In my last blog I looked at Perov’s early life and his artwork which is often categorised as critical realism because of the way his paintings focused on the peasants and how they had been let down by the Church, its clergy and the State. For one of these works he was awarded the Gold Medal by the St Petersburg Imperial Academy of Arts and also a scholarship for him to travel to Europe and study European art. He went to Paris where he spent a considerable amount of time but once again his art focused on poverty, this time, poverty in France. Perov was now moving away from his anti-clerical depictions, and his barbed narrative works which poured scorn on the Church. He now wanted to concentrate on the poor themselves and left the observer to decide on the reason for the poverty.

One of his most famous paintings, which he completed whilst in France, was one entitled Savoyard which he finished in 1863. In Perov’s painting we see a young boy sat slumped on some stone steps. The absence of any movement allows us to focus on the child without any distractions. The child is asleep. His feet stick out in front of him and this allows us to see the tattered hems of his trousers and because of the way is feet rest on the pavement we are given a view of the soles of his shoes, which are holed. The painting itself is made up of dark sombre tones of smoky blue, green and grey.

It is thought that Perov’s painting was influenced by the work of Paul Gavarni, a French engraver, who had his illustrations published in a collection of London sketches, featuring life in London at the time. The sketches and accompanying illustrations were first published as a magazine series in 1848 and later they were collected in one volume, edited by essayist and journalist Albert Smith, which was first published in Paris, in 1862, a year before Perov’s arrival in the French capital. It was entitled Londres et les Anglais. One of the sketches was the Street Beggar and its thought that Perov had this in mind when he worked on the Savoyard.

Perov’s arrival in Paris in 1863 coincided with a great upheaval in French art. The Hanging jury at that year’s Salon had been ruthless in their choice of paintings which could be admitted. Those which were cast aside were ones deemed to have not been of the quality or type they wanted. That year, the jury had been more ruthless than they had been in the past, rejecting two-thirds of paintings. This resulted in vociferous protests from the artists who had had their works rejected. It was so bad that Napoleon III stepped into the argument and placated the disgruntled artists by offering them a separate exhibition for their rejected works. It became known as the Salon de Refusés (Exhibition of rejects) and that year this exhibition exhibited works by Pissarro, Fantin-Latour, Cezanne and included Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe and Whistler’s Symphony in White,no. 1.

Perov returned home early from his European tour in 1865 and in 1866 produced a wonderful painting entitled The Arrival of the Governess at a Merchant’s House. This was a move away from his focus on poverty and more to do with the fate of women. In the painting we see a governess standing before the master of the house, a merchant who is to be her new employer. This painting depicts the awkward encounter between the governess, who has probably graduated from a school for governesses, where they are taught to act like nobility, and the merchant who has no noble blood and is the face of the nouveau riche. She presents herself well. She clutches a letter of introduction in her hands. She oozes an air of timidity and subservience, which is a trait that would be required if she was to become a member of the household. However her demure stance with head bent down is befitting that of a lady. She stands before, not only the master of the house, a bloated man, but behind him stands his family. The children of the family are to be her pupils and by the looks of them she was going to be in for a difficult time. The master of the house and his three children are dressed elegantly and the furnishings we see are fine and elegant and are part of merchant’s plan that they be elevated in status from mere merchants to something approaching nobility. Perov has changed the subject of his biting satire from the clergy of the Church to the oppressive merchant classes and the poor treatment they bestow on their employees.

The painting was purchased by thirty-four year old Pavel Tretyakov, a Russian businessman, patron of art, avid art collector, and philanthropist who gave his name to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. This work along with his Troika painting earned Perov the title of Academician.

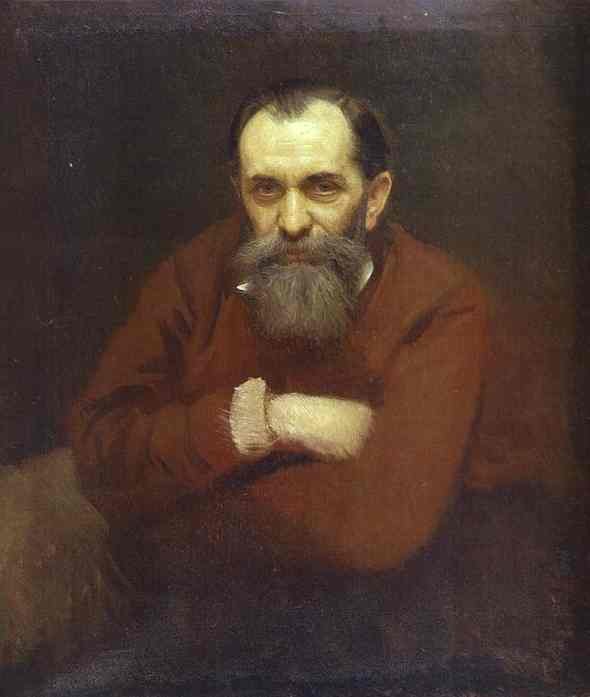

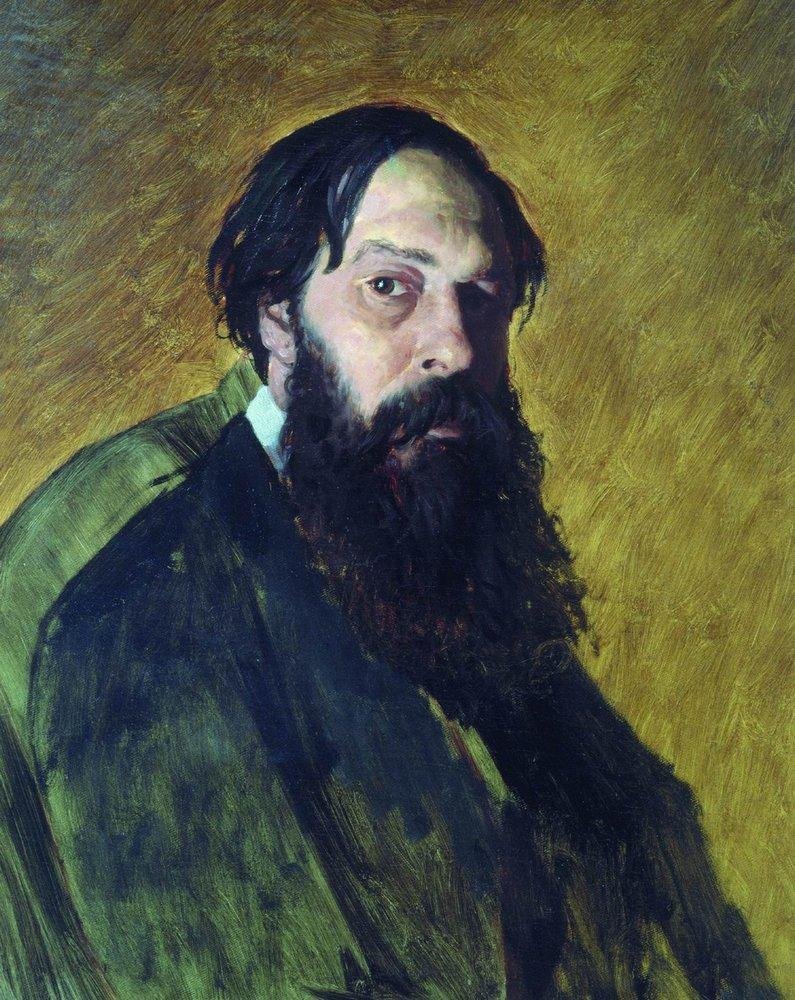

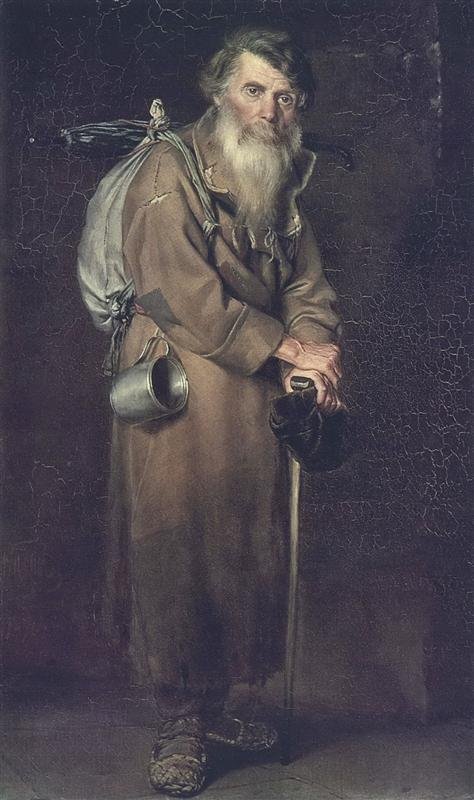

In the late 1860’s Perov began to concentrate on portraiture, initially of peasants and the title Wanderer was given to three of his works which featured peasants, all different and yet all emotive in their own way, one of which is shown above. As Perov travelled around he came across a variety of fascinating characters and he was able present them on canvas and highlight their individualism and their way of life.

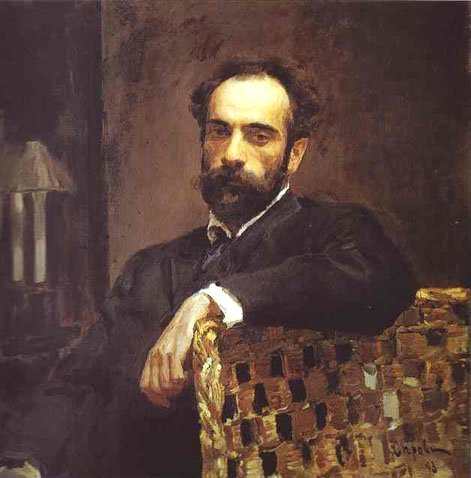

In the early 1870’s Perov’s portraiture focused on cultural greats of Russia but it is interesting to note in these next two paintings they were totally devoid of any background accoutrements which would have added a sense of vanity in the sitter. In 1872 he completed the Portrait of Dostoyevsky, a the Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist and philosopher. It was Dostoyevsky’s literary works which influenced Perov in the way they explored human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmosphere in Russia during the 19th-century.

And in 1871 he finished his Portrait of Alexander Ostrovsky, a Russian playwright who was generally thought to have been the greatest writer of the Russian realistic period, which existed against the background social and political problems. It started in the 1840’s under the rule of Nicholas I and lasted through to the end of the nineteenth century. The painting is now housed in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

In all his genre works he always managed to tug at your heart strings with his moving depictions. Another of his heart-rending scenes was completed in 1874 and was entitled Old Parents Visiting the Grave of their Son. It is said that nobody should suffer the agony of burying their children and in this work we feel the loss of the mother and father as they stand, heads bowed, at the side of the son’s grave. This painting, like many of his other works, are to be found at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Having received his academician’s degree in 1867, Perov went on in 1871 to gain the position of professor at Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. It was through Perov’s teaching at Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture that he managed to influence and nurture the young aspiring artists in his charge. Many of the great Russian artists had been taught by him or were influenced by his style of painting

As always I have the dilemma of which paintings to show you and which ones to leave out. I just hope the blog will get you to search the internet for more of his works. My final offering is one that features Perov’s sense of humour. It is in complete contrast to his works which looked at poverty and the impoverished existence of the peasant classes. It is a painting entitled Amateur which he completed in 1862. It is both humorous and fascinating. Before us we see a man slouched in a chair, chewing on the end of his maulstick, eyes narrowed as he looks at his work. His wife stands beside him holding a baby. She too is closely examining the canvas. From the way the man is dressed along with the background details of the room we gather that this is an upper-middle class couple. Another give away to the man’s social status is the way Perov has depicted him. Well dressed, highly polished shoes and overweight. Perov’s depiction of this man is similar to the master of the household, the merchant, whom he depicted in The Arrival of the Governess at a Merchant’s House- overweight, through all the food he had been able to buy and eat, whereas in most cases Perov portrayed the poor peasants as thin undernourished people.

Vasily Grigorevich Perov died of tuberculosis in Kuzminki Village which is now part of Moscow and was laid to rest at Donskoe Cemetery. He was fifty-eight years old.