Paul César Helleu

At the end of my previous blog about the French artist Léon Bonnat, I talked about how he had bequeathed most of his art collection and the majority of his work to the local Bayonne museum and how the town named the Museum after him and yet it is now known as the Musée Bonnat-Helleu.. So who is “Helleu”?

Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne

The donation of Paulette Howard-Johnston, the youngest child of Paul and Alice Helleu made the museum one of the places of reference for the works of Paul César Helleu from 1988 onwards. It houses his works thanks to his daughter’s donation, as well as the donations and bequests of Paulette Howard-Johnston’s nieces, Éliane Orosdi and Ghislaine de Kermaingant, when in 2009, she died. In her will, the Bonnat Museum was designated as the heir to her collection of more than 300 new pieces. In 2011, the museum closed its doors for a major renovation, while thanks to this last bequest made by the Helleu family, the museum became the Musée Bonnat-Helleu.

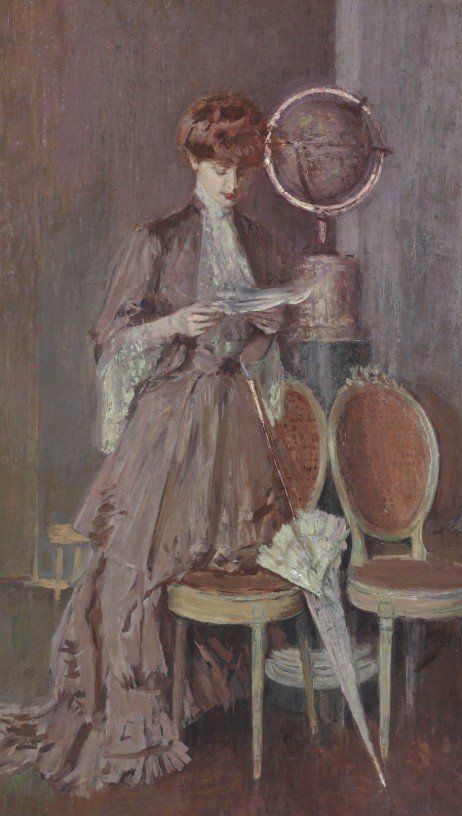

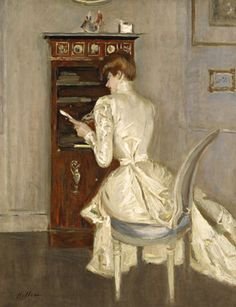

Portrait of Madame Helleu reading by Paul César Helleu

Paul César Helleu was born on December 11th, 1859, in the Brittany town of Vannes. His mother, Marie Esther Guiot and his father, César Helleu, who was a customs receiver, were married in 1855 and had two sons Paul and his elder brother Édouard. Paul took an interest in art when he was young. Following the death of his father when Paul was just a teenager, he decided he wanted to further his art studies by going to live in Paris. His widowed mother was against this idea but Paul persisted and travelled to Paris to continue his schooling at the Lycée Chantal. In 1876, at the age of sixteen Paul graduated and was admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts, at the atelier of Jean Leon Gerome, where he began his formal academic training in art.

The Saint Lazare Train Station by Paul César Helleu (1885)

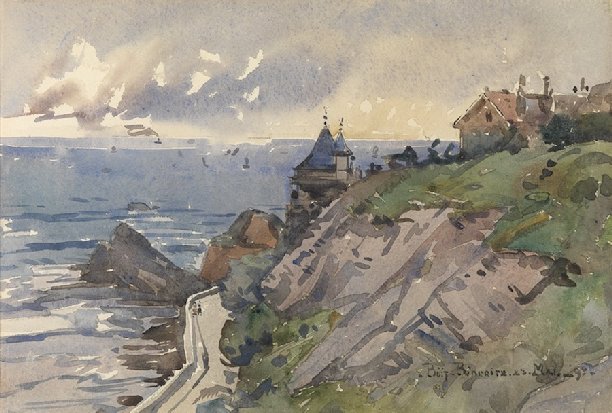

It was also in the Spring of 1876 that Helleu attended the Second Impressionist Exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. A total of nineteen artists participated in the exhibition, including prominent figures such as: Degas, Monet. Morisot and Gustave Caillebot. Whilst in Paris, Helleu made the acquaintance of John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler, and Claude Monet. He was struck by their modern, bold alla prima artistic technique, which was an approach to painting that involved applying layers of paint, also known as wet-on-wet, and completing a painting in a single sitting. This meant working with wet paint and not letting the layers dry, before applying the next layer. In Italian, the phrase alla prima translates to “at first attempt”. Helleu was also impressed with their plein air style of painting.

The Interior of the Abbey Church of Saint Denis by Paul César Helleu (c 1891)

Following graduation, Helleu found employment at the prestigious faience (earthenware) workshop, Joseph-Théodore Deck Ceramique Française. Joseph-Théodore Deck was a 19th-century French potter, and an important figure in late 19th-century art pottery. In 1856 he established his own earthenware workshop and began to experiment with styles from Islamic pottery, and particularly the Iznik style. At the time Paul César Helleu joined the workshop, Japonisme, the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858 was all the rage. Helleu created decorations for dishes.

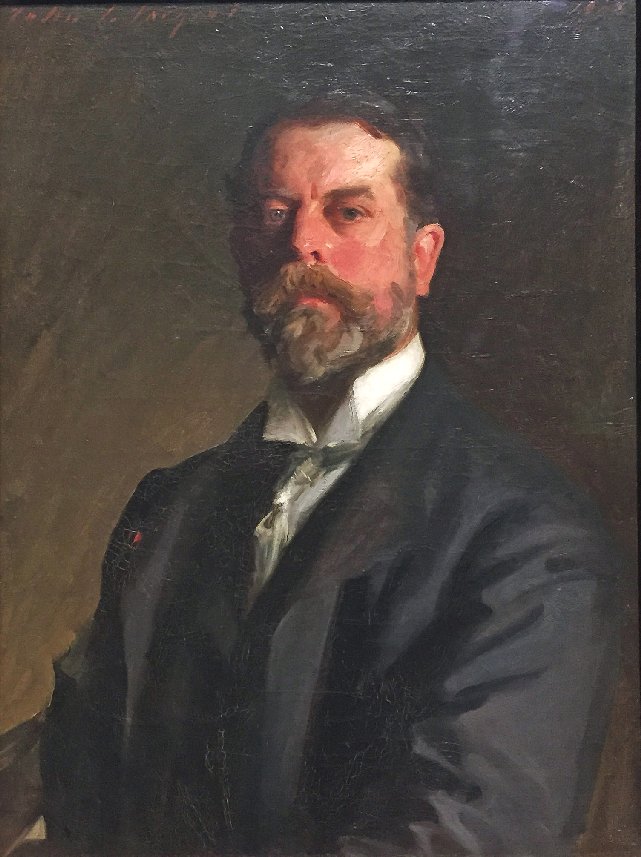

Giovanni Boldini self portrait (1892)

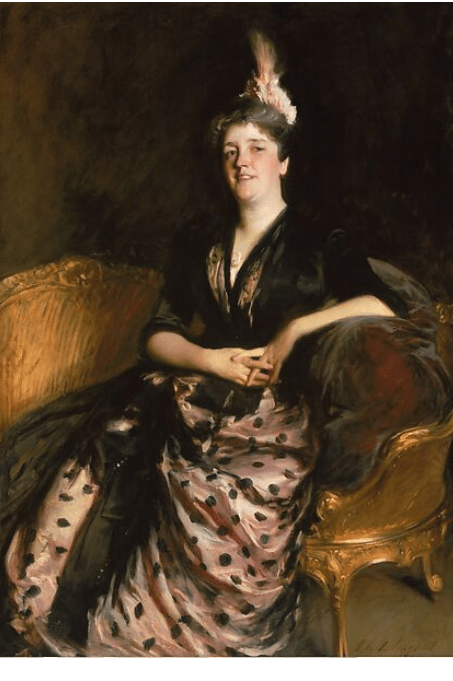

Portrait of Marthe de Florian, a French demi-mondaine and socialite, by Giovanni Boldini (1898)

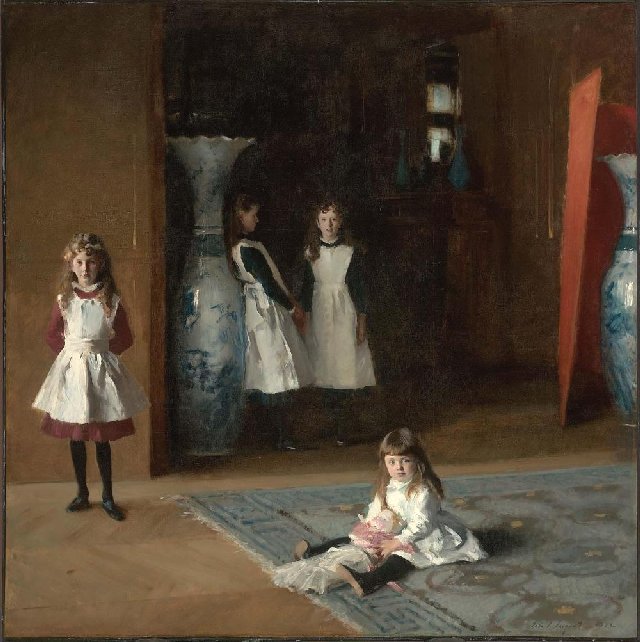

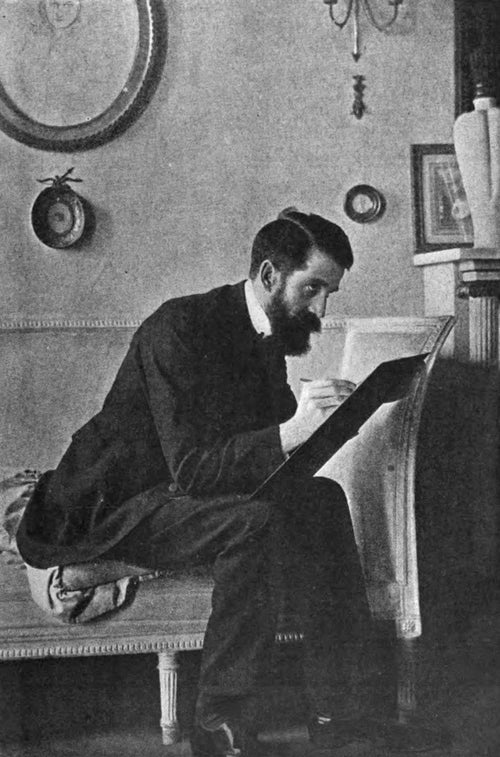

Around this time, Helleu met Giovanni Boldini, an Italian genre and portrait painter who lived and worked in Paris. His portraiture focused on all the grandes dames of Paris, and for them to have their portrait painted by Boldini was looked upon as the crowning event of the social season. Boldini became a friend and mentor to Helleu, and his style of painting had a great influence on his artwork. The other great influence for Helleu was his friendship with John Singer Sargent, often referred to as the leader of “posh portraiture” in Britain, that majorly encouraged Helleu. Helleu even sold his first painting to Sargent.

Portrait de Madame Chéruit by Paul César Helleu (1898) Madeleine Chéruit was a French fashion designer. She was among the foremost couturiers of her generation, and one of the first women to control a major French fashion house.

This time in Helleu’s life coincided with France’s Belle Époque era. The term, Belle Époque, literally means “Beautiful Age” and was a name given in France to the period between the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 up to to the start of World War I in 1914. During those forty plus years of peace, the living standards for the upper and middle classes increased, (albeit the lower classes did not benefit in the same way, or to anywhere near the same extent). It was the well-off who termed the phrase Belle Epoque labelling it a golden age in comparison to the humiliations that came with the Prussian invasion and what was to come, the devastation and occupation of the First World War.

Mademoiselle Vaughan by Paul César Helleu (1905)

It was a time of booming progress and prosperity in Europe, with Paris the centre of the fast-flowing changes in economics, technology, and the arts. However, as the name denotes, beauty was a key element of this prosperous period. The upper-class patrons would often commission artists to paint their portrait or one of a family member, in a luxurious and extravagant manner highlighting both their beauty and wealth. The finished portraits heightened an artist’s reputation, ensuring more clients for the artists.

Alice Helleu by Paul César Helleu (1885)

This blog is not only about Paul César Helleu but also his muse, lover, and later his wife, Alice Louis-Guérin. Helleu met Alice in 1884 when her mother asked him to paint a portrait of her fourteen-year-old daughter, Alice. At the age of twenty-four, Helleu appears to have fallen in love with her during this first meeting. Alice remained the artist’s favourite model throughout his life and she was also a muse for many other artists. Her beauty and sophistication also helped introduce her husband into the elite circle of artists, writers and society figures of the French capital. The Count de Montesquiou, who was a noted dandy and one of the leading figures in the artist’s group of friends, described her appearance as

“…La multiforme Alice, dont la rose chevelure illumine de son reflet tant de miroirs de cuivre…”

(‘The multifaceted Alice, whose rosy hair illuminates so many copper mirrors with its reflection.’)

Madame Helleu à son bureau by Paul César Helleu.

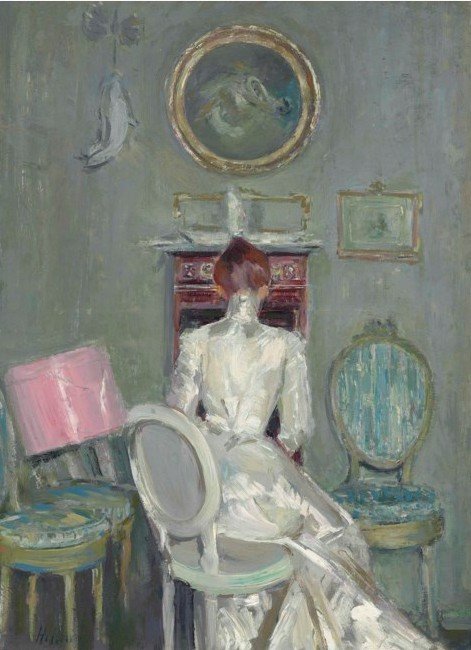

Helleu often avoided standard conventional rules of portrait composition, and would frequently depict his sitters from behind – standing before a mirror, or sitting at a desk, as was the case of his painting entitled Madame Helleu à son bureau. Note the porcelain koi carp hanging in the upper left corner which was an example of Japonisme which was all the rage in Paris at the time. The desk depicted in the painting and which appears in numerous works by Helleu is still in the artist’s family. The painting hanging above it is Boldini’s Leda and the Swan.

Madame Helleu assise à son bureau dans le salon de l’atelier de l’artiste, capturant une scène intérieure intime avec une élégance raffinée. (Madame Helleu seated at her desk in the artist’s studio salon, capturing an intimate interior scene with refined elegance.)

His painting entitled Mrs. Helleu sitting at her desk in the artist’s studio living room confirms Paul and Alice Helleu were had superb taste and these portraits depict Alice seated at a secrétaire in the couple’s drawing room of their Paris apartment, into which they moved in 1888. I suppose these two paintings cannot be considered as portraits in the conventional sense of the word, but rather as interior still life works, in which the furniture and surroundings are as vital as the sitter.

Madame Helleu by John Singer Sargent (1889)

Alice Guérin was depicted in a number of paintings by Paul Helleu’s friend John Singer Sargent.

Paul Helleu Sketching with his Wife by John Singer Sargent (1889)

In his 1889 painting, Paul Helleu Sketching with his Wife, Sargent depicts a tranquil outdoor scene, portraying the French artist Paul Helleu engaged in the act of sketching. Alongside him, sits his wife Alice who appears happy and relaxed. The figures of husband and wife are set against a lush, natural environment that suggests a calm and comforting ambiance. Sargent’s painting also manages to capture their fashionable clothing with Paul wearing a formal suit and Alice attired in an elegant dress. Both wear wide-brimmed hats that both provide shade and stylishly adorn their heads.

Portrait of Artist’s Wife by Paul César Helleu

Paul Helleu was one of Sargent’s closest friends. Initially, they had met in Paris in 1878. Paul was 18 years old and Sargent 22. Sargent’s artistic career had already taken off, and he was becoming known to the public as a great portraiture artist and was receiving many commissions for his work. However, on the other hand, Helleu was selling little of his work, and because of this, he was suffering from depression. Paul Helleu was financially strapped with hardly enough money to even eat and had to leave his studies in art due to lack of funds. Sargent, got to hear about the plight of his friend and visited him at his studio and although he never alluded to his friend’s dire financial difficulties, Sargent selected one of Helleu’s paintings, and commended it for its artistic merits. Helleu was so flattered that the successful Sargent would think so kindly of his work that he offered to give it to him. The story goes that Sargent responded to Helleu’s offer, saying:

“…I shall gladly accept, Helleu, but not as a gift. I sell my own pictures, and I know what they cost me by the time they are out of my hand. I should never enjoy this pastel if I hadn’t paid you a fair and honest price for it…”

He paid Helleu one thousand francs for the painting. Helleu never forgot Sargent’s generosity and moral support and later, when Sargent was suffering from depression after the death of his father, Paul and Alice Helleu went to stay with him in England.

Portrait of Madame Helleu by Paul César Helleu.

Paul César Helleu and Alice Louis-Guérin married, two years after their first encounter, on July 29th, 1886, at Neuilly sur Seine. She was two months away from her seventeenth birthday and Paul was twenty-six years old. They went on to have four children, Hélène in 1887, Jean in 1894, Alice in 1896 and Paulette in 1904.

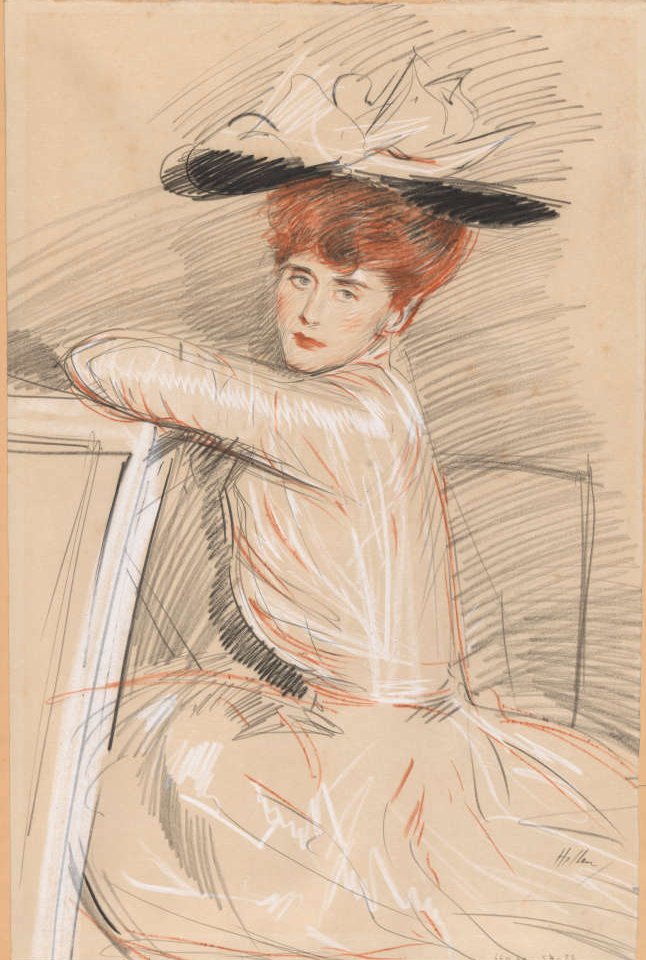

Details of Femme aux chapeau – Drypoint by Paul Helleu

Drypoint Portrait of a Young Woman wearing a Hat by Paul César Helleu (c.1900)

It is believed that during a trip to London in 1885 Helleu once again met Whistler who introduced him to James Tissot a French society painter, illustrator, and caricaturist who was living in the English capital. It was this established artist who taught Helleu the unique medium of etching. Helleu became fascinated by drypoint etching. Drypoint is a printing technique in which the printmaker scratches the lines on the printing plate with a sharp pointed tool. The printmaker holds the tool like a pencil and pushes the excess metal to either side of the furrow. It is this curl of rough metal, known as the ‘burr’, that gives the drypoint print its character. The ink is held in the burr as well as in the furrow and gives the edges of the printed line a soft, blurred quality. In Helleu’s work (above) the burr on the woman’s choker gives it a very velvety look. Over the course of his career, Helleu produced more than 2,000 drypoint prints and he quickly mastered this technique, using the same flair with his stylus as he demonstrated with pastels. It was the brilliance of his drypoint etchings that ensured Helleu’s place as one of the greats of the Belle Epoque, and he journeyed to Britain and America, and his artworks boosted his fame across both sides of the Atlantic.

Alice au chapeau noir by Paul César Helleu

Helleu and his wife had made many friends in Paris including Countess Greffulhe, a French socialite, known as a renowned beauty and queen of the salons of the Faubourg Saint-Germain which allowed Helleu to successfully expand his career as a portrait artist to elegant women in the highest ranks of Paris society

Paul Helleu’s yacht Étoile

Paul Helleu, wife Alice and baby daughter Paulette on L’Étoile (c.1904)

In 1904, Helleu was awarded the Légion d’honneur by the French president, Émile Loubet, and became one of the most celebrated artists of the Edwardian era in both Paris and London. He was an honorary member in important beaux-arts societies, including the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and the International Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, headed by Auguste Rodin.

New York City’s Grand Central Terminal.

During his second trip to the United States in 1912, Helleu was awarded the commission to design the ceiling decoration in New York City’s Grand Central Terminal. Helleu decided on a mural of a blue-green night sky covered by the starry signs of the zodiac that cross the Milky Way.

Paul César Helleu (1859-1927)

Helleu made his last trip to New York in 1920 for an exhibition of his work, but he realized that the Belle Époque era was over. He sadly realised that he had lost touch with that vibrant era. Shortly after his return to France, he destroyed nearly all of his copper plates. While planning for a new exhibition with Jean-Louis Forain, a French Impressionist painter and printmaker, Helleu died of peritonitis following surgery in Paris, on March 23rd, 1927 at age 67.

Information needed for this blog came from Wikipedia and Facebook plus the following websites: