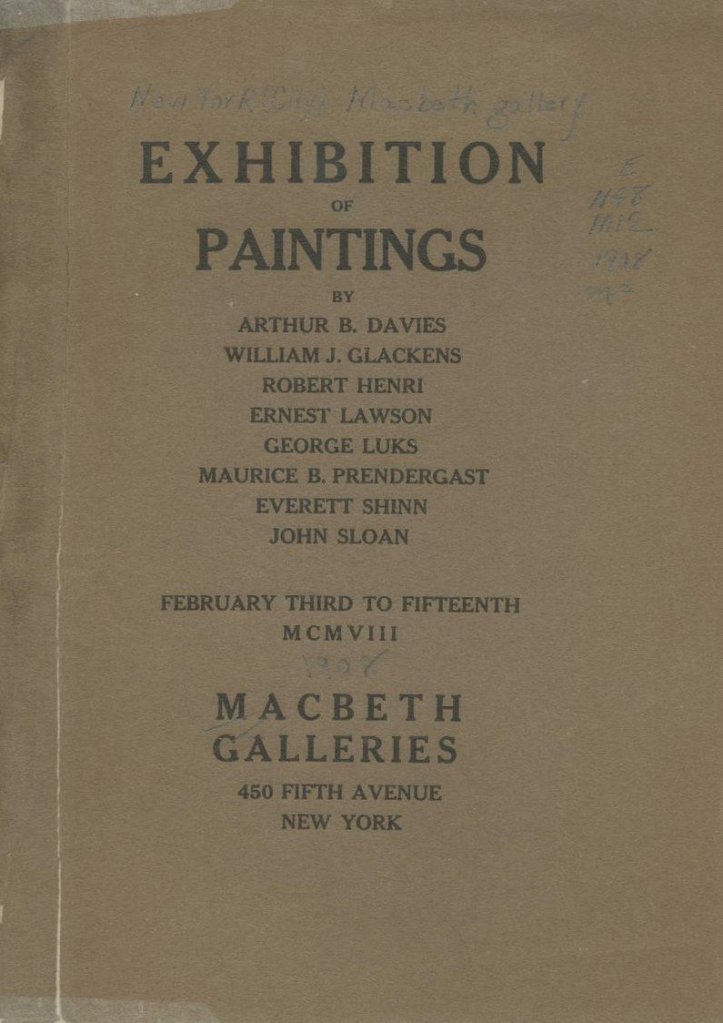

To look at the history of the Ashcan School one has to go back a step and look at a group of painters who became known as The Eight. These eight artists, with Robert Henri, acknowledged as the leader of the group, were Arthur B. Davies, William Glackens, Ernest Lawson, George Luks, Maurice B. Prendergast, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan.

Ashcan School artists and friends at John French Sloan’s Philadelphia Studio, 1898

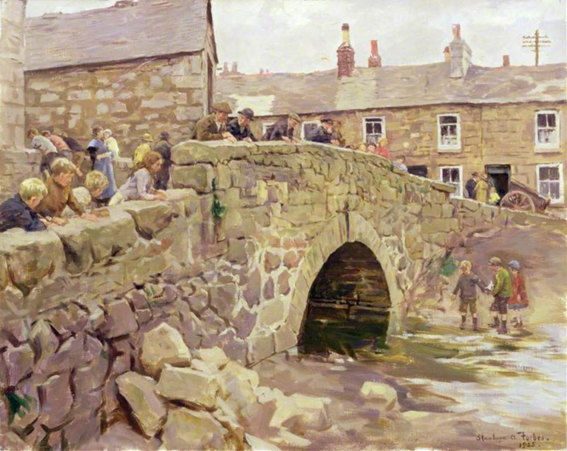

Luks, Sloan, Glackens, and Shinn worked as newspaper artist/reporters and illustrator-cartoonists and maybe because of this connection, the many paintings of these artists took on a journalistic quality. All eight artists utilised the crowded life found on the New York streets as the subject of their paintings. Their work depicted un-idealized views of life in a big city and focused on the bars and the clientele, dark grubby-coloured tenements, pool halls, and slums. This was the epitome of urban realism. Realism in art was described by Gustave Courbet in an open letter he wrote on December 25th 1861, now referred to as his Realist Manifesto. He wrote:

“…To know in order to do, that was my idea. To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my time, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter but a man as well; in short, to create living art – this is my goal…”

At the high point of their popularity these men were seen as confronting Academia which favoured the genteel tradition of “art for art’s sake, and which had dominated the American art establishment for many decades with works from likes of John Singer Sargent and Abbott Handerson Thayer.

However, on February 3rd, 1908, the MacBeth Galleries, New York, opened an exhibition featuring The Eight artists. It caught the attention of the American art world and although the show remained on view in New York for less than a fortnight, it was taken to several cities including Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia. These exhibitions were lauded as watershed exhibitions of 20th-century vanguard art. It was a triumph of “American” art.

The name “Ashcan School” was a derisive criticism of The Eight and their works of art, which appeared in an article in The Masses, an American magazine of socialist politics. The author of the article alleged that there were too many “pictures of ashcans and girls hitching up their skirts on Horatio Street” in their paintings. The group of artists were amused by the article and the group soon became known as the Ashcan School of painters. The Ashcan School of artists had also been known as “The Apostles of Ugliness”.

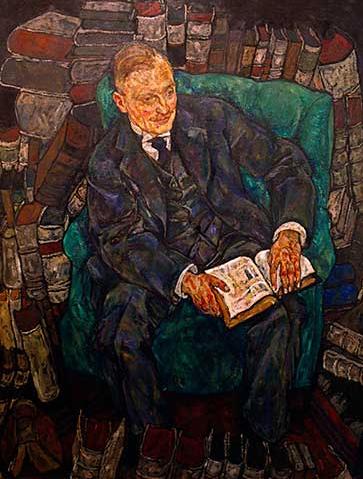

William Glackens by Robert Henri (1904)

A few blogs back I looked at the life of George Luks who was an American realist painter connected to the Ashcan School. Today I am looking at the life and paintings of one of his contemporaries who was also one of the Ashcan School of painters. He is William James Glackens. William Glackens was born in Philadelphia on March 3rd 1870. He was the youngest of three children to Samuel Glackens, a cashier for the Pennsylvania Railroad and his wife Elizabeth Glackens. William’s siblings were an older sister, Ada and an older brother Louis who would later become a cartoonist and illustrator and work on early animation films.

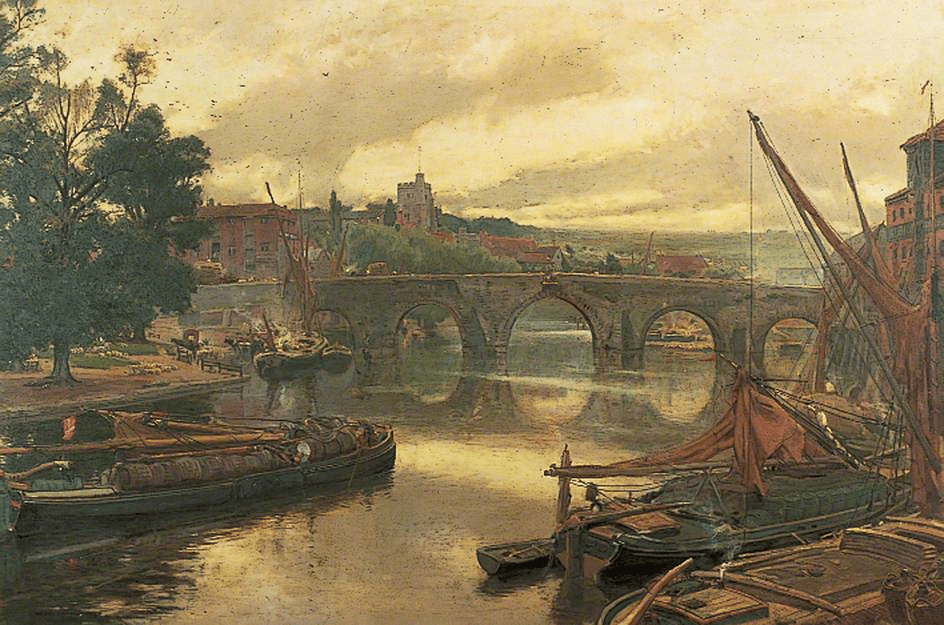

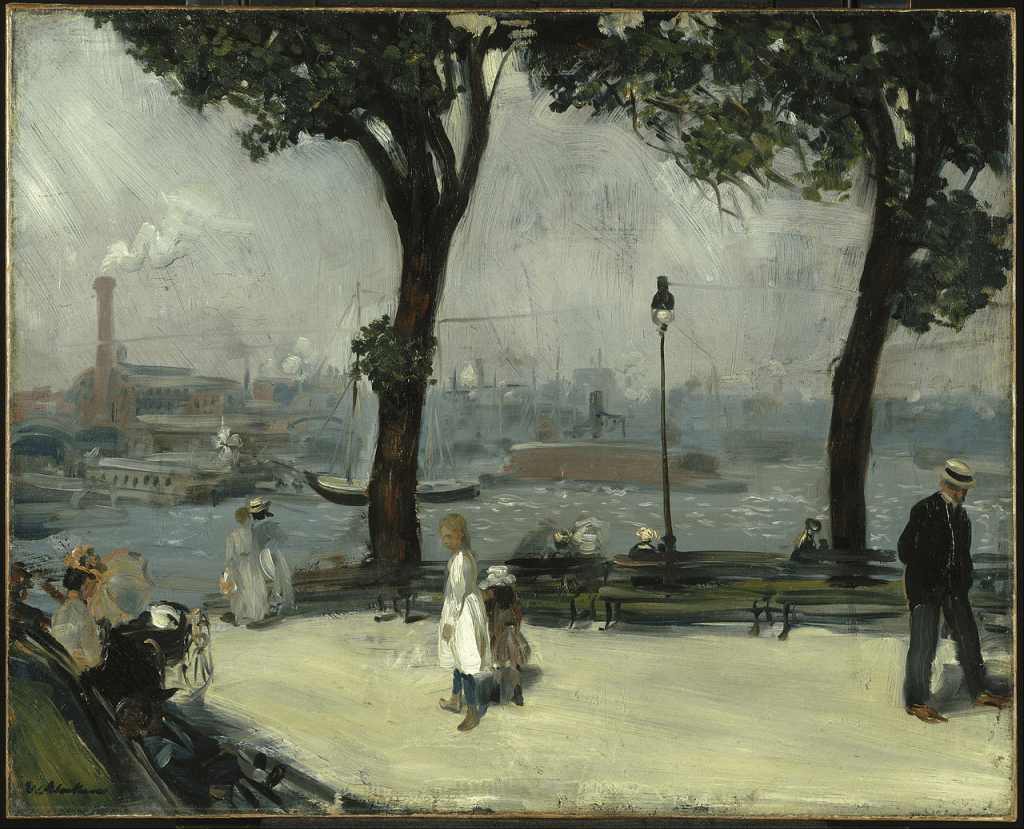

East River Park by William Glackens (1902)

William attended the Central High School where one of his fellow students John Sloan, who would later become a member of The Eight. Glackens graduated from the Central High School in 1890. Throughout his school days Glackens loved to draw and paint and became a very accomplished artist and in November 1891, aged twenty-one, he and Sloan enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. Glackens also worked as an artist reporter for many newspapers, starting at the Philadelphia Record. His task was to pictorially record news events and had to work to tight deadlines.

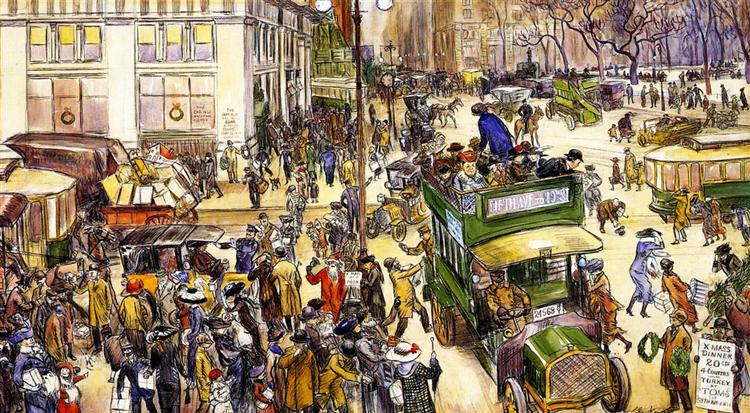

Christmas Shoppers by William Glackens (1912)

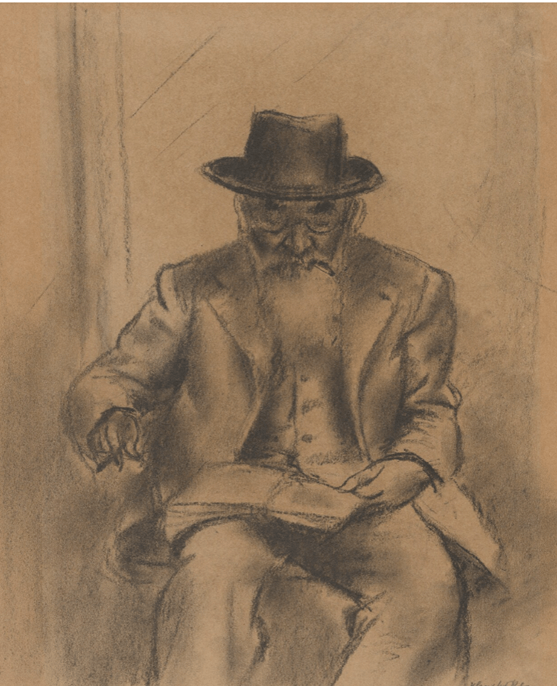

In October 1894, having completed his studies at the Academy of Fine Art, Glackens started a job as a staff artist/reporter for the Philadelphia Press and worked alongside fellow artists Sloan, Edward Davis, George Luks, and Everett Shinn. Around this time Glackens was introduced to Robert Henri by Sloan. Henri was an artist five years older than the pair. He had returned to study at the Academy for a second stint after spending time in Paris studying at the Académie Julian, under William-Adolphe Bouguereau, where he developed a love for Impressionism and later, he was admitted into the École des Beaux Arts. Besides befriending Glackens and Sloan two more aspiring artists, George Luks and Everitt Shinn joined the informal group which met at Henri’s apartment to discuss art, philosophy, culture and more, their meetings became known as the Charcoal Club because they would spend time using that medium to produce drawings from life. This informal group explored art genres not available at the Academy, such as nude figure drawing. They also became interested in the social philosophical writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Émile Zola, and Henry David Thoreau. Besides meeting to draw. paint and discuss philosophy, the group led a very sociable life during which alcohol played its part !

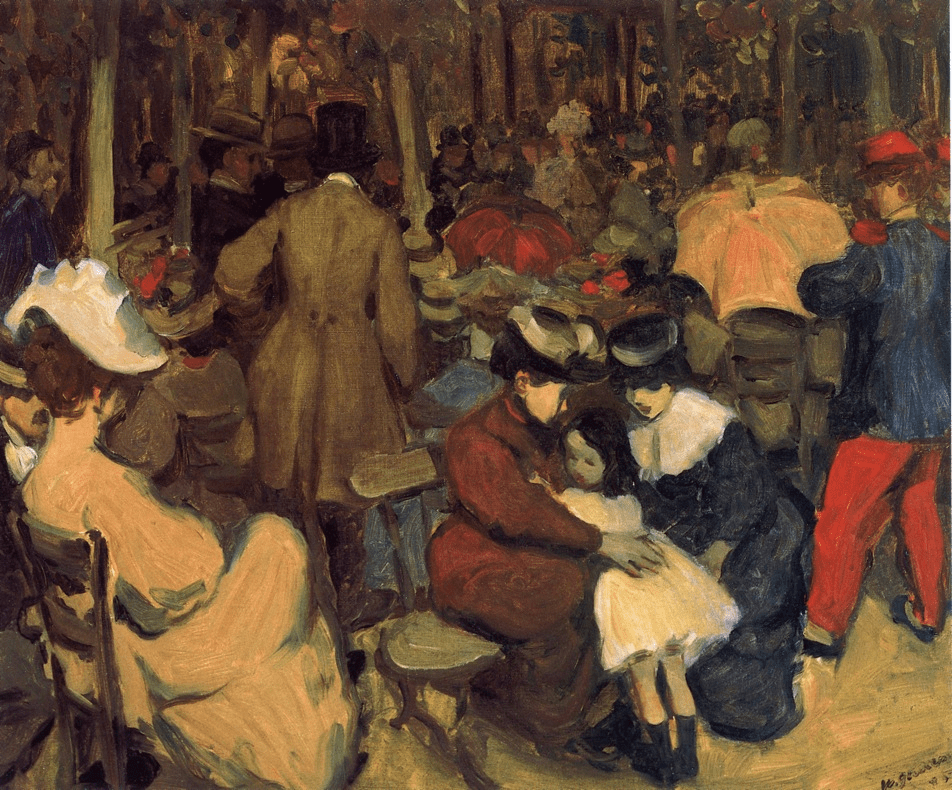

Figures in the Park, Paris by William Glackens (1895)

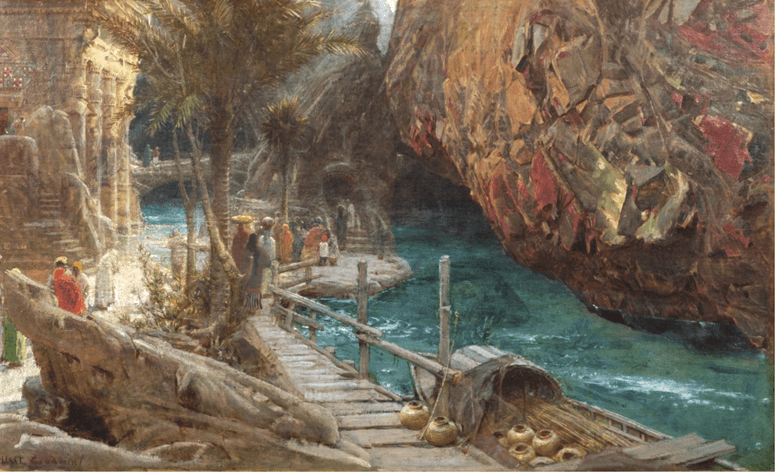

In 1895, Glackens, along with several other artists, including Robert Henri travelled to Europe so that they could learn more about European art. The first country they visited was Holland where Glackens scrutinised the work of the Dutch masters. From there he went on to the French capital where he and Henri rented a studio apartment for a year. For Glackens, staying in Paris, exposed him to the work of the great Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. His greatest influence was the work of Manet.

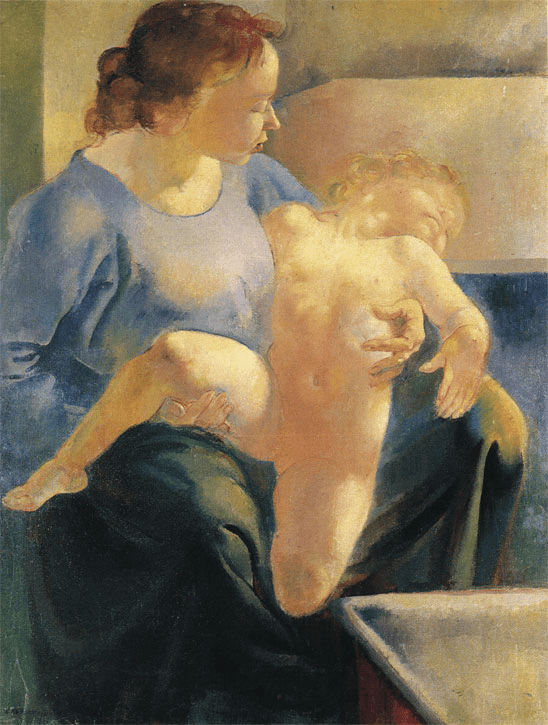

Lena (the artist’s daughter) Painting by William Glackens (1918)

Glackens returned to America in 1896 and moved to New York and spent time at Henri’s many social gatherings. Glackens took up employment at the New York Herald as a reporter and also worked as an illustrator for various magazines. These two lines of work provided him with a good steady income and over the next decade he produced more than a thousand illustrations. Although many were comedic in nature, in April 1898 the Spanish-American War broke out in Cuba and the McClure’s Magazine sent him there to collate the news and produce newsworthy illustrations. It was a difficult assignment and his living conditions were poor. On his return to New York, he was taken ill and it was discovered that he had contracted malaria which would return time and again during his life.

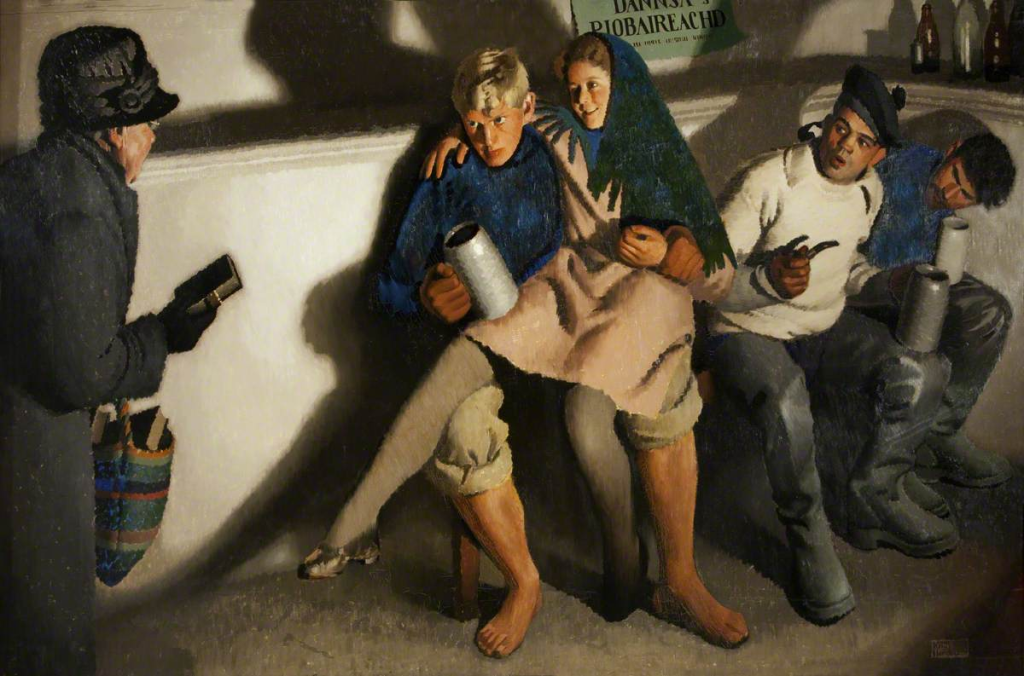

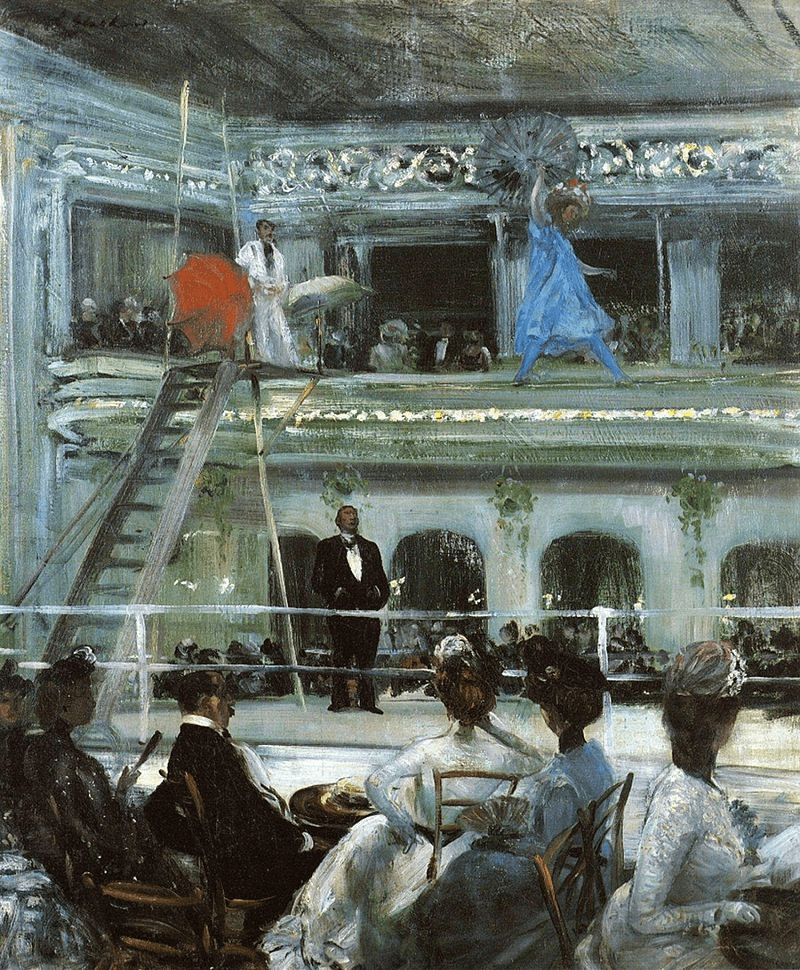

Hammerstein’s Roof Garden by William Glackens (1901)

In 1901 Glackens completed a painting entitled Hammerstein’s Roof Garden. Hammerstein’s Roof Garden was the official name of the fashionable semi-outdoor vaudeville venue that theatre magnate, Oscar Hammerstein I, built atop the Victoria Theatre and the neighbouring Theatre Republic. During summer months theatres were often closed due to the suffocating atmosphere inside the venues and so roof garden venues were very popular. The viewer is placed as if they are part of the audience and in front of us, we see a a colourfully dressed female tightrope walker as she tentatively navigates the rope which is strung across the stage. In the foreground we see the audience, some of which are unaccompanied females which was something that years ago would have been unheard of. The painting is now part of the Whitney Museum of American Art collection in New York.

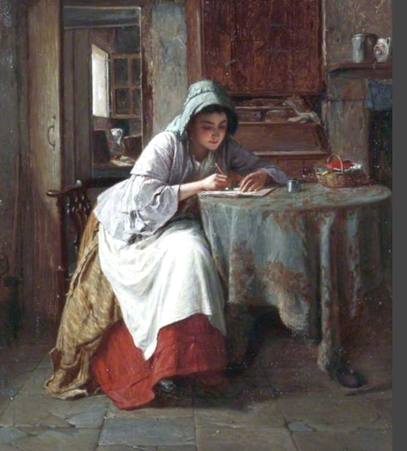

The Artist’s Wife, Edith Dimock Glackens, in her Wedding Dress by William Glackens (1904)

William Glackens’ single status ended in 1904 when he married Edith Dimock. Edith, who was six years younger than William, came from a wealthy Hartford Connecticut family which made its fortune as silk merchants. Despite her family’s strong objections but she turned away from business as a career and instead set about becoming a professional artist. She left home and moved to New York City when, in her early twenties, she enrolled at the Art Students League where she studied with American Impressionist William Merritt Chase.

Sweat Shop Girls in the Country by Edith Dimock (c.1913)

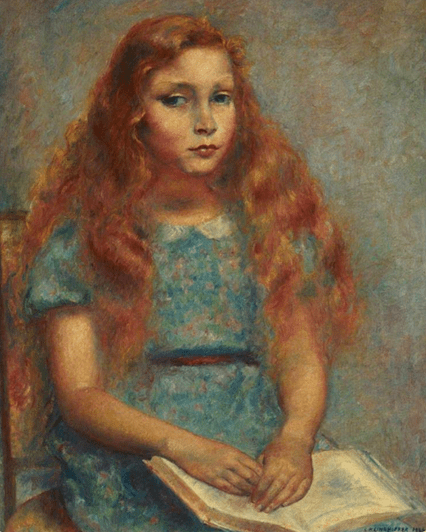

She soon made a name for herself as a talented watercolourist depicting women and children of working- and middle-class backgrounds. Through his wife’s wealth, Glackens could concentrate on his art, and often Edith and later their daughters, Ira and Lenna became his models. His 1901 portrait of his wife is of a classical formal style. Set against a dark background, Edith is depicted wearing a black coat and hat with a long brown pleated skirt. As with many of his portraits Glackens wanted his subjects to be seen just as they were, warts and all, and refused to idealize his sitters. In this portrait Glackens has made no attempt to either make the depiction more modern or beautify the sitter.

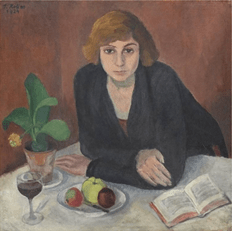

Portrait of Edith Dimock Glackens by Robert Henri (c.1902)

His friend Robert Henri also painted a portrait of Edith around the same time which appears more idealized and certainly adds a touch of beauty to the depiction.

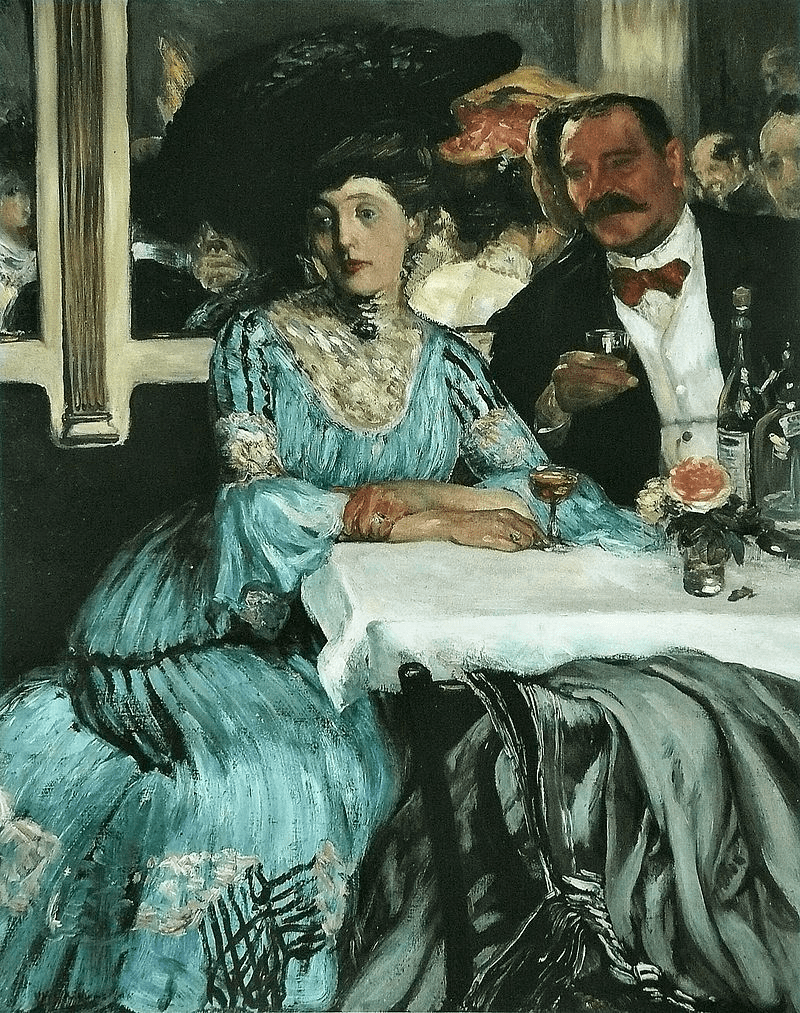

At Mouquin’s by William Glackens (1905)

Artists need to sell their work and to do this their work has to be shown at exhibitions. However it was not always easy for many artists to have their work accepted by exhibition juries and in 1907, Glackens and many of his contemporaries decided to take the matter into their own hands and split from the National Academy of Design who they felt, for some reason, stopped accepting their work The Eight, as they had come to be known, led by Robert Henri decided to host their own exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York City and an opening date for the event was set for February 3rd 1908.

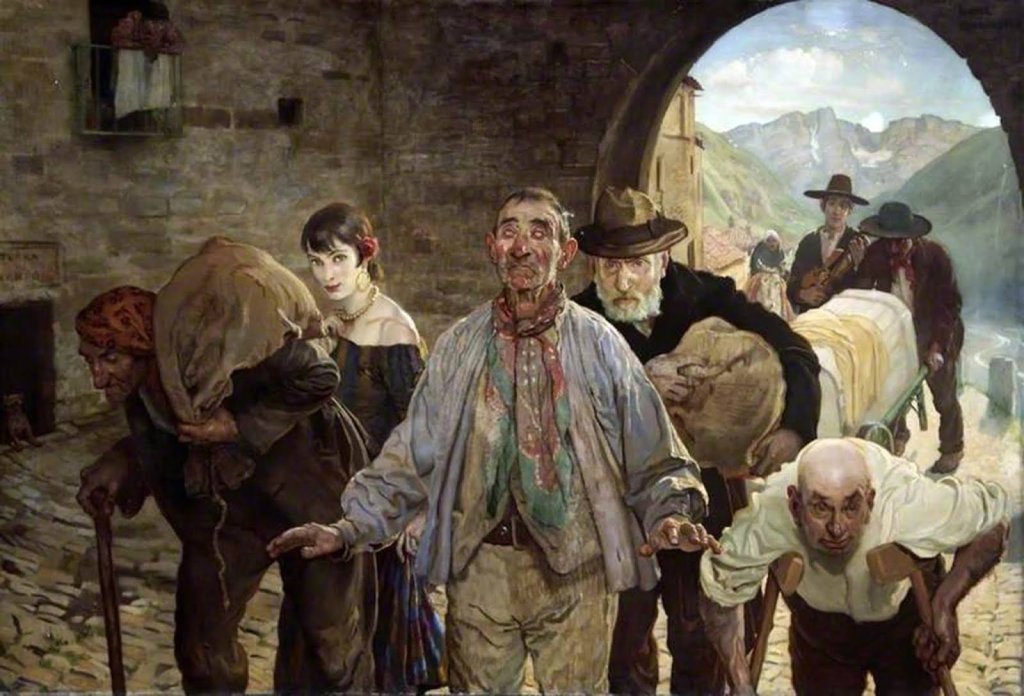

May Day in Central Park by William Glackens (1905)

Although part of the Ashcan School of Painters, Glackens preferred to use a lighter palette for his work, unlike the darker palette used by the others who liked to depict the darker and grittier side of life in the city. For Glackens depictions of family life whilst shopping or relaxing in the park were his favourite subjects for his paintings. Unlike his colleagues Glackens preferred to focus more on scenes of leisure and entertainment rather than concentrate on the misery of life in the slums of the Lower East Side.

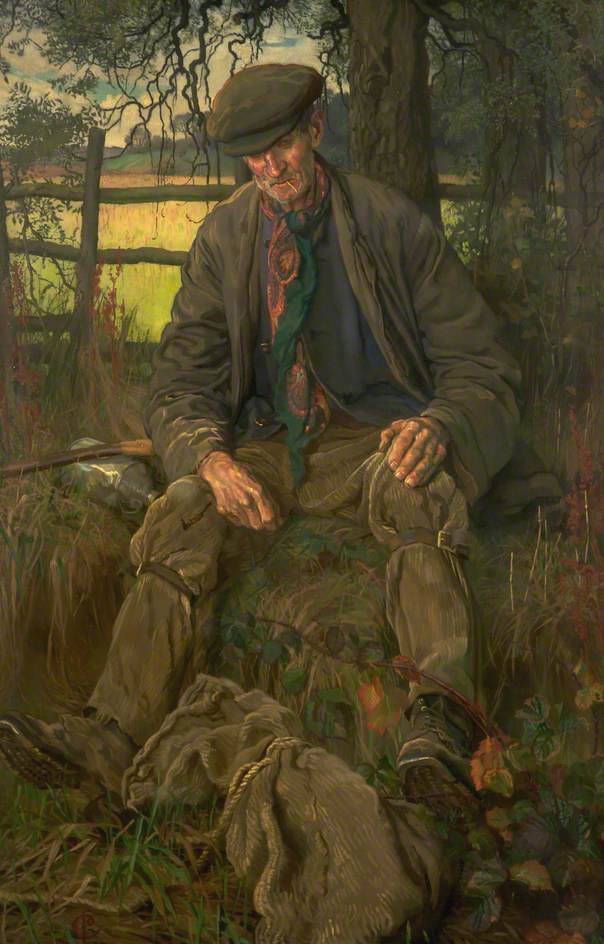

The Green Car by William Glackens (1910)

The consequences of working as an artist/reporter for a number of Philadelphia and New York newspapers taught him to observe the smallest of details of a scene. In New York Glackens had a studio on Washington Square Park and it was from here he captured a scene for his 1910 painting entitled The Green Car. The painting depicts a green trolley car as it rounds the corner at the south side of the park and we see it is heading towards a lady who is standing by the snowy curb, waiting to alight. She is dressed smartly in a long coat, hat, and muff, she signals to the conductor of the trolley car. Our eyes move from the foreground and the green trolley car across the snow-covered grass, through the trees and finally alight on a row of three-storey brick tenement buildings.

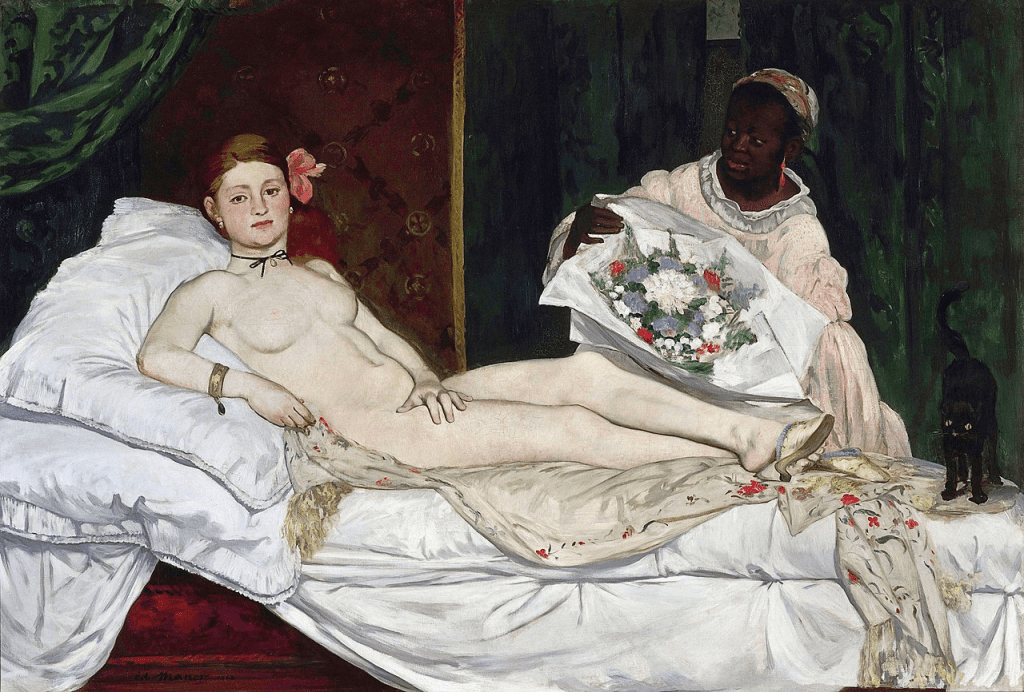

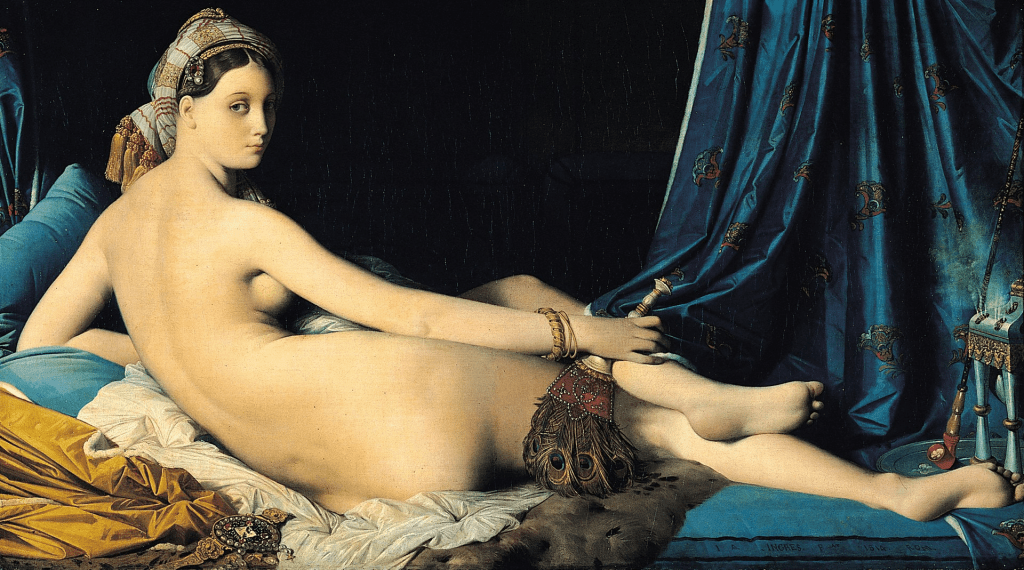

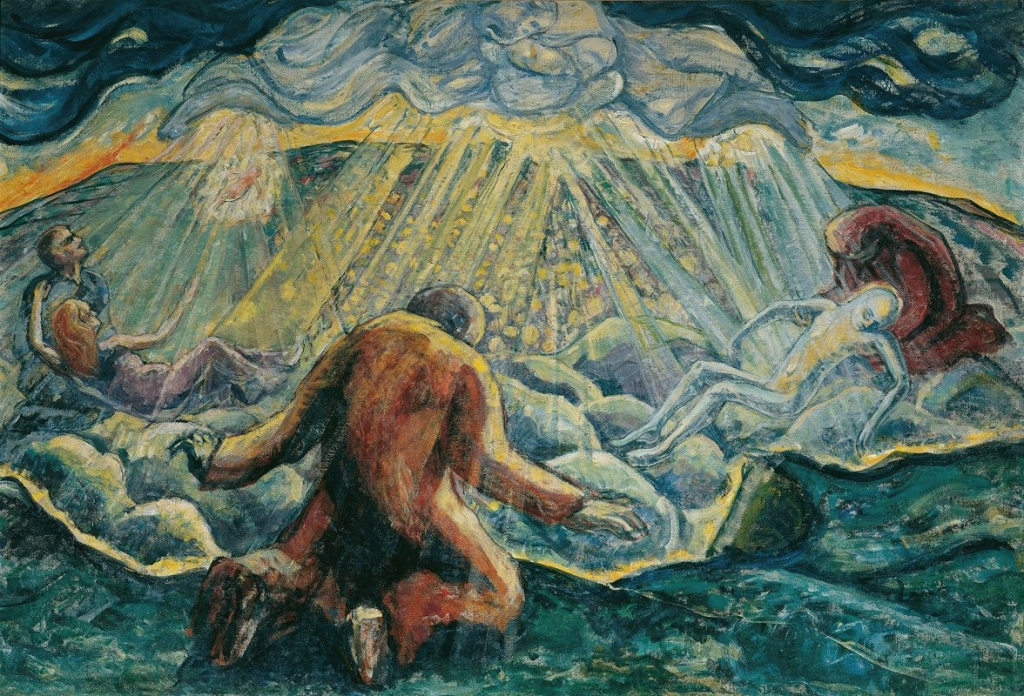

Olympia by Manet (1863)

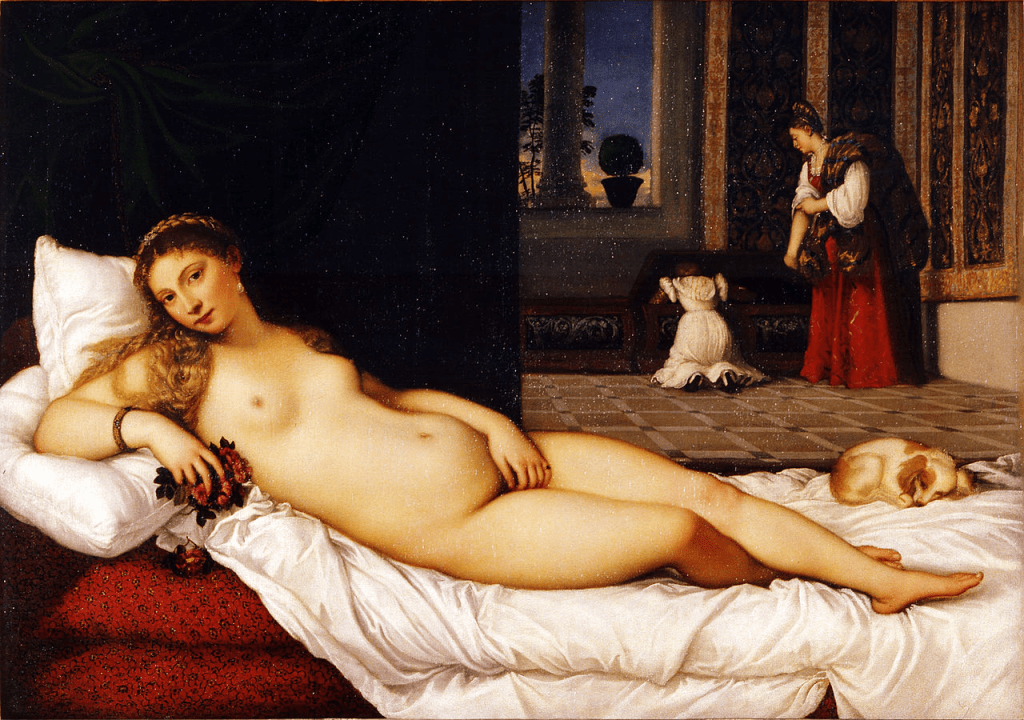

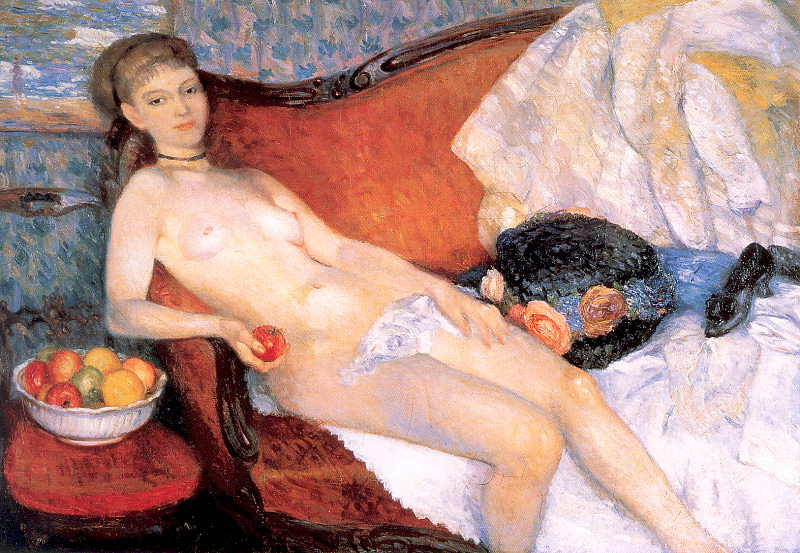

In 1910 Glackens produced what many believe is his homage to Édouard Manet’s Olympia with his painting entitled Nude with Apple.

Nude with Apple by William Glackens (1910)

It depicts a reclining nude holding an apple which she has taken from the nearby bowl on her right. To her left on the sofa there is a large hat and a pile of her discarded clothing including one blue shoe. She wears a black choker around her neck which harks back to the same accoutrement warn by Manet’s reclining nude, Olympia. Whereas Manet’s Olympia covered her pubic region with her hand, Glackens has modestly covered his model’s pubic region with a piece of discarded white lingerie. Glackens’ depiction is another of his typical realist genre. The model is ordinary. She could not be termed beautiful. The depiction alludes to her being simply one of Glackens’ models who has just arrived at his studio wearing a large flowery hat, a gown and blue shoes. She then hurriedly undressed, abandoning her clothes on the sofa. The scene seems to have been unscripted. And yet…..are we to think of the apple in her hand as symbolising Eve?

Breezy Day, Tugboats New York by William Glackens (1910)

Glackens extensive knowledge of European art and artistic trends in Europe led him to be commissioned by Albert Barnes, the American chemist, businessman, art collector, writer, and educator, in January 1912 to travel to Europe and buy paintings for him which would then become the foundation for the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia. Barnes was also a High School classmate of Glackens and gave him twenty thousand dollars to be used for purchasing paintings and Glackens returned with thirty-three works of art. That December Barnes himself travelled to Paris to buy more works of art.

Soda Fountain by William Glackens (1935)

On Feb. 17th, 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art opened at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue in New York. The Armory Show, as it came to be known, had a profound effect on American art. William Glackens helped to organize the American section of this ground-breaking exhibition but later reflected on how the American art was somewhat inferior to the European submissions. He voiced his opinion:

“…Everything worthwhile in our art is due to the influence of French art. We have not yet arrived at a national art […] I am afraid that the American section of this exhibition will seem very tame beside the foreign section. But there is a promise of renaissance in American art…”

William Glackens in his studio (c.1915)

Although he liked the modern and much more abstract European works Glackens maintained his love of painting scenes of everyday life and always remained a realist artist. During the inter-war years Glackens made a number of trips to Europe buying European works to enhance the Barnes collection. Glackens died of a cerebral haemorrhage on May 22nd 1938 while spending a weekend visiting fellow artist Charles Prendergast in Westport, Connecticut. He was 68.