My Daily Art Display today has the slight whiff of scandal about it, or to be more precise, about the sitter for the painting. It is a tale of two paintings, a disgruntled sitter and a furious artist. The title of today’s featured works are Mademoiselle Lange as Danaë and Mademoiselle Lange as Venus and the artist who painted both these rather erotic works in 1799 was the French painter and illustrator, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trisson but more commonly known as Anne-Louis Girodet. Here was an artist whose works straddled the rationalism of Neoclassicism and the flights of fantasy associated with Romanticism.

Girodet was born in Montargis, a small town some 100 kilometres south of Paris in 1767. He had an unhappy start to life with both his parents dying when he was young and he then came under the guardianship of Doctor Trioson who took care of his well-being and education. Later Girodet would add the surname of his guardian to his own in recognition to everything the doctor had done for him when he was young. There is a train of thought that the good doctor was actually Girodet’s natural father. Initially Girodet studied to become an architect and had a desire to follow a military career but finally he decided that the life of an artist was for him.

He studied with Jacques-Louis David and in 1789 was awarded the Prix de Rome by the Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and with that came the scholarship to travel to Italy and stay at the Academy of France in Rome. Girodet remained in Rome for five years.

He returned to Paris in 1793 and concentrated on portraiture and was well known for his glorifying portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte. One of his best known and most controversial portraits is one of the painting I am featuring today. He also spent a lot of time doing illustrations for books. In 1815 his erstwhile guardian Doctor Trioson died and Girodet inherited a fortune and for the rest of his life he spent little time painting and concentrated on writing poetry. Girodet died in Paris in 1824, aged 57.

So that was a little bit about the artist and now to delve into the much more colourful life of the sitter of this painting, Anne Françoise Elisabeth Lange. She was born in Genoa in 1772. Her mother and father were both musicians who with their company of players, travelled throughout Europe performing in musical shows. The young Anne Françoise soon became a young child performer. At the age of sixteen she made her first performance at the famous Comédie-Francais as a pensionnaire, and five years later she was promoted to the position of a sociétaire. It is an interesting theatrical hierarchy. A pensionnaire is promoted to a societaire by a decree of the Ministry of Culture, from names put forward by the general administrator of the Comédie-Française. Once one has achieved the rank of a sociétaire, an actor automatically becomes a member of the Société des Comédiens-Français and receives a share of the profits plus they also receive a number of shares in the Société to which he or she is contractually linked.

Triumph followed triumph in her rolls and soon she became a notable performer in Paris. The turning point came in 1793 when she appeared in a play which had Royalist connotations and as Paris was in the clutch of the Revolution anything alluding to royalty or the monarchy was taboo and the theatre was shut down and the play’s author and the actors were arrested. She spent two periods incarceration and narrowly escaped the guillotine thanks to having friends in “high places”.

Elisabeth Lange bore a daughter, Anne-Elisabeth Palmayre to her wealthy lover, Hoppé, a wealthy banker from Hamburg and two years later bore a son to another lover, Michel-Jean Simons, a Belgian supplier to the French army, whom she later married, after which her acting career virtually came to an end. Disaster struck Simms’ business and he was ruined almost leaving the family destitute. Michel-Jean Simons died at the family’s Swiss home in 1810 and his wife Elisabeth Lange died six years later in Florence.

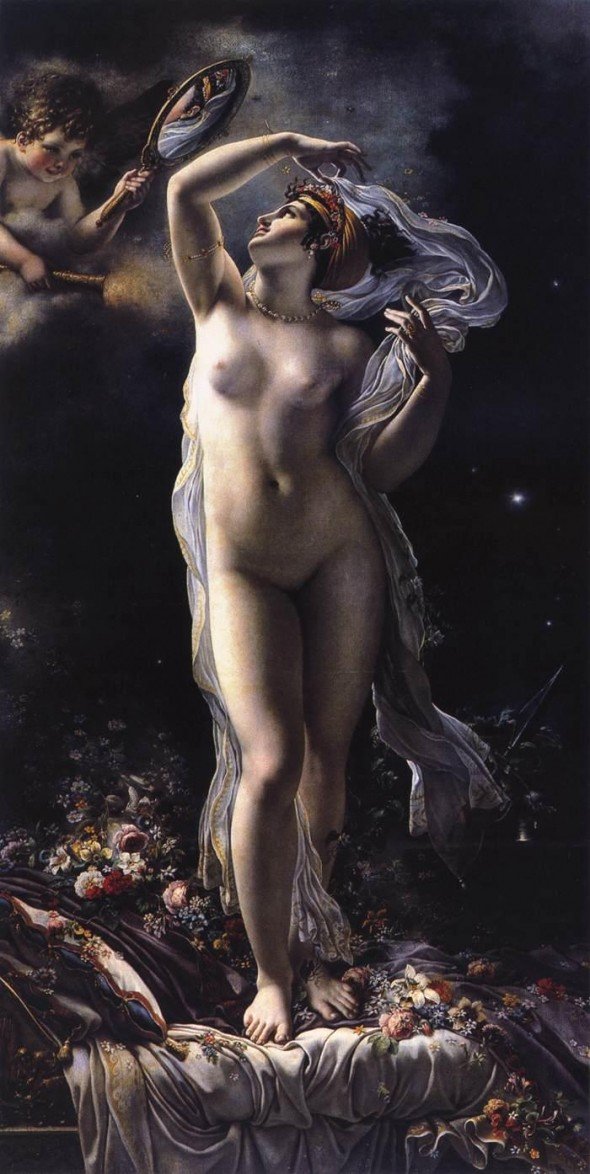

Miss Lange was both very talented and extremely beautiful. She had approached the artist, Girodet, to paint her portrait. He duly obliged and depicted her as Venus, in which she held the pose seen in depictions of the Birth of Venus but in this painting it is Cupid who holds the mirror up to Venus for her to study her reflection. He exhibited the painting at the 1798 Salon exhibition but the sitter was horrified by her depiction and demanded that Girodet should remove it from the exhibition and from public view. Furthermore she refused to pay Girodet the agreed amount for the painting. The artist was furious and in an act of revenge took the painting out of the exhibition, removed it from its frame and ripped it up. He then sent the pieces to Mademoiselle Lange. However his revenge was not complete as he decided to paint another portrait of Elisabeth Lange but this time showing her in a very unfavourable light. He rushed off a satirical painting of Mademoiselle Lange as Danaë in just a few days. Eighteenth-century artists sometimes portrayed people as mythological characters to highlight their virtues but this time Girodet wanted to highlight Mademoiselle Lange’s vices. Danaë was one of the mortals loved by the Greek god Zeus, who transformed himself into a shower of gold and fell upon her. Girodet shows Miss Lange as a prostitute greedily catching and gathering the gold coins in a sheet. In the painting Girodet has featured a turkey with peacock feathers wearing a wedding ring, symbolizing her final lover and husband Michel-Jean Simons whom she married for his fortune, and to the bottom right we have a bizarre mask with the features of another of her lovers, Lord Lieuthraud, with a gold piece stuck in one of its eye sockets. Look at the mirror she holds. It is cracked and this symbolises her inability to see herself as she is, or how Girodet saw her – vain, adulterous and avaricious.

This painting is now at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.