Of my featured artist today, the Dutch Golden Age writer and poet Theodorus Schrevelius wrote in his 1648 book about the history of Haarlem entitled Harlemias:

“…There also have been many experienced women in the field of painting who are still renowned in our time, and who could compete with men. Among them, one excels exceptionally, Judith Leyster, called “the true Leading star in art…”

Judith Jans Leyster was born in Haarlem in July 1609. She was the eighth child of Jan Willemsz Leyster who was a cloth maker and owner of a local brewery, which was called Ley-ster (guide or leading star). It is thought that her initial artistic tuition came from Frans Pieter de Grebber. De Grebber, a member of the local painters’ guild, Haarlem Guild of St Luke, was a landscape artist and portraitist, who also designed tapestries. The reason for this belief is that the chronicler of life in Haarlem at that time, Samuel Ampzing, mentioned Judith Leyster in his 1628 book about life in Haarlem, Beschrijvinge ende Lof der stad Haelem in Holland. He commented that Leyster, then 19 years old, was a painter who had “good and keen insight”. It was interesting to note that he also made the comment: “Who has ever seen paintings by a daughter?” which alluded to the fact that it was very unusual for a female to become a professional painter and furthermore, in 1633, she was one of only two females in the 17th century who had been accepted as a master in the Haarlem Guild of St Luke. The first woman registered was Sara van Baabbergen, two years earlier.

It was around this time that Judith’s family left Haarlem and moved some forty kilometres to the southwest and went to live in Vreeland, a town close to the provincial capital Utrecht. Utrecht in the 1620’s was the home of the group of artists known as the Utrecht Caravaggists. These painters, such as Dirck van Baburen, Hendrick ter Brugghen, and Gerrit van Honthorst had spent time in Rome during the first two decades of the 17th century and, in the Italian capital, it was a time when Caravaggio’s art was exerting a tremendous influence on all who witnessed his works and by the early 1620s, his painterly style of chiaroscuro, was wowing the rest of Europe. Whether Judith Leyster mixed with these painters or just picked up on their style is in doubt as the family stayed in the Utrecht area less than twelve months, moving to Amsterdam in the autumn of 1629 but two years later Judith returned to her home town of Haarlem.

It is known that she met Frans Hals when she was in Haarlem but although many of Leyster’s work resembled Hals’ work, both in style and genre, art historians are not in agreement as to whether she was ever actually Hals’ pupil or simply an admirer. Leyster’s paintings were secular in nature and she never painted any religious works. Although she is known to have painted a couple of portraits she was, in the main, a genre painter, recording on canvas the life of everyday people. They were, generally speaking, joyous in their depiction and were extremely sought after by wealthy merchants.

Her famous self-portrait was completed around 1630 when she was twenty-one years of age and could well have been her entrance piece for the Haarlem Guild of St Luke’s. In the work, she is at her easel, palette and an array of eighteen paint brushes in her left hand. Her right arm is propped against the back of her chair and a brush, held in her right hand is poised ready to carry on painting the work we see on her easel. She has turned towards us. She is relaxed and seems to have broken off from painting to say something to whoever is in her studio. The first things we notice are that the clothes she is wearing. These would not be the ones she would wear when she was painting. They are too good for such a messy job to be worn by somebody who is painting. Her skilful depiction of her clothes allude to her social status and her depiction of them is a fine example of the up-to-date female fashion. Also consider, would a painter working on a painting really be clutching all eighteen of their brushes at the same time? Of course not! This is more a painting in which Judith Leyster is intent on promoting herself. Through this self- portrait she is eager to reveal herself, her painterly skills and her social standing. In this one painting she is advertising her ability to paint a merry genre scene as seen by the painting of the violin player on the easel. This depiction of a musician was similar to the one depicted in her 1630 work entitled The Merry Company, which she completed around the same time as this self-portrait. Of course this being a self-portrait it has also highlighted her ability as a portraitist. It is interesting to note that when this painting was subjected to infrared photography it was found that the painting on the easel was Leyster’s own face and so one has to presume she originally intended that this painting would be a quirky “self-portrait within a self-portrait”, but presumably, Leyster on reflection, decided to have the painting on the easel represent another facet of her painterly skills – that of a genre painter. This was her most successful and profitable painting genre with its scenes of merrymakers. It was this type of work which was extremely popular with her clientele, who wanted to be reminded of the happy and enjoyable times of life. Although Leyster was proficiently skilled as a portrait artist the art market was already crowded with popular portraitist and so, probably for economic reasons, she decided to concentrate on her genre paintings.

Around 1629 she set up a studio on her own and started to add her own signature to her works. Her signature or moniker was an unusual and clever play on her surname “Leyster”. Lei-star in Dutch means “lode star” or “polestar” a star often used by sailors to navigate by and she was often referred to as a “leading star” in the art world, and so she used this play-on-words to create a special signature: a monogram of her initials with a shooting star. She must have been successful at selling her works of art as soon she had employed three apprentices. It is interesting to note that she had a falling out with Frans Hals who had “illegally” poached one of her apprentices and the whole matter ended up in court at which time Hals was made to apologise and make a payment to her for his action.

Judith Leyster completed many genre pieces in which she portrayed people as being happy with their lot in life. Settings were often inside taverns but whereas with other Dutch artists who tended to portray the tavern dwellers with a moralistic tone around the evils of drink and the repercussions of becoming a heavy drinker, Leyster wanted to focus more on people enjoying themselves. A good example of that was her 1630 painting which is in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum entitled The Jolly Toper or The Merry Drinker which is considered to be one of her finest works.

However with this painting came the assertion by many critics that she was merely a copier of Frans Hals style of painting, such as her choice of subjects and her brushwork. Hals had completed his own painting The Merry Drinker in 1630 so I will leave you to decide whether there are more similarities between Leyster and Hal’s paintings other than the subject matter.

Although Leyster’s genre scenes would often focus on happiness and merriment with no moralistic judgement, she did occasionally focus on the darker side of life and a good example of this can be seen in her 1639 painting which is housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, entitled The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier). It is a vanitas work, meaning it is a work of art which in some way symbolises the brevity of life. In the work we see two men dressed in festive clothing having an enjoyable time drinking and smoking. The fact that they are not just celebrating but are also dressed up for the occasion has led people to believe that this merriment is taking place on the Dutch holiday of vastelaovend, which we know as Shrove Tuesday, the day before the start of Lent. This was the day when people took advantage of the last day of merrymaking before the forty days of Lent abstinence and fasting. However it is not just the two revellers that Leyster has depicted in the drinking scene, for between them we see a skeleton. The skeleton holds an hour-glass in one bony hand and a skull and a lit candle in the other. The candle both casts a shadow on the seated drinker but at the same time lights up the cavalier’s face. The skull, burning candle and hour-glass are classic symbols of a vanitas painting which have the sobering effect of reminding us of the brevity of life and the inevitability of death. There is no interaction between the drinkers and the skeleton which is probably an indication that as they have imbibed so much alcohol the thought of death never crosses their mind. Look at the expression on the face of the cavalier dressed in red. It is one of blankness and stupidity which we have often witnessed when we look into a face of a drunkard. At that moment in time, he has no concern about his own mortality. One final comment about this work is that it is a good example of how Leyster utilised a style of painting which was associated with the Italian painter Caravaggio and his Dutch followers, the Utrecht Caravaggists, whom Leyster would have seen earlier in her career. It is known as tenebrism which is where the artist has depicted most of the figures engulfed in shadow but at the same time, have some of them dramatically illuminated by a shaft of light usually from an identifiable source, such as a candle as is the case in this painting, or from an unidentifiable source, off canvas.

On a lighter note I offer you another painting with a moral, but somewhat more humorous, which Judith Leyster completed around 1635 and is entitled A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel. It is a visual joke with a moralising tale. It is one of those paintings, typical of Dutch genre scenes, in which you have to look carefully at all who and what are depicted in the painting so as work out what is going on. See if you can fathom it out.

The two main characters are a boy and a girl. The boy has a cheeky smile on his face. He has enticed the cat to join them by waving a wriggling eel which he now holds aloft, having grabbed the cat. The little girl has now grabbed the tail of the cat, which in a state of shock and fear. It is desperate to get away from the pair of young tormentors and has extended its claws and about to scratch the boy’s arm in an attempt to escape his clutches. The young girl who has a face of an older woman, admonishingly wags her finger at us – so why is she so censorious? It is believed that she is smugly warning us against foolish and mischievous behaviour alluding to the Dutch saying: ‘He who plays with cats gets scratched’. In other words he who seeks trouble will find it. Although children are depicted in this moralising scene, it is more a warning to adults about their behaviour and many Dutch artists who painted genre scenes with a moral twist frequently used children to put over their moral message.

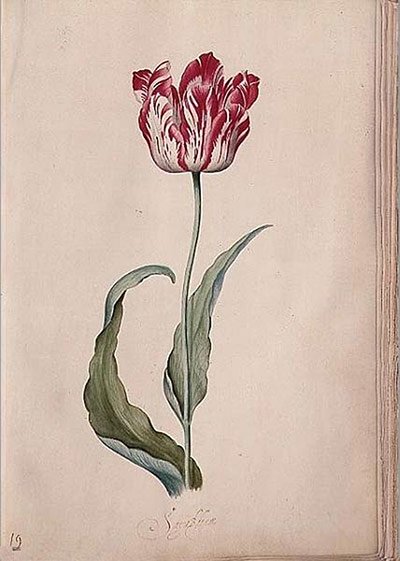

In the late 1630’s, a strange phenomenon occurred in the Netherlands, which had been brewing for a number of years. It became known as Tulpenwoede (tulip madness) which saw the price of tulip bulbs rocketing. It all began when some tulip contracts reached a level which was about 20 times the level of three months earlier. In one particular case a rare tulip known as Semper Augustus, which had been valued at around 1,000 guilders per bulb ten years earlier was fetching a price of 5,500 guilders per bulb in January 1637. This meant that one of these bulbs was worth the cost of a large Amsterdam house. Many people, who watched the rising value of the tulip bulb, wanted part of the action. People used their life savings and other assets were cashed in to get money to invest in these bulbs, all in the belief and expectation that the price of tulip bulbs would continue to rise and they would suddenly become rich. Alas as we have all seen when a thing is too good to be true, it usually is, and by the end of February 1637 the price of a tulip bulb had crashed and many people lost their savings.

from her Tulip Book

However the rising value of the tulip bulb came as a boon to floral artists for if people could not afford the actual tulips for their gardens or pots the next best thing was to have a painting of them and even better still would be to have a book full of beautiful depictions of different tulips. Judith Leyster realised that the public’s love of tulips could be advantageous for her and she produced her own book of tulips.

In 1636 Judith Leyster married Jan Miense Molenaer, another genre painter, and the two of them set up a joint studio and art dealing business. They moved to Amsterdam as the opportunity to sell their works of art was better and there was also a greater stability in the art market. Judith went on to have five children and the role of mother and housekeeper meant that her art output declined. Until recently it was thought that her artistic output had all but ceased, that was until the run-up to a Judith Leyster retrospective at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem a number of years ago when a beautiful floral still life which she painted in 1654 surfaced. It had been hidden from public view in the collection of a private collector.

Judfith Leyster and her husband remained in Amsterdam for eleven years. They then moved to Heemstede in the province of North Holland, where in 1660, at age 50, Leyster died.