Francis Danby was an English painter, born in 1793, in a small village near Waterford, Ireland, where his father owned a farm. When he was fourteen years of age his father died and he along with his mother and twin brother moved to Dublin. Whilst living in Dublin, Francis Danby enrolled at the Royal Dublin Society’s Schools of Drawing where he received artistic training. It was at this establishment that he met the renowned Irish landscape painter James Arthur O’Connor and it was through his mentorship that Danby developed a love of landscape painting. Danby also struck up a friendship with another fellow student, George Petrie, and they along with O’Connor left Dublin in 1813 and travelled to London. By all accounts the trip had not been well planned financially and their funds soon ran out and they had to head back to Ireland, on foot, but on the way they stopped off in Bristol. It was in this city that Danby managed to supplement his meagre worth by painting watercolours of the local scenes and selling them to the locals. At the same time as selling some of his work, he kept back what he considered to be his best paintings and sent them to various London exhibitions.

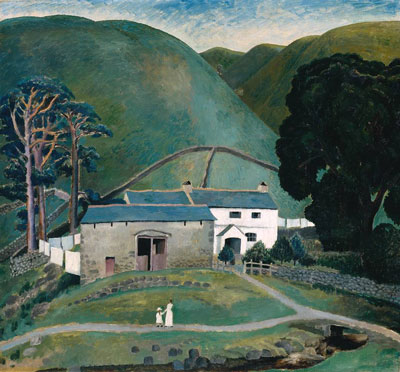

The works of Francis Danby, which were shown at various London sites, received favourable reviews and were soon in great demand. It was whilst still living in Bristol around 1818 that Danby joined an informal association of artists based around Bristol, which had been founded by the English genre painter, Edward Bird, known as the Bristol School or Bristol School of Artists. In 1821, Danby had a painting of his first exhibited at the Royal Academy. It was entitled Disappointed in Love and is My Daily Art Display’s featured work today. In 1824 Danby left Bristol and moved to London. It was around this time that Danby gave up his naturalistic and topographically accurate landscapes and moved towards poetic landscape painting. Poetic landscapes gave one the geography and architecture of landscapes from a subjective point of view, using elements of myth, fantasy or the picturesque. Claude Lorrain is usually looked upon as the originator of this style and this style of painting culminated in the Romantic landscape of the 19th century. A Poetic Landscape presents us with an imaginary place and for that reason the artists did not have to worry about topographical accuracy and it allowed them the opportunity to transform the characteristic features of, for example, Italian geography and architecture, and turn them into mythical or pastoral fantasy. This painting genre allowed artists to exaggerate the shape and height of mountains, delete or redesign buildings and objects, insert dramatically placed trees or human figures, and throw strongly contrasted lighting effects over it all. The public liked this style of landscape painting and did not care about the topographical veracity of what they saw. People, at the time, preferred this style to the topographical landscape with its dryly objective recording of what was actually there.

Another artistic genre Danby began to draw on was the large biblical scenes such as his 1825 painting The Delivery of Israel, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy and which led to him being elected an Associate Member of the Royal Academy. In the next two decades Francis Danby produced many large biblical and apocalyptic paintings which were to rival his contemporary and renowned “high priest” of apocalyptic art, John Martin.

Francis Darby, already an Associate Member of the Royal Academy was put up for election in 1829 to become a Royal Academician. When the votes were counted, he was devastated to find he had lost out by one vote to John Constable, who was elected instead of him. This year, 1829, was an annus horriblis for Danby as this was also the year that his marriage to his wife Hannah failed and he took himself a mistress. Hannah went off with another artist Paul Falconer Poole who had spent some time in the Danby household. London Society was scandalised by the goings-on at Danby’s household and in 1830 he went into self-imposed exile in Paris along with his mistress. From 1831 to 1836 Danby worked out of Geneva reverting back to his topographical watercolour landscape art work.

In 1837 he returned to Paris and a year later went back to living in London. It was in that year he produced his famous work, The Deluge, which re-established his reputation amongst the art community. This massive canvas, measuring 2.85m x 4.52m, depicted an area of harsh and violent weather and writhing, diminutive bodies trying to save themselves from the stormy waters. The painting put Danby briefly back in the limelight. However for Danby, life as an artist was becoming too much for him and in 1847, aged 54, he left London and went to live in Exmouth, Devon.

Whilst living in Devon Danby still found time to paint concentrating on landscapes and seascapes but he also took up boatbuilding. Francis Danby died in Exmouth, in 1861, aged 67. To the end of his life Danby constantly had money problems and was embittered that he never gained the recognition he deserved from the Royal Academy and was never elected as a Royal Academician. The final straw came two days before he died when he learnt that his ex-wife’s husband, Paul Falconer Poole had been elected a Royal Academician !

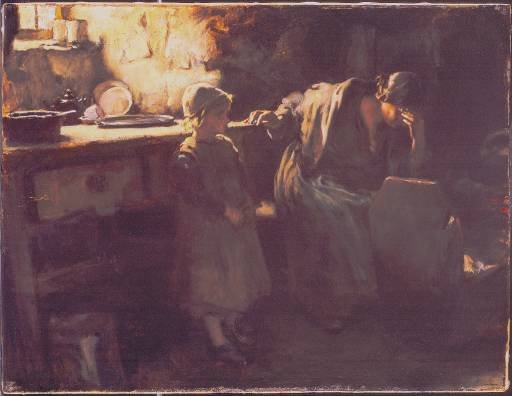

My Daily Art Display painting for today is by Francis Danby which he completed in 1821 and is entitled Disappointed Love. The painting was the first painting Francis Danby exhibited at the Royal Academy, and it became one of his best-known works. Before us, we see a heartbroken young woman who has just been jilted. Her hands cover her face as she sits weeping on the bank of a lily pond surrounded by dark and murky woodland. The occasional small white flowers, dotted around, struggle to lift the dark green and browns of the undergrowth. This gloomy undergrowth mirrors the depressed mind of the young girl. Her long dark tresses hang down over her white dress. On the ground beside her we see her discarded bonnet, her scarlet shawl , a miniature portrait of her lover and other letters which she has not yet destroyed. Her sad figure dressed in white is reflected in the water and in some way it seems that the water is drawing her to it so that she can end her life and her misery, in an Ophelia-like fashion. Floating on the surface of the pond are pieces of a letter which she has torn up and discarded. Eric Adams wrote a biography in 1973 on Francis Danby entitled Francis Danby: varieties of poetic landscape and he believes the setting for the painting was on the banks of the River Frome on the outskirts of Bristol and that the model for the painting was a model at the Bristol Artists newly founded Life Academy. There was a lot of criticism of the painting, not so much for the poetical nature of the work but for its technical faults, in particular the lack of proportion of the plants in the foreground.

When the painting was put forward to the Royal Academy jurists to see if it should be allowed in to the 1821 Exhibition it was not wholly loved. An account of the jurist’s comments on seeing Danby’s painting was reported some twelve years later as:

“…An unknown artist about ten years ago sent a very badly painted picture for the exhibition. The committee laughed, but were struck by “something” in it and gave it admission. The subject was this. It was a queer-coloured landscape and a strange doldrum figure of a girl was seated on a bank, leaning over a dingy duck-weed pool. Over the stagnant smeary green, lay scattered the fragments of a letter she had torn to pieces, and she seemed considering whether to plump herself in upon it. Now in this case, the Academicians judged by the same feelings that influence the public. There was more “touching” invention in that than in the nine-tenth of the best pictures exhibited there the last we do not know how many years. The artist is now eminent…”

To my mind it is a beautiful painting, full of pathos, and one cannot but feel sympathy for the young girl. It was for this reason that I was surprised to read an anecdote about this painting and the depiction of the girl. Apparently the Prime Minister at the time, Lord Palmerston, was being shown the painting by its owner, the wealthy Yorkshire cloth manufacturer, John Sheepshanks and commented that although he was impressed by the deep gloom of the scene, it was a shame that the girl was so ugly. Sheepshanks replied:

“..Yes, one feels that the sooner she drowns herself the better…”

How unkind !

This painting along with the rest of his outstanding art collection was presented to the Victoria & Albert Museum