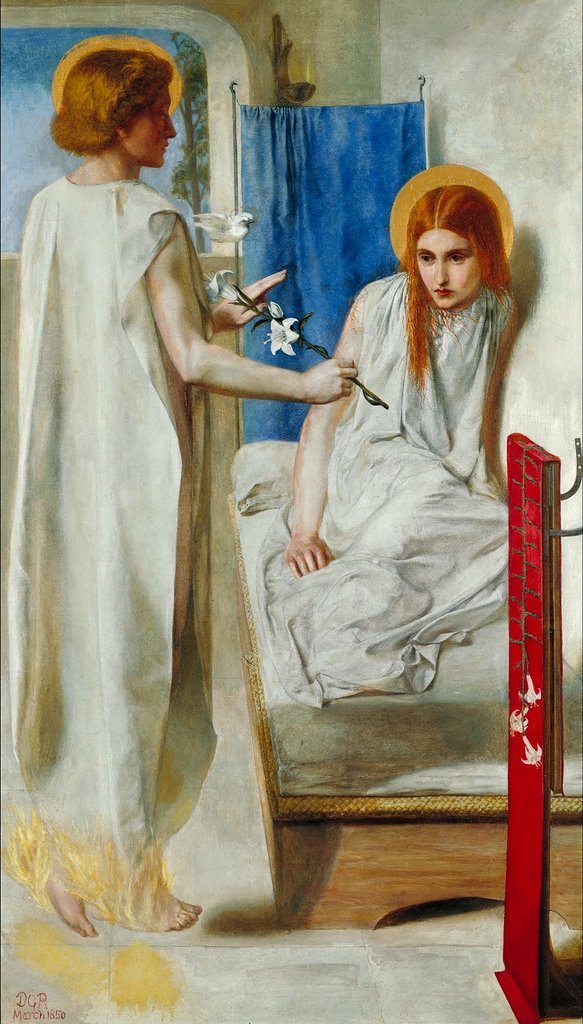

My Daily Art Display today is, like my last offering, another painting depicting a scene from the Bible. The scene is The Annunciation and has featured in paintings by many of the Renaissance Masters. However this painting by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Rossetti has some subtle differences from these earlier works by the likes of Fra Angelico, Raphaello Santi, El Greco, van Eyck and Botticelli.

The story of the Annunciation is probably known by most and it is documented in the bible in the book of Luke (1: 26-38)

26 In the sixth month of Elizabeth’s pregnancy, God sent the angel Gabriel to Nazareth, a town in Galilee, 27 to a virgin pledged to be married to a man named Joseph, a descendant of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. 28 The angel went to her and said, “Greetings, you who are highly favoured! The Lord is with you.”

29 Mary was greatly troubled at his words and wondered what kind of greeting this might be. 30 But the angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary; you have found favour with God. 31 You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. 32 He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, 33 and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever; his kingdom will never end.”

34 “How will this be,” Mary asked the angel, “since I am a virgin?”

35 The angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come on you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. So the holy one to be born will be called[a] the Son of God. 36 Even Elizabeth your relative is going to have a child in her old age, and she who was said to be unable to conceive is in her sixth month. 37 For no word from God will ever fail.”

38 “I am the Lord’s servant,” Mary answered. “May your word to me be fulfilled.” Then the angel left her.

The painting I am featuring today is entitled The Annunciation which Rossetti painted in 1850. That was not its original title given to it by the artist, Gabriel Rossetti. He had originally decided to call the painting Ecce Ancilla Domini meaning “behold the handmaid of the Lord” but at the last moment changed his mind. In the painting, Rossetti has just used the three primary colours, red, blue and yellow along with white. The use of these colours by the artist is symbolic. We have white for feminine purity, blue for the Virgin Mary, red for the Passion of Christ and yellow or gold which symbolises holiness. There are other things in the painting which are symbolic. The Angel Gabriel holds a lily and in the foreground we see a red cloth on to which we can see that Mary has embroidered white lilies. Maybe this signifies the young girl’s decision to live a very pure life.

Mary and her mother, St Anne, can be seen embroidering that very cloth in Rossetti’s painting The Girlhood of Mary Virgin which he painted a year earlier. Lilies symbolize purity, chastity, and innocence and white lilies represent the purity of the Virgin Mary. In most paintings of the Annunciation we see the Angel Gabriel presenting Mary with a white lily when he announced to her that she would give birth to the Son of God.

The setting Rossetti has given this scene is very unusual. In Renaissance paintings of The Annunciation we look at settings which are sumptuous. Tapestries and heavy velvet curtains often abound. Light frequently can be seen entering the scene through exquisite stained glass windows lighting up elaborate furnishings and floor coverings. Rossetti chose not to go down that line. As we look upon the scene the first thing that strikes us is the claustrophobic compactness of Mary’s room. It could almost be termed minimalistic in its accoutrements. Look at the window opening on the back wall. There was no attempt by Rossetti to give a feeling of depth to this painting by depicting a town somewhere in the far distance. The window opening is plain and uncovered and through it we just see part of a solitary tree against a blue sky, the colour of which mirrors that of the colour of the screen at the end of Mary’s bed.

In most depictions of this scene we see Mary dressed in blue robes quietly and in some cases joyously receiving the news that she will give birth to the Christ child. However Rossetti has depicted Mary’s mood differently. We see Mary dressed in a white shift dress shrinking back from the Angel Gabriel. Rossetti has added the colour blue which is associated with the Virgin Mary in the form of a blue cloth screen hanging behind her.

Rossetti has also included a dove which embodies the Holy Spirit. He has depicted the golden-haired Angel Gabriel without wings, which was the norm for Annunciation paintings. Gabriel’s face is in shade and his facial features are almost hidden from us. He can be seen in this painting hovering just above the floor with flames all around his feet. I wonder if I am just imagining it but it looks as if he is pointing the lily stem at Mary’s womb. It is little wonder that the combination of his words and this action make the young girl almost cower and recoil against her bedroom wall.

Take a while and look at Mary’s expression. How do you read Rossetti’s depiction of this young woman? Look at her facial expression. This is not one of acquiescence or pleasure. This is a look almost of horror at what she has just been told. This terrified look adds a great deal of power to Rossetti’s painting. Mary herself in Rossetti’s painting looks much younger than we are used to seeing in similar scenes. She exudes a youthful beauty but only seems to be a mere adolescent with her long un-brushed auburn hair contrasting sharply with her white dress. She is painfully thin and her hesitance and sad look tinged with fear endears her to us. We can empathize with her situation. Rossetti through this painting wants us to put ourselves in the position of Mary at hearing the news of what has been mapped out as her future. The various Christian religions would have us believe that Mary has been honoured by being chosen as the future Mother of God but Rossetti is asking us to consider carefully whether this young girl, Mary, has been given a wonderful opportunity or whether her life has been saddled with an onerous responsibility. You need to study her face and decide for yourself. The model for Mary was Christina Rossetti, the poet, and the artist’s sister

I believe a number of the “standard” Annunciation paintings were meant to inspire us to lead a “good” life and for that reason we see the Virgin Mary delighted to be given the role as Mother of God. The “standard” depiction of Mary with her happy smiling face leads us to believe that leading a pure and holy life will give us similar pleasure. However Rossetti’s depiction of the Annunciation questions Mary’s happiness to accept her future role in life. It is a role that will take away many of the pleasures a young girl would be looking forward to enjoying as she enters adulthood.

I suppose how you look at the painting and how you interpret what you see will depend on your religious belief.