In my final look at the Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla I want to show you some of his portraiture work which featured his family and finally take a look at the house in which he and his family lived and which would later become a museum in his honour.

One of the most moving family portraits by Sorolla was of his wife Clotilde, laying in bed with their new born baby, their youngest child, Elena. The painting is simply entitled Mother and was completed in 1895. His wife looks lovingly towards her daughter who is swaddled in a mass of white bedding contrasted by the artist’s yellow/green tonal shading of the bed clothes.

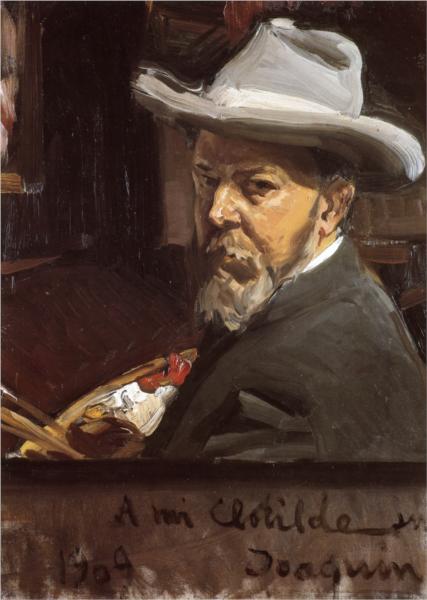

In 1901 Sorolla completed a portrait of his family entitled My Family, which somehow reminds us of Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas, where the painter showed in the background a mirror that reflects the upper bodies of the king and queen. They appear to be placed outside the picture space in a position similar to that of the viewer. In Sorolla’s painting we see his image, palette in hand, in a mirror in the background. The main figures in the painting were those of his family. His wife Clotilde stands to the left in a long red dress along with her children. Elena, the youngest, sits on the chair was five years old at the time. Their nine-year old son Joaquín sits on a stool sketching a picture of his sister whilst their elder daughter, Maria, who would have been eleven when her father completed the work, holds the board which her brother is using to support his sketch.

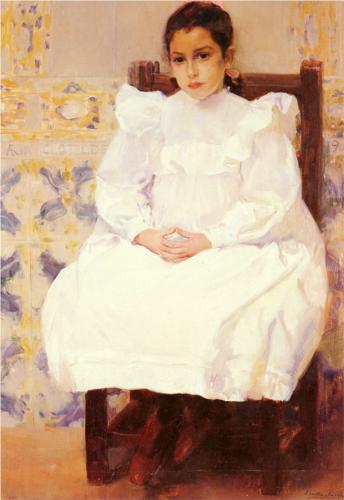

One of Sorolla’s favourite subjects was his eldest child, Maria and over the years he would capture her in many of his portraits. In 1900 he captures her sitting on a chair dressed in a white tunic with her hands entwined on her lap. The painting is entitled Maria. The whiteness of her dress is enhanced by touches of blue. In the background there is a wall with decorative and colourful tiles

Six years later he completed another two portraits of Maria. The first, entitled Maria Sick, completed in 1907 depicts his daughter sitting outside, well wrapped up in heavy but warm clothes. She was recuperating in the mountains outside of Madrid having come down with an illness. Sorolla himself was supposed to have been in Germany at this time, to be present at the one-man exhibition of his work at Berlin, Dusseldorf and Cologne organised by the Berlin gallery owner, Eduard Schulte. However Sorolla refused to leave his daughter at a time when she was so unwell.

That same year, following the recovery from her illness, her father painted another portrait of her, entitled Maria Painting in El Pardo. The work depicts his daughter seated on a hill top, close to the royal palace, painting en plein air.

However Joaquín Sorolla’s favourite muse was his beloved wife Clotilde whom he had married in 1888. She featured in a large number of his works. I particularly like the one he painted in 1910 entitled Clotilde Sitting on the Sofa. Art historians believe that the painting was influenced by the works of the American painter John Singer Sargent. His wife leans against the arm of a sofa, dressed in a full length gown.

Another beautiful painting of his lovely wife was completed that same year entitled Clotilde in Evening Dress and from it, it is plain to see that Sorolla had married a beautiful and enchanting person. We see her sitting upright in a plush, well upholstered red chair, dressed in a black evening dress with a blue flower tucked behind her ear. She is the personification of a Spanish lady.

Sorolla had a one-man exhibition in the Grafton Galleries, London in 1908 and it is whilst in London that he met Archer Milton Huntington, who was the son of Arabella Huntington and the stepson of the American railroad tycoon and industrialist Collis Huntington. Archer Huntington was a lover of the arts and the founder of the Hispanic Society of America which was based in New York. The Hispanic Society of America was, and still is, a museum and reference library for the study of the arts and cultures of Spain and Portugal as well as those of Latin America. Huntington arranges for Sorolla to have a major one-man exhibition at the Society in 1909 and it proved to be a resounding success so much so that the exhibition travelled to many American cities. Huntington then commissioned Sorolla to paint 14 large scale mural paintings, oil on canvas, depicting the peoples and regions of Spain. On receiving Huntington’s commission in 1911, Sorolla spent the next eight years travelling throughout the regions of Spain making hundreds of preparatory sketches before completing what was to become known as Vision of Spain. Sorolla was clear in his mind what Huntington expected and how he would achieve it, for he said:

“…I want to truthfully capture, clearly and without symbolism or literature, the psychology of the region. Loyal to the truth of my school I seek to give a representative view of Spain, searching not for philosophies but for the picturesque aspects of the region…”

His eight years on this project was at the expense and detriment of his other work and sadly nearing the end of this project his health began to deteriorate and in June 1920 he suffered a stroke which ended his painting career. One can only imagine how devastated Sorolla must have been not being able to paint. Three years later in August 2010 Sorolla died in Cercedilla, a small town in the Sierra de Guadarrama, north-west of Madrid. His body was taken and buried in the town of his birth, Valencia.

I cannot end this trilogy of blogs about Joaquín Sorolla without mentioning the Sorolla Museum which was the artist’s home from 1911.

It is a five minute walk from the Ruben Dario Metro station and I do urge you to visit it if you are in Madrid. You will not be disappointed.

There are so many of the artist’s beautiful paintings on show and the gardens are a delight.