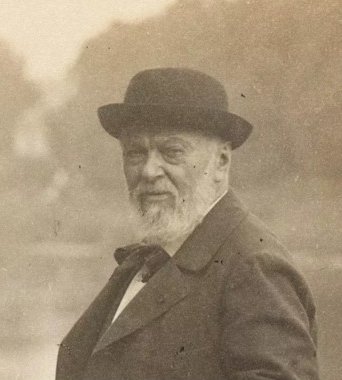

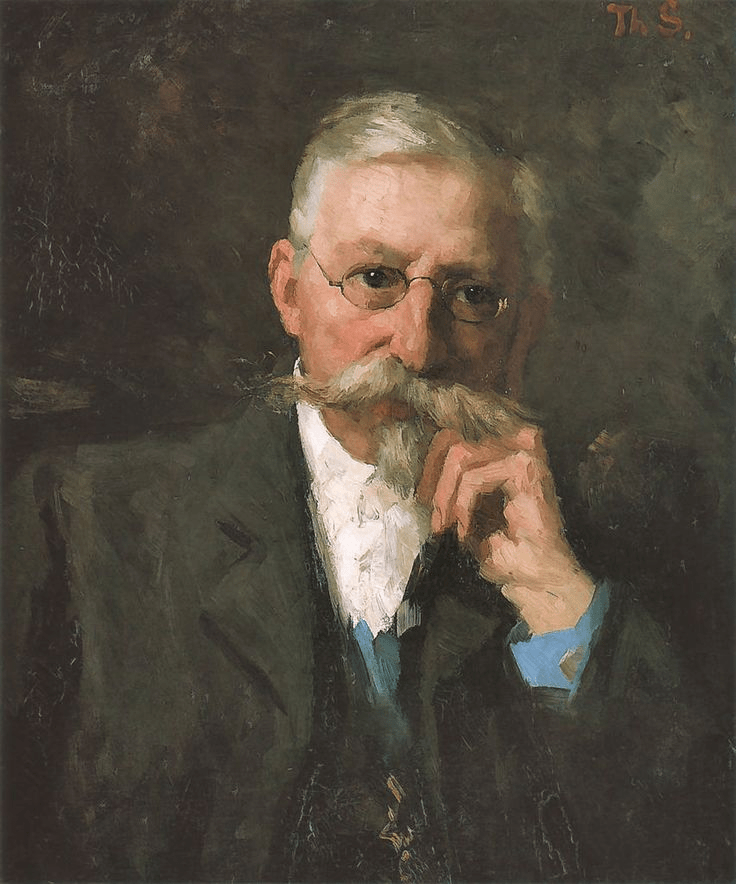

Self portrait by Max Liebermann (1934)

Max Liebermann was Jewish, not a strict Orthodox Jew, but more of a secular Jew who regarded himself through assimilationist eyes. Maybe because of this he avoided painting religious subjects with the exception of a painting he completed in 1879 entitled The 12-Year-Old Jesus in the Temple With the Scholars.

Der zwölfjährige Jesus im Tempel (The Twelve-year-old Jesus in the Temple) by Max Liebermann (1879)

The painting depicts twelve-year-old Jesus in the temple, having been at the Festival of Passover in Jerusalem with his parents, but unbeknown to them, he had stayed behind in the city when they had set off to return home. The story continues as per the biblical tale (Luke 2:43-48):

“…After the festival was over, while his parents were returning home, the boy Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem, but they were unaware of it. Thinking he was in their company, they travelled on for a day. Then they began looking for him among their relatives and friends. When they did not find him, they went back to Jerusalem to look for him. After three days they found him in the temple courts, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions. Everyone who heard him was amazed at his understanding and his answers. When his parents saw him, they were astonished. His mother said to him, “Son, why have you treated us like this? Your father and I have been anxiously searching for you…”

The setting for this painting is derived from Max’s visit to the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam in 1876 when he made architectural sketches of the Portuguese Synagogue of Amsterdam. The curved staircase, which he later depicted as a spiral staircase in the painting, is a reference to the 16th-century Levantine Synagogue in Venice. The paned window on the upper edge of the painting also echoes the windows of the Portuguese Synagogue of Amsterdam.

Liebermann originally depicted Jesus, not as a holy figure, but as a dark-haired boy with Semitic features and mannerisms, arguing the doctrine with his elders. The painting was first exhibited at the First International Art Show in Munich in 1879, at a time when antisemitic activism and propaganda was just starting to break out in Germany. The artwork caused a major outcry with critics terming the depiction blasphemous. The art critic for the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung, Friedrich Pecht, asserted that Liebermann had painted “the ugliest, know-it-all Jewish boy imaginable,” and went on to state that the artist had shown the Jewish elders as “a rabble of the filthiest haggling Jews.” More criticism rained down from upon high with the Crown Prince of Bavaria declaring that he was scandalised, and the Bavarian State Parliament even spent time debating the painting and Pecht’s comments. One Catholic MPs criticised the fact that it had been admitted into a State establishment knowing that the country had inhabitants who were overwhelmingly devout Christians. One deputy pronounced that Liebermann, being a Jew, should have known better than to paint such a scene and that the painting was reviled as “a stench in the nostrils of decent people” It seemed that Lieberman’s mistake was simply that as Liebermann was a Jew, he had depicted an overtly Jewish Jesus.

Preliminary Sketch

And yet in the painting we cannot understand the violent criticism of the detractors regarding Liebermann’s Jesus who is depicted as a long-haired, slightly effeminate, blond boy. However, this was not the original depiction as this is because Liebermann, in response to unrelenting criticism, repainted the figure before it was included in a Paris exhibition in 1884. Art historians know this as a sketch of the untouched 1879 version has been preserved, in which it can be seen that Liebermann had originally depicted a barefoot boy with short, unkempt dark hair and a stereotypical Jewish profile. Liebermann changed the young Jesus’s appearance with the figure once described as an “urchin” now appears as a serious, intelligent, perhaps slightly deferential child. However, the changes, did not change the mood of the German critics and the work was not exhibited again in Germany until the Berlin Secession exhibition of 1907.

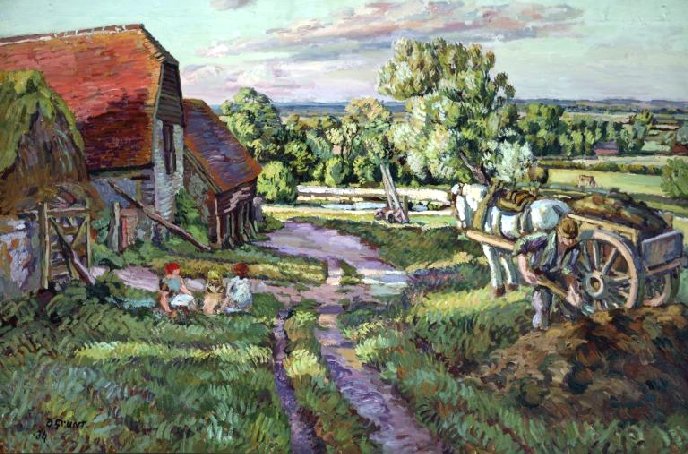

Sewing School by Max Liebermann (1876)

In 1875 Liebermann left Paris and spent three months in Zandvoort in Holland. It was in this Dutch town that Max acquired a brighter and more less planned style by copying paintings by one of his favourite artists, Frans Hals. Max developed a practice of setting aside time between the idea for a motif coming to him and the implementation of the larger finished painting. When he returned to Paris in the autumn of 1875 he moved into a more spacious studio and began to convert his Dutch sketches into full sized works. He returned to the Netherlands in the summer of 1876 where he remained for several months. During this stay he met the etcher William Unger, who brought him into contact with Jozef Israëls and the Hague School. One example of this change of painting style was Liebermann’s work entitled Sewing School which he completed in 1876. The sewing school depicted in this painting was in an orphanage in Amsterdam. Liebermann had started his career as a realist painter, but by the time of this work, he was already establishing himself as an Impressionist-style painter.

Schusterwerkstatt (Cobbler’s Workshop) by Max Liebermann (1881)

During his visit to the Netherlands in the summer of 1880, Liebermann travelled to the small village of Dongen in North Brabant, in the southern Netherlands. It was here that he made a number of studies that would be used when completing the work in his studio. One example of this was his depiction of a cobbler in his workshop. At the workshop, he created studies that he later used for his 1881 painting Schusterwerkstatt, (Cobbler’s Workshop).

Altmännerhaus (Old Men’s Home) in Amsterdam by Max Liebermann (1881)

Having completed the Cobbler’s Workshop painting he travelled to Amsterdam on his way to returning to Munich. It was whilst in Amsterdam that he came across the Catholic Altmännerhaus (Old Men’s Home). He happened to glance into the garden of the establishment and saw a large group of older gentlemen dressed in black sitting on benches in the dappled sunlight. According to Erich Hancke’s 1914 book, Max Liebermann. Sein Leben und seine Werke:

“…He [Liebermann] had visited a friend at the Rembrandt Hotel, and when he looked out of the corridor window descending the stairs, his gaze fell down into a garden where many old men dressed in black were standing and sitting in a corridor bathed in sunlight […]. He later used a drastic analogy to characterize that moment: ‘It was as if someone were walking on a level path and suddenly stepped on a spiral spring that shot him up…”

Study for Old Men’s Home in Amsterdamby Max Liebermann (1881)

Liebermann immediately began to paint the scene and concentrated on the effect of light which was being filtered through a canopy of leaves and this dappled effect became known as “Liebermann’s sunspots” and would be seen in Liebermann’s later Impressionist depictions. He made two on-site portrait-format studies of the scene, one in oil and one in pastel, after which Liebermann painted the final picture in his Munich studio later that year. The painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon and received an honourable mention. Furthermore, Léon Maître, a well-known collector of Impressionism, acquired several of Liebermann’s paintings.

Recreation Time in the Amsterdam Orphanage by Max Liebermann (1884)

Life in Paris was taking its toll on Liebermann. He needed to sell his artwork to prove to himself and his parents that he had not wasted his life. This continual pressure caused Lieberman to fall into periods of deep depression and his painting output declined, furthermore, the works he put into the Paris Salon were not getting the recognition he believed he had deserved. There was also still the anti-Prussian sentiment amongst the French and this did not help him sell his work. In all, he realised that the Netherlands or Germany were much more acceptable places to work and live. He left Paris and spent a couple of months in Venice before returning to Munich in 1878. It was here that he was able to enhance his status as an important progressive artist. Munich had everything Liebermann required – the artistic culture and patrons who supported him. He spent hours visiting the city’s museums and art galleries and creating everlasting and important friendships. He eventually left Munich and relocated to Berlin, his birthplace, in 1884, where he remained for the rest of his life.

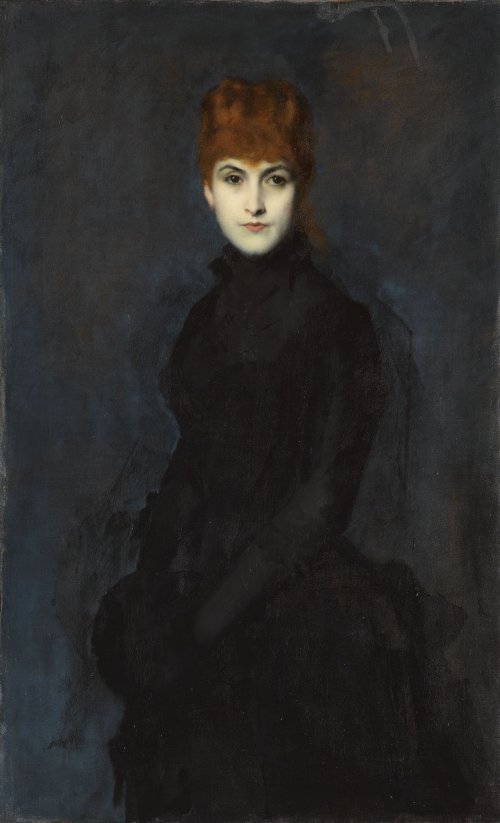

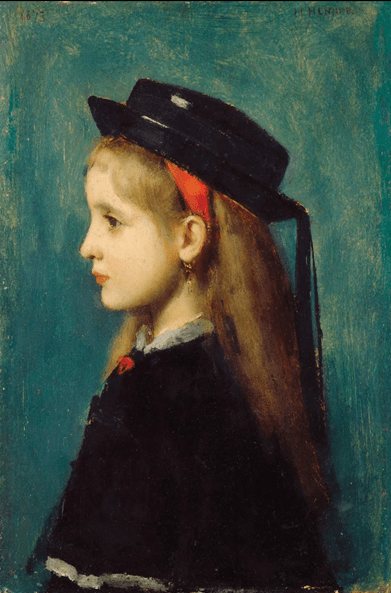

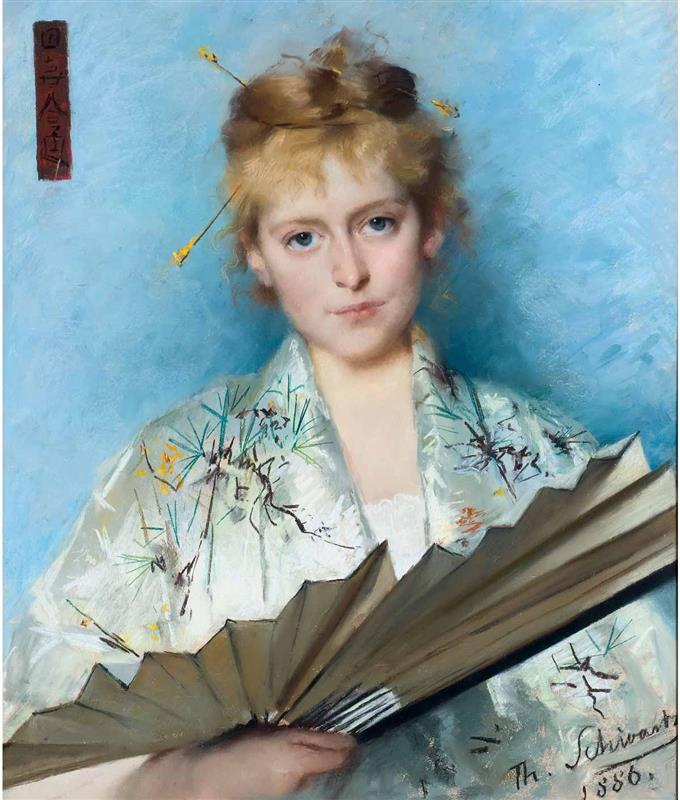

Martha Marckwald by Anders Zorn (1896)

In that same year, 1884, that Max moved to Berlin he married Martha Marckwald, the fourth child of the German Jewish couple Ottilie and Heinrich Benjamin Marckwald, who ran a wool store in Berlin. When Martha’s father died in 1870, Max’s father Louis became the thirteen-year-old Martha’s guardian. The Marckwald and Liebermann families became even closer when Max’s elder brother Georg Liebermann married Martha’s elder sister Elsbeth. On September 14th 1884, thirty-seven-year-old Max Liebermann married twenty-six-year-old Martha. It was a marriage that would last more than fifty years until Max died in 1935. In August 1885 Max and Martha’s only child, Käthe, was born and in 1892.

Max’s mother died on August 12th 1892, aged 70 and his father died two years later on April 29th 1894, aged 75. Although the death of his parents was a sad time for Max, he was finally released from their unrelenting words of warning as to the perilous status of an artist. Max moved into his family’s Berlin home in Pariser Platz where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Liebermann Villa at Wannsee

In 1909, overwhelmed by the noisy life in the German city, the Liebermann family bought a plot of land in the Alsen summer villa colony on the northern shore of the Kleiner and western shore of the Großer Wannsee at Wannsee, some twenty kms south-west of Berlin, close to Potsdam. It was here that they built themselves a summer home, somewhere to retire to during the hot summer months when city life became very oppressive. The Villa was designed by the architect Paul Otto Baumgarten, the garden by Liebermann in collaboration with the then-director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Alfred Lichtwark.

Martha Liebermann in the garden at Wannsee

Their summer home was situated amidst the magnificent villas of this impressive Berlin colony, embedded in a park, and represented a unique cultural landscape of the time of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic.

The Villa at Wannsee by Max Liebermann (1930)

Flowering Shrubs by the Gardner’s Cottage by Max Liebermann (1928)

The Flower Terrace at Wannsee by Max Liebermann (1915)

During the following years, Liebermann had designed a beautiful garden at the Villa Wannsee. He was so proud of the finishing results that the garden became the subject of many of Liebermann’s painting.

The Artist in His Studio by Max Liebermann (1932)

During the latter decade of the nineteenth century Liebermann continued living and painting in Berlin and would spend his summers at Wannsee or the Netherlands. Liebermann, like many of his contemporary Berlin artists, were dissatisfied with how they were being treated by the Association of Berlin Artists and the restrictions on contemporary art imposed by Kaiser Wilhelm II, so sixty-five of them seceded as a demonstration against the standards set by the Association and the government endorsed art. This break-away became known as the Berlin Secession and its aim was to form a “free association for the organization of artistic exhibitions”. In 1898, Liebermann became the President of the Berlin Secession, which was simply a group of artists that was formed as an alternative to the conservative arts establishment.

Two Riders on the Beach by Max Liebermann (1901)

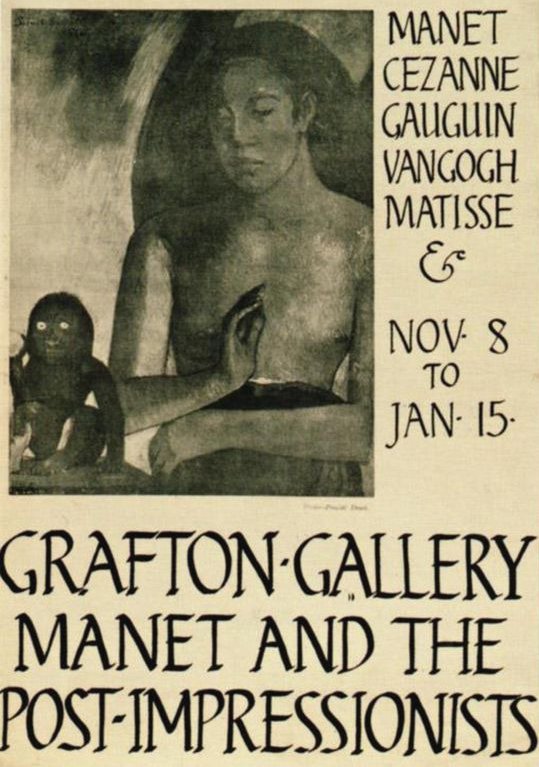

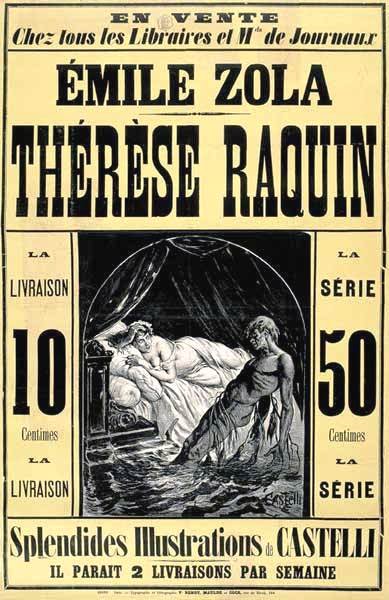

The Berlin Secession championed new forms of modern art and were not be tied down to and be dominated by the old-fashioned academic art favoured by the Berlin Academy. These break-away groups from the art establishments were not new occurrences as the same happened with the Munich Secession in 1892 and the Vienna Secession in 1897. The initial breakaway took place in Paris in 1890 when the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts along with its exhibition arm, the Salon au Champs-de-Mars, was formed as a modern alternative to the official Société des Artistes Français and its exhibition arm, the Salon de Champs-Élysées. These break-away groups all wanted the same thing – the rejection of the official arts governing bodies due to their aversion of avant-garde art such as Impressionism, forms of Post-Impressionist painting and Naturalism, as well as their obstructive exhibition policies, which were inclined to support time-honoured painters and sculptors over their younger, more modernist contemporaries.

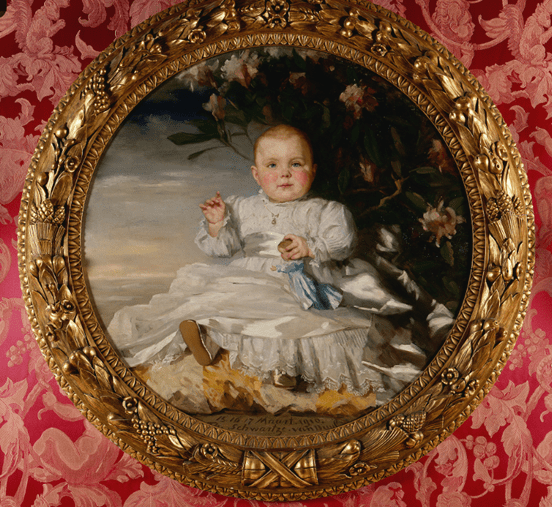

Marthe Liebermann with her grand-daughter Maria by Max Liebermann (1922)

In 1920, Liebermann became president of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, which was the highpoint of his career and signified how the Academy had changed over since the time of the Berlin Secession.

Portrait of President Paul von Hindenburg by Max Liebermann (1927)

Being a Jew, Liebermann had got used to the anti-Semitism in his homeland but by the early 30s with the rise and coming to power of the National Socialists it had noticeably worsened. In a way, it was a good thing that Liebermann died quietly in his sleep at the family home on February 8th 1935 aged 87 as he avoided bearing witness to the atrocities which followed. In 1938, his daughter Käthe her husband Kurt Riezler and their twenty-one-year-old daughter Maria were forced to flee the country and go to America.

The Graves of Max and Martha Liebermann at the Senerfelderplatz Jewish Cemetery, Berlin

They tried to persuade Max’s widow, Martha, to also emigrate but she refused to leave the land where her husband was buried. Martha Liebermann remained in Berlin, ultimately committing suicide in 1943 to escape her impending deportation to a concentration camp.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent website Liebermann Villa am Wannsee which goes into detail about his life and works.

I also consulted the informative website on all things art: The Art Story

Information regarding the painting, A Twelve-Year-Old Jewish Boy, came from the website: Art and Faith Matter/s