Over the next two blogs I want to introduce you to and look at the life of one of the finest 18th century French female portraitist, Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun. In my initial blog about her I want to examine her early life and show you three of her self portraits and in the following blog I will conclude her life story and tell you about her friendship with Marie-Antoinette, her exile from the land of her birth and relate how I was once again unfaithful having been seduced by a new beauty ! Sounds interesting ?

by Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1782)

Today’s artist was born Élisabeth-Louise Vigée in April 1755 on the rue Coquilliere in Paris, just six months before another baby girl was born in the palace of Emperors of Austria in Vienna, a priveleged child, who would become the queen of the French nation and also play a large part in Élisabeth’s life. That Viennese baby was Marie-Antoinette. But let me return to Élisabeth. Élisabeth was the daughter of Louis Vigée, a portraitist and professor at the Academie de Saint Luc . Her mother, Jeanne Maissin was a hairdresser by trade. At the age of 3 months, she was sent to a small farm near Épernon, where she was looked after by relatives. She stayed with them until she was six years old. Following this, she attended the convent school, Couvent de la Trinite in the Faubourg Saint Antoine district of Paris, as a pensionnaire, (a boarder) where she remained until she was twelve years old. It was here that she first displayed her young talent for drawing and painting. In her memoirs she wrote about her time at the boarding school, her love of drawing and the trouble it often got her into but also the pleasure her father had in her interest in art. She wrote:

“….During that time I scrawled on everything at all seasons; my copy-books, and even my schoolmates’, I decorated with marginal drawings of heads, some full-face, others in profile; on the walls of the dormitory I drew faces and landscapes with coloured chalks. So it may easily be imagined how often I was condemned to bread and water. I made use of my leisure moments outdoors in tracing any figures on the ground that happened to come into my head. At seven or eight, I remember, I made a picture by lamplight of a man with a beard, which I have kept until this very day. When my father saw it he went into transports of joy, exclaiming, “You will be a painter, child, if ever there was one!…”

On returning to live at home on a permanent basis, her father gave Élisabeth her first drawing lessons when she was allowed to attend his drawing classes which he gave to students in his studio. Sadly his tuition did not last long as Louis Vigée died on May 9 1767 in his apartment on the rue de Clery. To lose her father at the age of twelve was a traumatic experience for Élisabeth and she recalled the moment:

“…I had spent one happy year at home when my father fell ill. After two months of suffering all hope of his recovery was abandoned. When he felt his last moments approaching, he declared a wish to see my brother and myself. We went close to his bedside, weeping bitterly. His face was terribly altered; his eyes and his features, usually so full of animation, were quite without expression, for the pallor and the chill of death were already upon him. We took his icy hand and covered it with kisses and tears. He made a last effort and sat up to give us his blessing. “Be happy, my children,” was all he said. An hour later our poor father had ceased to live…”

by Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1786)

Élizabeth’s father had, on his death, left the family penniless and his widow had to find ways of clearing their debts and pay for her son’s schooling and it is with that in mind that, in December of that same year, 1767, she married a wealthy jeweller, Jacques François Le Sevre and the family moved to an apartment on the rue Saint Honore facing the Palais Royal. However any thoughts she had that her rich husband would solve the family’s financial problems were soon dashed as he turned out to be miserly with his money and just provided the bare minimum for his wife and her son. Élisabeth, by this time, had been earning her own money from commissions but was made to hand it over to her step-father for him to use as he saw fit.

Élisabeth began taking drawing lessons with her friend Blaise Bocquet from the history painter and Academician, Gabriel Briard, who had a studio in the Louvre. During her training she copied the paintings of the Old Masters at the Louvre and the Palais-Royal, which housed the magnificent Orléans art collection, and during this period she encountered the French artist, Claude Joseph Vernet. He would often give her artistic advice and encourage her and more importantly introduced her to prospective important and wealthy patrons. She also met the Abbé Arnault, of the French Academy. She later described him as a man of strong imaginative gifts, with a passion for literature and the arts and recalled how his conversation enriched her with ideas. It was the studying of the Old Masters’ paintings which furthered her knowledge of anatomy, perspective, and the other important aspects of history painting which she was not allowed to formally study, simply because of her gender. She spent a great deal of time copying the heads in some of the pictures by Rubens, Rembrandt and Van Dyck, as well as several heads of girls in paintings by Jean-Baptiste Greuze. She was a great admirer of Greuze’s portraiture because, from them, she learnt about his use of the demi-tints when portraying flesh colouring.

By this time Élisabeth had decided that her future lay in her art and she would strive to become a successful painter. However her choice of career was problematic simply because she was a female. As a female, she was excluded from formal academic training and artistic competitions and this factor alone gave her a distinct disadvantage in comparison to the training afforded to her male contemporaries. At this time in France, the most prestigious type of painting was history painting but to achieve a reputation as a great history painter one had to undergo an all-embracing formal artistic education into the likes of the technique of painting the nude male and how to best arrange figures within a painting for it to be accepted as an acceptable narrative work. However for reasons of modesty, females were not allowed to paint nude males and so as this formal training was not yet available to aspiring female artists, they had to settle for painting portraits, landscapes and genre works. She now decided to specialise in portraiture.

by Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1789)

In 1774, aged nineteen, Élizabeth applied to join the Academy of Saint Luke where her father had taught. She was accepted and that year she exhibited several of her works at their Salon. Her portraiture and the way in which she depicted her sitters in a flattering manner was very popular and much in demand. In 1775 she married a wealthy art dealer and amateur painter, Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun. The marriage was a marriage of convenience orchestrated by her mother. Five years later, the couple had their only child, Jeanne Julie Louise, born on February 12th 1780. It was not a love match, but more of a mutually-beneficial pact that benefitted them both. . Her husband marketed her work and endorsed her artistic career while also profiting from her artistic output. It worked well and the couple became quite affluent and lived a luxurious lifestyle, which allowed them to mix socially with the highest circles of society. Soon Élisabeth and her husband would hold fashionable soirées at their home. Their guests included artists, writers, and important members of Parisian society. In 1776 she finally managed to achieve her ultimate aim. She secured her first royal commission when she was asked to paint a series of portraits of King Louis XVI’s brother, the Comte de Provence. Before long she even caught the attention of the king and queen themselves and Élisabeth was summoned to the court in 1778 to paint her first portrait of the Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette had had her portrait painted by many artists but neither she nor her mother, Marie-Thérèse were ever fully satisfied with the results. However, they both approved of Élisabeth’s depiction which, although it admirably conveys her royal status, it was actually much more simplified and natural than most of the earlier official portraits of the queen. This portrait marked the start of a close relationship between Élisabeth and Marie-Antoinette. This relationship greatly enhanced the reputation of the artist and led to many wealthy commissions. Louis XVI was equally impressed by her artistic work and in Wendy Slatkin’s book, Women Artists in History, she quotes Louis XVI’s comments about Élisabeth and her work:

“…I know nothing about painting, but you have made me love it…”

Élisabeth was a devoted royalist and idolized Marie Antoinette and the rest of the royal family. It was however this close friendship with Marie-Antoinette which was to alter the course of her life.

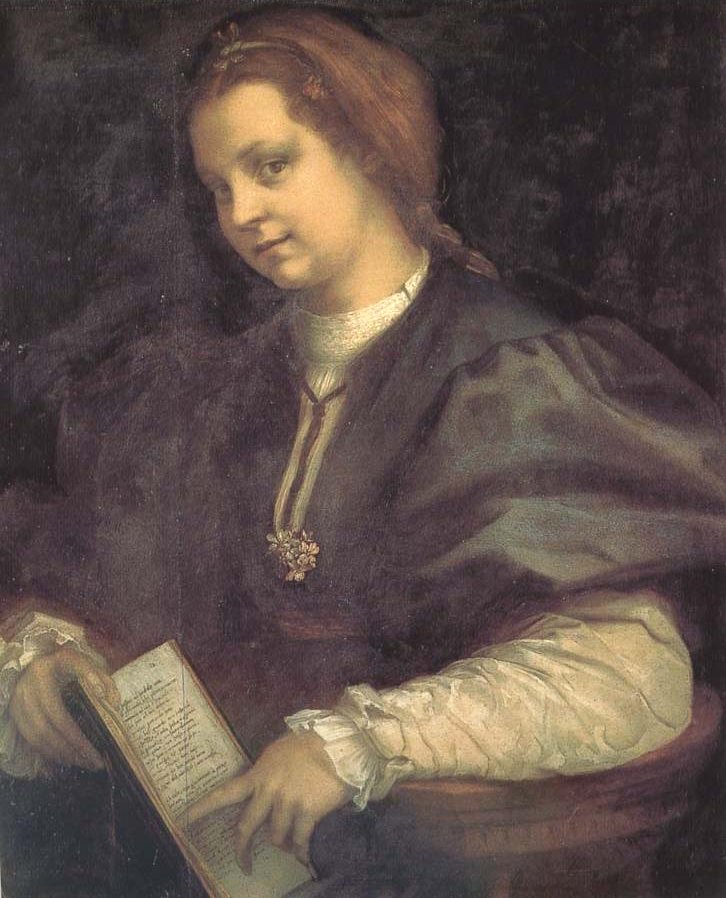

Portrait of Susan Lumsden by Rubens

Portrait of Susan Lumsden by Rubens

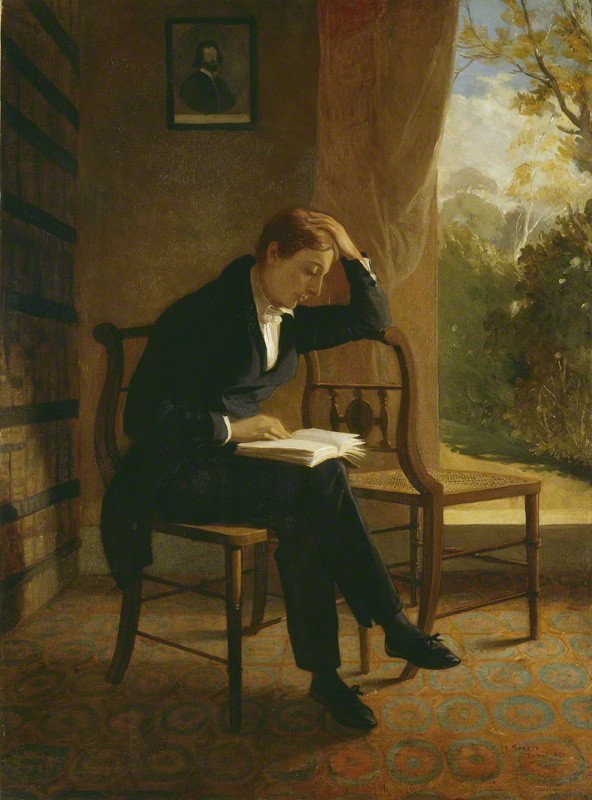

I have included three self portraits in this intial blog about the artist Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun. The first one entitled Self Portrait with Straw Hat was completed in 1782 and is held in a Swiss private collection. Élisabeth exhibited this work at the 1783 Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), Paris. Of this painting the artist wrote:

“…I was so delighted and inspired by Rubens’ Le Chapeau de Paille that I completed a self portrait whilst in Brussels in an effort to achieve the same effect. I painted myself wearing a straw hat with a feather and a garland of wild flowers and holding a palette in one hand...”

For a more comprehensive look at Rubens’ Le Chapeau de Paille, also known as Portrait of Susanna Lunden go to My Daily Art Display of March 11th 2011.

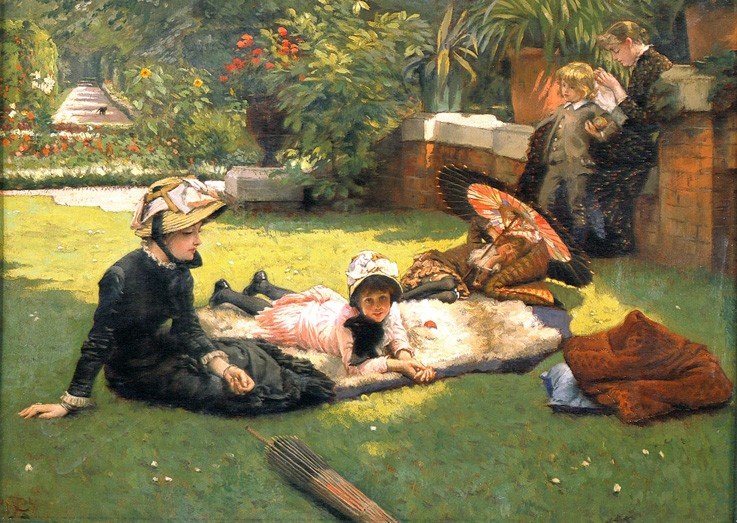

The second self portrait I have featured was completed by Élisabeth in 1786 and is entitled Madame Vigée-Le Brun and Her Daughter, Jeanne-Lucie, known as Julie (1718–1819). The painting is thought to have been inspired by a work by Angelika Kaufmann, entitled Lady Hervey and her Daughter which depicted Elizabeth Drummond, Lady Hervey and her daughter Elizabeth Catherine Caroline Hervey later to become The Honourable Mrs Charles Rose Ellis. The work by Vigée Le Brun is one of maternal tenderness and is somewhat reminiscent of the sentimental pictures of Jean-Baptiste Greuze which Élisabeth had studied in her younger days.

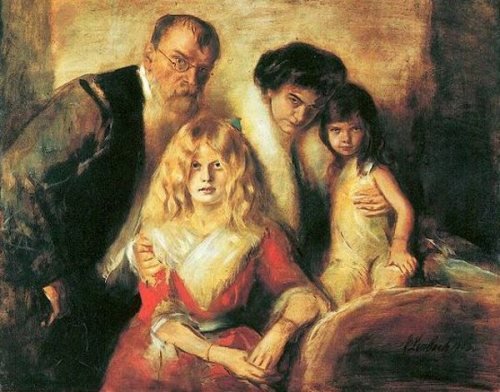

The third portrait in this blog is entitled Madame Vigée-Le Brun et sa fille, Jeanne-Lucie-Louise, dite Julie (Madame Vigée-Le Brun and her daughter Jeanne-Lucie-Louise, known as Julie) and is often referred to as Self Portrait with Daughter (à la Grecque). It is currently housed at the Louvre in Paris.