The featured artist in My Daily Art Display blog today is the much loved French post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin. This is the first time I have featured a painting by the artist which I am sure is very remiss of me. I have spent a great deal of time researching Gaugin’s life. There are numerous books and articles about his life and what I found strange is that they don’t all agree on some of the lesser known facts. I have tried to bring together the masses of information I have discovered about the great man and I have made an informed guess as to which is the true version of some of the things that happened to him. My collated version of his life is a little too long to put into one blog so over the next few weeks I will serialise the fascinating tale of his life and on each occasion include one of his major works. So let me start at the beginning…………………………

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin was born in Paris in June 1848. His father, Pierre Guillaume Clovis Gaugin was a radical French journalist working as an editor for the liberal-leaning, anti-Bonapartist National newspaper. His mother was Aline Maria Chazal, who was half French and half Peruvian Creole and who like her husband had strong political convictions. Paul Gaugin was the youngest of the couple’s two children, and their only son. Gaugin’s maternal grandmother, who lived in Peru, was Flora Tristan. She was the daughter of a Peruvian nobleman, and came from a very powerful and wealthy Peruvian dynasty. She was a socialist writer and activist and also one of the founders of modern feminism.

In 1848 Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte came to power which caused a great deal of political unrest. It ended in a coup d’état and revolution in 1851 and the dissolution of the French Assembly along with the imposition of Napoleon III on his people. Gaugin’s father held strong political against Napoleon III and he frequently expressed such opinions in newspaper articles. In August 1849 because of the political turmoil, he and his family fled Paris and headed for Peru with the idea of setting up a newspaper in Lima. Gaugin’s father, Clovis, suffered a sudden heart attack during the voyage and died, aged 35, leaving Paul, his mother and sister Marie to fend for themselves. They lived for four years in Lima with Paul’s great-uncle and his family. Gaugin’s mother sought protection and help for her family from the powerful and wealthy Don Pio Tristan Moscoso, the head of their extended family, who had family connections with the president of the country.

Despite the Gaguins sharing the exclusive and wealthy lifestyle of the Moscosos in Lima, when an opportunity arose to return home to France at the end of 1854, Aline seized it. She was well aware that her presidential cousin was losing political power and that Don Pio’s promises to leave her a comfortable legacy might come to nothing. Gaugin’s mother Aline decided that her best opportunities of an independent life lay in Europe. Around this time she had also received word that her late husband’s father, Guilliame Gaugin, a retired merchant and widower, who was close to death, wanted to make his only grandchildren, Paul and Marie, his heirs. Aline Gaugin realised that her future and that of her family now lay not in Peru but back in France.

In 1855 Aline, Marie and Paul Gaugin returned to Orléans, and went to live with their paternal grandfather. While living there Paul and Marie attend an Orléans boarding school as day students. Their grandfather Guillaume died within months of their return to France, and it was also around this time that Aline’s great-uncle, Don Pio de Tristan Moscoso, died in Peru. In 1859, Paul Gauguin enrols in the Petit Séminaire de la Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, which was one of the top boarding schools located a few miles outside of Orléans, where he completed his education over the next three years. His mother leaves Orléans and moves to Paris, and her children live with her there while on school breaks. With the money she has received in her father-in-law’s will and because she was a trained dressmaker, she opens her own dressmaking business on the rue de la Chaussée in Paris in 1861. Aline Gaugin falls ill in 1865 and retires to the Parisian countryside of St Cloud, a western suburb of Paris. It is whilst living here that she meets and is befriended by a Parisian financier, Gustave Arosa, a wealthy Jewish businessman of Spanish descent who has his summer residence near to her home.

After his spell at the boarding school in Orléans, Paul Gaugin attends the Loriol private school in Paris where he prepares for the very demanding École Navale’s entrance examination. It is probably at this juncture in Gaugin’s life that he receives his first artistic training as part of the exam is to be able to draw from plaster casts and live models as well as technical drawing and map making. He doesn’t succeed in the exams but in December 1865, aged 17, Gaugin is accepted as a pilotin (officer cadet) in the merchant marine and his first positioni is on the vessel Luzitano which plied its trade between Le Havre and South America and Martinique. He eventually reaches the rank of second lieutenant at the age of eighteen. His mother Aline dies in July 1867 aged 42 whilst her son is away and in her will she entrusts Paul Gaugin and his sister Marie to the guardianship of Gustave Arosa. Gaugin’s arrives back in Le Havre in December 1867 and he leaves the ship. In January 1868, Gauguin joins the French navy to fulfil his military service requirement and in that March becomes a sailor third-class aboard the vessel, Jérôme-Napoléon in Cherbourg. At the start of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870, Gaugin serves in the French Naval campaigns in the Mediterranean and North Sea.

In April 1871 Gauguin completes his military service and returns to his late mother’s home in St Cloud, only to find it has been destroyed during the Franco-Prussian War. He then moves back to Paris and takes an apartment near to where his former guardian Gustave Arosa lives with his family.

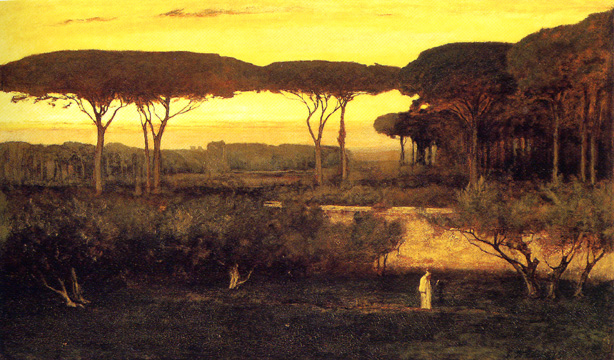

I will leave Gaugin’s life story at this point in time, 1871, and look at My Daily Art Display’s featured painting which Gaugin completed in 1888. It is entitled La Vision après le Sermon (La Lutte de Jacob avec l’Ange) [The Vision After the Sermon (Jacob wrestling with the Angel]. It can now be found in Edinburgh, hanging in the National Gallery of Scotland which purchased the painting in 1925 for a mere £1150. The depiction of Jacob battling the angel had been depicted in paintings and murals before. Rembrandt painted the scene in 1659 and Eugène Delacroix painted a mural of the scene in 1861 which can be seen in the Church of St-Sulpice in Paris, which of course has received thousands of visitors since the church was featured in the book The Da Vinci Code. Works of art concerning the subject were also painted by Gustave Doré in 1855 and Gustave Moreau in 1878. The latter two could well have been seen by Gaugin.

The painting before us by Gauguin has no identifiable light source and it is dominated by heavily-outlined flat areas of pure and contrasting colours. The perspective Gaugin uses is sharp and by doing this he forces us to look at the paintings background and Jacob’s tussle with the angel. The grass instead of being green is red.

A tree lying across the painting, bottom right to top left creates a strong diagonal as it dissects the painting, separating the real world from the imaginary one. At the time of this painting France was being flooded with all things Japanese and it is thought that the way the tree dissects the painting in Gaugin’s work is something he may have seen in the woodblock print of The Plum Garden in Kameido by the Japanese artist Ando Hiroshige. To the left of the tree we see a solitary cow and a group of Breton women wearing their traditional headdresses. Each design of headdress denotes the ladies class, marital status, standing in society as well as which part of the area the woman comes from. The women have emerged from a church service and on the far right of the painting is the priest who has just delivered the sermon. On the other side of the tree we have the imaginary world created in the minds of the people after hearing the priest’s sermon about Jacob’s struggle with the Angel.

Here we see Jacob wrestling the angel and it is thought that Gaugin’s portrayal of the pair wrestling could have been based on one of the Japanese artist, Katsushika Hokusai’s prints of sumo wrestlers in his 1888 publication The Manga. The story of Jacob and the Angel comes from the Book of Genesis, Chapter 32, in which we are told that Jacob is frantically trying to prove to the angel that he has repented for his sins and will not allow the Angel to leave until he has been successful.

This painting is all about what Gaugin believes the women will be thinking on leaving the church after hearing the priest’s sermon. Gaugin loved the simple faith of the peasants and their spiritualism. He believed that art should be about the inner meaning of the subjects, and not necessarily about their obvious outward appearance. He explains his thoughts about this painting in a letter he wrote to Vincent van Gogh in September 1888.

“…I have just painted a religious picture, very clumsily; but it interested me and I like it. I wanted to give it to the church of Pont-Aven. Naturally they don’t want it. A group of Breton women are praying, their costumes a very intense black. The bonnets a very luminous yellowy-white….. An apple tree cuts across the canvas, dark purple with its foliage drawn in masses like emerald green clouds with greenish yellow chinks of sunlight. The ground (pure vermilion). In the church it darkens and becomes a browny red. The angel is dressed in violent ultramarine blue and Jacob in bottle green. The angel’s wings pure chrome yellow. The angel’s hair chrome and the feet flesh orange…”

Gaugin offered the painting to the local curé of the church in Nizon, Pont Aven but he was horrified by the depicted scene and declined the offering!