This is the second part of my blog which focuses on lesser-known artists that had a connection with the English county of Suffolk.

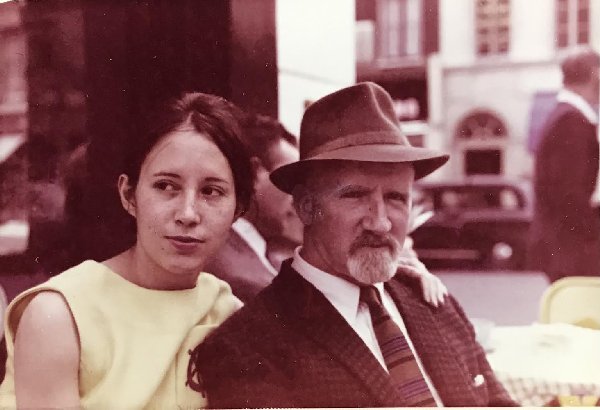

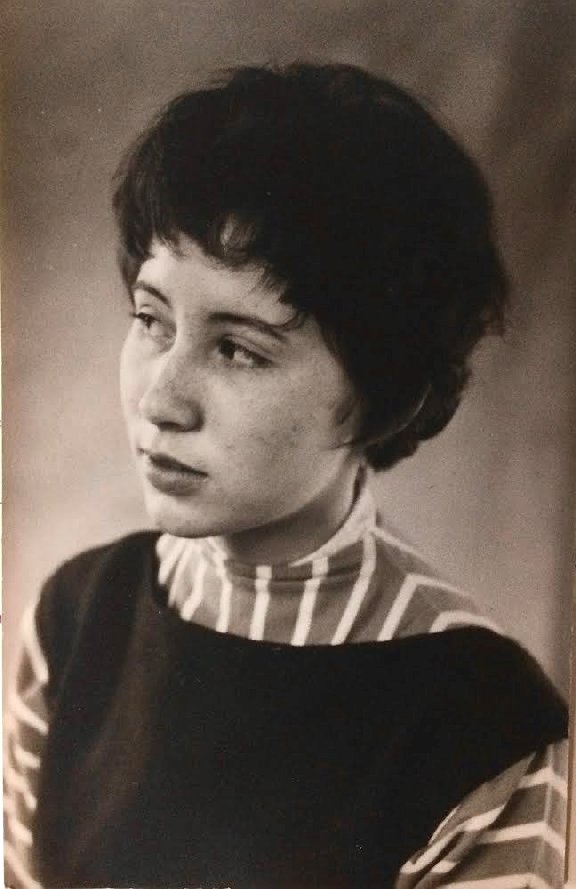

Rose Mead

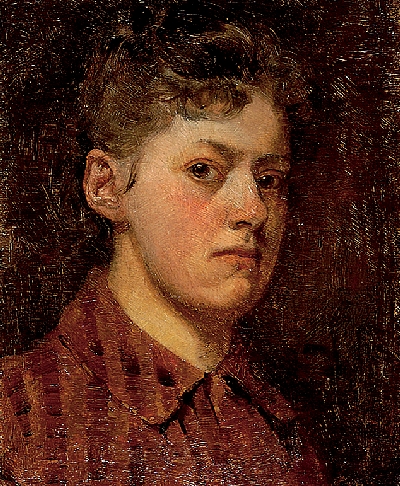

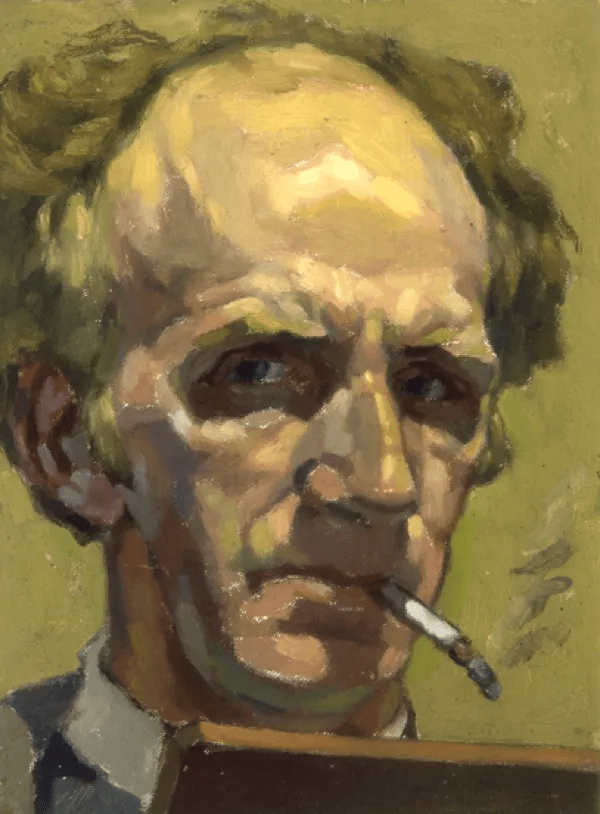

Rose Mead’s self portrait (c.1900)

Emma Rose Mead, known as Rose Mead, was born at 15 Hatter Street, Bury St Edmund’s, Suffolk on December 4th 1867. She was the youngest of eight children, having six brothers and two sisters of Samuel Mead, a master house plumber, glazier and decorator who employed several men, and his wife Emma Mead, née Smith, who married at St James’s Church, Bury St Edmund’s July 1846.

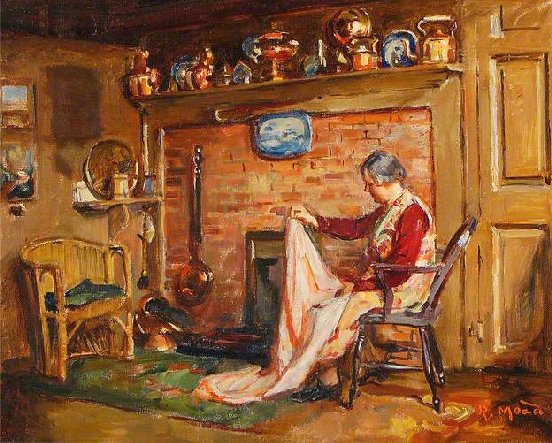

Barbara Stone in the Kitchen by Rose Mead (c.1930). One of Rose Mead’s her best known pictures, was of Barbara Stone who was Rose’s home help

Rose attended the local school for girls. studied at Bury St Edmunds Science and Art Classes from where in 1884, she passed her art examinations and the next year she transferred to the Lincoln School of Art and soon began to exhibit at the Bury St Edmunds and West Suffolk Fine Art Society. Later she went to live with her older brother, Arthur, a bank clerk, in Leatherhead, Surrey and attended the Westminster School in London. Her stay at the college was short-lived as she was called back home to care for her dying father. After his death in May 1895, she spent a year in Paris with her friend Helen Margaret Spanton, an artist and suffragette. Whilst living in the French capital Rose continued her art studies at the Académie Delécluse where she became great friends with another English artist, Beatrice How. During her stay in Paris, she had one of her pastel portraits exhibited at the Paris Salon and it was again exhibited at the Royal Academy the following year.

Interior of the Athnaeum Kitchen by Rose Mead (1933)

Rose returned to London in 1896 but this stay was interrupted once again in 1897 when her mother fell in and she was summoned to Bury St Edmunds to her mother’s Crown Street home to look after her. This was to be her permanent place of residence. Her mother died in 1919. In her later years she lived at St Edmund’s Hotel on Angel Hill and, one day, when she failed to return to the hotel, on investigation Rose was found in the hallway of her Crown Street studio from a fall downstairs and she died from a fractured skull on 28 March 1946, aged 78. Rose never married.

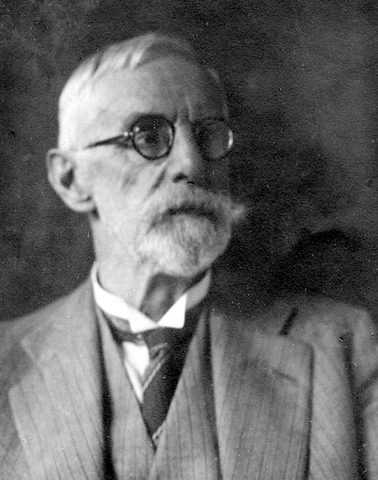

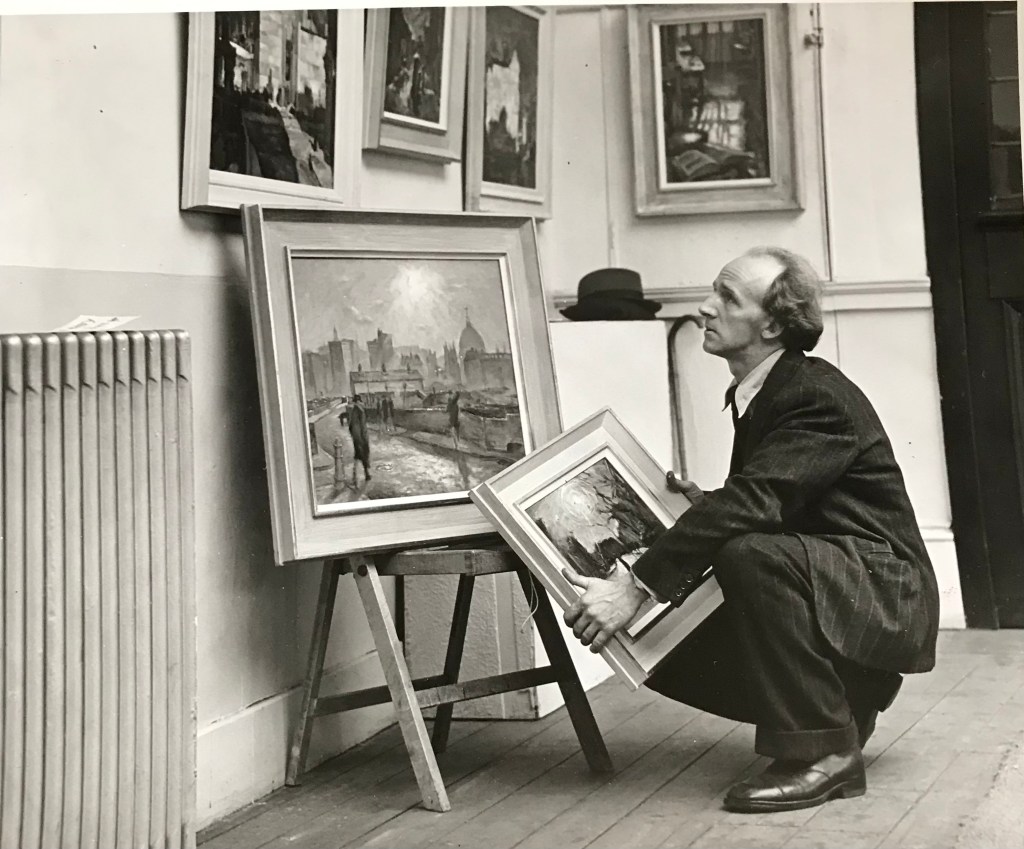

Edwin Thomas Johns

The second artist I am featuring in this blog is Edwin Thomas Johns who was born in the Suffolk port town of Ipswich on December 26th 1882. Edwin was the youngest of five children of William Johns and his wife Isabella Elvira Johns née Wardle. Edwin had four older siblings, three sisters and one brother, Elvira Isabella, Lavinia, Ellen and William. Edwin’s art tuition began when he attended the Ipswich School of Art.

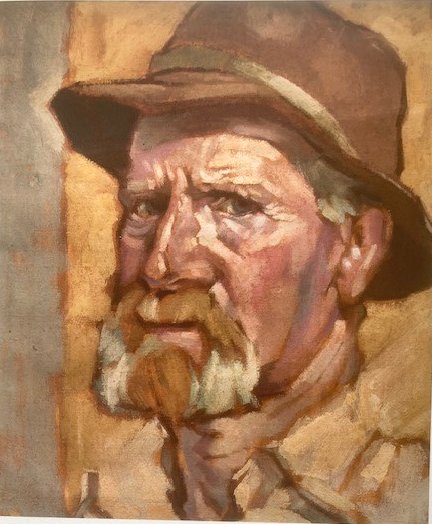

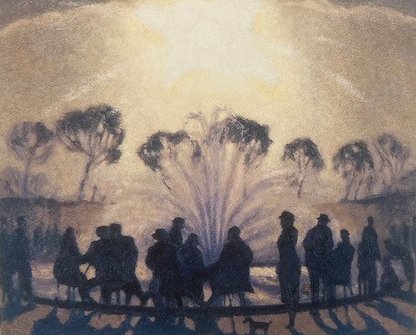

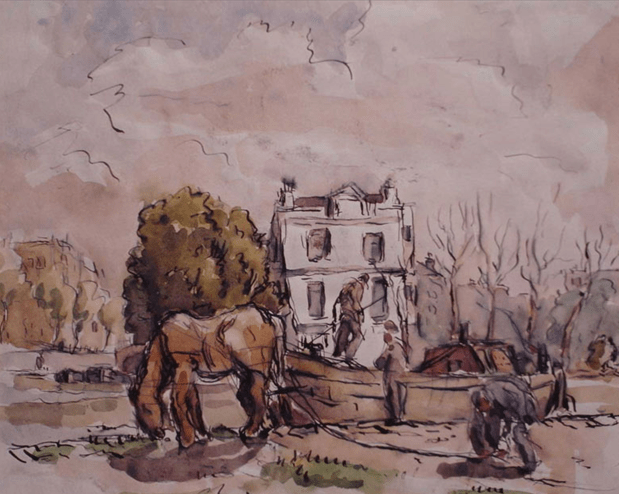

Memories by Edwin Thomas Johns (1929)

Edwin attended the Ipswich School of Art under the headmaster, William Thompson Griffiths. In 1877 Edwin was articled to James Butterworth, a company of architects on Museum Street, Ipswich. When Butterworth retired Edwin completed his articles with William Cotman Eade and later became his assistant. Then the company was renamed Eade & Johns until 1912, when Eade retired and Edwin Johns carried on his own company based in Lower Brook Street, Ipswich. He was a founder of the Suffolk Association of Architects and became its first President. In 1921, his nephew Martin Johns Slater joined the business, which subsequently operated under the name Johns & Slater until Edwin retired in 1933.

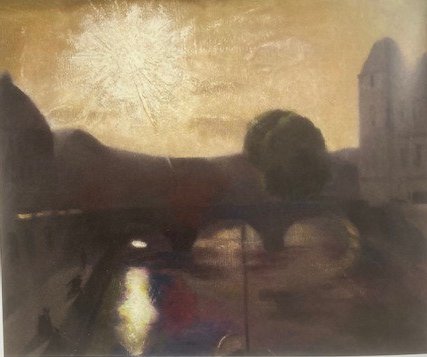

Portrait of a Lady by Edwin Thomas Johns

Edwin Johns was also an accomplished watercolour artist and painting became his main interest later in his life. He was a life member and regular annual exhibitor at the Ipswich Fine Art Club which he first joined in 1887 and remained a member until his death in 1947. At one time he held the office of Club secretary and Club president. He also exhibited at the Royal Academy with several of the works also being shown at Ipswich.

Portrait of a lady with cropped hair, in red dress by Edwin Thomas Johns (1938)

He married at the Congregational Chapel, Redhill on March 29th 1893 His bride was Janet Eliza Prentice. The couple had no children. Edwin Thomas Johns died at his home in Ipswich on November 11th 1947, aged 84.

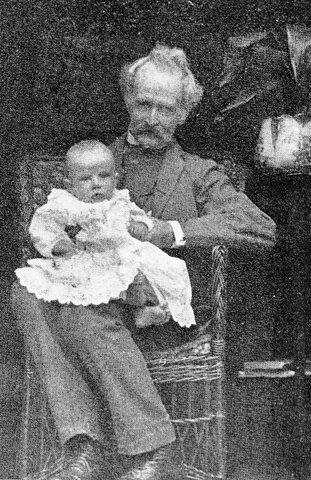

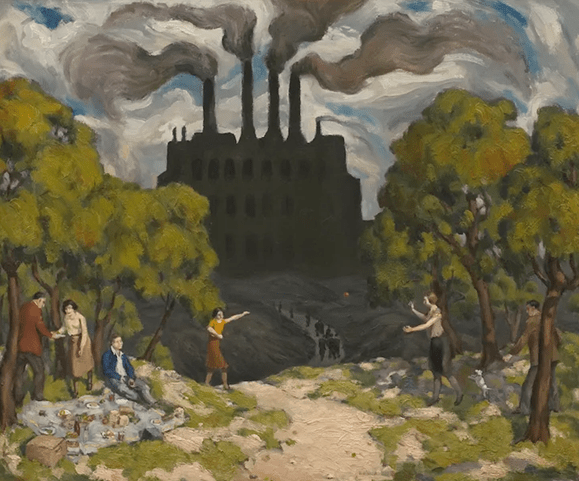

Thomas Smythe

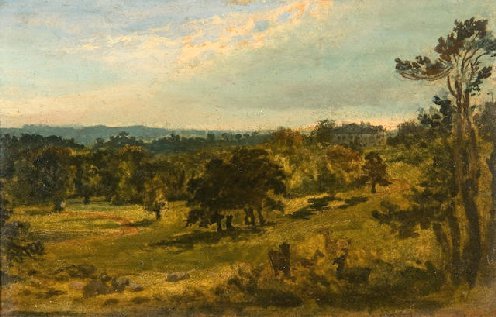

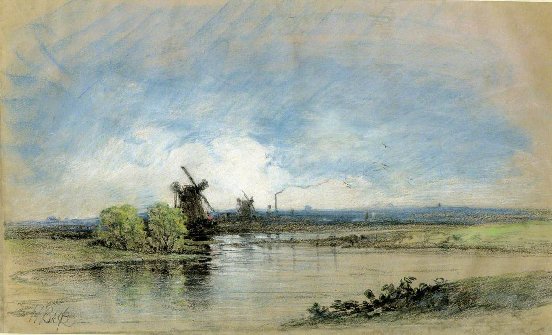

Thomas Smythe was born on November 14th 1825 to James Smyth, a banker, and his wife Sarah Harriet Smythe (née Skitter}. Thomas was fifteen years younger than his brother, the artist Edward Robert Smythe, whom I wrote about in Part 1. It is thought that Thomas went to school run by Charles and Elizabeth Watson at Berners Street, Ipswich.

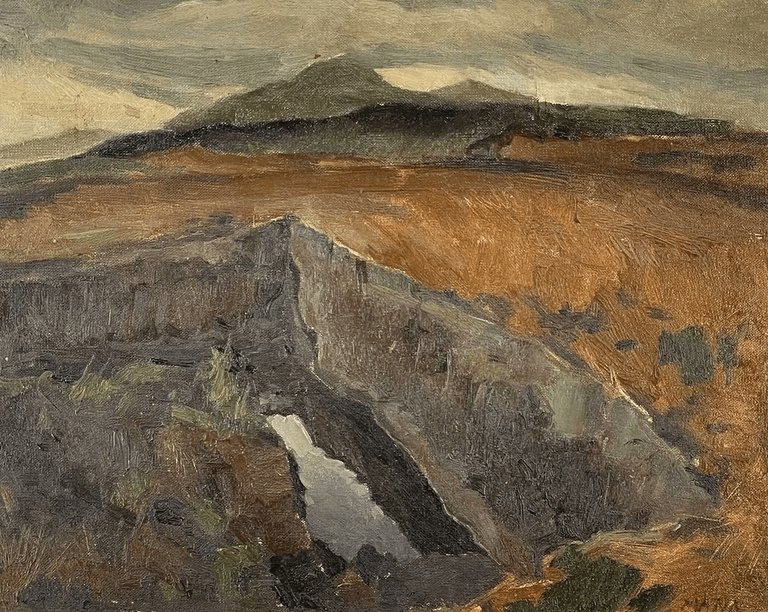

Figures in Winter Landscape with Windmill beyond by Thomas Smythe

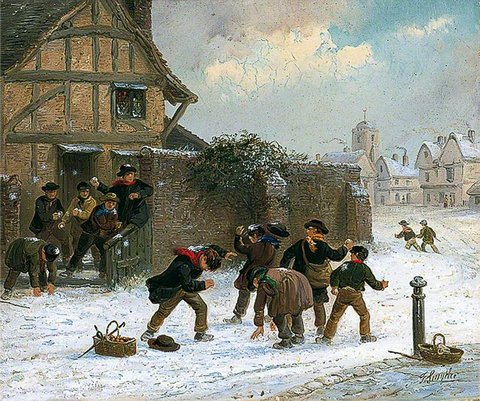

Children Snowballing by Thomas Smythe (c.1900)

Thomas worked alongside his brother from around 1846, until 1851 when Edward Robert Smythe left for the Lancaashire town of Bury. It was then that Thomas set up on his own as a landscape and animal painter in Brook Street, Ipswich. In 1850, Thomas married twenty-one-year-old Miss Pearse from Ipswich. They went on to have five children, Thomas the eldest child became an artist but sadly died in a cycling accident when he was nineteen. Ernest their second son was also an artist and became a book illustrator in London until he emigrated to America. Their son Robert emigrated to Canada.

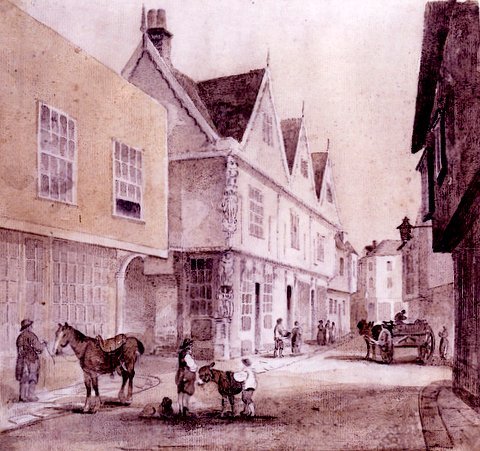

Angel Corner, Fore Street by Thomas Smythe (c.1850)

Thomas Smythe exhibited several oil paintings at the Suffolk Fine Arts Association exhibition in August 1850 which was held at the New Lecture Hall at the Ipswich Mechanics’ Institute. Around 1899 Thomas Smythe went to live, with his son Ernest, in London but died after a short illness, at the home of his son-in-law Frank Brown, at Heathfield, Ipswich on May 15th 1906, aged 81. His wife Jane died at Ipswich in 1919, aged 76

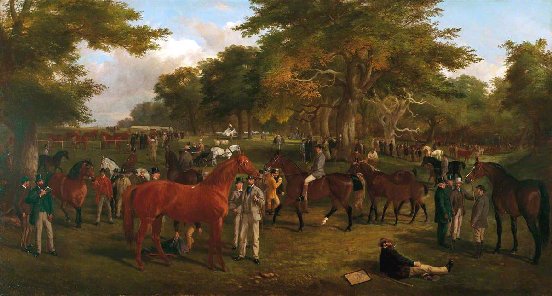

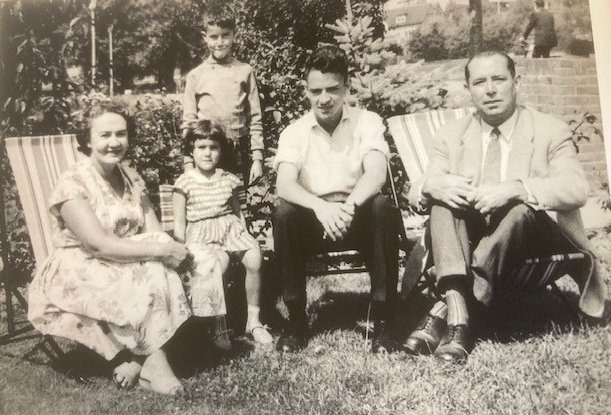

Frederick George Cotman

A more well-known Suffolk artist was Frederick George Cotman. Frederick George Cotman was born at 186 Wykes Bishop Street, Ipswich on August 14th 1850. He was the youngest child of Henry Edmund Cotman, a former silk mercer of Norwich, and his wife Maria Taylor who married at St Andrew’s Church, Norwich in January 1842. Henry Cotman was a younger brother of Norwich School’s more famous artist John Sell Cotman. Frederick Cotman had two brothers, Henry Edmund and Thomas William and a sister Marguerite.

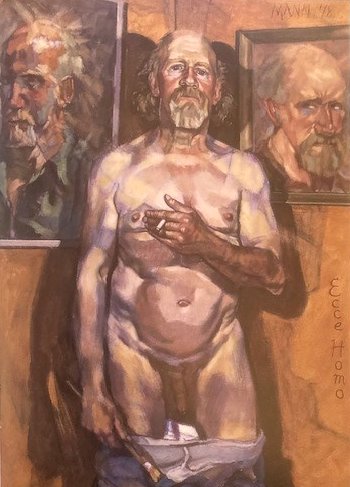

The Death of Eucles by Frederick Cotman (1873)

In 1866, aged sixteen, Frederick attended the Ipswich School of Art and his first work was exhibited in 1867 at the Eastern Counties Working Classes Industrial Exhibition at Norwich, where he won a prize medal. In 1868, he enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy Schools and his ability as a draughtsman and painter in oils and watercolours, was rewarded with four silver and in 1873 a gold medal for his painting, The Death of Eucles, which can now be seen displayed at the Ipswich Town Hall.

The Daphnephoria, by Frederick Leighton (c.1874-76)

At the RA Schools two of Cotman’s tutors were Frederick Leighton and the miniature and portrait painter Henry Tamworth Wells. Leighton employed Cotman to help paint The Daphnephoria in 1876, a composition of thirty-six figure which depicted the festival in ancient Thebes to celebrate a victory over the Aeolians. It was held every ninth year in honour of Apollo; at head of procession a pole is carried bearing several copper globes, the largest representing the sun or Apollo, the next largest the moon and the small globes the stars and planets.

One of the Family by Frederick George Cotman (1880)

The Widow by Frederick George Cotman (1880)

Cotman became recognised as a London society portrait painter, and such paintings could fetch a fee of three hundred guineas. He also completed many homely genre scenes. Cotman was elected a member of both the Royal Institute of Painters In Water Colours and the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, and his paintings graced the walls of the Royal Academy, the Royal Society of British Artists; Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours; Agnew & Sons Gallery; the Dudley Gallery; Dowdeswell Gallery; Fine Art Society; Grosvenor Gallery all in London, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool; Manchester City Art Gallery; the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts and the Royal Scottish Academy.

Alderman William Groom by Frederick George Cotman (1903)

Frederick married at St Mary Abbots, Kensington, London on March 30th 1875. His wife was a Scottish girl, Ann Barclay Grahame, who was the daughter of Barron Grahame, of Morphie, Aberdeenshire. It was also in 1875 that Frederick became a founder member of the Ipswich Fine Art Club. In 1891, Frederick with his wife and six children were living at Widmere Common, Burnham, Buckinghamshire but in 1897 he moved to Lowestoft, Suffolk to enjoy his favourite sport of yachting. Frederick George Cotman died at Quilter Road, Felixstowe on July 16th 1920, a month before his seventieth birthday. He was buried in Old Felixstowe churchyard. His wife died in 1936, aged 86.

Henry George Todd

Henry George Todd was born at 27 St John’s Street, Bury St Edmund’s on January 20th 1847. He was the son of George Todd, who plied his trade as a decorative artist and signwriter, and his wife Sophia Todd (née Spencer). Henry attended a school at Bury St Edmund’s and later Henry was apprenticed to his father and trained in decorating, gilding and signwriting. At the age of 18, Henry enrolled in an art school and due to his excellent work he went on to enrol at the South Kensington Schools, which is now known as the Royal College of Art.

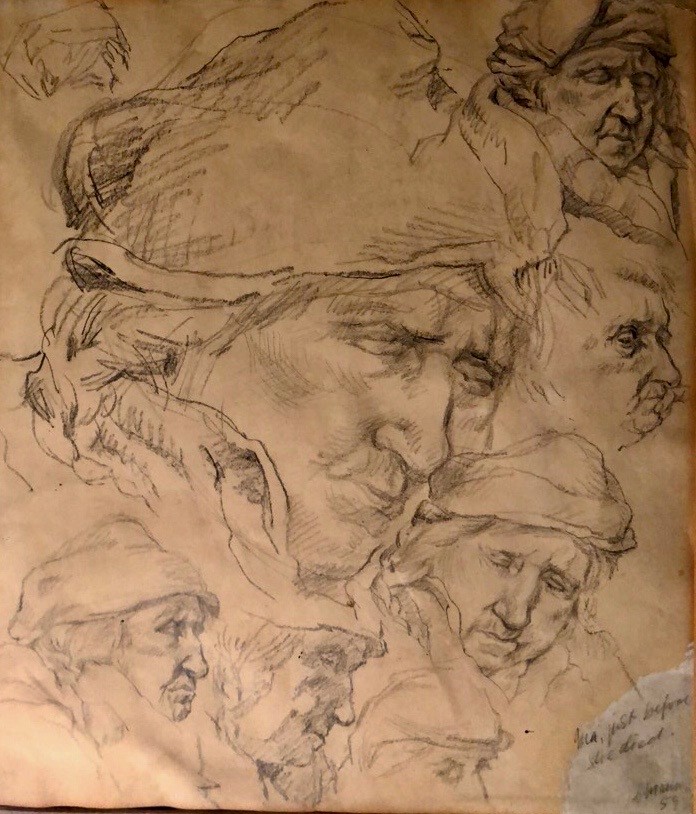

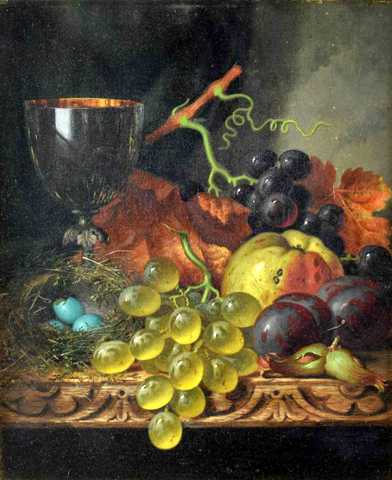

Still life with Fruit and a Ewer on a Stone Ledge by Henry George Todd

Still life by Henry George Todd

Later both he and his father exhibited their works in the Todd’s St Andrew’s Street North shop. Around 1874, twenty-seven-year-old Henry moved to Ipswich and got a job with Alfred Stearn & Son, which was then the most important decorating company in the town, working in design, decoration, and gilding, being commissioned by local traders for their shopfronts which were considered by many as works of art.

Gainsborough Lane, Ipswich by Henry George Todd

Although Henry was working full time at the business, he still found time to paint. His favoured genres were his still life pictures and Suffolk landscapes. Henry Todd married 21-year-old Ellen Lucy Quinton of Ipswich and the couple went on to have five children; Ada Ellen who was born in 1874, George William in 1875, Eva Spencer in 1876 and Arthur John in 1880, sadly their 16-month-old daughter, Kate Sophia died in 1882. He joined the Ipswich Fine Art Club in 1885 and became largely famous for his still-life and his aptitude to paint grapes.

Seaweed Gatherers by Henry George Todd

Todd exhibited at many shows including one painting at the Royal Academy also displayed his work at the Suffolk Street Gallery of the Royal Society of British Artists, and the Dudley Gallery. Henry George Todd died in Croft Street, Ipswich on June 30th 1898, aged 51 and was buried in Ipswich cemetery five days later.

Once again the information for Part 2 of the Suffolk Artists was gleaned from two excellent websites;

and also the book by Chloe Bennett entitled Suffolk Artists (1750-1930).