Having been touring Europe for the last three weeks I have had a rest from my blog. The last part of my journey was a short three-day stay in Paris and it was almost seven years since I had graced this wonderful city. I have visited many art galleries around the world, and my favourites have been the ones that offer something else other than walls of artwork. I do like artwork which is hung on walls of the interiors of beautiful buildings. It is like a 2 for 1 offering beautiful architecture and magnificent paintings.

Baron Haussman’s Paris

Whilst in Paris there was an exhibition of one of France’s great 17th century artists, and one of the greatest exponents of 17th century Baroque painting, Georges le Tour. However, first let’s have a look at the impressive building which was hosting the exhibition. The Musée Jacquemart-André is a private museum located at 158 Boulevard Haussmann in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. The street named after Georges-Eugène “Baron” Haussmann, a French administrator, who in the mid nineteenth century, with the backing of Emperor Napoleon III, was responsible for the transformation of the ancient impoverished and unhealthy areas of Paris which involved the demolition of 19,730 historic buildings and the construction of 34,000 new ones. Old narrow streets gave way to long, wide avenues characterised by rows of regularly aligned and generously proportioned neo-classical apartment blocks faced in creamy stone.

One such building was Musée Jacquemart-André, situated on Haussman Boulevard, which was the private home of Édouard André and his wife Nélie Jacquemart which was to display the art they collected during their lives. It was what the French term it as a hôtel particulier, a grand urban mansion. Edouard André bought land on the newly created Boulevard Haussmann with the intention of having a mansion built. Building started in 1869 by the architect Henri Parent and completed in 1875.

Portrait of Édouard André by by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

Nélie Jacquemart and Édouard André were an improbable and mismatched couple. She was a Catholic woman and a famous society portrait painter, and he was the Protestant heir to a banking fortune.

Nélie Jacquemart – Self portrait

They married in 1881. Nélie had painted Édouard André’s portrait ten years earlier. Each year, the couple would travel to Italy, buying works of art and slowly amassing one of the finest collections of Italian art in France. When Édouard André died in 1894, Nélie Jacquemart carried on the renovation of their home. She also made many trips to Japan and neighbouring far-east countries adding many Oriental works to the collection. Following her husband’s dying wishes, on her death in 1912, she bequeathed the mansion and its collections to the Institut de France as a museum, and it opened to the public in 1913. The couple’s relationship led to one of the most notable private art collections of fin-de-siècle Paris.

The Tapestry Room

The Round Room

Once inside the Musée Jacquemart-André we are able to glimpse into the splendour of Parisian aristocratic life as it was in the 19th century. We can witness the luxurious setting, both inside and outside of Édouard André and Nélie Jacquemart former mansion. Adorned with the finest works of art, one can see in every room the evidence of their passion for Italian and French art. This was a building which hosted extravagant receptions and soirees.

The Winter Garden and Staircase

Their collection of Italian artwork which Nélie meticulously curated is legendary and includes paintings by Sandro Botticelli, Giovanni Bellini, and Andrea Mantegna. Besides these Italian works of art, the museum houses an remarkable array of French, Dutch, Flemish, and English paintings, as well as sculptures, antique furniture, and objets d’art. Wandering through rooms one observes how they have been preserved in their original state, and one feels that we have been immersed into the world of Parisian high society.

One of the State Rooms and Picture Gallery

The grand salons were designed for hosting lavish events and feature stunning frescoes, sculptures, grand sweeping staircases, and luxurious decor. The experience of walking through lavishly decorated rooms and halls allows us to see how the affluent lived in a bygone era of luxury.

Once the excellent tour of the rooms and garden of the mansion was complete, I went to see the Georges la Tour exhibition which was spread across several upstairs rooms. It was entitled From Shadow to Light which alludes to the way La Tour explored in his paintings nocturnal scenes, half hidden candles, light filtering through a translucent page, glimmers on a skull or a lantern punctuating the darkness in which meditation unfolds.

The Hurdy=Gurdy Man with a Dog by Georges de la Tour (1625)

Georges de la Tour was baptized in March 1593 in Vic-sur-Seille in Lorraine. He was the second of seven children, born into a family of bakers. Following a fire started by French troops during the Thirty Years’ War, his home, his studio, and some of his works were destroyed and he and some of his family escaped to Nancy. A year later la Tour was appointed “First Painter to the King” by Louis XIII and as such, he lived in the Louvre and was officially recognized by the court and the Parisian artistic community. At the height of his career, he painted for many prestigious patrons such as Cardinal Richelieu and the Dukes of Lorraine and became one of the wealthiest painters of his time.

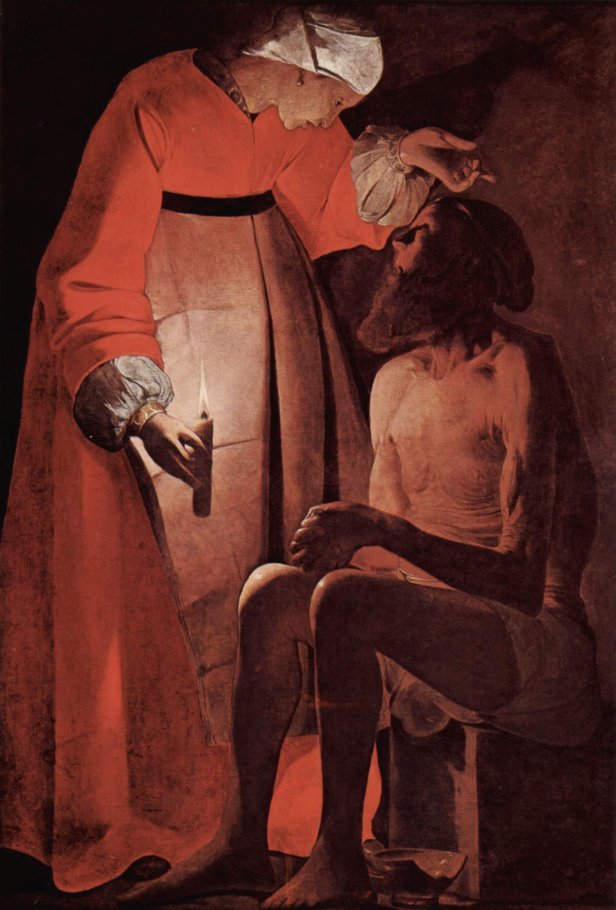

Job Mocked by his Wife by Georges de la Tour (1635)

As can be seen in his paintings, Georges de La Tour was influenced by the Italian painter Caravaggio whose style was then spreading throughout Europe. It is not thought that de la Tour ever travelled to Italy but he was probably influenced by Dutch and Lorraine Caravaggism. De la Tour developed a personal and daring interpretation of chiaroscuro that made him truly original. His paintings are notable for their realism and sober compositions, which contrast with the dramatic intensity of Italian Caravaggist works. Although de la Tour’s work used the technique of chiaroscuro his style is of painting is often alluded to as tenebrism. Tenebrism, which comes from the Italian word tenebroso meaning dark, gloomy, mysterious and is a style of painting using especially pronounced chiaroscuro, where there are violent contrasts of light and dark, and where darkness becomes a dominating feature of the image. This technique was developed to add drama to an image through a spotlight effect and is common in Baroque paintings. Tenebrism is used only to obtain a dramatic impact while chiaroscuro is a broader term, also covering the use of less extreme contrasts of light to enhance the illusion of three-dimensionality.

St Peter Repentent by Georges de la Tour (1645)

The pamphlet that went with the exhibition describes the painting of St Peter as:

“…The celebrated St Peter Repentent exemplifies this sober style, in which lightbecomes the principal sign of the divine. The visual rhyme between the saint’s tonsureand the rooster’s crest introduces a discreet irony, a singular perspective on religious iconography…”

The painting is based on the Bible story of Jesus’s arrest on the night of the Last Supper, when the apostle Peter denied knowing him. Although Christ forgave his betrayal, Peter was consumed by guilt. In his painting, La Tour represents Peter as an old man, reflecting on his past actions in a state of perpetual repentance. The apostle’s red-rimmed eyes and the uncertain light of the lantern evoke the feeling that the Peter has spent anxious sleepless nights and the use of muted colours and simple forms give visual expression to Peter’s solemn and dejected emotions.

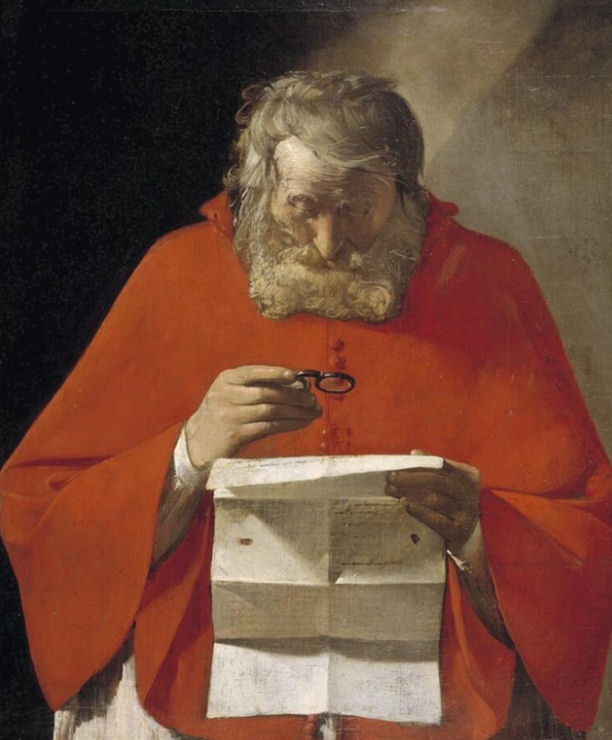

St Gerome Reading a Letter by Georges de la Tour (1629)

The painting by Georges de la Tour’s Saint Jerome Reading a Letter was completed around 1629 and is a masterclass in how to make a single, ordinary action, in this case, reading, carry the weight of a whole life. St Jerome was an early Christian priest, confessor, theologian, translator and historian and his image fills the frame at half-length, wrapped in a cardinal-red mantle. His head bends slightly forward, and a wisped halo of grey hair catches the light that slants in from the upper right in a wedge-like form. In his left hand, Jerome holds a creased sheet of paper and in his right hand, he lifts a small pair of spectacles toward the page, trying to focus on the written words.

St Jerome Reading by Georges de la Tour (1650)

Georges de La Tour is best known for his religious paintings, which are instilled with extraordinary spiritual intensity despite the look of simplicity. In complete contrast to the religious works, de la Tour was interested in scenes of games of cards and dice as well as genre scenes. His interest in depicting card players and card cheats can be seen in two versions he made two years apart.

The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs by Georges de la Tour ( 1630–1634)

The earlier version is one of two versions of the composition by de la Tour and is known as The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs. There are a number of variations in details of colour, clothing, and accessories between the two paintings. This one is now hanging in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.

The Card Sharp with the Ace of Diamonds by Georges de la Tour (1636-38)

The work, the later variation, depicts a card game in which the wealthy young man on the right is being cheated of his money by the other players, who both appear to be part of the scheme. The card sharp on the left is in the process of retrieving the ace of diamonds from behind his back.

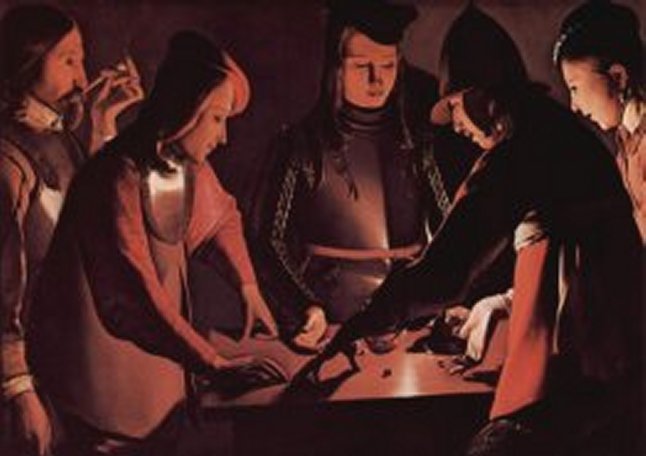

The Dice Players by Georges de la Tour (1651)

De la Tour’s painting entitled The Dice Players is a genre painting which he completed in 1651. In the work he depicts a group of five figures who are deeply absorbed in their game with dice. Their intimate gathering around a table, illuminated by a single, subtle light source, is a good example of his tenebrism-style that emphasizes dramatic contrasts between light and dark. Look how each figure has a different facial expression as we see them all concentrating on the game. Besides this, look at how the artist has depicted details of their period clothes and he has created, through the dim, atmospheric lighting, a vivid record of 17th-century life, and a sense of realism to the scene. De la Tour has used a sombre palette and the careful attention to textural details highlights the gravity of the moment.

Payment of Taxes by Georges de la Tour (1620)

The painting entitled Payment of Taxes by Georges de La Tour was completed around 1620. Once again it highlights la Tour’s love of the artistic movement known as Tenebrism which is characterized by dramatic illumination and stark contrasts between light and dark. It is a large painting measuring 152 by 99 centimetres. The painting depicts a group of figures huddled together around a table. The depiction is dramatically lit by a single, stark light source, casting deep shadows and creating a profound sense of volume and space. This light appears to emanate from a candle or lantern which is out of view, highlighted by the reflective surfaces and illuminating select portions of the figures and objects. The men gathered around the table are engaged in an exchange, with a distinct focus on the act of counting or possibly exchanging money. The artist has focused their expressions and their hands and that emphasizes the gravity and concentration of the transaction at hand. The use of light and shadow not only gives the scene an emotional feeling but it also guides the viewer’s gaze through the composition, emphasizing the movement of money encapsulated in this painting.

Peasant Couple Eating by Georges de la Tour (c.1620)

Georges de la Tour’s painting entitled Peasant Couple Eating was completed around 1623, at the early part of his artistic career. The two half-length figures which are almost life-size are tightly framed in the pictorial space. They face us as if we have interrupted them during their meagre meal of dried peas. The man exhibits a sour and resentful look as he looks down. The woman stares fixedly at us with her deep-set almost dead eyes as she raises a spoon to her mouth. As the background is a simple grey, we have no idea where the event is taking place. However, this background enhances the old couple. The painting of half-length figures like this one was a characteristic of Caravaggio’s style, an artist who influenced de la Tour in his early works. This painting proved very popular and there are records of three 17th century copies.

In the book, Georges de la Tour of Lorraine, 1593-1652, by Furness, the author wrote of the artist:

“……Georges de la Tour is classed as a realist. Realist he is in that his subjects, predominantly if not exclusively religious, are represented in terms of “real” life, often the life of his own country-town and surroundings in Lorraine. But he avoided naturalism; rather, he chose to simplify, modelling his forms by marked contrasts of light and shade, and using large volumes and severe lines, with great selective economy of detail…”

Some of the paintings shown in this blog were not at the exhibition but I wanted to show you more of la Tour’s work.

Did I enjoy the exhibition ? The painting were excellent. However, for me the downside was two-fold. Firstly the rooms displaying the paintings were overcrowded (and this was a timed-enterance exhibition). Some people were moving clockwise whilst others moved anticlockwise and it felt slightly claustrophobic. Secondly all the paintings were accompanied by a card describing the work but they were all in French, rather bilingually. My love of visiting art museums is to buy a book with regards the exhibition and in this case a book about the actual museum itself and the works of the artist were on sale in many languages but none in English.. Brexit ???

I recommend you to the gallery website: