The term genre painting relates to works depicting scenes of everyday life. Such depictions embrace scenes of ordinary people at work or enjoying their leisure time. This type of painting flourished in Protestant Northern Europe as an independent art form. The first great advocates of genre painting were the Dutch Realist artists of the 17th century, such as Adriaen Brouwer with his riotous pub scenes, Adriaen Van Ostade, who painted genre scenes depicting peasants enjoying their home life or relaxing in an inn.

My favourite has to be Jan Steen, who ran an inn and depicted people in their homes.

In France there were genre paintings by the likes of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin who depicted servants and children. The harsher realities of working life featured in genre paintings of Jean-François Millet, Daumier, Courbet, van Gogh, and Degas whilst joyous life experienced in bars and cafés featured in works by Toulouse-Lautrec.

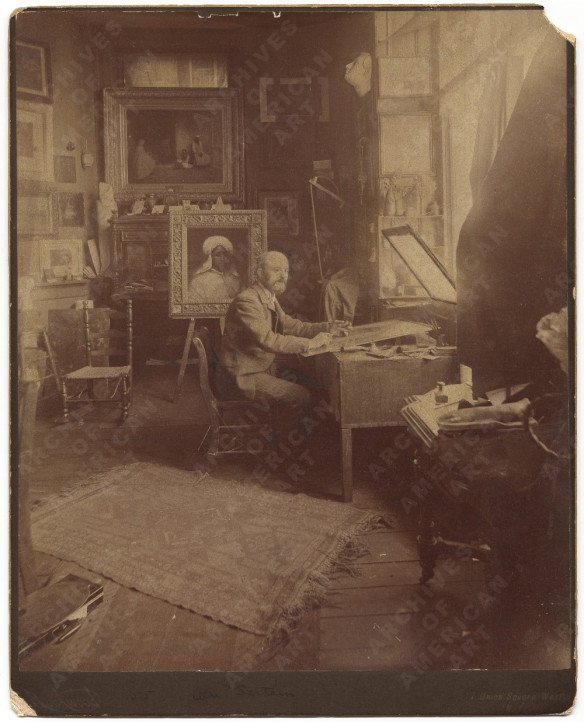

My featured artist today is the English genre painter and portrait painter Charles Spencelayh. Genre paintings, as well as being a pleasure to observe, are an insight into everyday life before the era of cameras and television. The genre and Academic portrait paintings of Spencelayh looked at life during Victorian and Edwardian times and gives us a great insight into life and fashion in those times.

Charles Spencelayh was born in Rochester in Kent on October 27th 1865. He was the youngest of eleven children and was the son of Henry Spencelayh, an engineer and iron and brass founder who sadly died before his son was born. Charles’ first steps into the world of art came when he was given his first set of paints at the age of eight and he soon progressed to copying Old Masters. He studied art at the National Art Training School, South Kensington, which later became known as the Royal College of Art, where he won a prize for his figure drawing.

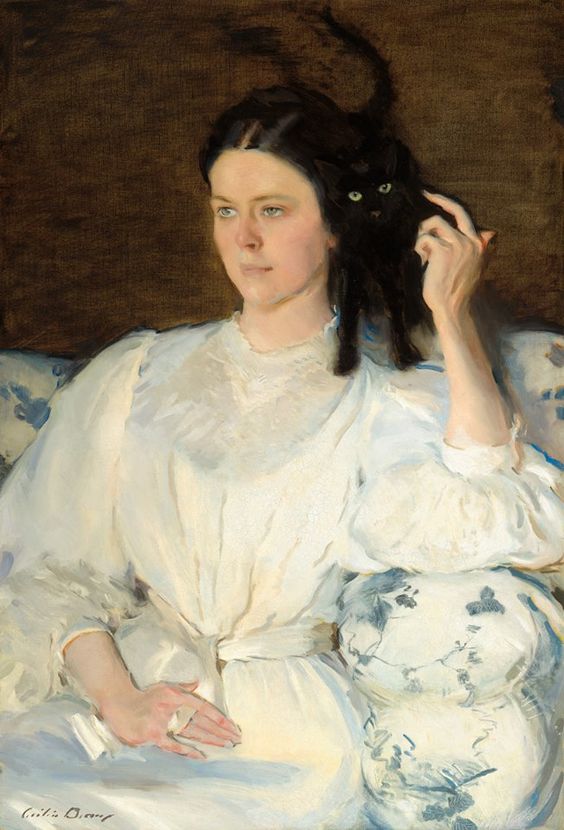

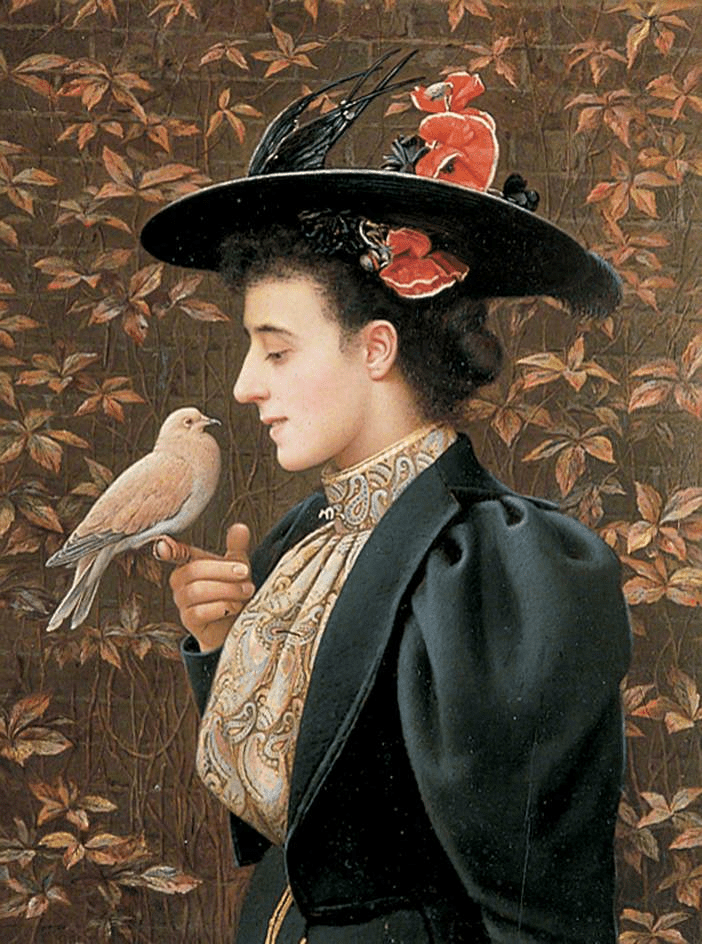

Charles Spencelayh married Elizabeth Hodson Stowe, who worked as a governess, at St. Paul’s, Penge in 1890 and the couple started married life in Chatham. According to the 1891 census Elizabeth’s occupation was given as a tobacconist. She appears in many of her husband’s paintings including My Pet which depicts Elizabeth, in profile, holding a dove.

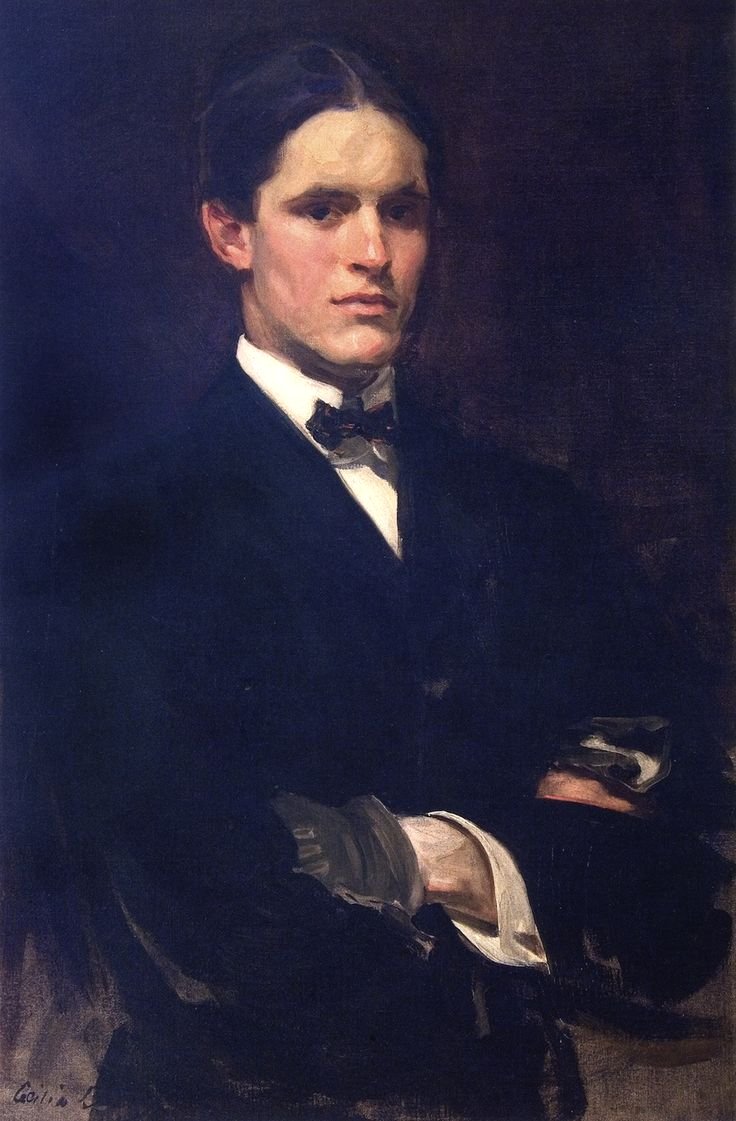

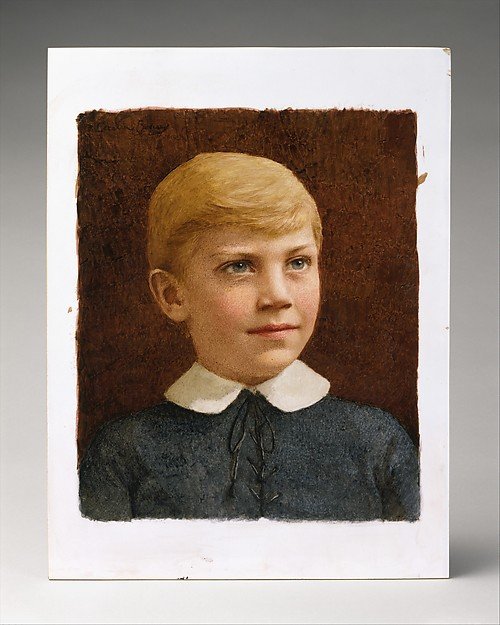

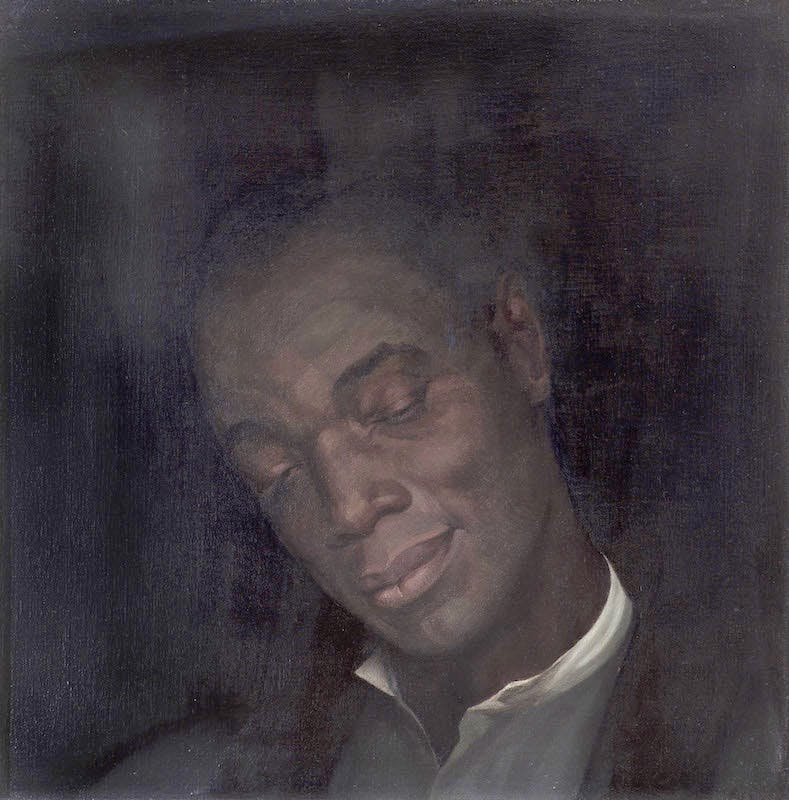

In 1891 the couple had their one and only child, a son, Vernon who went on to become a talented artist and ivory miniaturist, having been taught by his father. Vernon served as an officer in WW1 and was held as a prisoner of war in Germany. He, like his mother, appeared in a number of portraits by his father.

Another fine portrait by Charles of his son, Vernon, in uniform is owned by The National Army Museum. This portrait by his father is a fond record of his son preparing to depart for war. This Academic-style portrait of his son has an intensity and could almost be mistaken as a photograph. Vernon Spencelayh’s regiment was the West Yorkshire Regiment, denoted by the motif of the white horse of Hanover on the cap badge. He was involved in a number of battles on the Western Front and at Gallipoli.

In 1896, Spencelayh became a founder member of the Royal Society of Miniature Painters, Sculptors and Gravers, a Society which was formed with the stated intention:

“…to esteem, protect and practice the traditional 16th Century art of miniature painting emphasising the infinite patience needed for its fine techniques…”

During his lifetime Spencelayh exhibited 129 miniatures at their exhibitions. Probably one of his most famous miniatures was a postage stamp sized portrait of King George V for his wife, Queen Mary’s celebrated Doll’s House, designed by Edwin Lutyens, which was exhibited at the Wembley Exhibition of 1924 and now housed in Windsor Castle. Queen Mary’s and Princess Marie-Louise’s thank you letter was one of Spencelayh’s most treasured possessions. Spencelayh was a favourite of Queen Mary, who was an avid collector of his work and she bought many of his paintings when they were exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibitions and she even commissioned one painting, which Spencelayh titled ‘The Unexpected’ due to his surprise at receiving such a request.

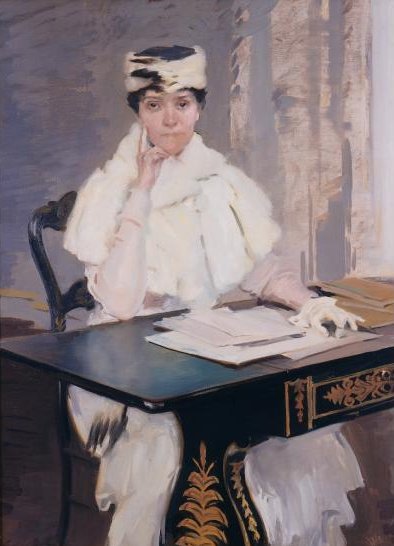

The high-points of Spencelayh’s artistic career were the years between the two World Wars. He had acquired a wealthy patron, Joseph Nissim Levy, a prosperous Manchester cotton merchant and during the 1920’s completed a number of portraits of Levy’s social circle. Mr. Levy’s admiration of the talented artist went so far as to give Spencelayh and his family use of a residence in Manchester. In 1924 Spencelayh painted an intimate portrait of Joseph’s wife titled Rosie Levy taking afternoon tea at the Midland Hotel Manchester. It is a masterpiece in the way Spencelayh has captured the folds of the rich fabric backdrop and the furnishings with their reflective surfaces.

In the early 1930’s the Spencelayh’s moved south to Grove Park and Lee a suburb of south London, but sadly, his wife, Elizabeth died there in 1937 and was buried four miles away in Chislehurst Cemetery.

Spencerlayh had his work exhibited at the Paris Salon, but most of his exhibitions were in Britain. For sixty years until his death in 1958 he exhibited more than 30 paintings at the Royal Academy, with his work entitled Why War winning the 1939 Royal Academy ‘Picture of the Year’. Spencelayh had fought in the First World War and in this painting, he depicts another veteran of that war in his darkened sitting room. He blankly stares into space. He is forlornly envisaging the onset of the Second World War. The artist has added so much detail in this painting that we can build up a picture of how the man lives. We see, on the table next to him, a new gas mask issued to him by Lewisham Council and lying on a chair is a newspaper, emblazoned across the front page is the story covering Chamberlain’s abortive mission to make peace with Hitler. Spencelayh’s talent as both a genre painter and portraitist and his training as a miniaturist allowed him to build up a pictorial story by his depiction of visual clues in painstaking detail.

His 1942 painting It’s War brings home the hardship felt by many during the Second World War. Painted in his studio with a large amount of props which he accumulated during his visits to bric-a-brac shops it depicts the hard times suffered by many during the conflict. It is part portraiture, part genre and part still-life. Its is testament to the genius of the man.

Although the War had ended and the Allies had been victors, Many in England had to suffer years of deprivation. Food was rationed and hardships endured as is beautifully depicted in Spencelayh’s 1946 painting, His Daily Ration in which we see an elderly man staring at his meagre meal.

One theme which appeared in many of Spencelayh’s paintings was of old men pottering around in junk shops or in cluttered rooms in their homes. These were classic Victorian genre works which were pictorial histories of the between-War days in England.

Many of his subjects were of domestic scenes, painted with such definition that they are almost photographic. In his 1935 painting The Laughing Parson, we see the parson dressed in a grey morning suit, resplendent with his “dog collar”. He is half slumped in his wing back armchair as he peruses the latest issue of the satirical Punch magazine. By the look on his face and his broad smile, something in the magazine has amused him. Once again Spencelayh has added numerous items of furniture and accessories which tell us about life in those bygone days.

In 1940, Charles remarried, and his second wife, another Elizabeth and he continued to live in Lee but after a particularly fierce German bombing raid over London, they were rendered homeless. Worse still many of his paintings were destroyed. The couple then moved north to Olney were his wife’s family lived and soon after, setting up home in the Northamptonshire village of Bozeat where they remained for the rest of their lives. It was during those years at Bozeat that Spencerlayh produced some of his best loved paintings often featuring residents of the village who were often treated to a home-cooked meal as payment for modelling for one of his paintings.

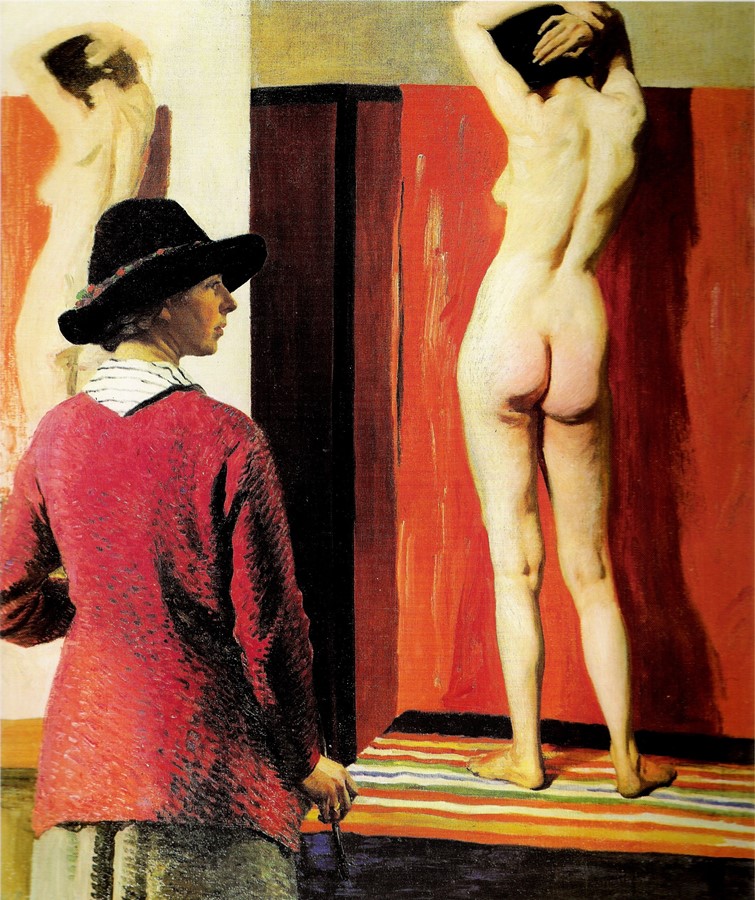

Spencelayh set up his studio with room-sized screens bedecked with patterned wallpaper and had a chest, full of props, with which he would “dress” the room. Charles ‘dressed’ the room using “props” from his collection, such as Toby jugs, stuffed birds, Windsor chairs, clocks and cheap watches as well as patriotic framed pictures of Lord Nelson and members of the Royal Family. Look at the background of his 1947 work A Lover of Dickens. The props he used to add meaning to the painting were arranged haphazardly to give a sense of everyday clutter. Maybe the man lived on his own and a regime of “tidiness” was not forced upon him !

By the late 1950’s his eyesight began to fail but that did not deter him and he continued to paint and in 1958, three of his works were accepted into the Royal Academy Summer, including a poignant work titled The Faded Rose. Sixty-six years earlier he had his first work exhibited, a miniature entitled Mrs Robins and he is considered to be one of the most prolific artists to show at the Royal Academy. Notwithstanding this, he was never made an Associate of the Academy, which baffled many including himself. He wrote to his Canadian agent, George Nuttall in 1956 about this unforgiveable omission. He commented jokingly:

“…I do not know, unless I am not old enough, or work not sufficiently good, which is my aim to yet improve although I cannot wear glasses to paint eventually this will stop my efforts I’m sure of it…”

Charles Spencelayh died, aged 92, in St Andrews Hospital, Northampton on June 25th, 1958 and after a funeral service conducted by his friend and executor the Reverend W.C. Knight in the 12th century church of St Mary the Virgin, Bozeat, he made his final journey back to Kent and was buried with his first wife in Chislehurst Cemetery.

Most of the pictures came from ARC and Art UK and Spencelayh’s biography came from a number of websites of galleries which house some of his paintings and the Chislehurst Society website:

Click to access CharlesSpencelayh.pdf

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.