My Daily Art Display today is all about the artist and the person who is the subject of the painting. The artist who painted today’s featured painting was Mark Gertler and the painting which he completed in 1916 is entitled Gilbert Cannan and his Mill.

Marks Gertler was born in Spitalfields, London in 1891. He was the youngest of five children born to Jewish immigrants from Poland, Louis Gentler and Kate Berenbaum. He had two older brothers and two older sisters. At the age of one, his father took the family to his mother’s native city, Przemyśl in south-east Poland where they worked as innkeepers. The business failed and one night in 1893, in desperation, Gertler’s father Louis, without telling anyone, left them all and went off to America to search for work. He eventually sent word to his wife telling her that once he was settled she was to bring the children to live with him there. It never happened as all his hopes of making a fortune ended in failure. Louis Gertler returned to Britain, and had his family join him in London in 1896. It was at this time that his son’s Polish name “Markz” was changed to Mark.

From a very early age Mark Gertler showed a talent for drawing. His first formal artistic tuition came when he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic in London. Unfortunately because of the family’s dire financial circumstances he had to leave the course after just a year to try and earn some money as an apprentice with a stained glass maker. However he still maintained his art tuition, attending evening classes at the Polytechnic. In 1908 he entered a national art competition and was awarded third place. Buoyed up with that success, but knowing the cost of art training, he applied for a scholarship from the Jewish Education Aid Society. His application was successful and in 1908, aged seventeen, he enrolled on a three year course at the Slade School of Art. It was whilst on this course that he met Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer and Charles Nevinson, all of whom would be leading artists in the twentieth century. Whilst studying at the Slade, Gertler also met the aspiring painter Dora Carrington, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. Gertler fell in love with her and pursued her relentlessly for many years. The story of his brief love affair with Dora was featured in the 1995 biographical film Carrington. Unfortunately for Gertler his love was unrequited and at one point in this tempestuous relationship he threatened to commit suicide.

Gertler was fortunate enough , in these early days, to be patronized by Lady Ottoline Morrell, the English aristocrat and society hostess and it was through her that Gertler became acquainted with the Bloomsbury Group. He was also introduced to Walter Sickert, who at the time was the leader of the Camden Town Group. With all these new artistic and society connections it was not long before he was enjoying great success as a painter of society portraits. Unfortunately Gertler had a very abrasive manner and was extremely temperamental. This did not go down well with his clients and his popularity and that of his paintings waned sharply causing him some financial problems.

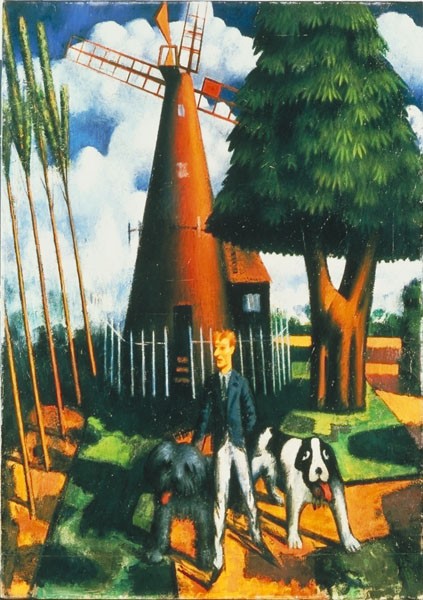

In 1914 Gertler visited the writer and the subject of today’s painting, Gilbert Cannan, who lived with his wife in their converted windmill at Cholesbury, Hertfordshire. They became great friends and over the next two years Gertler would be a regular visitor to the mill along with the likes of the writers Katherine Mansfield and D.H.Lawrence The latter would feature Gertler as the sculptor Loerke in his celebrated novel Women in Love. It was during one of his early visits that Gertler started his painting which he later entitled Gilbert Cannan and his Mill.

In 1920 when he was just twenty-nine years of age he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and this ailment resulted in many long stays in various sanatoriums. Around this time, when his artistic career was in decline, he taught part-time at Westminster School of Art. Gertler’s life began to unravel in the 1930’s. A war with Germany was brewing. His mother, whom he was very close to, had died. The once love of his life Dora Carrington had committed suicide in 1933. His exhibition at London’s Lefevre Gallery was ridiculed by the critics. In 1936, no doubt as a result of these personal and professional setbacks, he attempted to commit suicide but failed. Three years later, in 1939, aged forty-eight, he succeeded in ending his life by gassing himself at his studio in Hampstead.

The subject of today’s painting, as I have said was Gertler’s friend Gilbert Cannan. Cannan, a novelist, was born in Manchester in 1884 of Scottish ancestry. He was well educated studying at Manchester Grammar School and King’s College Cambridge. After receiving his university degree he went into the legal profession. This profession was not for him and after a brief dabble into the world of theatrics he turned all his efforts to writing. He worked as a secretary to the Scottish author and dramatist J M Barrie who created the famous character Peter Pan. Over time, Gilbert Cannan and Barrie’s wife Mary became lovers. James Barrie and his wife were divorced in 1909 and the following year Mary Barrie and Cannan were married.

In the years before the First World War Gilbert Cannan became friendly with the Bloomsbury Group, a group of writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists who, throughout the 20th century, held informal discussions in Bloomsbury, London,. The group would also congregate at Cannan’s home which from 1916 was a converted mill at Cholesbury in Hertfordshire and it was during this time that he met Dora Carrington and Mark Gertler. The mill we see in the painting was Cannan’s home and was a favourite place for his intellectual circle to meet.

The painting is a full-length portrait of Gilbert Cannan standing in front of the mill with his two dogs. The large black dog on the right hand side of Cannan is a Newfoundland dog called Luath. To the left hand side of Cannan is his large black and white St Bernard dog Porthos. Porthos was originally owned by J.M.Barrie and was used as a model for the dog Nana, dog which served as the Darling children’s nurse in J.M.Barrie’s famous book, Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up.

What is interesting and somewhat quirky about this painting is Gertler’s use of geometrical shapes such as cones and triangles. This can be seen in the shape of the windmill and the foliage of the large tree to the right of it. Even the way Cannan and his two dogs are portrayed has a triangular shape to it as does the way the tall poplar trees on the left of the work lean to the left against the side of the painting. This was a reflection of Gertler’s interest in the contemporary art which was popular at the time. The bright colours used by Gertler were not realistic and reflects the anti-naturalistic modern style of the era.

I think I am drawn to this painting purely for its eccentricity and nonconformity and the way Gertler has added vibrancy to the work with his use of unrealistic colouring. The painting can be seen at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and as I have said on a number of occasions you must add a visit to this wonderful establishment on your “to do” list.