Landscape and seascape painting must be the most popular art genre. Like all painting genres there are many good examples and some exceptional examples of such paintings. In today’s blog I want to highlight the exceptional landscape work of the nineteenth century Danish painter, Peder Mork Mønsted, who due to his naturalistic plein-air depictions, was considered the foremost landscape painter of his day in Denmark.

Mønsted was born on December 10th, 1859, a few years following the end of what was known as Den danske guldalder (The Danish Golden Age). This period of Danish history straddles the first half of the nineteenth century and is a period of outstanding creative production in Denmark. The start of the nineteenth century had been a disastrous period for Denmark and especially its capital, Copenhagen which had suffered from fires, bombardment and national bankruptcy, but it was also a period when the arts took on a new period of inspiration and originality brought on by the Romanticism movement of Germany, which was at its peak in the first half of the nineteenth century. It was a period when much of Copenhagen had to be rebuilt and this saw the development of Danish architecture in the Neoclassical style. The city took on a new look, with buildings designed by Christian Frederik Hansen and by Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll.

This Golden Age was most commonly associated with the Golden Age of Danish Painting from 1800 to around 1850 which included the work of Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (see My Daily Art Display five-part blog starting August 5th, 2016) and his students, such as Wilhelm Bendz, Christen Købke, Martinus Rørbye, Constantin Hansen and Wilhelm Marstrand. Eckersberg taught at the Academy in Copenhagen from 1818 to 1853, and became its director from 1827 to 1828. He was an important influence on the following generation, in which landscape painting came to the fore. He taught most of the leading artists of the period.

Peder Mork Mønsted was born near Grenå in eastern Denmark. He was the son of Otto Christian Mønsted, a prosperous ship-builder, and Thora Johanne Petrea Jorgensen. He had an elder brother, Niels. He was a pupil at the Crown Prince Ferdinand’s Drawing School in Aarhus where he studied under Andries Fritz, the Danish landscape and portrait painter. After leaving the Drawing School in 1875, Mønsted moved to Copenhagen and enrolled on a three-year art course at the Royal Academy of Art where he received tuition in many facets of art including the tutoring in figure painting by the Danish genre painter, Julius Exner. It was at the Academy that he began to learn about, and be influenced by, the art of Christen Købke and Pieter Christian Skovgaard, a romantic nationalist painter and one of the main figures associated with the Golden Age of Danish Painting. Skovgaard is particularly known for his large-scale depictions of the Danish landscape.

In 1878 Mønsted left the Academy to study under the artist Peder Severin Krøyer. Krøyer was one of the best known and the most colourful of the Skagen Painters, who were a community of Danish and Nordic artists living and painting in Skagen, Denmark. Krøyer was the unofficial leader of the group.

In his early twenties, Mønsted travelled extensively. In 1882 he journeyed through Switzerland and on to Italy where he visited the isle of Capri. During these journeys he would constantly sketch the people and the landscapes. One such painting to come from that Italian trip was completed in 1884 entitled In the Shadow of an Italian Pergola. Before returning to his home in Denmark he visited Paris and stayed there for four months during which time he studied at the studio of William-Adolphe Bougureau, the French academic painter.

Mønsted was a habitual traveller constantly seeking places and people to paint. In 1884, he first visited North Africa returning to Algeria in 1889. One of his later paintings, a portrait entitled The Smoking Moor, came from his time in North Africa.

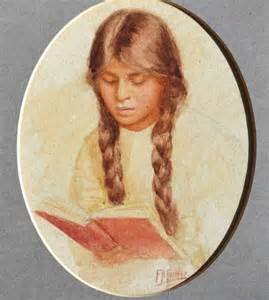

Peder Mønsted besides being an exceptional landscape painter was also a talented portraitist as we can see in his 1917 work, simply entitled Olga.

In 1885 his journeys took him to Sicily and Taormina, the commune in the Metropolitan City of Messina, which lies on the east coast of the island. It was from this visit that Mønsted completed his painting The Cloister, Taormina.

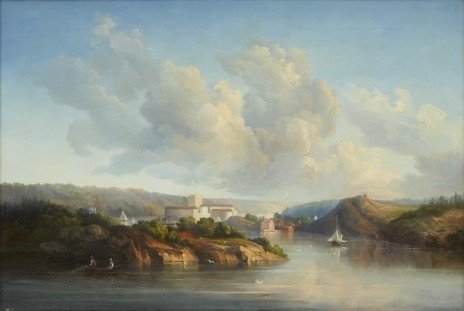

Mønsted visited Switzerland on several occasions and his 1887 painting Unloading Stone from a Barge at Ouchy recalled the time he visited the port of Ouchy which is situated south of the city of Lausanne, on the edge of Lake Léman.

On March 14th, 1889, at Frederiksberg, Peder Mork Mønsted married Elna Mathilde Marie Sommer. Nine years later the couple had a son, Tage.

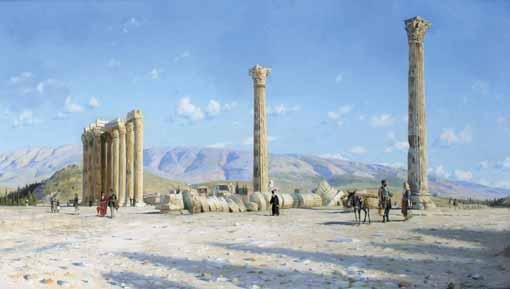

In 1892, Mønsted travelled to Greece, where he was a guest of King George I, who was Danish. While there, he completed portraits of the Royal Family including one of the king himself at the top of a ship’s gangway.

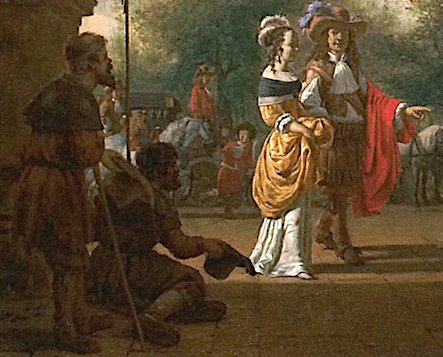

With his royal invitation to Greece, he also took the opportunity to depict the ancient sites. The above large-scale work (80 x 137cms) is one of his finest paintings of the last decade of the nineteenth century. It is thought that the two finely-dressed people depicted to the left in the mid-ground are King George I and his wife, Queen Olga of Greece. Further to the left are members of the famous Presidential Guard known as the Evzones. From Greece, Mønsted travelled to Egypt and Spain.

With his royal invitation to Greece, he also took the opportunity to depict the ancient sites. The above large-scale work (80 x 137cms) is one of his finest paintings of the last decade of the nineteenth century. It is thought that the two finely-dressed people depicted to the left in the mid-ground are King George I and his wife, Queen Olga of Greece. Further to the left are members of the famous Presidential Guard known as the Evzones. From Greece, Mønsted travelled to Egypt and Spain.

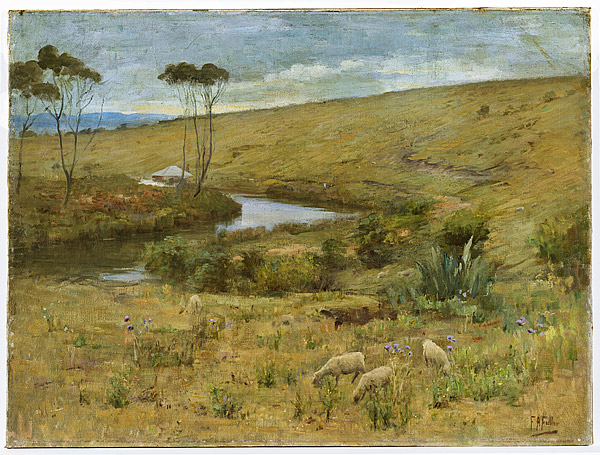

However, Peder Mork Mønsted will always be remembered for his beautiful landscape works often featuring his native countryside. It is hard to describe the works in a single word but if one had to then words like serene, placid, and tranquil come to mind. His depiction of water in the form of rivers and brooks and the surface reflections are breathtakingly beautiful. One good example of this is his painting Landscape with River.

Mønsted continued all his life to paint the Danish and Scandinavian landscapes and coastlines. His depictions of nature were poetic, even romantic. His forte as far as his landscape works are concerned is his discerning eye for the grandeur of nature and his unerring ability to record both detail and colour.

Of all the motifs within the landscape theme, water seems to be one that arouses the greatest admiration when depicted with serene beauty. It is in such landscape works that there is a multitude of conditions that challenge and stimulate an artist, whether they be beginners or the most experienced painters. It is known that many famous Impressionists had real problems when it came to the representation of water in their compositions and ended up with their depictions, concentrating much more on the effects 0f light on a scene rather than on a realistic representation.

The onset of World War I caused Mønsted to curtail his European travels but the 1920’s and 1930’s once again saw him journeying around the Mediterranean countries.

His travels produced numerous sketches that later became paintings which he presented at several international exhibitions. Most of his landscapes were, however, devoted to Scandinavia. He was especially popular in Germany, where he held several shows at the Glaspalast in Munich. During his later years, he spent a great deal of time in Switzerland and travelling throughout the Mediterranean. Most of his works are now held in private collections. In 1995, a major retrospective, called “Light of the North”, was held in Frankfurt am Main.

Philip Weilbach’s artistic icon, Weilbach Dansk Kunstnerleksikon often just referred to as Weilbach, is the largest biographical reference book of Danish artists and artists and the entry on Peder Mønsted sums up the work of this great man:

“…[Mønsted’s] great success was largely a consequence of his ability to develop a series of schematic types of landscape, which could each individually represent the quintessence of a Scandinavian, Italian, or most frequently Danish landscape. In motifs, built up around still water, trees, and forest, he specialised in portraying the sunlight between tree crowns and the network of trunks and branches of the underwood, the reflections on the water of forest and sky and snow-laden winter landscape paintings with sensations of spring, often all together in the same painting. Insofar as Mønsted included figures in his paintings, these were principally used as ornaments with a view to emphasising the idyllic character of the motif; and only rarely were the figures and the anecdotal element given as prominent a role as in traditional genre paintings…”

Peder Mork Mønsted died in his Danish homeland on June 20th 1941, aged 81.

![View of the Capitoline Hill with the Steps that go to the Church of Santa Maria] d’Aracoeli) by Paranesi (c.1757)](https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/view-of-the-capitoline-hill-with-the-steps-that-go-to-the-church-of-santa-maria-d_aracoeli-by-paranesi-c.jpg?w=840&h=632)