Anton Chekhov, the writer and physician, was born in January 1860. He was the third of six children and was brought up in the coastal town of Taganrog which lay on the north shore of the Sea of Azov in southern Russia. In 1876, when he was sixteen years old his father, Pavel, was in the process of building a new house but ran out of money and was mired in a huge debt. Rather than face the prospect of languishing in a debtors prison he escaped the town and moved to Moscow where his elder sons, Alexander and Nikolai were studying. Alexander was attending Moscow University and Nikolai was an art student at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Anton Chekhov remained behind in Taganrog to finish his studies at the local secondary school and was also charged with the task of selling the family’s possessions. It was not until three years later in 1879 that Anton Chekhov joined the family in Moscow.

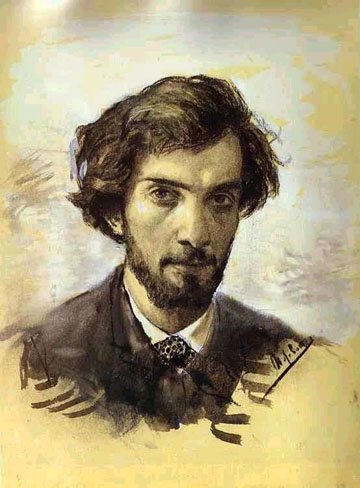

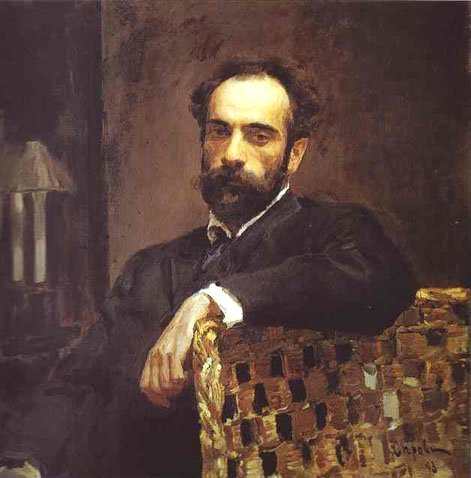

Anton Chekhov enrolled at the Moscow State Medical University and it was shortly after arriving in Moscow that he was introduced to Isaac Levitan by his brother Nikolai who was a fellow student of Levitan at the Moscow School of Painting. Anton Chekhov was just eight months older than Levitan and the close friendship between the two great men of the Russian Arts steadily grew and it would last until the end of their lives. This was a coming together of two Masters of Russian literature and the visual arts, and this close camaraderie led to a close style in the way the two considered and dealt with artistic challenges, so much so that their names are often quoted side by side both in specialized literature and popular writings.

Levitan completed a beautiful but small landscape painting, The Watermill, Sunset. It measured just 33cms x 52cms. He painted this work in the summer of 1880 when he was spending time in the small riverside town of Plyos on the banks of the mighty Volga River. Levitan loved the area and this period could be looked upon as one of the happiest times of his life. His friend Anton Chekhov said that when his artist friend and he were in Plyos he could detect a smile on Isaac’s face. Sadly, because of family tragedies and his unending fight against poverty, Levitan rarely smiled and was often the victim of melancholia.

Isaac Levitan had developed a great love of nature which almost certainly originated from his time at the Moscow School of Painting and the time he spent with one of his tutors, the Russian landscape painter, Alexei Savrasov. Savrasov was one of the most eminent of all 19th century Russian landscape artists and was renowned for his lyrical style and melancholic works of art. He was looked upon as the creator of the lyrical landscape style.

In all, Levitan painted this view three times. The first, which we see above, is housed in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and the other two, which were painted later, form part of two private Russian collections. The scene is set at sunset and the mill is in shadow whilst the forest, on the opposite side of the river in the background is bathed in evening sunlight. The light slants in from the right illuminating the far bank. It is the ending of the day and although the blue skies suggest otherwise, the location will soon be cast in darkness. In the foreground, the focal point is the wooden mill and the small rickety bridge which crosses over the small waterfall, the water of which powers the mill. In many of Levitan’s paintings he depicts small bridges crossing over water along with jetties which often had boats moored to them.

Levitan’s moody landscapes and the artists and poets who had influenced this style of art were commented upon by Alexandre Benois in his 1916 book, The Russian School of Painting. He wrote:

“…He brought to a summation that which Vasiliev, Savrasov and Polenov had foretold. Levitan discovered the peculiar charm of Russian landscape “moods”; he found a distinctive style to Russian landscape art which would have been distinguished illustrations to the poetry of Pushkin, Koltzov, Gogol, Turgenyev and Tyutchev. He rendered the inexplicable charm of our humble poverty, the shoreless breadth of our virginal expanses, the festal sadness of the Russian autumn, and the enigmatic call of the Russian spring. There are no human beings in his paintings, but they are permeated with a deep emotion which floods the human heart…”

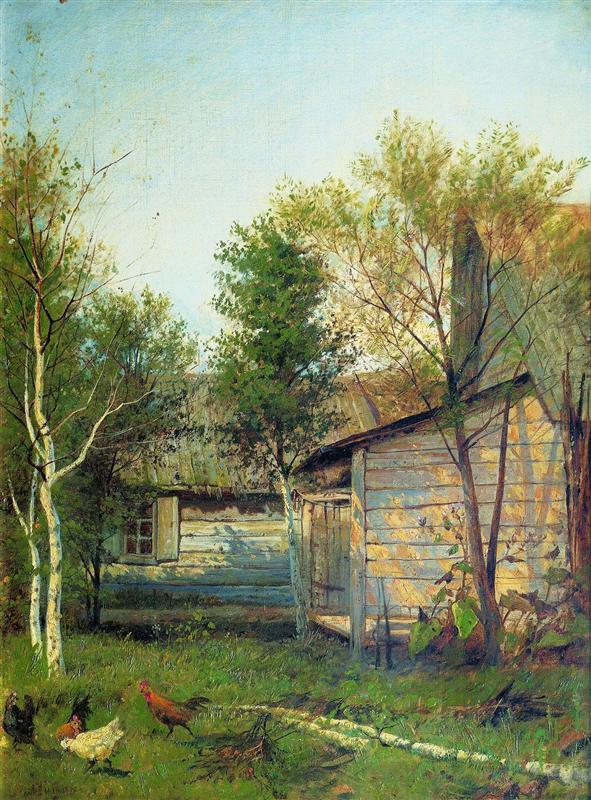

To supplement his income Levitan gave private painting lessons and he collaborated with the Chekhov brothers on the illustrated magazine “Moscow”. Levitan also spent time spent time on the popular Russian magazines, “Raduga” (Rainbow) in1883) and “Volna” (Wave) in 1884, where he worked on graphics and lithographs for the publications. He also collaborated with illustrations for Mikhail Fabritsius’ guide book, The Kremlin in Moscow. During the summers of the mid and late 1880’s Levitan spent much of his time with the Chekhov family, who had a summer residence on the Babkino estate close to the banks of the Istra River. The estate was owned by Alexsei Kiselev and he and his wife Marila would entertain artists and writers at their many soirees. Levitan eventually moved into the Chekhovs home and set up his own studio. One painting he completed in 1886, whilst staying with the Chekhovs was The Istra River.

His impoverished upbringing during which he often had no idea where or when his next meal would come from combined with the stress of being an artist trying to eke out a living had affected his health and he was diagnosed as having a degenerative heart disease and advised to move to a warmer climate further to the south of the country and so in late March 1886 Isaac Levitan visited the Crimea for the first time. It was here that he completed more than sixty sketches and paintings during his two months sojourn including one entitled In the Crimean Mountains which depicted an area around the town of Feodosiya, in eastern Crimea. It is a painting which manages to capture the bright sun and the intense heat of the mountainous setting. Levitan exhibited all the sketches he had completed whilst staying in the Crimea at the Moscow Society of Art Lovers (MSAL). All were purchased and with that success came financial stability for Isaac Levitan.

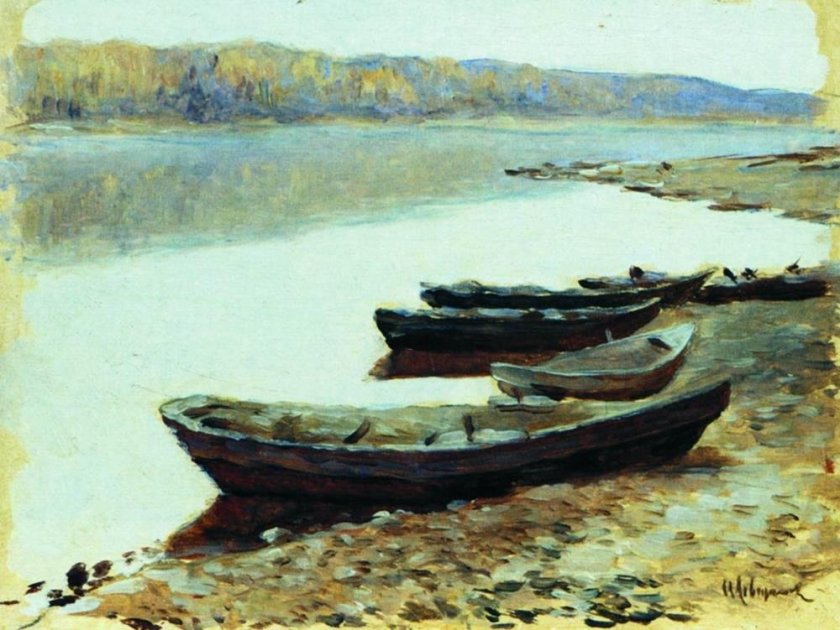

Between 1887 and 1890 Levitan would travel far and wide spending the long summer months in small towns along the Volga River, such as Plës (Plyos) and Vasil’sursk and two of his paintings of that time, Evening on the Volga (1888) and Evening: The Golden Plyos (1889) depicted the beauty of the river and the townships, which were situated on the banks of the great waterway, during the hours of sunset.

Levitan painted the Volga River scenes in various weather and light conditions and by doing so was able to convey associated moods. The Volga series established Levitan as the painter of the landscape of mood and his style became popular with other Moscow landscape artists of the time.

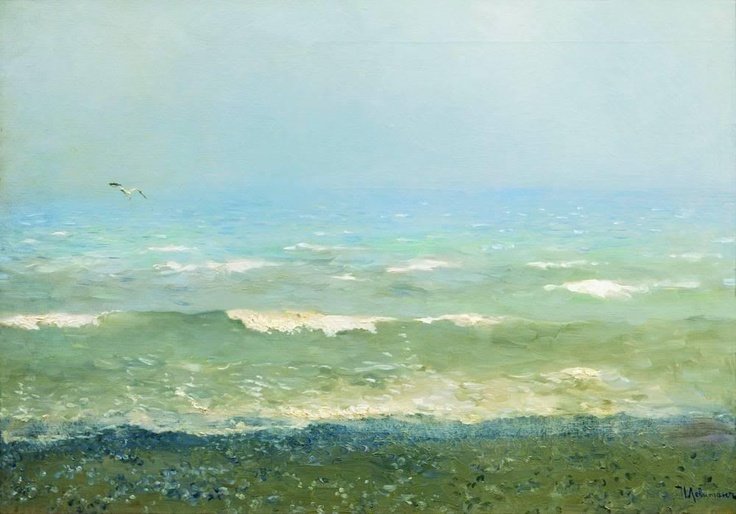

Levitan realised that much could be learnt from European artists and so, in March 1890, he embarked on a tour visiting Berlin and Paris and the Cote d’Azur towns of Nice and Menton. From his visit to the south of France, he completed a work entitled The Mediterranean Coast which is a truly beautiful depiction of the multi-coloured sea and the pebbled shoreline. He went on to Italy and visited Venice and Florence, Germany and Switzerland. However Levitan was a true Russian and despite the lure of the artistic life in the European capitals he preferred to return to his homeland.

In March 1891 Isaac Levitan became a member of the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions, and by the end of the year, displayed ten of his paintings at a Moscow Society of Art Lovers (MSAL) exhibition. His exhibits met with unreserved acclaim from both his fellow artists and the public.

Another of Levitan’s works of art I really like was completed in 1890, ten years after The Watermill painting, and was entitled Quiet Abode, The Silent Monastery. The monastery in question is the Krivooserski Monastery which is close to the river town of Yuryevets, located at the confluence of the Unzha and the Volga Rivers, some 350 kilometres north east of Moscow. Levitan had visited the area in the summer of 1890. In the painting we see the monastery in the background nestled amongst the high trees with just the ornate cupolas peaking above the tree canopy. In the foreground we can see a curved rickety wooden-planked bridge which traverses the slow-flowing river. The surface of the river shimmers in the sunlight. Look how beautifully Levitan has depicted the reflection of the monastery and the trees in this still expanse of water.

Anton Chekhov was so impressed with his friend’s painting that he introduced it into his 1895 novel, Three Years, in which he had the heroine of the story, Yulia Sergeievna, visit an Easter Week art exhibition and stand in front of what he described as

“…a small landscape… In the foreground was a stream, over it a little wooden bridge...”

One of the most haunting works by Levitan was his painting entitled Above the Eternal Peace which he completed in 1894. The first thing that strikes you about this evocative work is it is the depiction of an endless landscape. In the background we have a beautiful depiction of threatening heavy grey clouds which are intermingled with fluffy white ones, all of which are reflected on to the still waters of the lake below. In the foreground, sitting isolated on a verdant promontory which juts into the lake, is a small church with its gleaming silver cupola. Behind the church is the graveyard. It is separated from the church by some birch trees which have been bent over by strong winds. The graveyard looks abandoned and is rather overgrown and some of the crosses have lean over from the constant force of a strong wind which raced unhindered across the exposed promontory. The picture was painted on the shore of Lake Udomlia in Tver province, 250 kilometres north of Moscow.

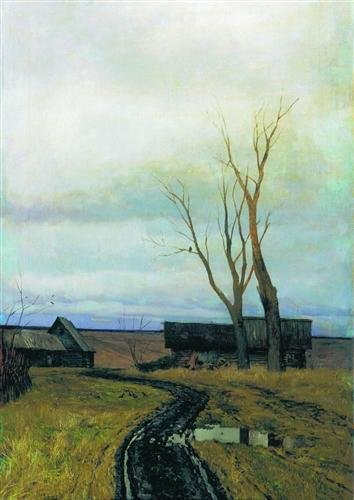

My final offering is another haunting work of art, not for its pictorial depiction but because where and what it is being depicted. It was a depiction of a well-trodden road which led convicts towards their penal colonies in Siberia. The painting is entitled The Vladimirka Road and Levitan completed it in 1892. The Vladimir Highway familiarly known as the Vladimirka was a 190-kilometre road which went from Moscow to Vladimir and Nizhny Novgorod, Siberia in the east. Siberia was at this time the customary place of exile, and this road depicted in the painting saw an endless movement of prisoners in shackles being marched from Moscow to the Siberian penal colonies. Levitan’s work of art is not just another landscape painting it is a combination of his realistic vision with a message. Before us is a somewhat desolate landscape but the point of the painting is to remind people, who look at the depiction, of the traumatic history of the road. It was about exile but it was not just about the exile of prisoners to Siberia. Levitan himself probably reflected on his own life at the time as in 1892 through to the beginning of 1893, by order of the Moscow governor-general, the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, about 20,000 Jews were deported from Moscow. Isaac Levitan was among those forced from his home and this expulsion because of his religion had traumatised him.

Everything about the painting reflects his troubled mind. Levitan has depicted the sky and the fields in dull and rather uninviting tones. Before us we have a flat and almost lifeless landscape with just the odd trees in the background. There is little or no vegetation and the path has been almost reduced to gravel due to the thousands of prisoners who had been marched along it over the years. Look at the colours he has used. Instead of bright greens and yellows he has gone for dull browns and lacklustre darker greens. The sky is grey with no hint of blue to uplift the painting. There is no sign of the sun which would have brightened the landscape but that was not the intention of the artist. There are no people depicted as he and many other realistic landscape artists believed the inclusion of people into a landscape painting detracted from the surroundings. Most of Levitan’s landscapes are without people. This work of art was termed a mood landscape in which the artist has transferred his mood into the way he depicts the scene. There is nothing uplifting about the view. There is nothing in the scene that would raise one’s spirits but that is just as Levitan wanted it to be. It was Levitan’s way of depicting hopelessness. It was the historical hopelessness of those who trudged their way to what would simply be slave labour. It was his own feeling of despair at his plight as a persecuted Jew.

To put a more uplifting spirit to this road the Bolsheviks, post-Russian Revolution, renamed it Shosse Entuziastov (“Enthusiasts’ Highway”) and many years later it became known as the Volga Motorway.

In March 1894 Levitan moved to the Tver Region, and later to Gorki. His health was deteriorating and by 1895 the degenerative heart disease which had been diagnosed ten years earlier was making life more difficult for Levitan. He was in constant pain and had little energy. His physical ailment triggered mental health issues in the form of depression and it was known that on a number of occasions he attempted to end his life. The only thing which gave him happiness was his love of nature. In 1897, he had become world-renowned as a landscape painter and he was elected to the Imperial Academy of Arts and in 1898 he was named the head of the Landscape Studio at his alma mater, the Moscow School of Painting.

Levitan spent the last year of his life at Chekhov’s home in the Crimea. Even though Levitan was aware that he was dying his last works were ones of brightness of colour. An example of this is one which remained unfinished at the time of his death in 1890. It was entitled The Lake although Levitan called it Rus’. It is believed that he labelled the work thus as he believed the painting reflect ed tranquillity and the eternal beauty of Russian nature and embodied all that was good about his homeland – its landscape, its people and its history.

In 1898 Levitan was given the title of academic of landscape painting. He still taught in the Moscow College of Art, Sculpture and Architecture. His paintings were constantly on display at Russia-wide exhibitions, at International exhibitions in Munich and the World Exhibition in Paris. He became internationally famous. His health started failing, his heart disease progressing quickly. He went abroad for some last-ditch medical treatment but any slight improvement was short lived. Isaac Levitan completed over a thousand paintings, during his short life. He died on 22 June 1900, just forty years of age. Levitan never married and had no children. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery at Dorogomilovo, Moscow. In April 1941 Levitan’s remains were moved to the Novodevichy Cemetery, close to the grave of his friend Anton Chekhov.

In August 2008 in the village of Eliseikovo, Petushinsky District near Vladimir – the Levitan House of Landscape was opened. Isaac Levitan first came to this area in May 1891, on invitation of the historian Vassily Kluchevsky, who had a summer home by the Peksha River. In 1892, Levitan returned, but on this occasion it was not from choice as it was the time when the Russian authorities banished Jews from Moscow. The great Russain opera singer and friend of Levitan, Fyodor Shalyapin, spoke of the art of his friend:

“…It has brought me to realization that the most important thing in art is this feeling, this spirit, this prophetic word that sets people’s hearts on fire. And this prophetic word can be expressed not only in speech and gesture but also in line and colour…”