In my last blog I featured a painting by Theodore Roussel entitled The Reading Girl which was at the time both controversial and newsworthy, only going to prove the old adage that there is no such thing as bad publicity. My blog today follows a similar theme, a controversial painting which had major repercussions on the artist and his career.

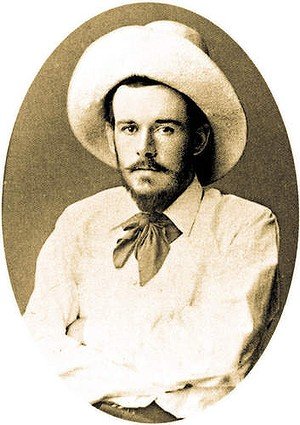

My featured artist is John Singer Sargent. He came from a very wealthy family. His grandfather was Winthrop Sargent IV, who had descended from one of the oldest colonial families. Due to a failed merchant-shipping business in Gloucester, Massachusetts, he moved his family to Philadelphia. It was in that city that John Singer Sargent’s father, Fitzwilliam Sargent became an eye surgeon. In 1850, Fitzwilliam Sargent married Mary Newbold Singer who was the daughter of a successful local merchant. In 1853 Mary gave birth to their first child, a daughter, who sadly died a year later. Sargent’s mother suffered a nervous breakdown after the death of her daughter and her husband decided that it would be better for his wife’s health to move away from Philadelphia and the sad memories and take up residency in Europe. Initially Sargent’s father’s idea was for he and his wife to stay in Europe just a short time until she was better but their life away from America extended and soon they became expatriates. He and his wife based themselves in Paris but they would often travel and stay in Florence, Rome, or Nice in the winters and in the summers they would journey to the Alps were the climate was much cooler and more pleasant. Their son John was born in January 1856 whilst they were in Florence.

Because of the nomadic lifestyle of the family and because of his determination not to stay in school, John Singer Sargent did not receive formal schooling and was taught at home by his father and mother. He proved to be an excellent pupil excelling in languages and the arts. Art played a great part in his early life as his mother was a talented amateur artist and his father was a talented medical illustrator. Following more additions to the family and because his wife wanted to remain in Europe, John Singer Sargent’s father eventually resigned his post at the Willis Eye Hospital in Philadelphia and acquiesced to his wife’s wishes for the family to remain in Europe.

John Singer Sargent soon developed a love of art and his father had him enrol at the Accademia di Bella Arti in Florence during the winter of 1873/4. In 1876, at the age of eighteen, Sargent passed the entrance exam to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Here he studied anatomy and perspective and spent time in the Paris museums copying the works of art of the masters. In those early days at the art academy Sargent was schooled as a French artist. It was the era of French Impressionism and he was greatly influenced by the work of the Impressionist movement. He was also a lover of the works of art by the Spanish painter, Velazquez and the Dutch master Frans Hals.

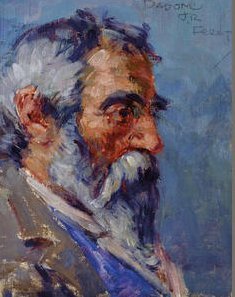

However nearer to home he was inspired by his art tutor, the French painter, Carolus-Duran, a portrait of whom he completed in 1879. John Singer Sargent’s reputation as a great artist and portraitist grew rapidly and in Paris he was the toast of artistic circles. Everything he did was loved by the critics and the public. The Parisians loved him. He could do no wrong. Well actually he could and did and through one painting, a portrait of a lady, his fall from grace was rapid and final and caused him to exile himself from Paris and France and take refuge in England. So what happened? The answer to this question is examined in this very blog.

The lady whose portrait caused such a stir was Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. Virginie Amélie Avegno was born in New Orleans in January 1859. She was the daughter of a white Creole family. Her father was Major Anatole Placide Avengo, a Confederate army soldier and her mother was Marie Virginie de Ternant who came from a wealthy Louisiana plantation owning family. Her father was killed during the American Civil War at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862. Five years later in 1867 her widowed mother took her eight year old daughter to live and be educated in Paris and as a teenager was introduced into high French society.

Virginie Amélie Avegno blossomed into a beautiful woman. She was a pale-skinned brunette. She was renowned for her great beauty and was accepted into Parisian society circles. She dazzled all who met her with her exquisite clothing and undeniable beauty. She mastered the art of make-up to enhance her looks and was known for her heavy use of chalky lavender powder which was dusted on her face and body affording her a very distinctive pallor. Her beauty was unique. She had a long nose which was somewhat longer than the accepted norm, her forehead was also too high and yet these physical characteristics never detracted from her hourglass figure and the seductive way she would walk when entering a room of people.

In his 2011 book The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris, David McCullough quotes an American art student named Edward Simmons who wrote about seeing Virginie and how the sight of her was unforgettable:

“…She walked as Virgil speaks of a goddess—sliding—and seemed to take no steps. Her head and neck undulated like that of a young doe, and something about her gave you the impression of infinite proportion, infinite grace, and infinite balance. Every artist wanted to make her in marble or paint…”

As always beauty as well as bringing out admirers, brings about jealousy and many of her detractors labelled her an arriviste, one who has attained a high position but has not attained general acceptance or respect. I suppose we would liken her to one of the nouveau-riche looked down on by the “old establishment rich”

A mother’s most fervent wish is to see her daughters marry successfully which often translates into having their daughters marry a wealthy man. Virginie’s mother must have been well pleased when her daughter married a wealthy French banker, Pierre Gautreau, and her daughter now had two of the greatest assets of life, beauty and a wealthy husband who held a great status in Parisian society.

John Singer Sargent met Virginie Gautreau at a social gathering around 1881. He was smitten by her beauty and elegance; some say he soon became obsessed with her. Having met her he wanted just one thing from life – to paint her portrait and have it exhibited at the Paris Salon so all could admire “his lady”. Sargent had been inundated with portraiture commissions but on this occasion it was he who approached his desired sitter to ask if she would acquiesce to become the subject of his portrait. Sargent realised that Gautreau was both part of high class Paris society and a renowned beauty and thus a portrait of her by him at the Salon would bring great kudos and he probably realised that if he portrayed her seductively it would cause a sensation similar to Manet’s Olympia at the 1865 Salon. Sargent had unfortunately not realised how sensational it would turn out.

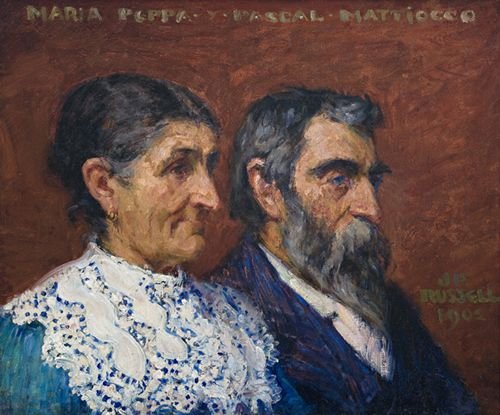

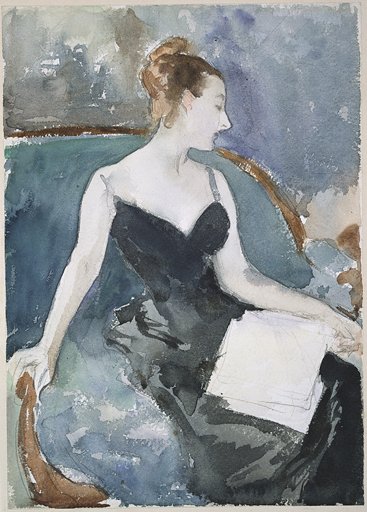

by John Singer Sargent (c.1883)

Harvard Art Museum

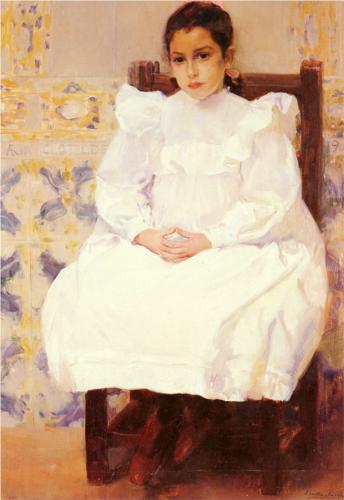

After some help from colleagues Sargent persuaded Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau to sit for him. For months on end he would complete many line drawings of her head in profile. He would complete studies of her in pencil and watercolour, sometimes simply relaxing on a chaise-longue in a low-cut evening dress or depicted her in oil painting sketches drinking a champagne toast. In the summer of 1883, he stayed at the Gautreaus’ country estate in Brittany but admitted to his friend the writer, Vernon Lee, that he was still struggling to do justice to this un-paintable beauty. He was also now having doubts as to whether it would be accepted into the 1884 Salon by the Salon jury.

In the winter of 1883, Sargent moved his Paris residence which had been on the Left Bank to a new studio across the Seine in the fashionable Parc Monceau neighbourhood and it was here that he completed his full-length portrait of Gautreau. It was a nerve-wracking time for Sargent as he had suffered a loss of self-confidence in his artistic ability in respect to the depiction of his beloved beauty. Despite his worries, the painting was finally completed in 1884 and the Salon jury accepted it into the 1884 Salon. This was the sixth year in a row that the Salon had accepted works by Sargent. Before the Salon opened there was already a frenzied excitement about the portrait. Gautreau had talked wildly and incessantly to her friends and acquaintances about the painting, even though she had never seen the finished work.

as exhibited at 1884 Salon

In the painting, Gautreau is seen dressed in a long black satin skirt with its sultry low-cut black velvet bodice. Against the deep black of the dress and the plain dark background, the deathly blue-white of her powdered skin was even more eccentric and noticeable. Her shoulders are bare with the exception of two narrow jewelled straps. Gautreau posture is one in which both her shoulders are held back, her body faces us and yet her head is angled to the left, which fully highlights her stunning profile. Her left arm rests on her hip with her hand gripping the material of her dress. Her right hangs down in a twisted manner s her fingers grasp the top of the table. The result of this distorted pose was to create tension in the neck and arm but it also highlighted the subject’s graceful curves. Her hair is pinned up high on her head atop of which is a tiara. Sargent must have “designed” this un-natural pose presumably because he believed it brought a haughty sensuality to his sitter, for remember, besides wanting to do justice to his sitter’s beauty he also wanted this work to have a sensational affect when it was exhibited. It was probably this thought of sensationalism that made him make the cardinal error which was to damn him. During one of Gautreau’s sittings the thin strap of her dress had slipped from her right shoulder and as she was about to re-adjust it when Sargent told her to leave it down it was and he decided to make the portrait even more sultry by portraying Gautreau’s right shoulder bare. The die was cast and the painting with the strapless shoulder went on exhibition under the title Portrait of Madame *** although most Parisians were aware that it was the portrait of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau.

Even though the Salon had just opened the picture was condemned for what was termed the sitters’ “flagrant insufficiency” of clothing. Little was said about the other aspects of the work, it was all about the seductive pose and dress (or undress) of the sitter. The Paris public could not stop talking about Sargent’s portrait of Gautreau. It was fast becoming a scandal of epic proportions. The painting received many critical reviews. Some objected to the portrait on the grounds that they disliked Madame Gautreau’s décolletage, others criticised what they termed the repulsive colour of her skin. Few however were less harsh and stated that they liked the modern approach to the portrait and congratulated Sargent on is courageous approach. It is difficult to understand the furore over the suggestiveness of the black dress when paintings of nudes littered the walls of the Salon but of course they would normally have biblical or mythological connotations to them which made blatant nudity acceptable. Maybe it was the haughty pose of the arriviste with her heavily powdered features which was too much for the critics and public alike. Gautreau herself was humiliated by the whole affair and her mother, Madame Avegno, who was also horrified with publicity surrounding the portrait, demanded Sargent remove it from the Salon. He defended the portrait, telling the irate mother that it was a truthful likeness of the pose of her daughter and the clothes she wore.

Sargent had scandalised Paris society and he was widely criticised in Paris art circles for being improper. For Sargent the criticism of the work and of him as an artist was almost impossible to bear. He had been living and working in Paris for ten years and during that period he had received nothing but praise for his work and the commissions had poured in on the back of such praise. The criticism of the portrait went beyond a simple poor review. He was being mocked by the Paris public for what he later stated was the best painting he had ever completed. For him the work was a true masterpiece but it would take a long time before the world acknowledged that fact. Sargent hung the work first in his Paris studio and later in his studio in London and from 1905 onwards he allowed it to be seen at various international exhibitions.

with the position of the strap of dress altered

Sargent repainted the fallen strap on Guitreau’s right shoulder, re-titled it Madame X and eventually sold the work to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1916 where it is housed today. An unfinished second version of the same pose is in the Tate Gallery London.

Sargent found the criticism unjustified and shortly after the 1884 Salon, in the May, at the age of 28, he left Paris disillusioned by the incident and disappointed by the fall off of sales of his paintings and moved to London where he remained for the rest of his life England. Although his long-term career as a portraitist in France was over, he once again thrived artistically in the English capital and some say that it was here that he reached the pinnacle of his fame. In those days to have you portrait done by Sargent was looked upon as having it painted by the best portraitist of the time.

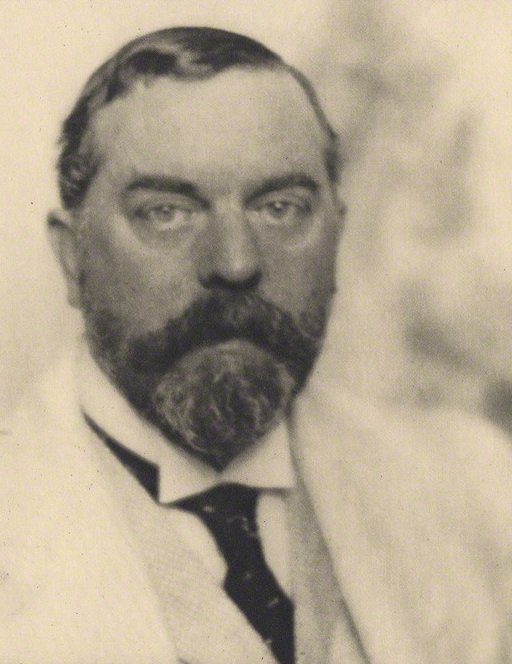

(1856 – 1925)

He died in London in 1925, aged 69.