One of Fern Coppedge’s later paintings, The Coal Barge, which she completed around 1940, featured the Delaware Canal. The sixty-mile canal and the coal barges, which ploughed their way down its length, were an important means of transporting anthracite coal from north-eastern Pennsylvania to Philadelphia. This barge trade lasted a hundred years and started in 1932 and in its heyday, over three thousand mule drawn boats travelled up and down this waterway carrying more than one million tons of coal every year. This mode of transport became obsolete with the transporting of coal by rail. This depiction of the canal and towpaths was a favourite depiction of many artists at the time. There was a connection between Fern and the mules, which were used to tow the barges, as her studio was in a barn which once housed the working animals.

In 1933 Fern completed a painting entitled Evening Local, New Hope which originally had the title, Five O’clock Train, which pictorially presents historical documentation of the schoolhouses which were in the New Hope-Solebury School District. The painting depicts New Hope Elementary School which can be seen on the hill off West Mechanic Street in New Hope. The building is no longer a school but is now the home of the New Hope Jewish congregation Kehilat NaHanar known locally as the “Little Shul by the River.”

Coppedge divided her time between her Boxwood home in Lumberville, her studio in the coastal town of Gloucester where she often spent summers, and a studio in Philadelphia which she used during exhibitions. In 1916 Fern spoke about her plein air painting at the Massachusetts fishing town of Cape Ann, Gloucester, and how she had many ardent onlookers. She wrote:

“…In the waters shown in my paintings, there were a number of lobster traps. The fishermen were so much interested in the development of the picture of this familiar scene that in order to have an excuse to see it they would bring me a freshly boiled lobster, and the old sea captains would entertain me with thrilling stories of stormy nights spent in their little fishing schooners on the Newfoundland Banks and the Georges…”

Fern Coppedge, back row on left)

In 1922 Fern was accepted into the all-women art society known as the Philadelphia Ten and exhibited regularly with them through to 1935. They were an exclusive and progressive group of female artists and sculptors who ignored society rules of the time by working and exhibiting together.

Coppedge once talked about her favoured methodology of painting and how she favoured working plein air to capture the essence of nature, notwithstanding inclement weather conditions:

“…I may erase most of my sketch, but after I have it the way I want it in charcoal, then I work over the entire canvas with a large brush. I use thin paint in trying to get the right value. I test different spots to see whether the scene should be painted rich or pale. Then I proceed with the actual painting using paint right from the tube. I hold the brush at arm’s length and paint from the spine. That gives relaxation…”

Pennsylvania Impressionism was an American Impressionist movement of the first half of the 20th century that was centred in and around Bucks County, Pennsylvania, particularly the town of New Hope. The movement is sometimes referred to as the “New Hope School” or the “Pennsylvania School” of landscape painting. Fern Coppedge was the only female member of The New Hope School. She was part of that art movement and devoted numerous pictures to her Bucks County environment especially her winter scenes and she would suffer for her art with her plein air painting in the sub-zero conditions. She was fascinated with the beauty of the snow. There is no doubt that the extreme cold winters challenged her devotion to plein air painting. She tried to get round this and carry on painting as long as she could by removing the back seat of her car to paint from an enclosed warm area. In cold windy conditions she would often tie her canvases to trees to fight off the wind and would wear her unfashionable but fit-for-purpose bearskin coat. It was said by a local art critic for The New Hope magazine in November 1933:

“…We remember seeing Mrs. Coppedge trudging through the deep snow wrapped in a bearskin coat, her sketching materials slung over her shoulder, her blue eyes sparkling with the joy of life…”.

There was a difference between her paintings and the other New Hope Impressionists. Unlike other New Hope Impressionists, Fern Coppedge looked at the landscape scenes she was to paint with different eyes than them. Of course, the first thing she acknowledged was what the eyes saw or the true photographic image. However, she would also want an input from her imagination and how the scene felt like to her, and it was this power of imagination that led her to paint scenes with colours and tones which did not exist in reality.

An example of her differing style can be seen if you compare her depiction of Carversville with the depiction of the same place by her fellow New Hope School artist, Edward Redfield.

Often her scenes would not be topographically correct. Again, it was down to her power of imagination which countered reality and the finished result was an idealised version of the scene which was all about pleasing the artist. In her mind, the depiction was a battle between what was actually there in front of her against what she imagined should be there. Instead of depicting building using true brown and grey colours, Fern preferred to use pink and turquoise to, as if by magic, brighten facades. A travesty of art ? Maybe we should think of how nowadays we adjust photographs, using photo editing packages, to achieve, not a true result, but a result we find more pleasing ! The fact her paintings sold so well is testament that the buying public had no problem with her idealisation or colour shifts.

Fern joined “The Philadelphia Ten” in 1922 and exhibited regularly with them for the next thirteen through 1935. The Philadelphia Ten, which was founded in 1917, was both a unique and forward-thinking group of women artists and sculptors who ignored the rules of society and the art world by working and exhibiting together for almost thirty years. Their work was varied and included both urban and rural landscapes, portraiture, still life, and a variety of representational and myth-inspired sculpture. The group of local female artists started with eleven founding members, who were all alumnae of either the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts and the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (known today as Moore College of Art and Design), but over the years the membership rose to thirty artists, twenty three who were painters and seven who were sculptors.

In the summer of 1925, Coppedge travelled to Italy and immersed herself in painting local scenes. She stayed in the city of Florence, which was a base for her travels around Tuscany, ever recording pictorially the beauty of the Tuscan landscape. It is thought that during her time in Tuscany Fern was inspired to change her painting style. She began to simplify the natural elements she saw before her, often flattening them and she also became much more audacious when it came to her colour choices. One of my favourite works from this period is Coppedge’s painting entitled The Golden Arno. She had sketched views of the great Italian river as it passed through Tuscany and the painting was completed back in her home studio. Coppedge talked about this painting and how it came about:

“…From my hotel, overlooking the Arno in Florence—looking from the balcony window—I saw the Arno River flowing gently like molten gold. It was late afternoon, and lazy Italian boatmen floated past in the dark, sturdy barges, wending their way down the river. Along the opposite bank were charming old stucco houses in colours of pale and rusty yellow, rose, pink, and old red. Tiled roofs, arched doorways and deeply recessed windows, balconies, towers and turrets against the background of cypress trees—all mirrored in the waters of the Arno. Church towers and ancient castle walls patterned against the hills inspired me and thrilled me with an irresistible desire to put on canvas my impressions…”

In 1926, the painting of the Arno was included in an exhibition of The Philadelphia Ten. It received great praise from both viewers and art critics. The painting was later exhibited in exhibitions in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, and it is now regarded as one of her best works. It was also reproduced on the cover of The Literary Digest in March of 1930. The painting was acquired by her local high school, mostly likely after the school opened in 1931. Around 1934, Fern stopped exhibiting with The Philadelphia Ten and instead focused on exhibiting at her studio,

During her artistic career she received several awards including the Shillard Medal in Philadelphia, a Gold Medal from the Exposition of Women’s Achievements, another Gold Medal from the Plastics Club of Philadelphia, and the Kansas City H.O. Dean Prize for Landscape.

Coppedge died at her New Hope home on April 21st, 1951 at the age of 67. Her husband, Robert W. Coppedge, died in New Hope, Pennsylvania in 1948. The Coppedges, who were married in 1904, remained husband and wife for 44 years. Fern Coppedge was one of America’s most prolific painters, having completed over five thousand works during her lifetime. I will leave the last word on Fern Coppedge and her paintings to Arthur Edward Bye, an American landscape architect born in the Netherlands who grew up in Pennsylvania who said:

“…Man and his activities seem pleasantly remote but not absent in her landscapes. She fills them with houses and churches, lanes, bridges, and canals. They have therefore, that suggestion of human life, coloured with brightness, exuberant, which best answers the needs of most of us…”

Most of the information for this blog came from the website Pennsylvania through the eyes of Fern I Coppedge.

He completed Legend and Stories of King Arthur in 1903. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle’s novel begins with King Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.

He completed Legend and Stories of King Arthur in 1903. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle’s novel begins with King Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.

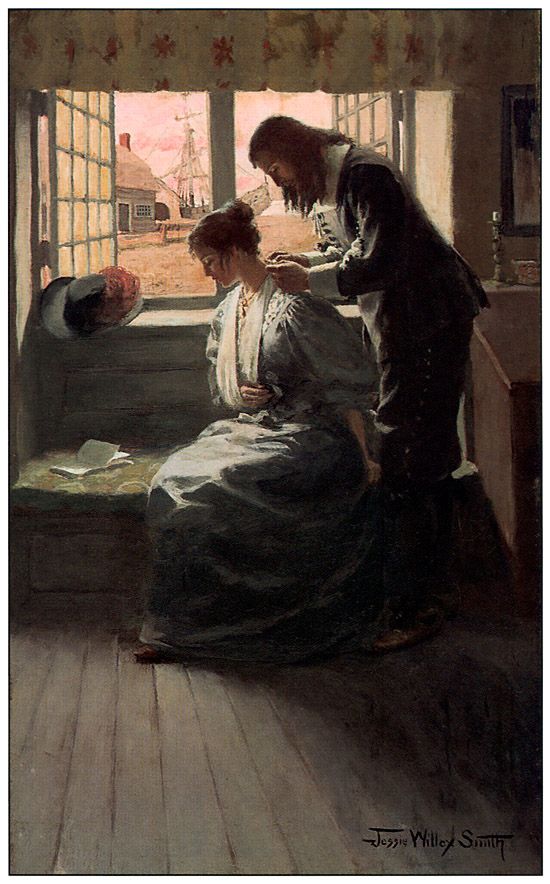

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.