The story of The Rose Girls could not be told without talking about the American illustrator and author, primarily of books for young people, Howard Pyle, who gave the The Rose Girls soubriquet to the three young ladies he was mentoring. He was a man of great talent and a patriotic missionary of Americanism and his illustrations were held in high esteem on both sides of the Atlantic..

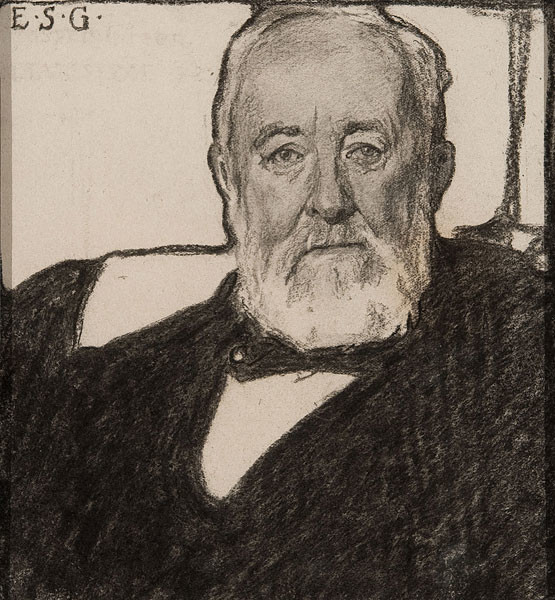

Howard Pyle was born in Wilmington, Delaware on March 5th 1853. He was the son and eldest child of Quakers, William Pyle and Margaret Churchman Painter, an amateur artist. Pyle remembered his childhood, with fondness, as being an idyllic time that was centred around the family’s wonderful old stone house and its garden, which he remembered as being filled with profuse blooms and hidden wonders. Mainly thanks to his mother, Pyle developed a love of reading and like many children of his age he loved the tales of Daniel Defoe’s,such as Robinson Crusoe, the Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and mystical stories from the Arabian Nights. all of which fired up his young imagination. He attended the Friend’s School in Wilmington followed by schooling at a small private institution. He was not a top student, and it was said that he wasted too much time daydreaming. His one love was art and he spent much of his free time drawing. He also developed a love of writing his own stories. Although it was the wish of Pyle’s parents that their son should attend college, Howard Pyle had other ideas about his future, which he saw as being a professional artist or writer. Knowing that their son was never going to go to university his parents, especially his mother, decided to encourage him to study art.

He studied for three years at the studio of Francis Van der Wielen in Philadelphia. Van der Wielen was a Dutch artist who in 1872 had taught sixteen-year-old Cecilia Beaux. Besides a few art lessons later at the Art Students League of New York, these three years tutoring by van der Wielen were Howard Pyle’s only formal training. Because of problems with his father’s leather business, Howard Pyle had to spend many years helping out in the family business. The artistic breakthrough for Howard Pyle came in 1876 when his mother sent an essay and sketches he had done while on holiday with his father on Chincoteague Island to Scribner’s Magazine. The editor accepted the article and illustrations and told Pyle they were so good that they were being published in the November issue of the magazine. Furthermore, the editor invited Howard Pyle to come to New York and work for the magazine as a writer and illustrator.

Howard Pyle was now living in New York city in a small rented room at 250 West 38th Street (between Seventh and Eighth Avenues) and it was not long before he sold his first painting to Harpers Weekly, a magazine that would continue to buy his work for many years in the future. The publisher of Harper’s Weekly had assembled an exceptional group of professionals who were knowledgeable about illustration and trained in the newest methods of printing, and the House of Harper became an informal training ground for the likes of Howard Pyle to learn every aspect of the publishing process. It was soon after settling in New York that Howard Pyle knew that he wanted to write and illustrate books for children. Pyle had both a wonderful imagination and he also was able to recollect stories from his childhood. He set about putting those memories on paper and at the same time illustrated his prose. He submitted many of his stories and illustrations to the St Nicholas magazine, a popular monthly American children’s magazine, founded by Scribner’s in 1873.

He drew upon his vivid childhood memories to contribute stories to the St. Nicholas magazine, and he read and studied many of the old folktales that he’d loved as a child, extending his reading to include less familiar tales from many nations. These folktales and the romances of his boyhood would become the central core of his work over his lifetime; and although he is primarily remembered today for his contributions to illustration, he was a writer of some skill. Indeed, he has been compared to Hans Christian Andersen in the way his unique voice and imagination shaped his traditional folklore and fantasy material.

According to Ian Schoenherr’s blog on Howard Pyle, one of the first magazine covers to feature an illustration by Howard Pyle is the May 1877 cover of St. Nicholas, Scribner’s Illustrated Magazine for Girls & Boys. Pyle actually only designed the long rectangular illustration which runs diagonally across the cover. In the magazine the publisher explained the illustration:

“…The beautiful tablet by Mr. Pyle, which adorns our cover this month, tells a true story in its own lively fashion. Its quaint costumes of successive centuries, showing how May-day rejoicings have been kept up from age to age, will send some of you a-Maying in encyclopedias and year-books, but it gives its real meaning at a glance – which is, that through all time people have welcomed the first coming of the spring. “Merrie May,” meaning pleasant May (for in old times “merry” simply meant pleasant), was as fresh and beautiful ages ago as it is to-day; and in one way or another the thought at the bottom of all the rejoicing is ever that of the old carol:

“A garland gay I’ve brought you here,

And at your door I stand;

It’s but a sprout, but it’s well budded out.

The work of our Lord’s hand.”

Howard Pyle remained in New York until 1879 at which time he returned home to Wilmington, by which time he had established a reputation as a leading writer and illustrator of children’s books.

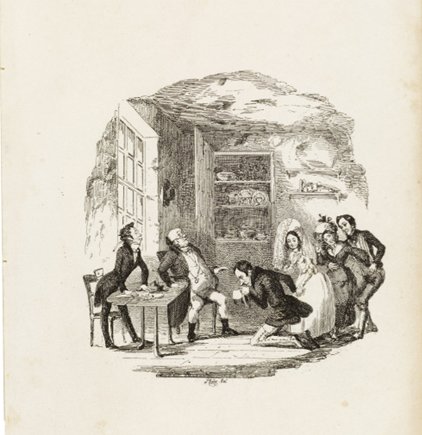

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire, published in 1883, is thought to have been Pyle’s first children’s book. He wrote, illustrated and designed the book himself. In all, he went on to do many more books for this audience including Pepper and Salt, The Wonder Clock and four volumes of the Legends of King Arthur.

He completed Legend and Stories of King Arthur in 1903. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle’s novel begins with King Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.

He completed Legend and Stories of King Arthur in 1903. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle’s novel begins with King Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.

Howard Pyle believed that book illustration was the fundamental basis from which to produce painters. His ideas with regards illustration were revolutionary and at odds with many of the beliefs of the day. Pyle was adamant that artists needed, to get beyond the stiff figures of the studio life class and let their figures and scenes come from the imagination rather than from a frozen pose.

For Pyle, the overall design of the book was of paramount importance and he helped his students learn how to incorporate their illustrations into the finished article. Pyle made it clear to his students that the role of the illustrator was to compliment and enhance the text in personal ways rather than merely mimic what the text expressed. Through his many books and his teaching, the influence of Howard Pyle on children’s literature is acknowledged by readers and artists to this day.

Pyle decided to do something about giving art students a firmer foundation in illustrative art by offering his services to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art as their Instructor of Illustration. His offer was politely refused and he was told that the Academy school was for painters and sculptors and was a school for the fine arts only. Pyle, having been rebuffed by the Academy, was not to be deterred and made the same offer to the Drexel Institute. His offer was promptly accepted and within a short time there began to appear in the magazines new names of illustrators who had been students of Pyle. Sensing that the Drexel Institute was the better option when it came to illustrative art, many of the Pennsylvania Academy students left and enrolled at the Drexel Institute. The director of the Pennsylvania Academy, Harrison Morris, realised he had been wrong to rebuff Pyle’s offer, and asked him to come and teach at the Academy and name his own salary. Pyle’s short reply was to the point:

“…He who will not when he may, when he will, he shall have nay…”

Howard Pyle commenced teaching at the Drexler Institute in October 1894. The catalogue of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts (1894-1895) announced:

“…A Course in Practical Illustration in Black and White, under the direction of Mr. Pyle. The course will begin with a series of lectures illustrated before the class by Mr. Pyle. The lectures will be followed by systematic lessons in Composition and Practical Illustration, including Technique, Drawing from the Costumed Model, the Elaboration of Groups, treatment of Historical and other subjects with reference to their use in Illustrations. The students’ work will be carefully examined and criticized by Mr. Pyle…”

Within Howard Pyle’s first class that October, there were thirty-nine students, including three young people destined to become outstanding leaders in the field of illustration: Maxfield Parrish, Jessie Willcox Smith, and Elizabeth Shippen Green. Three years later, in 1897, Violet Oakley joined the class.

………..to be continued.

Most of the information I used for this blog came from an excellent book by Alice A. Carter entitled The Red Rose Girls, An Uncommon Story of Art and Love.

On a more personal note, it is ten years to the day that I started My Daily Art Display blog and this is 830th “edition”. It started as a one-a-day blog but they were shorter blogs and I was finding I was putting too much pressure on myself to meet deadlines so I now do just one a week but have increased the number of words. I do enjoy writing them and hopefully will carry on a little while longer.

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

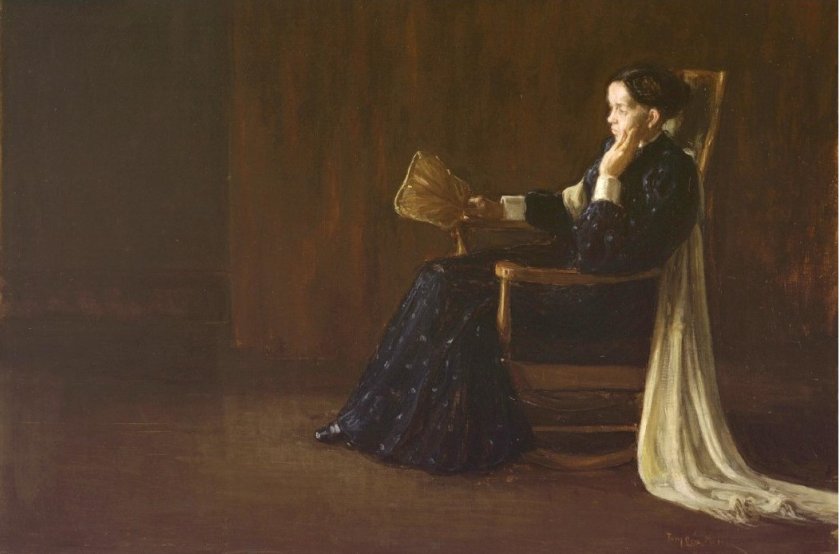

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

The painting became the first work by an African American artist to join the White House permanent collection.

The painting became the first work by an African American artist to join the White House permanent collection.

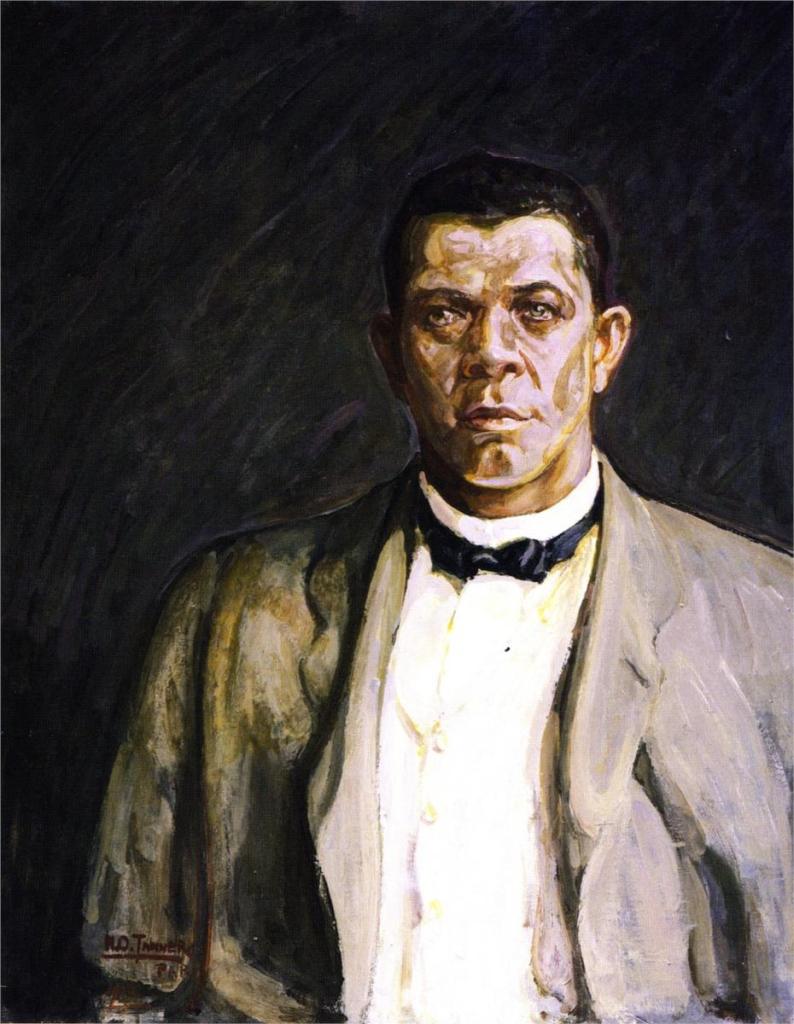

In 1893, Tanner went back to the United States to deliver a paper on African Americans and art at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In this same year, he created one of his famous works The Banjo Lesson while he was in Philadelphia. His depiction incorporated a series of sketches he had made while visiting the Blue Ridge Mountains, four years earlier. The sketches he had made during the summer of 1888 had opened his eyes to the poverty of African Americans living in Appalachia.

In 1893, Tanner went back to the United States to deliver a paper on African Americans and art at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In this same year, he created one of his famous works The Banjo Lesson while he was in Philadelphia. His depiction incorporated a series of sketches he had made while visiting the Blue Ridge Mountains, four years earlier. The sketches he had made during the summer of 1888 had opened his eyes to the poverty of African Americans living in Appalachia.

The mural on the north wall, to the left of the Hearing Room shows King John of England sealing and granting Magna Charta (the Great Charter) in June 1215 on the banks of the Thames River at the meadow called Runnymeade. His reluctance to grant the Charter is shown by his posture and sullen countenance. But he had no choice. The barons and churchmen led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, forced him to recognize principles that have developed into the liberties we enjoy today. King John, out of avarice, greed or revenge, had in the past seized the lands of noblemen, destroyed their castles and imprisoned them without legal cause. As a result, the noblemen united against the king. Most of the articles in Magna Charta dealt with feudal tenures, but many other rights were also included.

The mural on the north wall, to the left of the Hearing Room shows King John of England sealing and granting Magna Charta (the Great Charter) in June 1215 on the banks of the Thames River at the meadow called Runnymeade. His reluctance to grant the Charter is shown by his posture and sullen countenance. But he had no choice. The barons and churchmen led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, forced him to recognize principles that have developed into the liberties we enjoy today. King John, out of avarice, greed or revenge, had in the past seized the lands of noblemen, destroyed their castles and imprisoned them without legal cause. As a result, the noblemen united against the king. Most of the articles in Magna Charta dealt with feudal tenures, but many other rights were also included. The mural on the west wall over the entrance to the Hearing Room depicts an incident in the reign of Caesar Augustus Octavius. The Roman writer Seutonious tells of Scutarious, a Roman legionnaire who was being tried for an offense before the judges seated in the background. The legionnaire called on Caesar to represent him, saying: “I fought for you when you needed me, now I need you.” Caesar responded by agreeing to represent Scutarious. Caesar is shown reclining on his litter borne by his servants. Seutonious does not tell us the outcome of the trial but leaves us to surmise that with such a counsellor he undoubtedly prevailed. The mural represents Roman civil law, which is set forth in codes or statutes, in contrast to English common law, which is based not on a written code but on ancient customs and usages and the judgments and decrees of the courts which follow such customs and usages.

The mural on the west wall over the entrance to the Hearing Room depicts an incident in the reign of Caesar Augustus Octavius. The Roman writer Seutonious tells of Scutarious, a Roman legionnaire who was being tried for an offense before the judges seated in the background. The legionnaire called on Caesar to represent him, saying: “I fought for you when you needed me, now I need you.” Caesar responded by agreeing to represent Scutarious. Caesar is shown reclining on his litter borne by his servants. Seutonious does not tell us the outcome of the trial but leaves us to surmise that with such a counsellor he undoubtedly prevailed. The mural represents Roman civil law, which is set forth in codes or statutes, in contrast to English common law, which is based not on a written code but on ancient customs and usages and the judgments and decrees of the courts which follow such customs and usages. The mural on the south wall portrays the trial of Chief Oshkosh of the Menominees for the slaying of a member of another tribe who had killed a Menominee in a hunting accident. It was shown that under Menominee custom, relatives of a slain member could kill his slayer. Judge James Duane Doty held that in this case territorial law did not apply. He stated:

The mural on the south wall portrays the trial of Chief Oshkosh of the Menominees for the slaying of a member of another tribe who had killed a Menominee in a hunting accident. It was shown that under Menominee custom, relatives of a slain member could kill his slayer. Judge James Duane Doty held that in this case territorial law did not apply. He stated: The fourth mural, which is actually the first one that is visible on making an entrance to the Supreme Court Room, and is Albert Herter’s rendition of the signing of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. George Washington is shown presiding. On the left, Benjamin Franklin is easily recognizable. On the right, James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” is shown with his cloak on his arm. Although he was in France at the time, Thomas Jefferson was painted into the mural because of his great influence on the principles of the Constitution. The painting hangs above the place where the seven member Wisconsin Supreme Court sit to hand down their decisions. The mural’s position above the bench is symbolic that the Supreme Court operates under its aegis and is subject to its constraints. The United States Constitution has served us well for more than 200 years. This mural shows our indebtedness to federal law.

The fourth mural, which is actually the first one that is visible on making an entrance to the Supreme Court Room, and is Albert Herter’s rendition of the signing of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. George Washington is shown presiding. On the left, Benjamin Franklin is easily recognizable. On the right, James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” is shown with his cloak on his arm. Although he was in France at the time, Thomas Jefferson was painted into the mural because of his great influence on the principles of the Constitution. The painting hangs above the place where the seven member Wisconsin Supreme Court sit to hand down their decisions. The mural’s position above the bench is symbolic that the Supreme Court operates under its aegis and is subject to its constraints. The United States Constitution has served us well for more than 200 years. This mural shows our indebtedness to federal law.

The mural on the left was a scene from the court case against a local magistrate, Samuel Sewall. In 1692 a small group of men and women of Salem were arrested for bewitching their neighbours. Samuel Sewall, a local magistrate, was a member of the court that ultimately sentenced nineteen people to be hanged. The tragedy was realised several months later: those still being held were released. In the mural, Sewall is seen standing in Old South Church in Boston with his head bowed as his confession and prayers for pardon are read aloud.

The mural on the left was a scene from the court case against a local magistrate, Samuel Sewall. In 1692 a small group of men and women of Salem were arrested for bewitching their neighbours. Samuel Sewall, a local magistrate, was a member of the court that ultimately sentenced nineteen people to be hanged. The tragedy was realised several months later: those still being held were released. In the mural, Sewall is seen standing in Old South Church in Boston with his head bowed as his confession and prayers for pardon are read aloud.