Chardin was taken seriously ill, both physically and mentally in 1742. It was probable that his temporary decline in health was due to the extreme sadness he suffered due to the passing of his loved ones. Chardin and Marguerite Saintard were married in February 1731. Two months later, his father, Jean Chardin, died. Marguerite Saintard who had given birth to Chardin’s son and daughter died in April 1735 and a year later his daughter, Marguerite-Agnès, also died aged three. Chardin was appointed guardian to his son, Jean-Pierre in November 1737. Chardin and his son were now living in a Paris apartment in rue du Four, sub-let to him by his mother. Apart from the deaths of members of his family, the other aspect of his life which probably contributed to his illness was his dire financial situation. He owed his mother for the money she had loaned him after his wife died and he had run up debts with his supplier of painting materials. His financial position worsened even further when his mother, Jeanne-Françoise, died in November 1743.

Chardin needed to improve his financial position. He had already decided to move away from still-life paintings and concentrate on genre works which once made into engravings provide him with much-needed income from the popular prints. Still, money or lack of it, remained a problem for forty-five-year-old Chardin but this was all to change in 1744 when he married his second wife, Françoise-Marguerite Pouget at Saint-Sulpice Church on November 26th 1744. Françoise was the thirty-seven-year-old wealthy widow of Charles de Malnoé and eight years Chardin’s junior. Françoise was simply a God-send to Chardin. She saved him from abject poverty and helped him manage his correspondence and his responsibilities on behalf of the Salon, which included arranging the exhibitions and acting as treasurer, from 1755, during which time he was tasked to manage the Académie accounts. Françoise-Marguerite Pouget gave birth to Chardin’s daughter, Angélique-Françoise in October 1745 but sadly the baby died in April 1746.

Françoise-Marguerite Chardin appeared in a number of her husband’s works, one being The Sertinette or The Bird Organ which he completed in 1751 and was exhibited at that year’s Salon as Lady Varying Her Amusements. A serinette was a small barrel organ originally designed for teaching cage birds to sing. The painting is housed at the Louvre which acquired it in 1985. It was the first Royal order passed to Chardin, originally commissioned by Le Normante de Tourneheim, keeper of the King’s estates, for Louis XV but two years later, was gifted by the king to the Marquis de Vandières, the brother of Mme de Pompadour, the king’s favourite. In the painting we see a lady, modelled by Chardin’s wife, Françoise, with the help of a “serinette”, teaching the caged bird to sing. The setting for the painting is a bourgeois interior. The woman wears a cap tied under neck and a delicate white scarf-like narrow piece of clothing, worn over her shoulders, similar to a stole and known as a tippet. The tippet she wears partially covers a dress embroidered with flowers. The lady is seated and on her knees is the serinette which she activates by turning the handle. At the left of the painting we see a bird’s cage resting on a pedestal. The pedestal has a crossbar which allows one to fix a screen to protect the serin, a small finch-like bird, from the light and from distractions which would hamper it from learning a tune. It was with the help of this salon instrument that the ladies of the “good” society taught their caged birds to sing. In front of the woman, we can see a large work bag which contains her embroidery.

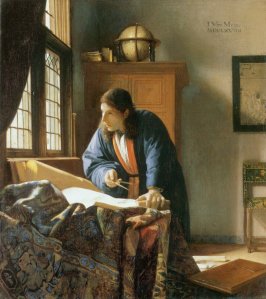

Light streams into the room through the window to the left similar to depictions seen in seventeenth century Dutch paintings – think Vermeer for example, and they obviously had an influence on Chardin.

The Frick Collection, New York

Another version of the painting is in the Frick Collection in New York, which came from the collection of Dominique-Vivant Denon, the director of the Musée Napoléon and bought by the New York gallery in 1926. There is one major difference between the two versions and I will leave you to spot it!

Chardin’s 1746 painting Domestic Pleasures also featured his second wife. The painting was commissioned by Lvise Ulrike, the sister of Frederick the Great of Russia and the wife of Adolf Frederick the Crown Prince of Sweden and the country’s future king. However, the commissioning was far from straight forward. Lvise Ulrike was a great fan of Chardin’s paintings and wanted him to paint two works and she gave him the titles of them to be The Strict Upbringing and The Gentle, Subtle Upbringing. Unfortunately for her, Chardin was a slow painter which in a letter dated October 1746, he stated:

“…I take my time because I have developed the habit of not leaving my paintings until, to my eyes, there is nothing more to add…”

Chardin’s assertion that it was diligence and being a perfectionist were the reasons for the long time he took on each painting was challenged by others who put it down to his laziness. The princess was however not amused by this slow pace. Bizarrely Chardin finished the two paintings in 1746 but the subjects had nothing to do with the titles supplied by the princess. They appeared at the 1746 Salon entitled Domestic Pleasures and The Housekeeper and were subsequently given to Lvisa via the Swedish ambassador in Paris in February 1747.

My last offering of a Chardin painting, featuring his wife, Françoise-Marguerite Pouget, is his pastel work entitled Portrait of Madame Chardin, née Françoise-Marguerite Pouget which he completed in 1775 when he was seventy-six and which can now be seen in the Louvre. A year later he repeated the portrait, which is now housed in the Art Institute of Chicago. Before us we see the face of Chardin’s second wife, sixty-eight-year-old Marguerite Pouget. Her face is wrapped to the eyes in an almost nun-like headdress, a head covering which often featured in Chardin’s paintings. Her forehead has an ivory pallor. Look how a shadow is cast by the headdress and the daylight on her temple is filtered through its linen material. Her mouth is closed tightly and she is not smiling. Her gaze is frosty. There is a dullness about her eyes. We detect wrinkles around her eyes. Chardin has managed to create all the indicators of old age. Chardin’s use of colours is masterful. The whiteness of her face is achieved with pure yellow and the pallid face has no white in it at all. The pure white cap is made solely of blue. The art critics loved the portrait. The eighteenth-century writers, publishers, literary and art critics, the brothers Edmond, and Jules de Goncourt wrote:

“…it is in the portrait of his wife that he reveals all his ardour, his vitality, the strength and energy of his inspired execution. Never did the artist’s hand display more genus, more boldness, more felicity, more brilliance than in this pastel. With what a vigorous, dense touch, with what freedom and confidence he wields his crayon; liberated from the hatching that previously damped his voice or obscured his shadows. Chardin attacks the paper, scratches it, presses his chalk home……To have represented everything in its true colour without using the real shade, this is the tour de force, the miracle that the colourist has achieved…”

Chardin produced many genre paintings in the late 1730’s and early 1740’s which depicted female servants carrying out their household duties. There are three versions of The Turnip Peeler which he completed around 1738. One is housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington whilst one can be found in the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen in Munich. The third version was previously in Berlin, acquired for Frederick II of Prussia but which is now lost. The Washington version was exhibited at the 1739 Salon by Chardin and bought around that time by the Austrian ambassador, Prince Joseph Wenzel of Liechenstein. It became part of the Washington National Gallery collection in 1952. Before us we see a large woman sitting slightly hunched on a chair, knife in hand, about to peel a turnip. She gazes out blankly, lost in thought. She is surrounded by other vegetables such as a large pumpkin, some cucumbers and a bowl of water which contains the previously scraped turnips. In front of her we see a copper cauldron and a saucepan which is leaning against a bloodstained butcher’s block, in which a meat clever has been driven. This genre piece by Chardin is not one which has an anecdotal element to it, neither has it any social comment about the plight of servants.

A painting which has connections with The Turnip Peeler is The Return from Market. Once again, three versions of this painting exist. One, dated 1738, is in Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada, and was presented to the Salon in 1739. One is at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin and is dated 1738, and the third is housed in The Louvre. It is believed that the version held in Berlin was a companion piece to The Turnip Peeler, with the two being acquired by Frederick the Great in 1746. This painting unlike its companion piece still survives, but only just, as it was found in the park at Charlottenburg after the Schloss was pillaged by Austrian troops in 1760. Since that time this work by Chardin has never left Berlin. An engraving by François-Bernard Lépicié was made from the Louvre version. Lépicié made engravings of a number of Chardin’s paintings and prints from the engravings were a great source of income for the artist. When the painting was exhibited at the 1739 Salon it received great critical acclaim. The French literary brothers, Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, wrote about the work stating:

“…the colours placed side by side give the painting the appearance of a tapestry in gros point…”

While the writer Henri de Chennevières was even more enthusiastic when he wrote about Chardin’s use of colour:

“…the milky whites of the woman’s skirt, the unique faded blues of the apron….., the floury, golden crust on the loaves of bread. And the two bottles on the floor, the red seal on one of them echoing the ribbon on her sleeve…”

My final two paintings by Chardin in this blog are his small pendant works, (49 x 39cms), The Diligent Mother and Saying Grace, both of which were completed in 1740. Chardin gave both works to Louis XV in the November following their showing at the Salon and are now housed at The Louvre. The Diligent Mother was the less famous of the two works and depicts a young mother, wearing pink slippers and blue stockings, her scissors hanging at her waist as she and her daughter inspect a piece of embroidery. In the foreground, by her, we see a wool winder and skein with coloured balls of wool inside the base of it. A bobbin can be seen lying on the floor as well as a box which acts as a pin cushion, next to which is curled-up pug. To the extreme right we see a red fire screen, while behind the mother stands a large green folding screen which prevents the light from the half-open door entering the room. The work was considered to be a genre piece in which a well-to-do middle-class mother shows the daughter a mistake she has made in her tapestry. One other interesting fact about this work was when an engraving was made of it by the engraver François-Bernard Lépicié, he added lines of moralistic verse to it so as to explain what was depicted:

“…A trifle distracts you my girl

Yesterday this foliage was done

See from each stitch you have made

How distracted your mind is from work

Believe me, avoid laziness

Remember this one simple truth

That hard work and wisdom together

Are more valued than beauty and wealth…”

Were these salutary words approved by Chardin? Are they Chardin’s or Lépicié’s words?

The final Chardin painting for today’s blog is entitled Saying Grace and is one of his most celebrated and most popular of his works. The theme of the painting is prayer before meals and was one of the most famous works by Chardin but when it was shown at the 1740 Salon it received very little praise. However, along with its pendant piece, The Diligent Mother, it was given to Louis XV. It remained in the royal collections until the French Revolution; it then entered the Muséum Central des Arts, which would later become the Louvre, in 1793. It was largely forgotten until the nineteenth century when Chardin was “rediscovered”. It was then that the work was hailed as being emblematic of a morally upright, industrious social class and was often contrasted to the debauched, wasteful lifestyle of the aristocracy. Chardin in this tender work depicting a mother teaching her children to pray highlights commendable and hidden qualities and like many of his genre works, once again depicts the satisfied life which comes from a sense of duty, unlike the Rococo painters of the time, such as François Boucher, who depicted the dalliance and flirting of the nobility and upper-classes at their garden luncheons, and moonlit promenades.

In my final blog about Chardin I will be looking at his latter days and his works of portraiture.