When we hear the word Impressionism we immediately think of French painters such as Monet, Renoir, Cassatt, Degas et al, but how much do we know about American Impressionists and their works? How did the Impressionism Movement become important for a time in America? To find the answer, we probably have to go back to the mid-nineteenth century as it was after the Civil War ended in 1865 that America developed a healthy economy and this was never more so than in the North where many of the victors, who had made their fortunes from the war, had become extremely wealthy. As is the case nowadays, it is often not just enough to be wealthy, one had to flaunt one’s wealth. The newly wealthy Americans wanted not just to be recognised as rich, they also craved to be looked upon as sophisticated which didn’t automatically go hand-in-hand with wealth. So the rich Americans sat in their large magnificent houses and realised that it wasn’t enough to just have a large building, they realised that what they filled their homes with could help in their quest for sophistication and what could be more sophisticated than having their house filled with European art and furnishings. American artists soon realised that European style art was a saleable commodity and many crossed the Atlantic to Europe, especially Paris, to study the latest artistic techniques.

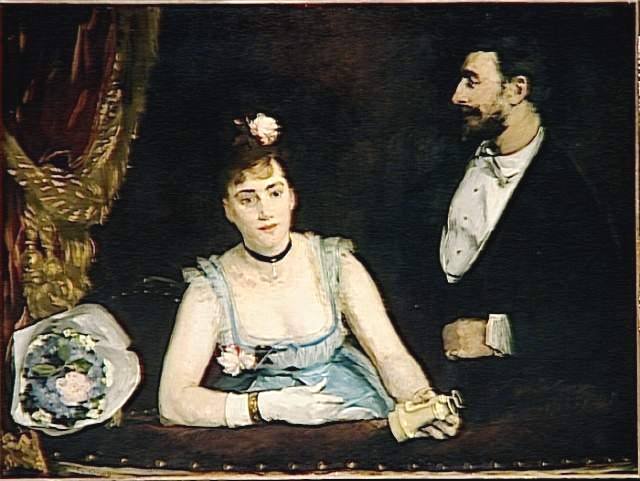

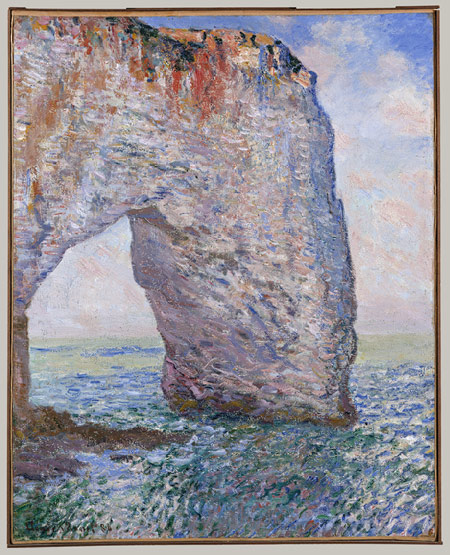

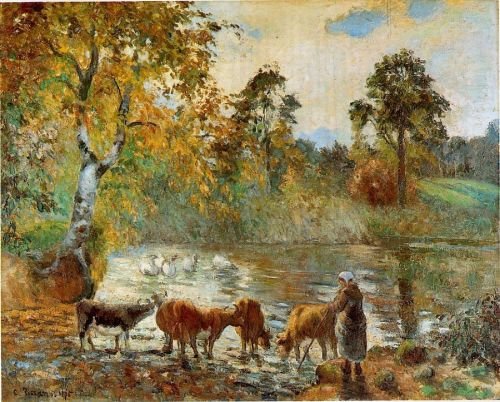

It was also around this time in Paris that French Impressionism was born. Impressionist art was a style in which the artist captured the image of an object as someone would see it if they just caught a glimpse of it. Their paintings were full of colour and, in the main, the paintings depicted outdoor scenes. There was a wonderful brightness and vibrancy about the works of the Impressionists. The images we saw on their canvases were without detail but were painted in bold colours. In the 1870’s there were already two American painters who had been seduced by the Impressionist style of art and were considered great exponents of this style. They were Mary Cassatt and the Italian-born son of American ex-patriots, John Singer Sargent.

During the mid-1880s, French Impressionist art became very popular with American collectors who began to appreciate this new style, and more American artists realised that they had to take on board this new phenomenon. Soon, exhibitions of Impressionist works were held in American cities and the paintings sold well.

Today I am going to look at a work of a less well known Impressionist, the American painter, John Henry Twachtman. John Twachtman was born in Cincinnati in 1853. His parents, Frederick Twachtman and his mother Sophie Dröge were German immigrants who had arrived in the country in the late 1840’s. His father had many different jobs including being a policeman, a storekeeper and a cabinetmaker but his most lucrative work was as a window-shade decorator at the Breneman Brothers factory, and when his son, John, was fourteen years of age he joined his father in the business, as well as attending classes at the Ohio Mechanics Institute. John developed a love for art and persuaded his parents to allow him to enrol for a part-time course at the McMicken School of Design in Cincinnati and this is when he met and was mentored by an already successful American realist artist, Frank Duveneck who invited Twachtman to share his studio in Cincinnati.

In 1875, when he was twenty-four years of age, he and Duveneck, who was just five years his senior, travelled to Europe to study European art. First stop was Munich where Twachtman studied for two years at the city’s Royal Academy of Fine Art tutored by the German genre and landscape painter, Ludwig von Löfftz. This artistic establishment was a long-standing center of artistic excellence and was one which attracted increasing numbers of aspiring American artists. From there he, Duveneck and another American student attending the Academy, William Merritt Chase, travelled to Venice in the spring of 1877 and spent much of their time painting en plein air.

Twachtman returned to America in 1878 and for a brief time taught at the Women’s’ Art Association in Cincinnati. He also joined the Cincinnati Etching Club where he became friendly with Martha Scudder, a Cincinnati artist and daughter of a local physician. Martha had studied at the School of Design and also in Europe, and had, on a number of occasions, exhibited her work. In 1880, Twachtman married, Martha Scudder. Soon after she married she gave up her artistic career and simply devoted herself to bringing up her family. John and Martha had two children: a son, J. Alden Twachtman, who was born in March 1882 and went on to became a painter and architect and a daughter, Marjorie, who was born in Paris in 1884. In 1880 John and Martha left America on honeymoon and went to Europe and Bavaria where Twachtman helped out as an art teacher in Duveneck’s school. Twachtman tired of the Munich style’s painting especially its lack of draughtsmanship and so he upped roots and moved to Paris, where in 1883 he enrolled at the Académie Julian, where he studied under Gustave Boulanger, the French figure painter who was renowned for his classical and Orientalist subjects. Another of his tutors was the French figure painter, Jules-Joseph Lefebvre.

Twachtman returned to the United States in 1887 and remained there for the rest of his life settling in Connecticut where he established an informal art school at Holly House, a boarding house for artists at Cos Cob, a small fishing village near Greenwich. This became a magnet for young aspiring artists, who came and were taught by Twachtman. Ten years later in 1897, Twachtman along with Childe Hassan and J Alden Weir became founder members of a group known as the Ten American Painters generally known as The Ten. This group was considered to be a sort of Academy of American Impressionists who had broken away from the more conservative Society of American Artists. From 1899 onwards, although living on his farm in Greenwich, Twachtman spent most of his last summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts and it was here that he died suddenly of a brain aneurysm in 1902, aged 49.

The painting by John Twachtman, which I am featuring today, is one of his many winter landscapes. This one is entitled Winter Harmony and was completed by the artist in the last decade of the nineteenth century. It now hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The painting features a pool on the artist’s property and was to be depicted in a number of his works.