Part 2. Edward Willis Redfield

The second artist I am looking at who was an early member of the New Hope Artists Colony was Edward Redfield

Edward Willis Redfield

Edward Willis Redfield was born on December 18th 1869 in Bridgeville, Delaware, before moving to Philadelphia as a young child. He was the youngest son of Bradley Redfield, who owned plant nurseries and sold fruit and flowers, and Frances Gale Phillips. He had two older brothers, Eugene and Elma, an older sister Ada and a younger sister May. Even at the age of seven he showed a love and talent for art and aged seven he exhibited a drawing of a cow in a competition for school children at the Centennial Exposition in 1876. From an early age, he studied at the Spring Garden Institute and the Franklin Institute and continued to show artistic talent. It was Redfield’s aim to be accepted into the Pennsylvania Academy, so in preparation for studying there, he received training from a commercial artist, Henry Rolfe. In 1887 Edward’s dream came true when he was accepted on a two-year course at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. At the Academy his tutors were Thomas Anshutz, James Kelly and Thomas Hovenden. Anshutz, like Thomas Eakins, focused on an intense study of the nude as well as on human anatomy. While a student at the Academy Redfield met Robert Henri, who would later become an important American painter and educator and he and Henri became lifelong friends with Henri often spedingt weekends at the Redfield home.

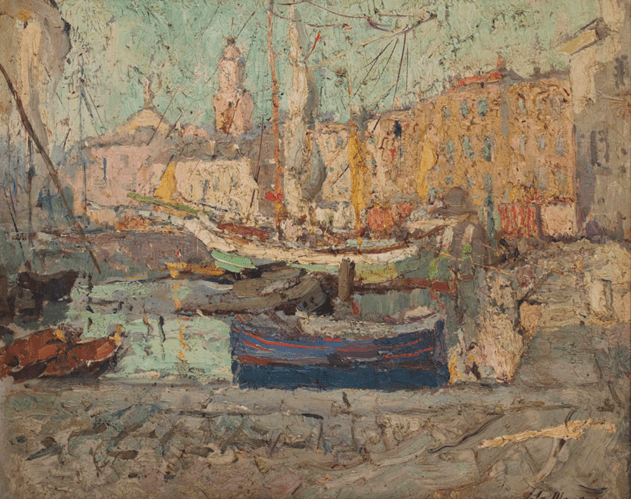

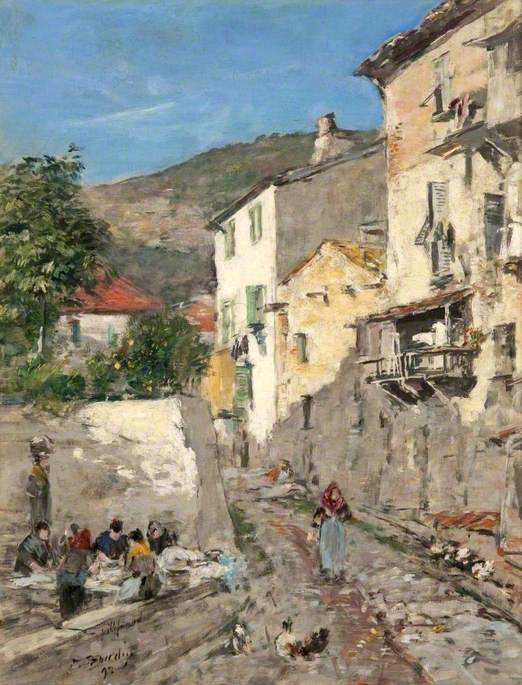

Village of Equihen, France by Edward Willis Redfield (1908)

Once he had completed his studies at the Academy in 1889, he approached his father for financial support for his proposde trip to study art in Paris. Redfield’s father agreed to send his son fifty dollars per month to finance a period of study in Europe and so Redfield left for Paris with the sculptor and former fellow student, Charles Grafly and they met up with Robert Henri in the French capital. Redfield and Henri attended classes at the Julian Academy, a school which provided art tuition to foreigners who had difficulty gaining entrance to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. His instructors there were William Adolphe Bouguereau, one of the leading and best-known French academic painters and Tony Robert-Fleury. .Whilst residing in France Redfield became influenced by the work of the Impressionist painters Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and the Norwegian artist Fritz Thaulow.

Hotel Deligant in Bois-le-Roi-Brolles

It was while he was living in France that Redfield met Elise Devin Deligant, the daughter of the innkeeper of the Hotel Deligant in the village of Bois-le-Roi, a French commune located on the edge of the forest of Fontainebleau and along the Seine, 6km from Fontainebleau and 60km from Paris. The village inn became a meeting place for Redfield, Henri, Grafly, and they attracted other young artists who would come and the enlarged group would have long discussions about art and aesthetics. It was winter at the inn and Redfield became captivated by local snow scenes. Originally Redfield had set his heart on becoming a portrait artist but he abandoned this idea and decided to concentrate on landscape painting. He stated the reason for his decision:

“…With landscape, if I make it good enough, there are many who will appreciate it. Portrait painting must please the subject as a general thing – or no pay! It’s a hired man’s job…”

Canal en Hiver by Edward Willis Redfield

Many of those artists who used to meet at the inn submitted works to the Paris Salon of 1891. Redfield sent his painting entitled Canal en Hiver, one of his first winter snow scenes and it was accepted.

Redfield left France in 1892 to return to America where his one-man exhibition was being staged in Boston. The following year, 1893, Redfield returned to London where he married Elise Deligant. Sadly their first child died and this tragic event caused his wife to suffer from bouts of depression and mental illness, all her life. However, the couple went on to have five children, three sons, Laurent, Horace and George and two daughters, Louise and Frances.

1898 Historical Map of Center Bridge and Hendrick Island. Red arrow marks position of Redfield’s house.

On returning to America Redfield and his wife settled in Glenside, Pennsylvania but in 1898 they relocated to a home he had renovated in the Pennsylvania town of Center Bridge which was situated alongside the Delaware River towpath and several miles north of New Hope. They purchased a property that was situated between the Delaware River and the Delaware Canal in Center Bridge. The property included an island in the river, known then as Hendrick Island, where his father lived and farmed.

Center Bridge by Edward Willis Redfield (1926)

Redfield was one of the first painters to move to the area and is thought to have been a co-founder of the artist colony at New Hope along with William Langson Lathrop, who had taken up residence in New Hope that same year. Soon after settling in Center Bridge, Redfield began to produce a series of local snow scenes and soon his name became synonymous with the painter of the winter landscapes. Redfield completed his painting entitled Center Bridge in 1904 and it depicts a view of Redfield’s home town from a nearby hill. As expected the scene has changed nowadays since woods and new neighborhoods have grown over these hills. This painting is currently at The Art Institute of Chicago.

The Burning of Center Bridge” by Edward Willis Redfield

The large covered bridge across the river seen on the right of the picture no longer exists as it burned down in 1923 and was captured in Redfield’s painting entitled The Burning of Center Bridge.

New Hope by Edward Willis Redfield (1926)

Redfield’s works were, unlike many of his contemporary landscape painters, monumental in size, in contrast to the often-small sentimental works of the earlier nineteenth-century American landscape painters. He was a fast painter, as he had been taught in his early days, and often completed his 50 x 56 inch winter snow scenes, en plein air, in often harsh freezing conditions, in eight hours. Redfield stated:

“…What I wanted to do was to go outdoors and capture the look of a scene, whether it was a brook or a bridge, as it looked on a certain day…”

Redfield described his modus operandi for the plein air painting sessions saying that he would start by walking to his designated site often trudging through slush and snow with his gear weighing fifty pounds and his huge canvas balanced on his head. He said that he would start with almost no under-drawing and finish his painting in a single session using small brushes to cover the entire canvas with thick paint.

The Rock Garden, Monhegan Island, Maine by Edward Willis Redfield (1928)

Beginning in 1902 the Redfield family spent their summers at Booth Bay Harbor, Maine, due to the generosity of Dr. Samuel Woodward, who financed these annual vacations. In June 1903 the Redfields invited Robert Henri and his wife to spend part of their summer with them. During their stay Henri and Redfield sailed around the neighbouring islands constantly searching out suitable subject matter for their paintings. Henri was especially impressed by the beauty of Monhegan Island, an island in the Gulf of Maine. Redfield’s many paintings depicting New Hope landscapes were now supplemented with Maine seascapes. Other works would focus on the flora found on Monhegan Island, Maine. The Rock Garden, Monhegan Island, Maine by Edward Redfield is a study of peace and tranquillity during a warm summer’s afternoon painted in vibrant colours. In this painting Redfield builds up the paint with multiple layers of thick pigment, creating a rich impasto texture. The lively brushstrokes create a dynamic cross-hatching effect and a pattern of colour that brings the scene to life. In the foreground the vividly coloured and rigorously painted flower beds provide a dynamic contrast to the austere New England clapboard houses. A winding path runs diagonally through the scene, providing a sense of spatial recession to a distant shore. The painting sold for USD 750,000 at a 2015 Christies auction. Redfield was awarded the N. Howard Heinz Prize of $500 for The Rock Garden, Monhegan Island, Maine in 1928 at the Grand Central Art Galleries, New York. Redfield, like Henri, fell in love with the beauty of Monhegen Island so much so that he eventually purchased a house at Boothbay harbour and from then on spent nearly every summer vacation around the area.

Fleecydale Road by Edward Willis Redfield

Redfield completed his painting entitled Fleecydale Road in 1930. This road starts in the town of Lumberville on the Delaware River and ends in Carversville. Lumberville was once the home of another covered bridge across the river which was later replaced with a metal bridge that was restricted to pedestrian traffic. It connected walkers to a state park on the New Jersey side. This picture can be seen at the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, PA.

Winter Reflections by Edward Willis Redfield (1935)

Another snow scene by Redfield was his 1935 painting, Winter Reflections. The painting depicts a view of the buildings in New Hope near the railroad station. The buildings backed on to the canal and you are still able to stand at this very spot on the towpath. New Hope’s railroad station is now just a tourist attraction which provides short rides on an old steam train. The painting is part of the collection of the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

The Mill in Winter by Edward Willis Redfield (1921)

Another winter scene painting by Redfield was his The Mill In Winter which he completed in 1921. In the Redfield archive papers it was referred to as the Centreville Mill. Centreville was a small crossroads between New Hope and Doylestown but has since disappeared as such as an officially named location. This painting is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Spring in the Harbour by Edward Willis Redfield (c.1927)

As Redfield’s international reputation increased, many young artists were attracted to New Hope as according to James Alterman in his book, New Hope for American Art, Redfield was a great inspiration and an iconic role model, and his work is among the most widely recognized of the Pennsylvania Impressionists.

Sadly, in later years, Redfield became disappointed with his early work. In 1947, the year his wife died, he burned a large number of his early works which he considered to be sub-standard. In 1953, at the age of 84, he gave up painting altogether. Redfield talked about his decision saying:

“…I was outside one day. My insteps started hurting. It was very windy and I had a hard time keeping my easel up. So I quit. The main reason though, was that I wasn’t good as I had been, and I didn’t want to be putting my name on an “old man’s stuff,” just to keep going…”

Redfield died on October 19, 1965. Today his paintings are in many major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC.

…..to be concluded.

Information for this blog came from numerous sources including:

New Hope Colony Foundation of the Arts

Edward Redfield – Champion of Winter’s Timeless and Seductive Beauty