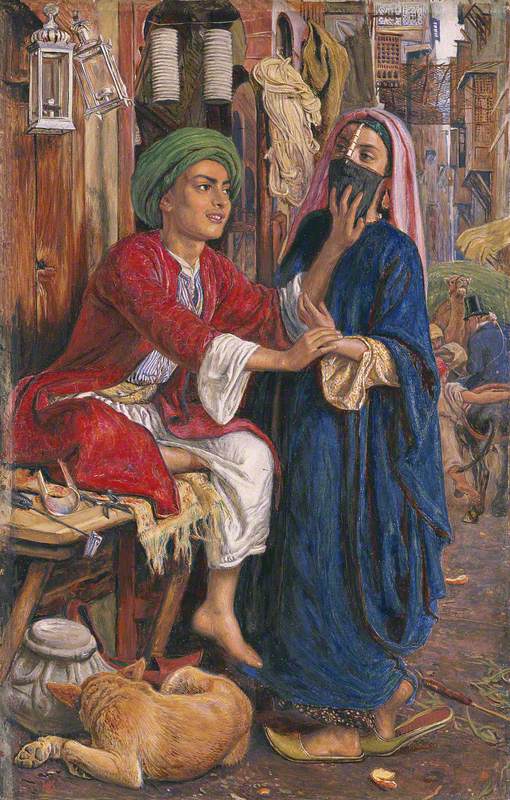

The setting for the Lantern Maker’s Courtship by William Holman Hunt is a street somewhere in the Middle East. We are outside a lantern maker’s shop. A variety of lantern hang from hooks in the wall behind the young lantern-maker and his equipment lies on the bench next to him. Beneath the bench, a dog lies curled up asleep. In the background we see a busy, narrow, with a man in a top hat and a blue jacket, riding a donkey away from us. A servant quickly follows the man and donkey. The man astride the donkey raises a whip at an oncoming local, who is leading a camel laden with goods, and the horrified local raises his arm to shield himself against the onslaught. The main characters of this painting are the young lantern-maker dressed in a long red coat and green turban, perched on a bench outside his workshop. Next to him stands a young girl dressed in a long blue gown and golden Turkish slippers. The lower part of her face is hidden by a black face mask. It is a happy coming together of the young couple. We see the smiling lantern maker reaching out to the girl. One of his hands gently touches her wrist whilst the other is outstretched feeling her face beneath the black mask. It is as if he is blind and wants to use his sense of touch to give him the vision of her face. Her face will be hidden from him until and if they become man and wife. Their happiness at the meeting is plain to see. He smiles broadly and her left foot curls up inside her slipper in a sign of ecstasy. Despite the painting’s informality, Holman Hunt’s devotion to detail can be seen in his portrayal of the drape and puff of the fabric, the careful depiction of the eastern-style shoes and dress, as well as the minutiae of the lantern maker’s tools and the finished and half-finished lanterns hanging nearby. The painting is awash with bright colours and the rich blue and vibrant red that leap from the canvas are characteristic of Holman Hunt’s artwork. By having this explosion of colour the street scene is magically brought to life.

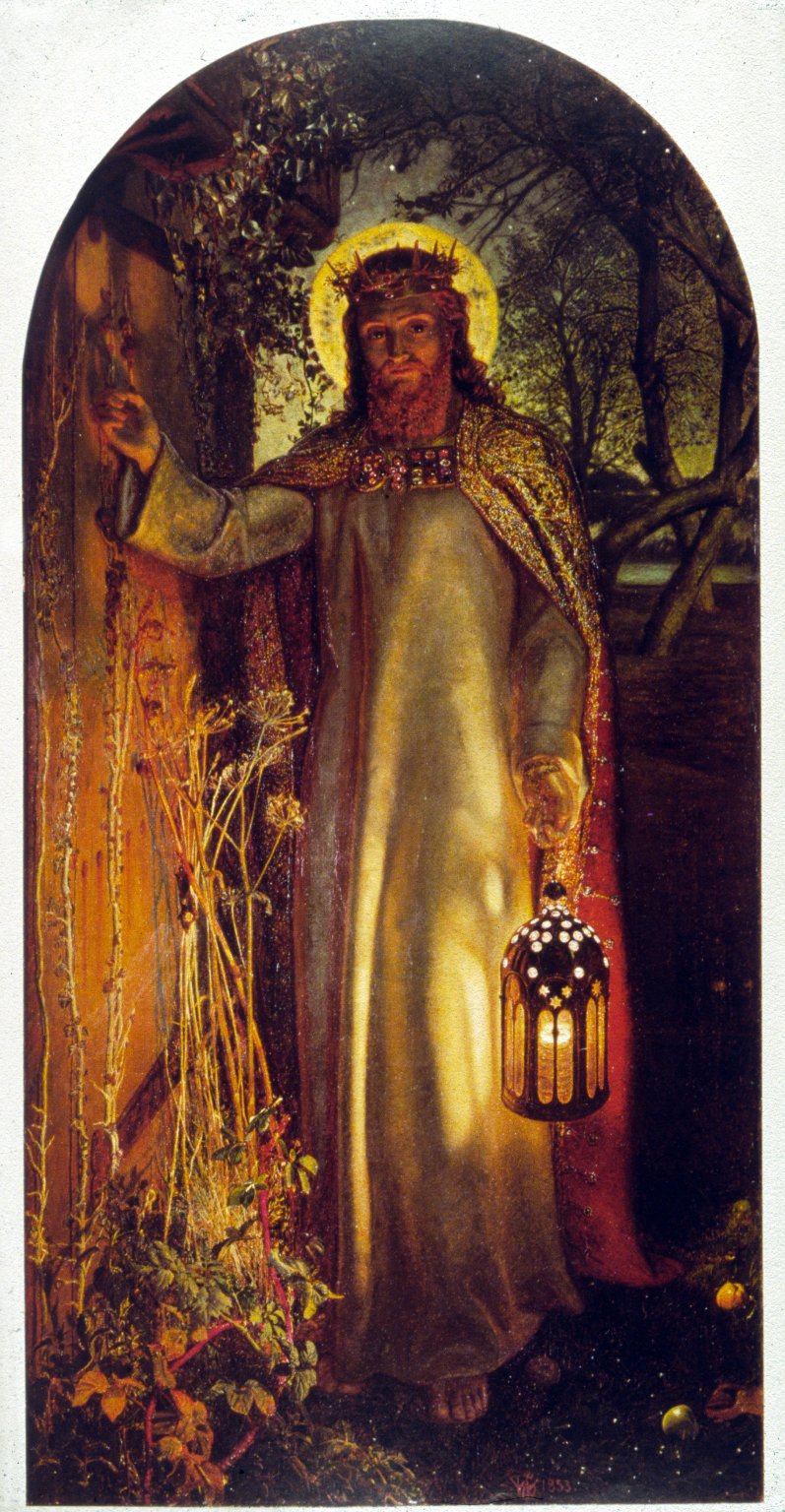

Another painting by William Holman Hunt on display at the gallery is his allegorical work entitled The Light of the World. It is thought that he started the work in 1850 but did not complete it until three years later. The painting depicts a Biblical scene, based on a passage from St John’s Gospel:

“…I am the Light of the World; he who follows Me will not walk in darkness, but will have the Light of life”.

Look at the way Hunt has depicted the door. It is very old and overgrown by ivy and brambles and there is no handle to use to open it. It was Hunt’s way of likening it to the problems of a closed mind. There are many ideas put forward as to where he painted the work. Some believe he painted it after dark in a hut on a Surrey farm; while others claim that his location was the Oxford University Press garden. Hunt’s original painting, which he completed in 1853, resides in Keble College Oxford. The one which can be seen at the Manchester Art Gallery is a smaller version of the original, which he worked on between 1851 and 1856. There is a third version which Holman Hunt completed around 1904, when he was eighty-three years of age. That version is to be found at St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

There is much symbolism within the painting which need considering and the St Paul’s Cathedral website offers their interpretation:

“…There are two lights shown in the picture. The lantern is the light of conscience and the light around the head of Christ is the light of salvation. The door represents the human soul, which cannot be opened from the outside. There is no handle on the door, and the rusty nails and hinges overgrown with ivy denote that the door has never been opened and that the figure of Christ is asking permission to enter. The morning star appears near Christ, the dawn of a new day, and the autumn weeds and fallen fruit represent the autumn of life. The writing beneath the picture, is taken from Revelation 3 .

“…Behold I stand at the door and knock. If any man hear my voice and open the door I will come in to him and will sup with him and he with me…”

The orchard of apple trees evokes several biblical references. The tree of knowledge in the garden of Eden was, according to legend, an apple tree and in some Christian traditions the wood of that tree was miraculously saved to construct the cross on which Christ was crucified. The fallen apples could symbolise the fall of man, original sin, and sometimes in Italian art can refer to redemption…”

As you look at Ford Madox Brown’s painting, Byron’s Dream, you try and work out what is happening and this fascinates me and it is why narrative paintings are high on my list of favourite painting genres. So let us just consider what we see. There is a young man and woman sitting on a hillside looking out over green fields and trees. The woman is dressed in a low cut, white blouse with lacy trim around the neck and cuffs and along with the blouse she wears a full length, red skirt. In her right hand she holds the pink ribbon of her wide-brimmed hat. The man is dressed in breeches, with a white shirt finished with ruffles under a black jacket. The woman stares out at a distant rider in the distance. The man, who is seated slightly behind her and hesitantly holding her hand, is not interested in what she is searching for but instead gazes lovingly at the woman’s face. Accompanying them on the hillside is a black and white dog which wears a wide gold collar. If we look at the midground we can just make out the subject of her gaze – a man on horseback below them, riding along the path towards them.

The painting is not just a depiction of any man and any woman but as the painting’s title, Byron’s Dream, indicates, it is a depiction of Lord Byron and his girlfriend. Not in reality but in Byron’s dream. Ford Madox Brown had been a great lover of Byron’s poetry, especially his 1816 poem entitled The Dream. The poem is described as conveying romantic beliefs about dreams. It also describes the view from the Misk Hills, close to Byron’s ancestral home in Newstead, Nottinghamshire, which we see in the painting.

Mary Chaworth, who was born at Annesley, not far from Mansfield, on the borders of Sherwood Forest, was a niece of Lord Byron. She was also the first woman Byron fell in love with, when he met her during a vacation at Southwell in 1803. They spent much time in one another’s company. The problem was he was yet a boy at fifteen, and she a woman at seventeen: The infatuation flowed entirely in one direction !!! He wrote many poems for her, but Mary didn’t care for the “lame, bashful, boy lord” and instead married John “Jack” Musters in August, 1805. The couple went on to have seven children. Mary separated from her husband on 10 April 1814 due to his infidelities and started writing to Byron. However, by that time, he was famous and was no longer interested in her. Mary is the “Maid” of the poem and it is she who is seen sitting with Byron in the painting.

The setting for William Holman Hunt’s painting, The Hireling Shepherd was in the Surrey countryside in Spring. Hunt and fellow artist and good friend, John Everett Millais, had travelled to Ewell in Surrey where they searched together for locations for painting. Eventually they discovered the ideal setting close to the River Hogswell. Millais worked on his painting Ophelia whilst Hunt selected the meadows near the fields of Ewell Court Farm to paint The Hireling Shepherd.

At first glance this is simply a depiction of a rural idyll and innocent young love but there is more to this painting than meets the eye. If we take Holman Hunt’s painting at face value, we see a ruddy-faced young shepherd kneeling on the ground. His small barrel of ale or cider is strapped to his belt. He reaches out wrapping his arm around the shoulders of a pretty young girl, dressed in peasant costume. On her lap is a small lamb and some half-eten apples. Although it is not known who the male was who modelled for Hunt, we do know that the red-headed girl was Emma Watkins, a local country girl who later travelled to London to model for Hunt so that he could complete the painting. Her later efforts to become an independent model in the capital city failed and she had to return home.

Now look more closely at the depiction to find some of the things you may have missed at first glance. In Hunt’s depiction, preferring to gain the attention of the young girl by showing her a death’s head hawkmoth he has captured, the shepherd has paid little attention to his flock of sheep who have crossed over a ditch and are now ensconced in a field next to an orchard. The sheep have been eating some of the fallen sour apples and are now becoming ill.

When the painting was first displayed in the Royal Academy, it was accompanied by a quotation from King Lear:

Sleepest or wakest thou, jolly shepherd?

Thy sheep be in the corn;

And for one blast of thy minikin mouth,

Thy sheep shall take no harm.

And yet there is still more to this painting. It is a work of symbolism. Holman Hunt explained it in a letter around the time the Manchester gallery had acquired it. Hunt wrote that he intended the couple to symbolise the pointless theological debates which occupied Christian churchmen while their “flock” went astray due to a lack of proper moral guidance.

The painting received mixed reviews. One anonymous reviewer wrote:

“…Like [Jonathan] Swift, [Hunt] revels in the repulsive. These rustics are of the coarsest breed, — ill favoured, ill fed, ill washed. Not to dwell on cutaneous and other minutiae, — they are literal transcripts of stout, sunburnt, out-of-door labourers. Their faces, bursting with a plethora of health, and a trifle too flushed and rubicund, suggest their over-attention to the beer or cyder (sic) keg on the boor’s back….Downright literal truth is followed out in every accessory; each sedge, moss, and weed – each sheep – each tree, pollard or pruned – each crop, beans or corn – is faithfully imitated. Summer heat pervades the atmosphere, — the grain is ripe, — the swifts skim about, — and the purple clouds cast purple shadows…”

And in the edition of the Illustrated London News the art critic objected to the “fiery red skin” and “wiry hair” of Hunt’s peasants. On the other hand, his supporters insisted that the painting was an unembellished and faithful image of society.

Notwithstanding what has been written about the work, I like it.

My final look at the works of the Pre-Raphaelites at the Manchester Art Gallery is one by Sir John Everett Millais, a work entitled Wandering Thoughts which he completed around 1855.

The woman is sitting back in a red upholstered chair with both of her hands resting on the carved wood of the padded arms of the chair. The background is dark and lacks detail and it contrasts with her pale skin. She is wearing a long black dress with lace-trimmed short sleeves which exposes her bare shoulders. A small posy of red flowers is fixed to the bodice. Her dark hair is neatly parted down the centre and secured away from the face. In her lap, we see a letter which must have fallen from her hand.

Her expression is one of contemplation. Her head is tilted forward and she looks down to the left. It is a blank expression, an unseeing countenance. The abandoned letter could well be the cause of her dour facial expression. What has she just read? Did the missive contain news which shocked her into dropping the letter? Is she now lost in thought as to what she has just read?

Questions, questions and more questions. I will leave you to come up with the answers.

In the next blog I will showcase some more of my favourite paintings on display at the gallery

…………………….to be concluded.