Mark Gertler

Gertler had now settled into life at the Slade art academy. One of his fellow students, C.R.W Nevinson summed up life at the Slade when he and Gertler were students there saying it was full with a crowd of men such as I have never seen before or since.. As far as his thoughts on Gertler, he once wrote that Max was the genius of the place… and the most serious, single-minded artist he had ever come across. Gertler was considered the best draughtsman to study at the Slade since Augustus John. Another student, Paul Nash, said that Gertler riding high “upon the crest of the wave”.

Still life with a Bottle of Benedictine by Mark Gertler

In 1910 a new seventeen-year-old student arrived at the Slade Academy of Art who was to add a little “spice” to the lives of Gertler and some of the other students. Dora de Houghton Carrington, who after joing the Slade, became known simply by her surname, Carrington, as she considered Dora to be vulgar and sentimental. Gertler and C.R.W. Nevinson both became closely attached to Carrington and according to Michael J. K. Walsh 2002 biography, C. R. W. Nevinson: The Cult of Violence, he wrote about that impossible situation:

“…What he (Nevinson) was not aware of was that Carrington was also conversing, writing and meeting with Gertler in a similar fashion, and the latter was beginning to want to rid himself of competition for her affections. For Gertler the friendship would be complicated by sexual frustration while Carrington had no particular desire to become romantically involved with either man…”

This was unfortunate as Gertler and Nevinson had become great friends. Gertler wrote to his sponsor, William Rothenstein saying:

“…My chief friend and pal is young Nevinson, a very, very nice chap. I am awfully fond of him. I am so happy when I am out with him. He invites me down to dinners and then we go on Hampstead Heath talking of the future…”

In Michael J. K. Walsh’s biography of Nevinson, Hanging a Rebel: The Life of C.R.W. Nevinson, he wrote:

“…Together they studied at the British Museum, met in the Café Royal, dined at the Nevinson household, went on short holidays and discussed art at length. Independently of each other too, they wrote of the value of their friendship and of the mutual respect they held for each other as artists…”

C.R.W. Nevinson, himself, wrote of his friendship with Gertler in his 1937 autobiography, Paint and Prejudice:

“…I am proud and glad to say that both my parents were extremely fond of him.” Henry Nevinson recalled: “Gertler came to supper, very successful, with admirable naive stories of his behaviour in rich houses and at a dinner given him by a portrait club, how he asked to begin because he was hungry…”

Gertler pursued Carrington for a number of years, and they had a brief sexual relationship during the years of the First World War.

Portrait of a Girl ( Gertler’s Sister, Sophie) by Mark Gertler (1908-1911)

As is the case for many young aspiring portrait artists, Gertler, before he painted commissioned works, began by painting portraits of family members. One of his most frequent depictions was of his mother.

The Artist’s Mother by Mark Gertler (1913)

In this painting of his mother Golda Gertler has depicted her as a peasant with huge, working hands. He called the portrait ‘barbaric and symbolic’, explaining that it was meant to show ‘suffering and a life that has known hardship’.

The Artist’s Mother by Mark Gertler (1911)

Gertler once wrote rather disparagingly about his sitter:

“… “I am painting a portrait of my mother. She sits bent on a chair, deep in thought. Her large hands are lying heavily and wearily in her lap. The whole suggests suffering and a life that has known hardship. It is barbaric and symbolic. Where is the prettiness! Where! Where! …”

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother by Max Gertler (1924)

This was the final portrait Gertler’s mother. In this work there is no hint of sentimentality or the personality which came to the fore in his earlier portraits of her. It is a depiction of dominance and authority. The art critics of the time highly praised it. Gertler loved the finished portrait and whether he was concerned that it would be bought and taken from him, it made him put a price of £200 on it in the hope that this would put off buyers. It didn’t work as it was bought for the full asking price, which was the highest price any of his works fetched during his lifetime !

Portrait of the Artist’s Family, a Playful Scene by Mark Gertler (1911)

Gertler completed many more paintings of his family. One such was his Portrait of the Artist’s Family, a Playful Scene which he completed in 1911. It depicts a room in the family’s Spital Square house with his two brothers Harry and Jack watching their sister tickling their mother who has fallen asleep in her chair.

Still Life with Bowl, Spoon and Apples by Mark Gertler (1913)

Mark Gertler, like many young artists, was interested in new art trends, some of which he may be able to experiment with. In November 1910 an influential exhibition opened at London’s Grafton Rooms entitled Manet and the Post-Impressionists curated by Roger Fry, which introduced the work of artists such as Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Picasso, to English art lovers. Despite some derogative remarks from well-known critics, Gertler found the exhibition amazing and began to experiment with brighter colours and flatter styles. In 1913 Gertler completed his painting, Still Life with Bowl, Spoon and Apples which displayed the influence of Cezanne

The Pond by Mark Gertler (1917)

The influence of Cézanne on his work, can also be seen in his 1917 work The Pond. In this depiction we see the branch of a tree extends like an arm pointing to the silvery pond which can be seen in the mid-distance, created from a patchwork of overlaid paint strokes. Gertler uses an abstract arrangement of colours to capture the lush greenness of this quiet spot, emulating the dappled effect of light and colour reflecting on the still surface of the pond. He has created a sense of depth in the way he has built up his painting with blocks of colour, which creates the impression of standing beneath the tree, overlooking the scene.

Garsington Manor and Gardens

The painting was completed by Gertler whilst he was staying at Garsington Manor, the Oxfordshire residence of renowned literary and artistic patron Lady Ottoline Morrell. It is believed that the painting, The Pond, was based on the fish pond at Garsington. At the outbreak of the First World War, Gertler was one of many artists and writers associated with the Bloomsbury Circle invited to Garsington Manor. Many were conscientious objectors who worked on the estate.

The Jewish Family by Mark Gertler (1913)

In 1912 Mark Gertler moved from the family home into the top-floor attic studio of 32 Elder Street, Spitalfields, which he shared with his brother Harry and Harry’s wife, and was just around the corner from the family home. Gertler remained deeply attached to home, family and the vital Jewish culture of his native Spitalfields/Whitechapel area of London’s East End, and this can be seen in his 1913 painting The Jewish Family. It was a depiction of a family of four of differing generations and could well be based on his own family members. The painting was bought by Edward Marsh, a scholar and influential art collector, who became a patron of Gertler. Sir Edward Marsh through the Contemporary Art Society bequeathed the painting to the Tate, London in 1954.

Around this time Mark Gertler became good friends with the writer Gilbert Cannan who based the title character of his 1916 novel Mendel, A Story of Youth, directly on intimate conversations he had with Gertler who talked about his early life and his relationship with C. R. W. Nevinson and Carrington. “Mendel” being the Yiddish given name of Gertler.

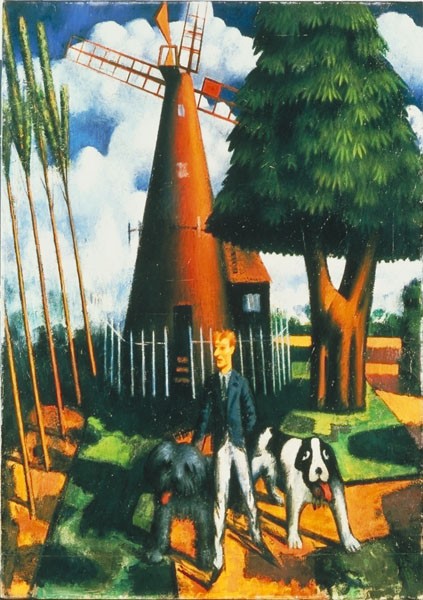

Gilbert Cannan at his Mill by Mark Gertler (1916)

Mark Gertler’s friendship with Gilbert Cannan flourished and in 1914 he went to stay with the writer and his wife, Mary, in their Hertfordshire home, a converted windmill, at Cholesbury. Cannan had been employed as a secretary by J. M. Barrie, the Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. A relationship developed in 1909 between Cannan and Barrie’s wife Mary Ansell, a former actress, who felt ignored by her husband. Although attempts were made by her husband to save their marriage they were divorced and she and Cannan were married in 1910. Mark became a regular visitor at Cannan and Mary’s windmill house and it is thought that he began making preliminary sketches during his early visits and completed his painting Gilbert Cannan at his Mill in 1916. It depicts Cannan with his dogs, Luath and Sammy. Cannan’s wife Mary owned Luath, and he had been the model for Nana, the Newfoundland dog in Peter Pan. Sadly the relationship of Cannan and Gertler declined after 1916, mainly because of Cannan’s increasingly unstable behaviour.

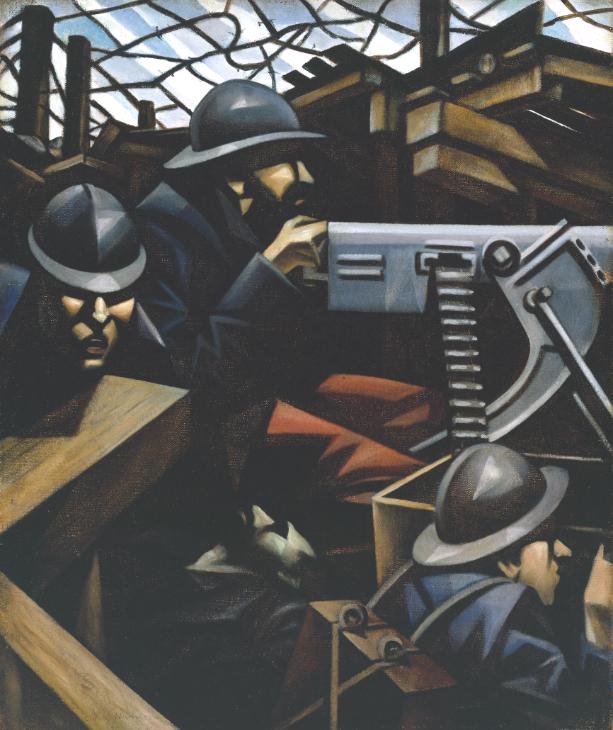

Merry-go-Round by Mark Gertler (1916)

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 there was a call to arms and Max applied for military service but was rejected on the grounds of his ‘Austrian’ parentage. In 1918 he again applied but was then later, after being called up in 1918, excused active service on the grounds of ill health which fortunately for Max avoided being forced to publicly declare his pacifist convictions, which were instead pictorially articulated in his 1916 anti-war painting entitled Merry-Go-Round.. Is this simply a painting of a carousel and people enjoying themselves or is there something more we should get from the depiction. The Painting is part of the Tate Britain’s collection and was begun in May 1916 when Gertler wrote to Lytton Strachey about it:

“… ‘I am working very hard on a large and very unsaleable picture of “Merry-Go-Round…”‘

Max completed it the following autumn. Merry-Go-Round depicts men in uniform with their girlfriends close by their side. Maybe it was the last time they had to enjoy life before they were sent to Europe to fight for King and Country. But all is not well as the facial expression on the men is not one of joyfulness that such rides would inspire. The faces are fixed in what looks like a cry for help. Like the ride itself, which is unstoppable, probably too is their fate on the fields of war. When it was exhibited, it was looked upon by many critics as one of the most important war painting. The writer, D. H. Lawrence, wrote to Gertler:

“…I have just seen your terrible and dreadful picture Merry-go-round. This is the first picture you have painted: it is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great and true. But it is horrible and terrifying. If they tell you it is obscene, they will say truly. You have made a real and ultimate revelation. I think this picture is your arrival…”

In an interview in 2021, Jeannette Gertler, Mark’s niece talked about the Merry-go-Round painting and she told the interviewer:

“…It was very controversial, not popular. People were annoyed about it and it was slated so much because it was making fun of the war. Making fun of the soldiers going around and around, achieving nothing. They thought it was very naughty of him to do that. Dispiriting. But he was opening their eyes. Really he was…”

On being asked what the Gertler’s family made of the painting Jeannette said:

“…They didn’t mind, Mark was their golden boy, their star, but other people were very annoyed about him making fun of the war. The boys were all pacifists you see. The family, they’d had enough trauma, as Jewish émigrés you know…”

Queen of Sheba by Mark Gertler (1922)

In 1920, Gertler was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was forced to enter a sanatorium. He would have to attend these medical facilities on a number of occasions during the 1920s and 1930s. These health issues created an unsettling period for Gertler but he decided to go to Paris and returned home full of ideas.

Mandolinist by Mark Gertler (1934)

He was inspired by the great French painter Renoir, who was a leading painter in the development of the Impressionist style. Gertler especially liked Renoir’s figurative paintings and on returning to London he began to focus on female portraits and nudes, and would sometimes combine figures with elaborate, colourful still lifes. The 1920’s was to become his commercially most successful decade.

The Violist by Mark Gertler (1912)

Two of Gertler’s preliminary Studies for The Violinist (1912)

Continuing with musical depictions I come to Gertler’s famous 1912 figurative painting entitled The Violinist but, referred to in a letter by Gertler, as The Musical Girl, which he started whilst attending the Slade Art School. He created preliminary pencil head sketches before he completed two oil on panel versions of The Violinist. The completed painting shown above is the second version. We do not know the name of the sitter but we do know she was a music student and a friend of Gertler’s family. Gertler was obviously taken by her distinctive looks with her striking, crop-haired, grey-eyed female who obviously captured his imagination. His sitter wears a loose, open-necked, vivid purple blouse. The vibrant colours of her clothing and background are perfectly balanced against the luminous skin tones. It is not the clothes we focus on but her face and her downward-looking eyes with their delicate lids relating closely to the earlier pencil study for the work. The painting was sold for GBP 542,000, the most paid for a Gertler painting. The top preliminary study sold for GDP 62,500.

Talmadic Discussion by Mark Gertler

It was around 1925 that Mark Gertler met Marjorie Greatorex Hodgkinson who had begun studying at the Slade under Henry Tonks in 1921. That same year Gertler was admitted to Mundesley Sanatorium in Norfolk, and Marjorie’s visits to him and her caring nature seemed to boost his health. He and Marjorie married in 1930 and their son Luke was born two years later.

Sales of Gertler’s paintings declined during the 1930s but despite their poverty, the Gertlers maintained a busy social life while Mark’s work continued with the still lifes, portraits and monumental nudes such as the Mandolinist. Sadly, Gertler suffered from long bouts of depression, and other forms of ill-health. Max’s marriage to Marjorie suffered because of his poor physical and mental health and by the mid-1930s, despite his efforts to improve matters, the marriage had deteriorated and Gertler’s mental health worsened and he became suicidal.

The Basket of Fruit by Mark Gertler

His mental decline was also part caused by the death of his close friends; the writers Katherine Mansfield in 1923 and D. H. Lawrence to tuberculosis in 1930. Mark’s friend, and once a fellow student of his at the Slade, Dora Carrington, committed suicide in 1932, two months after her close friend, Lyllton Strachey’s death. That same year Mark Gertler’s mother died. Gertler went on painting trips to Europe to help his moods but this didn’t work and to make things worse many art critics began to slate his work.

Self portrait with Fishing Cap by Mark Gertler

Gertler’s final exhibition, held at the Lefévre Gallery in May 1939, failed to attract visitors and he sold only three works. Not long after, on June 23rd 1939, Mark Gertler gassed himself in his Highgate studio. He was buried four days later in Willesden United Synagogue Cemetery.

Once again information for this blog came from ma ny Wikipedia sites but also from these excellent websites: