, which I can now work on.

A few months ago when I was in Moscow I was fortunate to visit the Tretyakov Museum and look at their wonderful collection. I started that series of blogs by talking about the founder of the Museum before looking at some of the works in the collection. Whilst in the Algarve I took a train up to Lisbon and spent three days in the capital. During that time I visited the large Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in the heart of the city. It was an incredible museum in a tranquil and beautiful setting in the heart of the Portugeuse capital. So who is Calouste Gulbenkian?

A few months ago when I was in Moscow I was fortunate to visit the Tretyakov Museum and look at their wonderful collection. I started that series of blogs by talking about the founder of the Museum before looking at some of the works in the collection. Whilst in the Algarve I took a train up to Lisbon and spent three days in the capital. During that time I visited the large Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in the heart of the city. It was an incredible museum in a tranquil and beautiful setting in the heart of the Portugeuse capital. So who is Calouste Gulbenkian?

Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian was a very wealthy businessman, art collector, and philanthropist of Armenian descent, who was born on March 23rd, 1869 in Üsküdar, or as we know it, Scutari, a large and densely populated district on the Asian side of Istanbul.

He was the eldest of three sons of Sarkis and Dirouhie Gulbenkian. His father was an Armenian oil importer/exporter who was heavily involved in the oil industry. Sarkis’ wealth came from his ownership of several oil fields in the Caucasus around Baku.

Young Carnouste Gulbenkian commenced his education attending the local Aramyan-Uncuyan Armenian school. He then attended the Lycée Saint-Joseph a private high school located in Istanbul. His father believed that his son’s ability to speak French fluently would be important in later life and so, in 1884, when Calouste was fifteen-years-old, his father had him attend the Ecole de Commerce in Marseille where he studied basic business skills, honed his ability to speak French and in the evenings began to learn English. On returning to Istanbul, Calouste continued his studies at the prestigious American Robert College and completed his studies with a diploma in engineering. Following his academic success, his father sent him to London and had him enrolled at the Kings College School to study petroleum engineering. Once again Calouste excelled and in 1887, at the age of eighteen, he earned himself an associateship of the Department of Applied Sciences an honour bestowed upon him for winning the second and third year prizes in physics and the third year prize in practical physics.

In December 1887 Calouste returned home to Istanbul. In September 1888 he travelled to Eastern Europe and the Azerbaijan capital of Baku via Batumi and Tiblisi, to learn about the Russian oil industry. Three years later in 1891, he published a book about his month-long journey of discovery entitled La Transcaucasie et la péninsule d’Apchéron; souvenirs de voyage (“Transcaucasia and the Absheron Peninsular – Memoirs of a Journey”) and parts of it appeared in the Revue des deux Mondes, the French language monthly literary, cultural and political affairs magazine.

In December 1887 Calouste returned home to Istanbul. In September 1888 he travelled to Eastern Europe and the Azerbaijan capital of Baku via Batumi and Tiblisi, to learn about the Russian oil industry. Three years later in 1891, he published a book about his month-long journey of discovery entitled La Transcaucasie et la péninsule d’Apchéron; souvenirs de voyage (“Transcaucasia and the Absheron Peninsular – Memoirs of a Journey”) and parts of it appeared in the Revue des deux Mondes, the French language monthly literary, cultural and political affairs magazine.

Another Armenian oil baron and colleague of Calouste’s father was Ohannes Essayan who had five children, one of whom was a daughter, Nevarte. Calouste and Nevarte became friends. According to Jonathan Conlin’s biography, Mr Five Per Cent: The many lives of Calouste Gulbenkian, the world’s richest man, Calouste fell in love with Nevarte whilst the two were playing dominoes, one summer’s day in 1889, at her parents house in the Turkish town of Bursa. Calouste was twenty and Nevarte was a mere fourteen years old. Because of Nevarte’s young age the couple were continually being watched and chaperoned when they were together. Even the writing to each other was difficult lest the missives fell into the hands of Nevarte’s parents. To give an idea of how difficult things were between the two young people one only has to look at an old love letter to Calouste written by Nevarte. In it, she worries about their love being discovered. She wrote:

“…Forgive me, my friend, for not going to the garden today. Yesterday afternoon, Dad was looking at me in such a strange way that I feared he suspected something. He forbade me to go out with that girl, saying that she is too young to accompany me. So don’t expect to see me in the garden again. See you in B [uyuk] D [ere] – if my friend goes there. I think we’ll see each other at the latest in a month. Oh, my friend, I know it is useless to remind you of your promise, but, for God’s sake, don’t forget your vow not to reveal to anyone anything that happened between us […] Au revoir , your faithful friend . If I seem cold to you, if and when I go to B [uyuk] D [ere], please ignore it, it will be to mitigate any suspicions. Forgive me this doodle and love me. If you have anything to say to me, you can write it on a piece of paper and give it to this girl, she doesn’t know French. Destroy this paper. Cheers…”

Both Calouste and Nevarte’s parents believed Nevarte too young to marry and so the youngsters had to wait a further three years before they married. In 1892 Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian married Nevarte Adèle Essayan in London. She was 17 and her husband 23. The couple went on to have a son, Nubar Sarkis, born in Istanbul in 1896 and their daughter, Rita Sirvate, was born in London in 1900.

Calouste Gulbenkian, despite his wealth and prestige was forced to move home due to wars and conflicts. In 1896 he and his family had to hastily flee the Ottoman Empire by steamship, during the Hamidian Massacres, which lasted almost three years, during the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the anti-Armenian sentiment in the country, which led to the persecution and killing of thousands of Armenians. The Gulbenkian family landed in Alexandria, Egypt where they temporarily settled. In later years, Calouste and his family spent time living in London and Paris. However, in April 1942, during the Second World War Gulbenkian who had been living in France, decided to seek refuge in a neutral country. For Calouste, the choice lay between Switzerland and Portugal. Gulbenkian decided on Portugal because of its geographical situation for, if necessary, he could easily escape by sea to the United States. He also favoured Portugal as it had a favourable tax regime, a stable society and he believed he would be able to avoid the prying media in places such as London and Paris. He remained there until his death in 1955. Calouste felt the Portugeuse people were very welcoming he praised the country’s hospitality, which he said he had never felt the like anywhere else.

Gulbenkian had amassed a great fortune from his businesses in the oil industry. With his vast wealth Gulbenkian took pleasure in purchasing works of art whether it be paintings, furniture, porcelain, or jewellery, dating from antiquity to the 20th century, in total over six thousand items. He acquired his first painting in April 1899, an oil painting entitled Versailles by Giovanni Boldini. His wide-ranging collection covers various periods and areas: Egyptian, Greco-Roman, Islamic and Oriental art, old coins and European painting and decorative arts. Although many works of art in Gulbenkian’s collection were once in many museum across the world, after his death, and following long-running discussions with the French Government and the National Gallery in Washington, the entire collection was brought to Portugal in 1960, where it was exhibited at the Palace of the Marquises of Pombal from 1965 to 1969. Then, on July 18th, 1956, a year after his death, the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, part of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, was opened in the Portugeuse capital. It had been specifically built to house his collection. Gulbenkian derived considerable pleasure from his collection, which he referred to as his “children”.

The Gulbenkian Museum is now looked upon as one of the best museums in Portugal. There are two buildings. One houses The Founder’s Collection which has works ranging from Antiquity to the early 20th century, including paintings by the great masters such as Rubens, Rembrandt, Turner, and Degas. The other building houses the Modern Collection which contains more than ten thousand works and is considered to be the most complete collection of modern and contemporary Portuguese art. Tour the museums and see how the Gulbenkian Museum can take you from Ancient Egypt to the present day across its two collections.

The Calouste Gulbenkian Museum is set in one of the most emblematic modern gardens in central Lisbon, which is open all year round and offers visitors a great sense of tranquillity. When I visited there, hundreds of students were relaxing on the grass in the sunshine and being besieged by hungry ducks which had emerged from their large lake looking for tasty food that the young people were lunching upon.

In my next blogs I will look at some of the paintings which I saw when I visited the Gulbenkian Founder’s Collection.

António was born in Porto in a neighbourhood which was populated by many artists and it was with him mixing in their company that he fell in love with art. He studied art at university and achieved a degree in Fine Arts. He later taught art and eventually became a professional artist. He moved to the Algarve in 2009 and founded his studio in Silves, which backs on to the Silves railway station. He says that the name he gave the studio, O Templo do Tempo, is his perception of art because he always felt that when something is truly art, it belongs to the past, present, and future – art, he says, is timeless.

António was born in Porto in a neighbourhood which was populated by many artists and it was with him mixing in their company that he fell in love with art. He studied art at university and achieved a degree in Fine Arts. He later taught art and eventually became a professional artist. He moved to the Algarve in 2009 and founded his studio in Silves, which backs on to the Silves railway station. He says that the name he gave the studio, O Templo do Tempo, is his perception of art because he always felt that when something is truly art, it belongs to the past, present, and future – art, he says, is timeless.

The mural on the north wall, to the left of the Hearing Room shows King John of England sealing and granting Magna Charta (the Great Charter) in June 1215 on the banks of the Thames River at the meadow called Runnymeade. His reluctance to grant the Charter is shown by his posture and sullen countenance. But he had no choice. The barons and churchmen led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, forced him to recognize principles that have developed into the liberties we enjoy today. King John, out of avarice, greed or revenge, had in the past seized the lands of noblemen, destroyed their castles and imprisoned them without legal cause. As a result, the noblemen united against the king. Most of the articles in Magna Charta dealt with feudal tenures, but many other rights were also included.

The mural on the north wall, to the left of the Hearing Room shows King John of England sealing and granting Magna Charta (the Great Charter) in June 1215 on the banks of the Thames River at the meadow called Runnymeade. His reluctance to grant the Charter is shown by his posture and sullen countenance. But he had no choice. The barons and churchmen led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, forced him to recognize principles that have developed into the liberties we enjoy today. King John, out of avarice, greed or revenge, had in the past seized the lands of noblemen, destroyed their castles and imprisoned them without legal cause. As a result, the noblemen united against the king. Most of the articles in Magna Charta dealt with feudal tenures, but many other rights were also included. The mural on the west wall over the entrance to the Hearing Room depicts an incident in the reign of Caesar Augustus Octavius. The Roman writer Seutonious tells of Scutarious, a Roman legionnaire who was being tried for an offense before the judges seated in the background. The legionnaire called on Caesar to represent him, saying: “I fought for you when you needed me, now I need you.” Caesar responded by agreeing to represent Scutarious. Caesar is shown reclining on his litter borne by his servants. Seutonious does not tell us the outcome of the trial but leaves us to surmise that with such a counsellor he undoubtedly prevailed. The mural represents Roman civil law, which is set forth in codes or statutes, in contrast to English common law, which is based not on a written code but on ancient customs and usages and the judgments and decrees of the courts which follow such customs and usages.

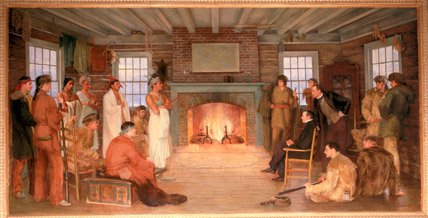

The mural on the west wall over the entrance to the Hearing Room depicts an incident in the reign of Caesar Augustus Octavius. The Roman writer Seutonious tells of Scutarious, a Roman legionnaire who was being tried for an offense before the judges seated in the background. The legionnaire called on Caesar to represent him, saying: “I fought for you when you needed me, now I need you.” Caesar responded by agreeing to represent Scutarious. Caesar is shown reclining on his litter borne by his servants. Seutonious does not tell us the outcome of the trial but leaves us to surmise that with such a counsellor he undoubtedly prevailed. The mural represents Roman civil law, which is set forth in codes or statutes, in contrast to English common law, which is based not on a written code but on ancient customs and usages and the judgments and decrees of the courts which follow such customs and usages. The mural on the south wall portrays the trial of Chief Oshkosh of the Menominees for the slaying of a member of another tribe who had killed a Menominee in a hunting accident. It was shown that under Menominee custom, relatives of a slain member could kill his slayer. Judge James Duane Doty held that in this case territorial law did not apply. He stated:

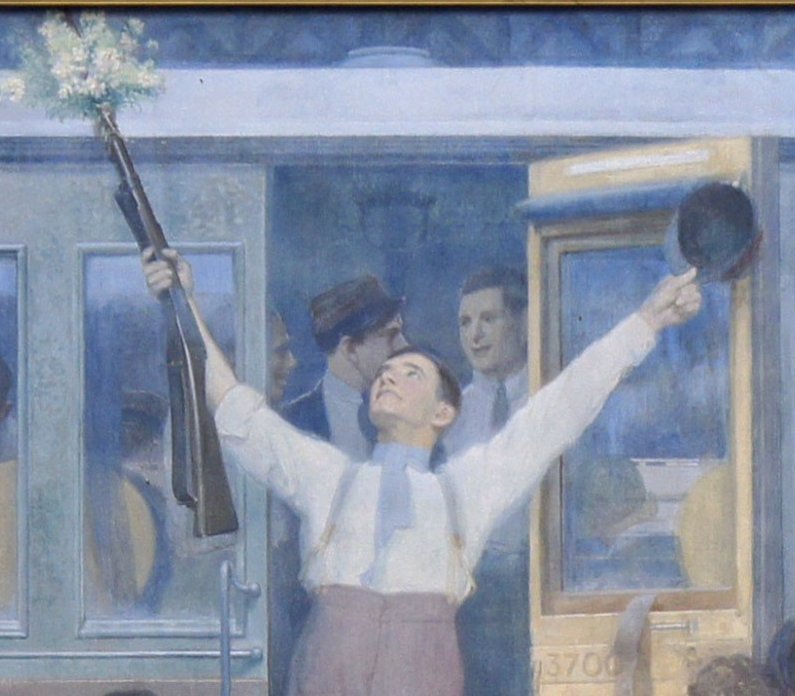

The mural on the south wall portrays the trial of Chief Oshkosh of the Menominees for the slaying of a member of another tribe who had killed a Menominee in a hunting accident. It was shown that under Menominee custom, relatives of a slain member could kill his slayer. Judge James Duane Doty held that in this case territorial law did not apply. He stated: The fourth mural, which is actually the first one that is visible on making an entrance to the Supreme Court Room, and is Albert Herter’s rendition of the signing of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. George Washington is shown presiding. On the left, Benjamin Franklin is easily recognizable. On the right, James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” is shown with his cloak on his arm. Although he was in France at the time, Thomas Jefferson was painted into the mural because of his great influence on the principles of the Constitution. The painting hangs above the place where the seven member Wisconsin Supreme Court sit to hand down their decisions. The mural’s position above the bench is symbolic that the Supreme Court operates under its aegis and is subject to its constraints. The United States Constitution has served us well for more than 200 years. This mural shows our indebtedness to federal law.

The fourth mural, which is actually the first one that is visible on making an entrance to the Supreme Court Room, and is Albert Herter’s rendition of the signing of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. George Washington is shown presiding. On the left, Benjamin Franklin is easily recognizable. On the right, James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” is shown with his cloak on his arm. Although he was in France at the time, Thomas Jefferson was painted into the mural because of his great influence on the principles of the Constitution. The painting hangs above the place where the seven member Wisconsin Supreme Court sit to hand down their decisions. The mural’s position above the bench is symbolic that the Supreme Court operates under its aegis and is subject to its constraints. The United States Constitution has served us well for more than 200 years. This mural shows our indebtedness to federal law.

The mural on the left was a scene from the court case against a local magistrate, Samuel Sewall. In 1692 a small group of men and women of Salem were arrested for bewitching their neighbours. Samuel Sewall, a local magistrate, was a member of the court that ultimately sentenced nineteen people to be hanged. The tragedy was realised several months later: those still being held were released. In the mural, Sewall is seen standing in Old South Church in Boston with his head bowed as his confession and prayers for pardon are read aloud.

The mural on the left was a scene from the court case against a local magistrate, Samuel Sewall. In 1692 a small group of men and women of Salem were arrested for bewitching their neighbours. Samuel Sewall, a local magistrate, was a member of the court that ultimately sentenced nineteen people to be hanged. The tragedy was realised several months later: those still being held were released. In the mural, Sewall is seen standing in Old South Church in Boston with his head bowed as his confession and prayers for pardon are read aloud.

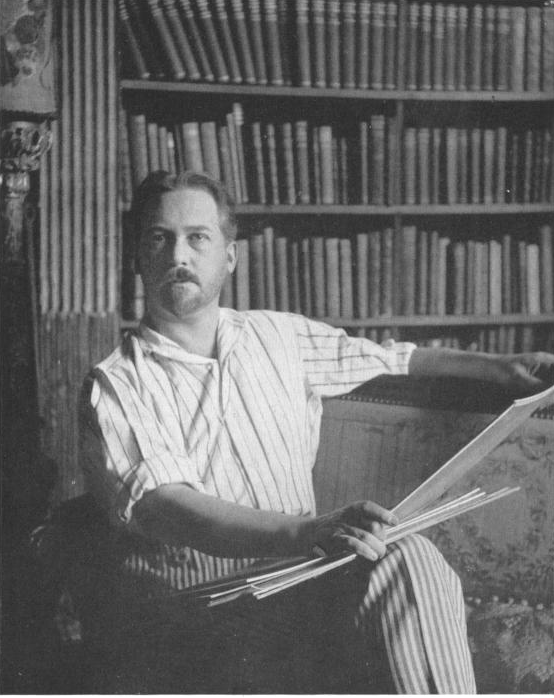

While her father was a prolific artist, his daughter’s artistic output was much more meagre for one has to remember she was a wife and a mother. She was married at the age of twenty-one and became a mother when she was twenty-two and so the output of her work was severely restricted by her responsibilities as a wife and a mother.

While her father was a prolific artist, his daughter’s artistic output was much more meagre for one has to remember she was a wife and a mother. She was married at the age of twenty-one and became a mother when she was twenty-two and so the output of her work was severely restricted by her responsibilities as a wife and a mother.

Curinier in his 1899 Dictionnaire National Des Contemporains (National dictionary of present-day people) wrote of Luigi Loir:

Curinier in his 1899 Dictionnaire National Des Contemporains (National dictionary of present-day people) wrote of Luigi Loir:

In one of the volumes of Figures Contemporaines: Tirées De L’album Mariani, illustrated biographies of famous contemporary characters from 1894 to 1925, Luigi Loir’s relationship with Paris as depicted in his art was explained:

In one of the volumes of Figures Contemporaines: Tirées De L’album Mariani, illustrated biographies of famous contemporary characters from 1894 to 1925, Luigi Loir’s relationship with Paris as depicted in his art was explained:

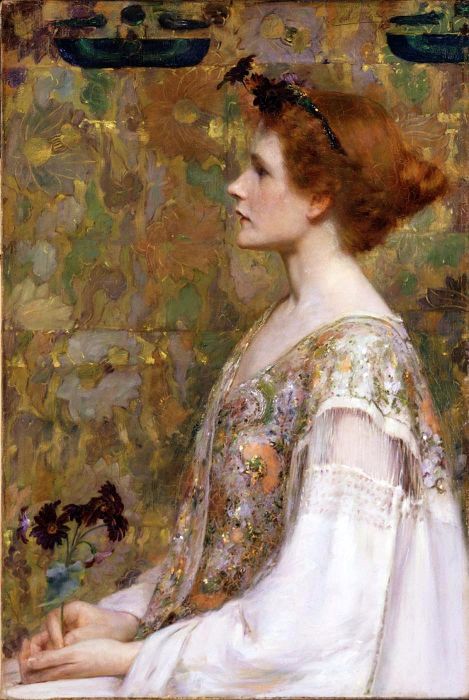

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.